Dec 5, 2021 Food

I would like to think my brother and I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for kaimoana. As Mum tells it, when she met Dad, he had his underpants on his head collecting pipi at Maraetai Beach. Dad doesn’t remember whether he invited this skinny blonde girl to join him for kai or she just sat down and helped herself, but the story of their meeting is the first of many that involve food.

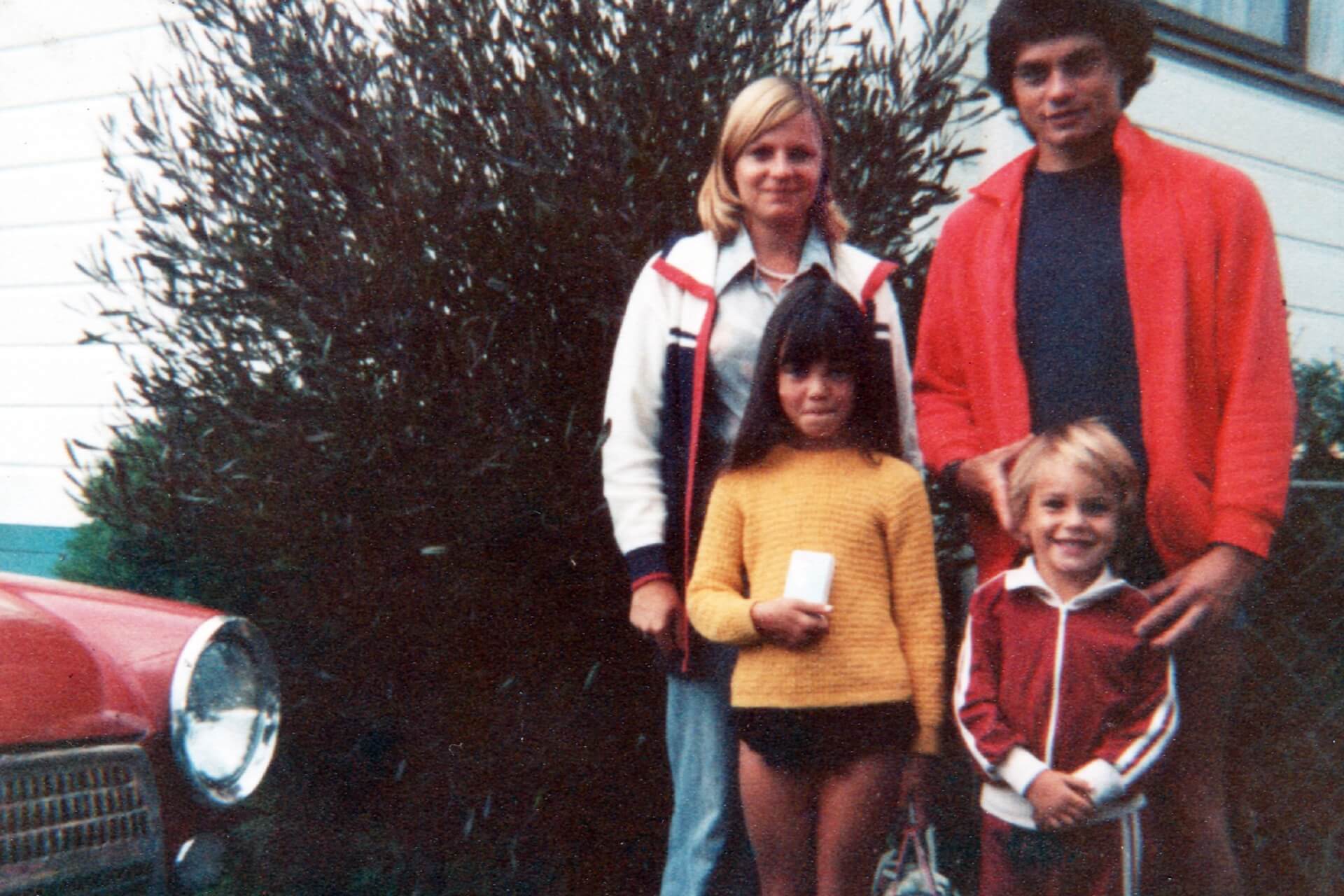

We grew up in Papakura in the 1980s and 90s in a brand-new subdivision that was slowly eating its way into South Auckland farmland. Mum and Dad planted a massive garden with every herb, vegetable, fruit and citrus tree imaginable. We could only pick the neighbour’s passionfruit once they started growing over our side of the fence, but otherwise our parents showed us there were no boundaries when it came to food.

In the mornings before school, my brother and I would feed the chickens and roam around the paddocks behind our house looking for the biggest, blackest mushroom caps to cook for breakfast. After school, Dad would collect us and make random stops on the back roads of Manukau to pick pūhā and watercress. On one of those drives, I spotted a swarming beehive clinging to a post on Redoubt Rd. I yelled to Dad from the backseat and he swung the car around. After a few minutes assessing the situation, he emptied my school bag (a kid’s briefcase) and, with a strategic kick, dropped the whole hive into the bag. We drove home with the bees in the boot of our car. Dad got the necessary gear and knowledge from local beekeepers and soon we had our own honey. He was only stung once, between the eyes. I can still see his face, puffed up like a pitbull.

At home, places like the hot-water closet were spaces where the latest food experiment would germinate or ferment in darkness. The homebrew and ginger beer lived there, and, for a short while, mung beans and alfalfa seedlings — until Dad worked out a large-scale sprouting system in the garage. With the help of a friend, he took a timer from an old washing machine and rigged it to a system that would mist the seeds with water, warmed by a single light bulb. Though he never realised his dream to dominate the South Auckland sprout market, it was not for lack of ingenuity.

In between seasonal work, Dad went away on hunting trips, coming back with venison, goat, pheasant and duck to stash in the big freezer in the garage. When we went up north for the school holidays, he would pack his diving belt, homemade Hawaiian sling, flippers and mask. We kids would watch him kit up and head out into the water with an empty hessian sack tied to an inflated inner tube. By day’s end, we were eating kina, pāua, kōura and kūtai by a campfire.

At 17, I had my first taste of life in another country, leaving my family for a year in the United States as an exchange student. I ate fast food, doughnuts, god knows what from vending machines, and came back with the weight of my bad decisions. I also returned with a new appreciation for my parents, knowing they had expressed their love for me and my brother in the countless hours we spent together as a family growing and gathering our food.

I left the country for a second time in my mid-twenties and lived in the UK for a few years before winding up in America again. I ended up staying there for longer than I thought, due largely to the fact that I had no plan. What I did know was that at some point I would return home, which, paradoxically, made it easier to put down temporary roots.

In my thirties, I found myself doing the thing that as a kid I thought only “old people” like my parents and grandparents did — I started gardening. For a while, I lived in New Jersey, the Garden State. What I learned about gardening as an adult is that it takes skill, planning and so, so much time. With the keepers of knowledge (my parents) a hemisphere away, and seasonally out of sync, the most I could do in the early days was plant easy things like basil and tomatoes. I remember spending a joyful afternoon picking wild wineberries, which look and taste a lot like raspberries. I also encountered a mite the locals benignly call berry bugs or chiggers. In the afterglow of making my first batch of wineberry jam, I developed an itch, then a scabies-like rash.

When I moved south to Atlanta in Georgia, the Peach State, I put in a couple of raised beds and bought some starter plants to create the illusion of success. Squirrels ate everything. A bamboo structure covered in netting finally managed to keep them out, but they let me know they weren’t happy by chewing through the rope of the swing we had attached to a tree. In an effort to replicate my childhood, I planted muscadine grapes, blueberry, blackberry and elderberry bushes, figs and feijoas, and a plum, pomegranate and nectarine tree. Anyone who came over got a tour of the garden, and every bud was pointed out as the promise of fruit.

Every day, I inspected my trees, at one point counting 20 decent-sized nectarines, not yet ripe but on the way. I went away for a weekend and when I got back I walked around the tree again and again, confused. There wasn’t a single one left. Not one half-eaten, mauled piece of fruit; not one pit on ground. The squirrels had eaten everything.

The last place I lived in the US was Maine, the Pine Tree State. The northeasternmost state in the country, Maine is famous for its rocky coastline and lobster dishes. Near the small town of Searsport, there’s a peninsula called Wasaumkeag where I found turkey tail mushrooms, rich with immunity-boosting properties, on rotting tree trunks. Multicoloured, frilly, rigid, they were unlike any mushroom I had ever seen. I picked them and ground them up to make tea. Nobody in the house would drink it except me.

Maine felt like the right place to be at the beginning of the pandemic: isolated, coastal, a place to hunt and forage, with plenty of seafood. In the early days, before we negotiated our bubble, I spent the day out in a boat with a friend of a friend who dived for sea urchins during the winter and knew where to dig for clams. It was a privilege to be together gathering food, reaffirming that natural and important part of my life, at a time of huge upheaval. We built a fire on the beach, just like my parents did when I was a kid. We shared a meal.

I am home now. Mum is still in Auckland and very proud of her garden. She tells me when and how to properly pick her asparagus, loads me up with lemons, limes, persimmons, mandarins and homemade courgette pickle relish. Her plum tree grows right outside the kitchen window, so in the future there will be jam. Mum is also very generous in sharing what is shared with her, so I have a hook-up for free-range eggs and venison sausages.

Dad is in Te Waipounamu, living on our papakāinga and keeping our mahinga kai practices alive. We recently had a traditional duck harvest and, on kayaks, rounded up moulting pūtakitaki on Lake Wairewa into a pen on dry land. Dad processed more than 50 birds with his homemade duck-plucking machine, made from a large barrel with rubber fingers and a rotating base powered by an old lawn-mower engine. He is still keen to figure out how to harvest kiore and I will probably have to help him with that — he jokes about roasting them and eating them kebab-style. Plans are also under way for a large- scale māra, putting back on the land the garden plots our tūpuna once ate from.

Recently, my dad shared stories my grandfather had told him of his early days as a young hunter/gatherer. What made those memories stick out for Grandad was not how good he was at shooting rabbits or gathering kaimoana, but how proud his mother had been that her son came home with enough kai to feed their family of 10. I think memories like these, the ones Dad has from his own childhood and those he has with his kids, motivate him to stay involved in environmental projects that ensure the health of our whenua and water. Without this mahi, we will not be able to carry on living from the land as we do.

Perhaps the biggest change I’ve noticed in the 24 years I’ve been gone is how New Zealand has ramped up the production and export of food for a global market at the expense of our environment. It’s no longer safe to eat kai from some of the places my parents and grandparents gathered. And yet we pay premium prices for the produce, meat and dairy grown and raised here. Coupled with the housing crisis and Covid, the situation has worsened for families who were already struggling to feed their family quality food. People are going hungry.

My childhood probably reads to some people like a fairy tale, but if there was ever a time to get back to the garden, to care for the land and the water, it is now. There is so much to learn, so much to share, and enough to eat if we work together.

—

This story was published in Metro 432 – Available here in print and pdf.