Jun 16, 2016 Urban design

For over 100 years New Zealand’s professional architecture organisation has never had a female practising architect at its head. Christina van Bohemen has changed that. She talks to Metro about diversity, her own late start and how much better Auckland is these days.

She founded Sills van Bohemen in 2001 with her partner in work and life, Aaron Sills. Architects have long declared St Kevins the best living room in Auckland. At the moment it’s undergoing a makeover, dolled up with new black-and-white floor tiles, so far still retaining the magic. It’s set to become “the new Ponsonby Central”, though the jury’s still out on that.

Van Bohemen’s also got a new role. At 53, she’s president of the New Zealand Institute of Architects, the first female practising architect to hold the role since the august organisation was formed in 1905. Only one other woman has held the post: Helen Tippett, the first female professor of architecture in Australasia, became NZIA’s first woman president in 1989. It’s taken only 27 years for another woman to get the nod. Gender diversity hasn’t been a strength of the profession and van Bohemen’s appointment is immediately seen as a harbinger of change.

We settle in at Bestie , the cafe at the end of the arcade, with its glorious outlook to Myers Park, to the accompaniment of grinding sounds so loud we can’t speak. A noise like a cry of distress as some piece of intractable material — timber, perhaps masonry — refuses to yield to the machinery of change.

The machinery of change is grinding slowly, too, for women in architecture. Van Bohemen mentions a study released this year by the American Institute of Architects. It found women strongly believe there is not gender equity in the industry; women and minorities say they are less likely to be promoted to more senior positions and gender and race are obstacles to equal pay for comparable positions.

The statistics, says van Bohemen, are pretty much the same in the UK, US, Australia, Canada — and New Zealand. “Anywhere between 21 per cent and 25 per cent of registered architects are women — so pretty small numbers.” Yet when it comes to the schools of architecture in these same countries, between 50 and 60 per cent of the students are women.

“It’s difficult to know quite when the drop-off happens,” says van Bohemen, “because while those percentages represent those registered, there are a bunch of other people working in architecture who, for one reason or another, don’t go through the registration process.” Five years ago, the editor of London-based The Architectural Review, Christine Murray, went in search of the missing 25 per cent. She found many female architects were not afforded the respect, or the pay, of their male colleagues. “If they had reached director level, they were either married to their co-director or, more often, found in roles such as HR, interiors and sustainability. Some had ducked the glass ceiling by founding their own practice and were quietly labouring on in relative obscurity.”

Others joined academia because of a perceived better work-life balance. Many had left architecture altogether.

Whatever way you look at it, says van Bohemen, it’s not good. “Whether our organisation is chaired by a man or a woman, issues of diversity, of which gender is one, are something we need to address.” Is the profession imbued with systemic sexism? “It’s not my experience,” says van Bohemen diplomatically. “I think there is unconscious bias. I’ve run into one builder who I decided was a misogynist, but he might have just hated architects. For the most part I think I’ve probably been quite lucky.”

AUT’s Governor Fitzroy Plaza (top) and the streetscape of university buildings as seen from Wakefield St. Van Bohemen says Jasmax’s AUT buildings work at street level as well as on the skyline.

AUT’s Governor Fitzroy Plaza (top) and the streetscape of university buildings as seen from Wakefield St. Van Bohemen says Jasmax’s AUT buildings work at street level as well as on the skyline.

In 1996, as an architectural graduate at the firm Jasmax, she worked as part of a team where the quantity surveyor, engineer and architect were all women. “The client said they were the most efficient meetings they ever had.” But there came a time when it wasn’t so good. “I left Jasmax when women seemed to get to a point where, for whatever reason, we felt dispirited and we decided to leave.” That was 2001.

There is a higher percentage of senior women at Jasmax now and van Bohemen points to other examples, such as Rachael Rush, who heads the firm Klein. “There are some women who head their own practices, who do substantial work but are less well known. The numbers are still pretty low across all corporate practices.”

Low, but not unheard of. In the large firm of Warren and Mahoney, Vanessa Carswell is one of two female principals. Carswell told ArchitectureNow, “I know first hand that perceptions are changing… There is more of a realisation now that it’s advantageous to have both women and men in senior roles.”

Van Bohemen agrees change is slowly happening — something she attributes to the work of Architecture+Women, an educational and advocacy group formed in May 2011 to advance the interests of women in the profession. But New Zealand trails the Australian Institute of Architects, which has adopted the equity guidelines published by Parlour, an Australian organisation dedicated to promoting gender equity in architecture. One of the projects for van Bohemen’s presidency will be to adopt a version of those rules, in collaboration with Architecture+Women, as guidelines for the NZIA.

Her pathway to becoming an architect was circuitous. She grew up in Havelock North, the youngest of five. Her father emigrated from Holland in 1951; her mother arrived here from England in 1949. She and her sister were sent to Erskine College, a Catholic boarding school in Wellington. “We were a classic immigrant family, constantly aware that our parents had this new life in New Zealand. We didn’t have any relatives. We had a name we had to spell out all the time.”

“We were a classic immigrant family… We had a name we had to spell out all the time.”

Sills van Bohemen’s award-winning Hurstmere Green in Takapuna.

Sills van Bohemen’s award-winning Hurstmere Green in Takapuna.

ASC Architects’ Franklin Library.

ASC Architects’ Franklin Library.

Her seminal architectural moment was a sixth-form history course on engineering and architecture of the 19th century. “That course introduced me to what happened in the beginning of modernism. It kind of inspired me when I did my BA.”

Despite her enthusiasm for architecture, though, that BA was in English literature, and gained at Victoria University of Wellington. After graduating she decided to travel. First stop was New York, where her brother Gerard had just taken up his first posting as a junior diplomat. (He’s now ambassador to the United Nations.) She spent the days looking at buildings, attending lectures, reading and absorbing Manhattan. “Seeing things like the Seagram building; that was all pretty exciting. I had an office that looked back to the Chrysler building.”

In London, her obsession with architectural history was fed by working in administrative roles in various practices. Meeting New Zealand architects Chris Moller (these days host of the TV series Grand Designs New Zealand) and Alastair Scott there was the tipping point. “A conversation started and that led to, ‘Why don’t you go and study?’”

She kept the plan secret. “I told one of my brothers and just a few others. When I got brave enough, I told more people.” Lots of them told her she was crazy.

At 29, she started at the School of Architecture at Victoria. “I seemed really old. Getting into Vic required some maths and physics and that was very difficult. After I passed maths with a C, I felt I could do anything.”

There was similar impulsiveness in the setting-up of her firm. She had met Aaron Sills in 1999 and decided to leave Jasmax, but she didn’t have much of plan. He suggested setting up shop together. They wondered about the pressure it would put on their relationship. “So we did the whole thing — living together and working together. We figured the risk was, ‘Well, we just might break up sooner’.”

Fifteen years later, the practice has grown to five. She says she and Sills complement each other. “He’s a really clear thinker whereas I’m much more intuitive and excitable. When you work with somebody you are in a relationship with, you are way tougher with each other than you would be with a colleague.” Is he a harsh critic? “Probably not as hard as I am on him. I think I’m a bit mean.”

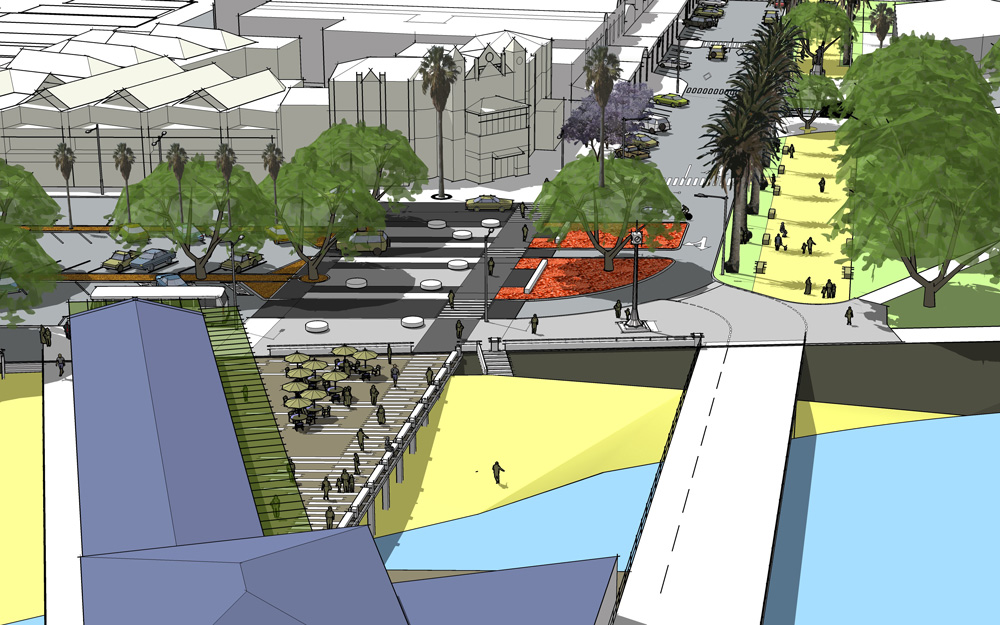

Sills Van Boheman’s Devonport town centre masterplan.

Sills Van Boheman’s Devonport town centre masterplan.

Ask her about the architecture she admires and van Bohemen talks not about buildings but the spaces between. An unashamed urbanite, she walks, rides and lives the talk. “When I think about the Auckland I arrived in 20 years ago, it’s so much better now. It’s got places that you want to go to.” Home is a Freemans Bay apartment in one of the enduringly liveable three-storeyed Star Flats, designed in the 1950s by emigré modernist architects in the housing division of the Ministry of Works.

Work is a short ride to Karangahape Rd. “Lots more people are biking like me — not in Lycra, on city bikes. I don’t always ride the pink path to work, because I often go up to Ponsonby Rd and get some bread for lunch, but I always ride it home. It’s enlivened the city. It’s joyful.”

She loves the Lorne St shared space fronting Auckland Central Library. “If you go there before the library opens, or at the end of the day, it is filled with people sitting on the steps using the free Wi-Fi, and then there are the skateboarders. It’s a real gathering place.”

Another new public space that gives her real joy is the extension of Lorne St, passing through AUT and up to St Pauls St. “That strip of buildings done by Jasmax is fantastic because they have created quite elegant buildings on the streetscape and the skyline. But at street level they have made really good places to sit, to stay, and shelter. Watching people arrive the other day, it was just buzzing. It feels as though the university is there on the street. That’s a real example of the transformational nature of architecture.”

She talks in a similar way about Franklin Court, the new enclosed civic forecourt of the Franklin library and arts centre created by ASC Architects. In its own work, Sills van Bohemen has also carried the flag for better public spaces — as seen in the decidedly transformative, award-winning Hurstmere Green in Takapuna and the firm’s winning of the Devonport town centre masterplan competition in 2004 and subsequent Marine Square concept design.

As for her role as NZIA’s president, van Bohemen supports the endeavours of her predecessor, Pip Cheshire, to widen the role of the institute to something greater than simply looking after the professional needs of its 3000 members.

“Our role is to promote architecture and its value to the community.” That means serving on urban design panels to ensure better architectural outcomes, but also fostering wider public discourse.

“We hold a lot of knowledge and we can lend expertise to the discussion about how to best build the environment and what the value of that is in terms of cultural, social and economic benefits.”

“The challenge for us is to make ourselves relevant to the younger ones coming through.”

The key to maintaining a wider public relevance for the NZIA is to ensure that from the time they start at university to when they find a job in architecture, students are part of the institute. “The challenge for us is to make ourselves relevant to the younger ones coming through.” She also believes it’s vital that more architects engage, not just in public debate, but in public roles — such as branch positions, the registration board and graduate development roles — as van Bohemen has done throughout her career. “The first reaction might be, ‘Oh we’ve got too much to do.’ But if we want to engage the public in architectural issues, we have to make ourselves available.”

At the beginning of her two-year term, Christina van Bohemen is about to crank the machinery of change.

“When I think about the breaks along my career which have given me a new experience outside my traditional work trajectory,” she says, “it’s because somebody made an offer or invited me to do something and I said yes.” With gender diversity very much on the institute’s agenda, she may also find she now has to say no.

This was published in the June 2016 issue of Metro.