Sep 16, 2019 Restaurants

Metro editor Henry Oliver finds cultural nourishment and soulful food from Monique Fiso’s Hiakai Hangi in Wellington.

Monique Fiso is New Zealand’s most important chef. There may be chefs with more restaurants, more revenue, more Instagram followers, more TV shows, more cookbooks, more Michelin stars on their résumé, or more appearances on the World’s Top 50 Restaurants, but, right now, there is no one else doing what she is with, and for, New Zealand food.

In less than a year, Fiso has opened Hiakai (her first restaurant), appeared on Netflix’s The Final Table, and in late August, had Hiakai named by Time magazine as one of the 100 World’s Greatest Places 2019. In doing so, she’s helped bring renewed attention to the potential for New Zealand’s indigenous ingredients and traditional Maori and Pacific cooking techniques.

Before opening Hiakai, Fiso spent two years developing her technical, detail-obsessed take on modern Maori cuisine at pop-ups around New Zealand, usually involving a hangi. But that’s hard to do four nights a week in a suburban fine-dining restaurant in Wellington. Yet in August, as part of Wellington on a Plate, Fiso once again dug a hole in the earth, filled it with 40kg of goat, 30kg of potatoes and a large tray of vegetables, and cooked the second of what she hopes will be an annual event — the Hiakai Hangi.

This year, Fiso roped in three women chefs from around the world: Nyesha Arrington from Los Angeles, whose food is inspired by her Korean and African-American heritage; Ash Heeger from South Africa, who also appeared on The Final Table alongside Fiso and has her own fine-dining restaurant in Cape Town; and Analiese Gregory, a New Zealander who has cooked in some of Europe’s most prestigious restaurants and now leads the kitchen at Franklin in Hobart (“Kind of a traitor to our nation,” Fiso joked as she introduced the chefs).

On a cold, clear Sunday afternoon, we arrived on the lawn of The Lodge, a former officers’ mess hall in Shelly Bay. We stood on the grass, wrapped in coats and scarves, drinking wines from Tohu — the first Maori-owned winery. We were served Heeger’s smoked beef pani puri and Fiso’s raw, dry-aged kingfish with horseradish and pickled pikopiko. At small stations, heated by glowing briquettes, Arrington served warmed oysters with a sauce of butter, fern, seaweed and chives, and Gregory served barbecue skewers of thinly sliced paua and bacon.

When the snacks were gone, the chefs followed. The coldest of us gathered around the abandoned stoves, drinking more wine and warming our hands as the afternoon approached evening and the cool air became sharp. The four chefs re-emerged, wearing headsets and holding spades. As they began to dig out the hangi, Fiso introduced the chefs and then narrated the dig, cheering them on and giving them shit in equal measure as she worked. As some chefs tired, sous chefs stepped in. Then a guest. The earth started steaming. Then the canvas appeared, carefully pulled off to avoid getting dirt in the food. Soon, wire baskets filled with foil-wrapped packages were being lifted from the ground.

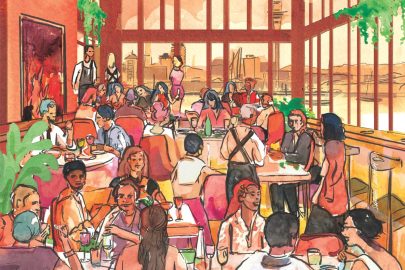

As the chefs took it inside, we followed, taking our seats to be welcomed by the mana whenua and then the Wellington High School kapa haka group. At large round tables, we were served rewena bread with a smoky butter, with bottles of chardonnay and pinot noir placed on the table for self-service.

Then the food from the earth began arriving, served family-style in big, deep bowls. Fiso’s goat leg, stringy and soft, topped with a watercress gremolata; smoky potatoes, still barely firm, covered in seaweed butter; Heeger’s chakalaka (a lightly spicy, acidic relish of peppers and tomatoes topped with parsley and fennel); pumpkin and lentils with a fistful of fresh goat curd; thickly sliced red kumara with a deep-red, sharply spiced roasted tomato and horopito sauce; and, my favourite dish, the cabbage with a titi (muttonbird) XO sauce — smoky, salty, sweet and deeply, soulfully satisfying. We finished with a hangi pudding cake with tamarillo, honeyed ricotta ice cream and coconut shortbread.

The chefs came out to talk and receive applause — four women who gathered in Wellington from different countries, different backgrounds, different cuisines, all led by a Maori-Samoan woman, taking the food and techniques that come from deep in Aotearoa’s past and bringing them into the present, making them anew. This is what food can be that almost nothing else can, I thought as Fiso stood there cracking up the room with her wry humour. A way to not only experience cultures, but to feed off them and literally grow from the interaction. Food not just as culture, but as cultural nourishment.

The writer was a guest of Wellington on a Plate.

This piece originally appeared in the September-October 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline “Feeding off the past”.

Follow Metro on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and sign up to our weekly email