Mar 14, 2022 City Life

Last Christmas, I fell in love again. I already was in love, but the gift my darling gave me that day showed such a deep awareness of my psyche, it was like we renewed our vows. The present was a copy of Bruce Hayward’s Volcanoes of Auckland: A Field Guide and it almost instantly upended my conception of Tāmaki Makaurau. Endless hyperbolic headlines in the property press had warped my conception of the city until it seemed like an amorphous mass of seven-digit sums growing exponentially in value. Magazines would occasionally give evidence of cheap and excellent cuisine from Xinjiang or Sichuan existing among the sums, but, generally, Auckland was living in my head as an abstract bubble of capital slowly inflating and floating out into space.

Volcanoes of Auckland punctures that bubble and peels back the real estate to reveal the rocks beneath, rocks that are anything but inert and ancient. The landscape created by the volcanoes interacts with human history in a dynamic way that is inextricably linked with the mode of their creation. The human development of this area, from early Māori settlement onwards, was driven

by volcanoes — by the shape of the land they formed and by the nature of the rocks they ejected. Bruce Hayward’s book deals with the wonkish details of this geological history, but more enticingly it puts us into context within that history.

And it’s about volcanoes! Volcanoes are thrilling. To a child, they evoke all that is exciting about the world: explosions, lava, noise. Danger. Even today, my dreams are haunted by recurring images of volcanic bombs the size of cars landing around me, falling ever closer like a scene from a Michael Bay film. I can still picture, in a book from my early childhood, a black and white photo of the cast bodies of Pompeii residents cowering in terror from the pyroclastic flow, sheltering their children in their final horrible moments. These images fed into my immature fixations on death as a young boy. I was totally fascinated with the concept, especially its most lurid manifestations as witnessed in Hollywood productions of the 1980s. Car accidents, quicksand, human sacrifice, cannibalism, a fatal plummet off a precipitous cliff-face. The risk of death seemed a necessary counterpoint to the smorgasbord of excitement on offer to me in the adult world if I was just courageous enough to go out and take it.

Today, I live in the suburbs. My life is no Michael Bay film. At best, it would be a comedy of manners starring Alison Steadman. My partner and I arrange our time around school drop-offs and bicker about the remaining hours in the day. Every piece of free time we grant each other involves a rigorously negotiated quid pro quo. So why are my dreams still haunted by volcanoes? What disturbing Freudian well does my fixation flow from? Why, in my darker moments, do I wish for smoke to start pouring out of the ground of a suburban street and lava to ignite and consume the surrounding houses? Does my desire for cataclysmic immolation satisfy some unrequited lust for thrills that exists within me? Is it something even more sinister?

The latent thermal power that exists beneath our feet contains such cathartic potential that it offers our struggles and mild human gripings a sense of proportion. It’s irrational (and possibly psychopathic) to wish for something that would destroy people’s homes and risk people’s lives in order to achieve some kind of transcendent sense of perspective, but here I am quietly wishing it.

In order to cope with this urge in a more wholesome way, I’ve found myself gravitating towards Auckland’s volcanoes. I started spending my leisure time, and increasingly my working time, around them. Pupukemoana/Lake Pupuke drew my focus first because I respect chronology, and Pupuke is the oldest volcano in the Auckland field — according to the latest science (by GNS scientist Graham Leonard and colleagues), it’s 193,000 years old, give or take 2800 years.

I don’t know what I thought I’d find when I started going to Takapuna to visit the lake. I wanted to examine the area, to contemplate the relationship between the Pupuke volcano that erupted so violently all that time ago and the neighbourhoods that surround it today. I wanted to dig beneath my preconceptions and try understand the Shore — to gauge its spirit, to cut into the strata of its history and fiddle around with the rock hammer of my mind knocking chunks off.

On the crest of the hill that overlooks Takapuna to the southeast and Lake Pupuke to the northwest is St Peter’s Anglican Church. The day of my first visit, around Easter this year, I was drawn to it by the sound of a choir floating towards the lake on an otherwise quiet suburban week-day morning. On closer approach, the sound divides into two sectional rehearsals practising different parts of the same anthem, one group of girls in the church itself and another in the adjunct building, both singing varieties of “alleluia”. That sentiment of praise and gratitude colours my sense of Lake Pupuke and its surroundings. Wander- ing down The Promenade towards Takapuna Beach, I in- tone “alleluia” to myself at the good fortune bestowed on this place by forces beyond our control and once beyond our comprehension.

On this bright autumn morning, punctuated by squalls, Takapuna is populated with vital-looking Pākehā women in fitness tights grabbing takeaway flat whites from the Takapuna Beach Cafe , overseen by condominia and pōhutukawa. Along the beachfront is a portfolio of colossal residences whose only occupants seem to be the contractors paid to work on them. A house with a slightly disturbing, presumably child-made Easter bunny artwork displayed in the kitchen window betrays a rare sign of real, dirty human life among the collection of edifices whose main architectural influence appears to be the Getty Museum. Here are properties fortified with schist walls, garlanded with hedges maintained in geometric perfection by crews of men, and protected by keypad-operated gates and private security companies whose signs promise vicious Alsatians at the first sign of trouble.

As I wander on the sand, kicking broken shells, feeling a little overpowered by the real estate, lines from The Front Lawn song “Andy” keep popping into my head:

Just take a look at this beach now

There isn’t much left of the place we knew

when we were kids

When we used to go diving from the rocks

over there

The song is journalistic; it’s gentle yet simmering with repressed rage. Like the best of Don McGlashan’s work, it comes with a late mule-kick to the heart — “On Takapuna Beach I can still see you and I can let myself pretend that you’re still around / I turned 28 last night, if you were still alive you’d be just short of 33.” The line always triggers instant goosebumps and a wetness in the eyes, an emotional alley-oop set up by a litany of observational ironies and seemingly innocuous nostalgia.

I spoke to Don McGlashan about his upbringing, wanting to get a sense of that “place we knew when we were kids”. He grew up in Milford, off Shakespeare Rd, born in the maternity ward of North Shore Hospital on the shores of Pupuke. To the five-year-old Don, the lake stood as a sort of impenetrable boundary to the world beyond, “a subconscious sinkhole for people who live around it”. It was rumoured to be bottomless. “I remember my big brother would come back from expeditions to Takapuna and to Black Rock and it just seemed to me impossibly far away and adventurous to go that far on his bike with his mates.”

If the lakefront and the beaches represent dreams achieved, a place to end up and tend your pile, the part of Milford on the western side of Shakespeare Rd where McGlashan grew up is still the scene of dreams in the process of being constructed. It is archetypal Auckland suburbia: not flashy, not stylish, not attractive; a chowder of unpretentious mixed-aged homes bearing the evidence of five generations of Kiwi Dreaming.

On 17 December 1915, as Anzac troops were with-drawing from Gallipoli, the Observer ran an advertisement for an auction of Lake View Estate, the subdivision that birthed this part of Milford. This was Auckland’s bourgeois frontier, farmland being opened up for new families to establish lives, while on the other side of the world young men’s bodies were being reassembled into cubist sculptures. “Lake Takapuna, like a great mirror, lies immediately in front, Milford Beach, Takapuna Beach, Auckland City, and the whole Hauraki Gulf also meet the eye.” Today, most of these natural features, touted to help sell the sections (priced from £22 to £71), no longer “meet the eye”, obscured by everything that subsequently grew upon the land. Homes, trees and telegraph poles. Garages, conservatories and sleepouts. A second floor. A granny flat. A trailer sailer out front. The hospital. A retirement home. A business park.

The most desirable sections in the Lake View Estate auction were those closest to Wairau Creek. The creek bisects the suburb and also marks the edge of Pupuke’s tuff ring, the gentle slope of bedded ash built up around Pupuke by the lateral base surges its violent eruptions produced. I spent a morning following the streets of Milford along the course of the creek, texting Don to hound him for more memories. “My older brother and his mates built boats called ‘tinnies’ out of individual sheets of corrugated iron — the bow just folded and lashed together, the stern a piece of wood, and the whole thing waterproofed with tar off the road. My friends and I made a raft once — I’d been reading Huckleberry Finn — but it sank.”

After the Harbour Bridge was opened in 1959, the area experienced a rapid urbanisation as farmland quickly became city. The wetlands that fringed the creek became Wairau Rd and mechanics’ car parks, and the rainwater that had once gently inundated the swampland now had nowhere to go but downhill. The desirable Milford sections became the site of increasing numbers of floods throughout the 1960s until it was deemed necessary in 1972 to turn the creek into a concrete culvert — “an act of remarkably callous violence on the aesthetics of the place”, according to McGlashan. The concreting of Wairau Creek subsequently resulted in even more flash floods, though now they funnel violently down the artificial channel like a suburban Huka Falls rather than flowing sedately through people’s backyards and homes.

This chain of events illustrates the Pākehā frontier mindset, in which our fixation on our own little fortress, that title on a LIM, leads to competing interests that damage the collective good. I asked Martin Te Moni from Ngaati Whanaunga about what this kind of treatment has done to the land. “Has the mauri of all those streams that roll into Te Waitematā been enhanced… has the mauri changed? ’Course it has. Would we have done the same sort of things the same way? No… We can’t even get any food down the front now. That [Waiwharariki/Takapuna Beach] used to be one of the places our people used to get food from… So, is the mauri enhanced? No. Is the mauri still there? Yes. What’s the value of it now? Very, very, very low — non-existent. Can we do something to fix it? Of course we can.”

A volcanic eruption is not only an act of destruction but also an act of creation. In the case of Pupuke, it created a beautiful lake. The lava and tephra that destroyed the forest eventually broke down into good-draining volcanic soils that made the surrounding area more fertile than it had been previously. The new built-up land, fortified by basalt lava flows harder than the sedimentary rock that

it covered, created a resilient buffer to erosion which has thus far prevented the sea from eating away more at the land. Without the eruption, much of Takapuna and Milford would likely be mangroves. And in some thematic symmetry, while the area has profited enormously from this geological good luck, this wealth brings with it an obverse destruction, eliminating heritage, suppressing diversity and youth and replacing it with inequality, monoculture and stagnation. The capital locked up in real estate has ossified culture here — or, to use a more apt analogy, the hot flow of molten culture that once poured through Takapuna began cooling in the 1960s and has now hardened into rock, replaced by empty signifiers codified by property developers. On Anzac St is an apartment building called The Sargeson where, according to Harcourts Cooper and Co, “aspects of the local environment, in particular the dark volcanic colours found throughout Takapuna, were inspirations for the chic palette of exterior materials”. On Northcroft Street, the Sentinel, 30 storeys of luxury apartments with a “discrete (sic) concierge team and … proximity tag elevator”, is capped with a harakeke kete motif.

I initially got in touch with Martin Te Moni after reading an Eke Panuku Development Auckland brochure, which talked about “working with mana whenua (to enrich) the way we understand place”. I couldn’t help but wonder whether this was just organisational window dressing, a slightly better-thought-out version of the kete motif, or something more substantial.

“Rightly or wrongly, decisions were made about doing stuff in the area of Takapuna. Things were done. Did we like some of that stuff? Well, not really,” Te Moni says. He tells me about the concept of taunahanaha, the naming of a place, and how when a name is changed, it changes the whole thing. My brain is whirring with the idea that countless narratives were erased in the remembrance of mutton-chopped Englishmen. “What has happened in Tāmaki Makaurau is that — I’m not being critical, it’s just how it is — local boards have come on every four years over a period of 50, 60, 70 years… and have decided to put names in for new streets, even change the names of ones that are already named.”

A recent act of naming by Panuku in concert with mana whenua was Toka Puia, a parking building next to the Sentinel. How could a multi-storey car park relate to mana whenua narratives, how could that enrich the mauri? “The toka puia was a spring in that particular area which has been covered over and that also linked up with two other streams in that area, so it was about acknowledging that. Rather than having the spring there, the car park was to acknowledge… that spring that had been forgotten.” While there may not have been a car park in pre-colonial times, “Takapuna was one of those places… not only for navigation east–west, but it was also for food, it was also for getting closer to some of the ranges, for travelling, traversing… You might have a space where you stopped to have a rest, and there were places that were named because of that — a halfway point where people would stop and camp, rest up… Those sorts of things were happening way back in the early days. It’s just that all that stuff’s lost. And it was about re-establishing some of those things.”

In the course of our conversation, any doubts I had about the value of this kind of collaboration, that it might be some kind of bureaucratic box-ticking exercise on the part of the council, were erased. “Working alongside and with Panuku,” Martin says, “allows us the opportunity to acknowledge those things that have been buried, have been silent.”

A kilometre south of The Sargeson and its “chic palette of exterior materials” is Frank Sargeson’s house at 14a Esmonde Road, clad in grey asbestos. A plaque outside reads: “Here a truly New Zealand literature had its beginnings.” I find it depressing, not because of its spartan exterior, but because it feels dwarfed by the four lanes of Esmonde Rd relentlessly conveying traffic to and from the motorway, and even by the two 1980s townhouses dumped where the garden used to be.

The Sargeson house is the keystone attraction in a booklet of North Shore Literary Walks compiled by local author Graeme Lay. I spent a morning following the Takapuna route past a collection of writers’ addresses either long demolished or hidden in their own ordinariness. In the end, I got far more insight from the words of the writers than from blandly gawping at the properties in which they once wrote: Janet Frame writing in An Angel at My Table about Sargeson sunbathing naked against the east wall of the bach, a daily ritual to treat the scar of his tuberculosis treatment; or her typing “the quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog” to mask the silence of her inactive typewriter as Frank brought her tea to the army hut, his “footsteps rustling in the long grass” along a path now scythed and cobbled as a driveway for those townhouses. Mosquitoes “swarming from the mangrove swamp at the end of the road” while Janet and Frank read Tolstoy together. “And as we talk we are no longer on Esmonde Road, we are with Pierre, gone to see the War and looking on the face of Napoleon.” The same way this literary odd couple, sitting on high stools at the kitchen counter discussing books, astral-travelled from that little bach to European fields of battle in the 19th century, I could astral-travel from Takapuna’s IRL Barfoot brochure to the North Shore of the mid-20th century.

Here I would find Hone Tuwhare witnessing the forced exhumation of his stepmother’s relative Puhata from the nearby urupā at Awataha:

his face glass-gouged and bloodless

his mouth engorging clay

for all the world uncaring…

Here I would encounter Sargeson’s Mrs Crawley in An Affair of the Heart waiting futilely, night after night, in a bus shelter in Castor Bay for her beloved Joe to return. Here I would avert my eyes as Curl Skidmore in CK Stead’s All Visitors Ashore performed heroic feats of sexing with the soprano Felice Stockman, and make a hurried exit from a beachside cottage in Graeme Lay’s The Mentor as Paul Hopkins and Nicola Drawbridge “came and came and came”. (Turns out this astral traveller is a prude.) And here, again and again, I would find Rangitoto looming, dark and totemic, a constant metaphoric presence just waiting to be exploited. Across the channel, Rangitoto is connected to Takapuna as shadow is to light. It contains an inhuman darkness, a deep enigma that is in opposition to Takapuna’s very suburban lack of mystery.

When the young Don McGlashan became old enough to cross the lake’s insurmountable barrier, he took piano lessons on Minnehaha Ave from Eric Bell, who disciplined his errant left hand with a stiff whack of his ruler. “My dad used to say with a sort of slight awe that Eric Bell had ‘been on the radio’. There was a period evidently where National Radio would have a little gap and to fill the gap they’d say, ‘Now we’re going to have a song played by Eric Bell on the Novachord’, which was some kind of organ. My father was pretty impressed by that. I just think of him as this terrifying man, but he was probably a musician who was living in a slightly out-of-the-way part of Auckland where musicians could afford to buy a place, just in the same way that I live in an out-of-the-way part of Auckland where musicians can afford to have a place.”

It’s tough to picture that kind of bohemian history in a street of quasi-oligarchic residences, but sure enough it existed. Along the coastal walkway between Thorne Bay and Milford Beach, you can glimpse a lone remnant from this time, the former home of Clifton and Melva Firth. Dwarfed in size and leveraged capital by its neighbours, it clings stubbornly to the rock, a rustic barnacle in white weatherboard.

Clifton Firth was the society photographer of Auckland in the 1940s and 50s, capturing many of the city’s notable figures in noirishly shadowed studio shots bearing the influence of European modernism, via classic Hollywood portraiture. His photographs have a glamour that doesn’t necessarily match up with the spartan, nation-building literature of the time. But conversely, it’s a pleasure to see some of these writers, whose words sometimes seem to come off the page dressed in tweed and reeking of pipe smoke, indulging in a moment of vanity and pretension in a time when vanity and pretension were not valued characteristics.

Until recently, the house was inhabited by the Firths’ son Paul, who died in June this year. I met up with Paul’s old friend Kay Brown, classics teacher at Westlake Girls High School for over 30 years, a fact she shared with mortified astonishment. It was a stormy day at Black Rock, with a gale blowing in from the northeast and the channel murky and white-capped, more like the south coast of Wellington than its usual limpid, gentle Mediterranean feeling. We stood chatting in the garden outside the old house while Kay reminisced about Paul, “a sort of Peter Pan character”, and her visits to the house as a teenager in the early 1970s at Paul’s invitation. “We attended…long sessions of debate and poetry reading… Clifton, as I recall, presided in patrician fashion, whiskey in hand, over these gatherings, no doubt vaguely bemused by the crudely framed enthusiasms of our gang, in our tie-dyed ensembles and batik prints… The Firths were inspired by Rewi Alley and had gone to China to meet him, I think. They were certainly members of the New Zealand China Friendship Society… These were the Norman Kirk years, and a certain optimism prevailed in the air.”

Our conversation was brought to a halt by an irritated man who stepped out of the house, which we had presumed to be deserted, to ask us what we were doing on the property. He was evidently taking care of the estate. There had been a theft there recently and he was suspicious. Kay attempted to explain the reason for our presence there, but her softly spoken words were blown away on the gale and we beat a retreat southwards along the seawall towards Thorne Bay.

In Bruce Mason’s End of the Golden Weather, his characters Joe Dyer and Bob Ferguson, twenty-one years old, are two “bronzed animals”, “lean and body-proud”. They perform homoerotic acts of agility on the beach; “The sun beats down, licking our flesh with a searing tongue.” On a hot day at Thorne Bay these days you can see Joe Dyer and Bob Ferguson’s descendants tanning their predominantly European skins, crammed on to the narrow ramp of sand that plunges down from the mansions, framed by black lava, into the Rangitoto Channel. It is one of Aotearoa’s most perfect little beaches and if you’re there at the wrong time or in the wrong headspace, it can turn you against humanity.

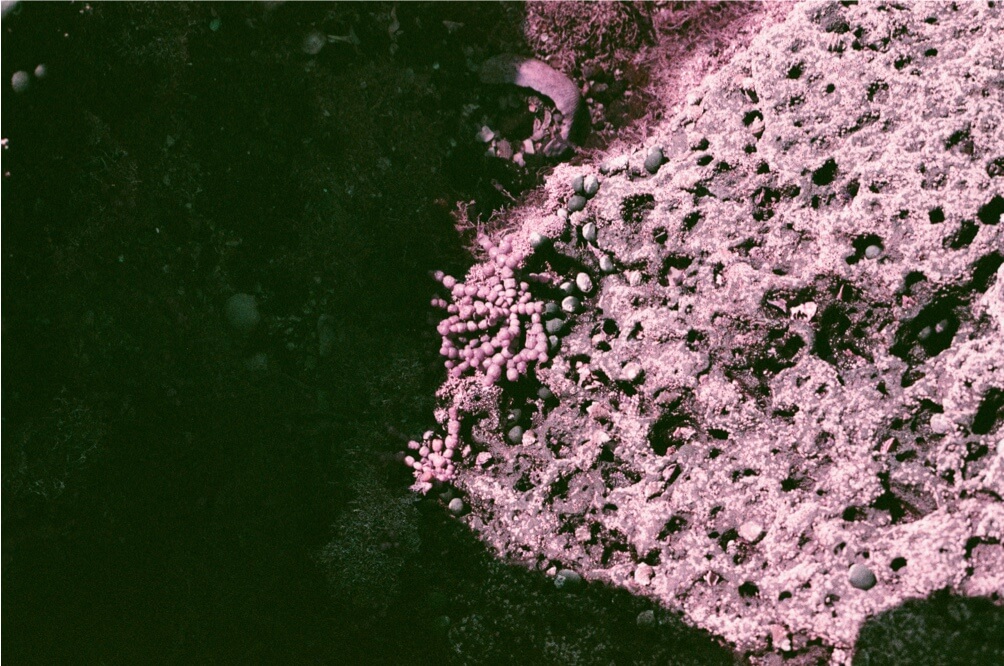

But geology is an excellent mindfulness practice. On one of those baking Minnehaha days when you’re struggling to reconcile the conflicting feelings of misanthropy and lust, look down at the rocks beneath your feet. Consider the acres of lava that flowed through here, burning down a forest — evidence of which remains etched in negative in the form of hollow kauri trunk-shaped holes in the rock. You can turn away from the concerns of the day — those nagging feelings of underachievement in your career, failure to invest in the housing market and regrets about having been an inattentive father — and walk into a story told over eons whose progress concerns you not a jot. For once, the fact of your insignificance in space and time is not terrifying and unanswerable but a comfort.

Pupuke’s eruption some 190,000 years ago is an unfathomable amount of time in terms of human history — approximately 7600 generations or two-thirds of the entire history of Homo sapiens — yet if not quite a blink of the eye, it’s a mere couple of indulgent yawns in terms of geological time. The Southern Alps, a relatively youthful geological construction, have been uplifted (and eroded) to their current state over the last 23 million years, although the oldest sedimentary rocks contained within the Southern Alps are up to 500 million years old. Recently, a piece of peridotite found near Wānaka, a remnant of some ancestral continent that once existed where Zealandia is now, was aged at 2.7 billion years. When you start juggling these kinds of numbers in your brain, the activity of Auckland’s volcanoes becomes startlingly contemporary.

Like imagining the size of the universe, to consider geological time is to think oneself into near non-existence. Even the overwhelming existential nightmare of climate change is made ridiculous by the briefest consideration of geological time. In its sweep, oceans rise and fall by hundreds of metres in a heartbeat; primeval forests are wiped from the face of the earth and regrow, merely to be destroyed once more. Drawn out over hundreds of thousands of years, our anthropogenic apocalypse will be another blip on a graph, evidenced in the stratigraphy by a layer of plastic.

About eight weeks into the recent lockdown, as the horizons of my life begin to extend beyond my backyard and the road up to the Super Value, I take a trip out to the Shore. It’s a still monochrome morning on Milford Beach. The gulf is molten platinum, flashing a blinding white on the horizon where the layer of low cloud breaks. The only colour comes from a patch of sunlight on the western flank of Rangitoto, illuminating the olive green of pōhutukawa forest above the red and white candy-striped lighthouse on the rocks. People are in their lockdown routines, out for morning jogs and strolls. There is little sound other than the white noise of tiny swells slopping on to the beach and the fast rhythmic jangle of tags on the collars of passing dogs. For a second, my eyes, struggling with the glare of the low sun, register a person walking on water at the north end of the beach. A second glance reveals a stand-up paddle boarder cutting a wake across the millpond.

I proceed around the Milford–Takapuna walkway next to the basalt foreshore, passing Black Rock and the old Firth house and crossing Thorne Bay beach, today emptied of its buff and be-thonged weekend clientele and totally quiet save the sound of home renovations and the rush of Pupuke water pouring out of a crack in the rock. As I continue along the seawall, I can feel the sun’s warmth growing in me. I resolve to head out on the rocks at the top end of Takapuna Beach — the fossil forest — and let the humbling, healing power of geology work its magic. To sit mindfully with the sharp basalt digging into my backside; to feel its warmth, its rough, holey surface on the palms of my hands. To ponder the awesome heat and power which consumed the forest that once stood here. To consider that my presence here in time and space is one of pure luck.

After a few minutes, I turn around and begin to head towards the beach. There’s a couple smiling in my direction, beginning to walk towards where I’m coming from. I think, “They must be excited to see the fossil forest as well.” After I pass them, I look back to watch them in the throes of a sublime geological experience and notice that they’re not looking at the rocks at all. Out in the channel there’s a pod of a few dozen dolphins doing the joyous leapy things that dolphins do. A ripple of awareness spreads and people start gathering on the rocks exclaiming such profundities as “Wow” and “Awesome!” Nothing else needs to be said. It is wow. It is awesome. I feel myself welling up at the audacious ease with which nature can sweep aside our petty little issues with such flagrant displays of beauty. As if to chide me for this moment of grandiosity, a fluffy little poodle with a lockdown haircut stops a few metres in front of me and, facing me, begins to painstakingly extrude small shits on to the sand, its tail twitching towards Rangitoto across a sea filled with dolphins.

–