Sep 7, 2022 Urban design

At his house near the tip of west Auckland’s Te Atatū Peninsula, Ben Gracewood peers across the road to where a section has been cleared to make way for 13 new town- houses. Two other properties have been bowled nearby. On the 10-minute walk to the nearest bus stop, he passes three other developments. Gracewood is in favour of the new housing. He likes the buzz it brings to the town centre and the influx of shops keeping up with the influx of residents. But he says the peninsula is starting to groan under the pressure. At peak times, it’s a 50-minute bus ride from his house to the city centre. At school drop-off and pick-up times, it often takes 20 minutes just to get from the peninsula’s shopping centre to the Northwestern Motorway on-ramp. Recently, he was almost knocked off his bike by a truck on its way to a building site near his house. When he’s home, his daily life is set to the soundtrack of construction noise.

Meanwhile, on Paget St in Freemans Bay, a pīwakawaka flits between a pruned hedge and a kōwhai tree. It’s a two-minute stroll from Ponsonby Rd, where frequent buses run all day. In 2024, it will be a 20-minute walk from two City Rail Link stations. Despite that, it’s entirely filled with single detached villas. The Sky Tower looms large against the blue horizon. There are no diggers. In between the occasional whooshes of passing cars, silence persists.

As with many of the distortions in Auckland’s urban fabric, the contrasts between these areas find their origin in the dull pages of council zoning maps. They colour Te Atatū and poorer areas like Manukau, Massey, Henderson and Mt Roskill in hues of deep orange, marking them down as suitable for the development of townhouses and apartments. The richer suburbs ringing the city centre are shaded differently. Behind small pockets of orange, their streets are painted in suburb-spanning lashings of light brown and overlaid with a designation restricting them to a single house per section: “special character”.

These maps are impenetrable to some people. But to many who understand them they are inequity coded on to the city. Waitākere councillor Shane Henderson says they speak of a council that has no qualms saddling his mostly working-class ward with as much development as it can take. When it comes to Paget St and others like it, though, the maps send a different message: keep out. “These are gated communities without the gate,” he says.

The borders of those communities were drawn in a document that was meant to bring a measure of fairness and equality to Auckland’s urban development. When the Unitary Plan was passed by Auckland Council in 2016, councillors hailed it as a potential cure for the city’s spiralling housing crisis. There was reason for their optimism. The plan opened up land for roughly 900,000 new dwellings. Planners trumpeted its “compact city” approach, which they said would ensure development concentrated around public transport nodes and town centres.

Housing advocates say the compact city has always been a myth, and the idealistic language about the Unitary Plan obscures an unjust reality. In their eyes, it delivers something more akin to a “doughnut city”, drastically limiting intensification within two to four kilometres of the city centre, and forcing people to live in higher density, further out. A former council official who worked on the plan says that warped approach was by design, and councillors from the isthmus were allowed to adjust the maps to ban dense development in their wards. “A lot of it was done politically,” the former official says. “They let councillors choose which areas to upzone. They didn’t follow the compact-city philosophy in a lot of ways.”

The carve-outs came at a significant cost. Character advocates like to say the restrictions cover only 3.6% of the city’s residential land, implying they’re a small price to pay to protect the kauri villas and bungalows built during Auckland’s early expansion. But in that statistic, ‘residential land’ includes every property within Auckland’s rural–urban boundary, from Papakura in the south to the foothills of the Waitākere Ranges in the west, Howick in the east, and Warkworth in the north. Maps produced for Metro show the percentages are far greater in central Auckland, where land values are highest. Character protections cover 41% of the residential land within five kilometres of the city centre. That percentage rises in city-adjacent suburbs, reaching 94% in Grey Lynn Central and 91% in Ponsonby East. The restrictions have choked growth near rapid transit, including along the future route of the City Rail Link. Around 80% of properties are subject to restrictions in central Mt Eden and near Eden Park. Nearly 70% are cut off from dense development in Kingsland, which is also expected to be a key link in the government’s planned light rail line. In the city’s best-located suburbs, the gates are locked tight.

Six years on, the Unitary Plan’s backwards, outside-in approach to growth is etched into Auckland’s built form, visible in the waves of townhouses going up around Gracewood’s house in Te Atatū, and conversely in the tranquillity of the leafy streets of Ponsonby, Herne Bay and Grey Lynn. Penny Hulse, Auckland’s deputy mayor at the time the plan was passed, now looks back on it with a tinge of regret. “We allowed a lot of housing, but we also baked in a lot of inequality,” she says. “It is inequitable. And it’s politics at play — the politics of power.”

Special Character area coverage. Data visualisation by James Mulrennan

Lately, the government has been making meaningful efforts to fill in the doughnut city, by forcing Auckland Council to allow dense housing in the places where it makes most sense. The government’s National Policy Statement on Urban Design (NPS-UD) compels councils in our five largest cities to zone for six-storey apartments within walking distance of town centres and rapid-transit stops. In December last year, it doubled down on that pro-density direction, passing the Resource Management (Enabling Housing Supply and Other Matters) Amendment Act with support from National, the Greens and Te Pāti Māori. It allows people to build three townhouses by right on most sections in residential areas. Councils have been given until 20 August to incorporate the new rules into their plans. Auckland’s adjustments will be assessed by an independent panel, and the council has until 31 March 2024 to accept or dispute its findings. If the council rejects the panel’s advice, the final decision on its zoning rules will rest with the Minister for the Environment. Though councils are allowed some discretion, the current minister, David Parker, has warned they won’t be able to keep places like Ponsonby, Grey Lynn or Freemans Bay preserved in amber anymore. He’s told the media that suburb-spanning development protections will no longer be permitted.

Housing advocates initially rejoiced, but their joy has been short-lived. Several councils have launched a rear-guard action against the legislation, with Auckland Council making a particularly aggressive effort to preserve as much character as possible. Under its initial response to the NPS-UD, about 16,000 of the city’s 21,000 character houses are retained. More than 90% of the residential land in city-fringe areas including Grey Lynn Central and Ponsonby East would stay off-limits for anything more than one house per section. Paget St would remain pristine.

On a Zoom call from a conference in Australia, the council’s chief planner, Megan Tyler, hedges slightly when asked if she has received legal assurances that her team’s approach complies with the NPS-UD. “I’m absolutely…” she says, trailing off. “I’m fine that it’s legal. Yep.” Many people interviewed by Metro, including the Minister for the Environment, planners, lawyers and high-ranking government officials, say that’s not correct, and that the council is stretching the law to breaking point, and likely beyond. They see councillors and officials running something akin to a character protection racket, ignoring Parker and the clear direction of the legislation, in what they suspect is an effort to cater to affluent suburbanites and Nimbys.

Scott Caldwell, a spokesperson for the pro-density Coalition for More Homes, says he wouldn’t have minded if the council had tried to protect a few high-quality, architecturally or historically significant streets. But the sheer extent of the council’s proposed protections makes the proposal unfair and likely illegal, he says. “It’s 3% of the overall city but 90% of the most desirable places to live if you want a compact city. The harm is that no one gets to live there apart from the people who already do, and anyone who’s lucky enough to inherit one of their houses.”

Andrew Braggins, a partner at Berry Simons Environmental Law, says the council’s approach simply doesn’t pass muster. “To carte blanche, and in an almost grasping sense, try to protect a whole swathe of special character in the prime areas for intensification is illogical and contrary to the intent of the NPS,” he says. “When someone does an assessment of the cumulative effect of the special character areas, I think they will fail. And it’s concerning that the council hasn’t taken the step back to actually assess that cumulative impact. It’s crazy.”

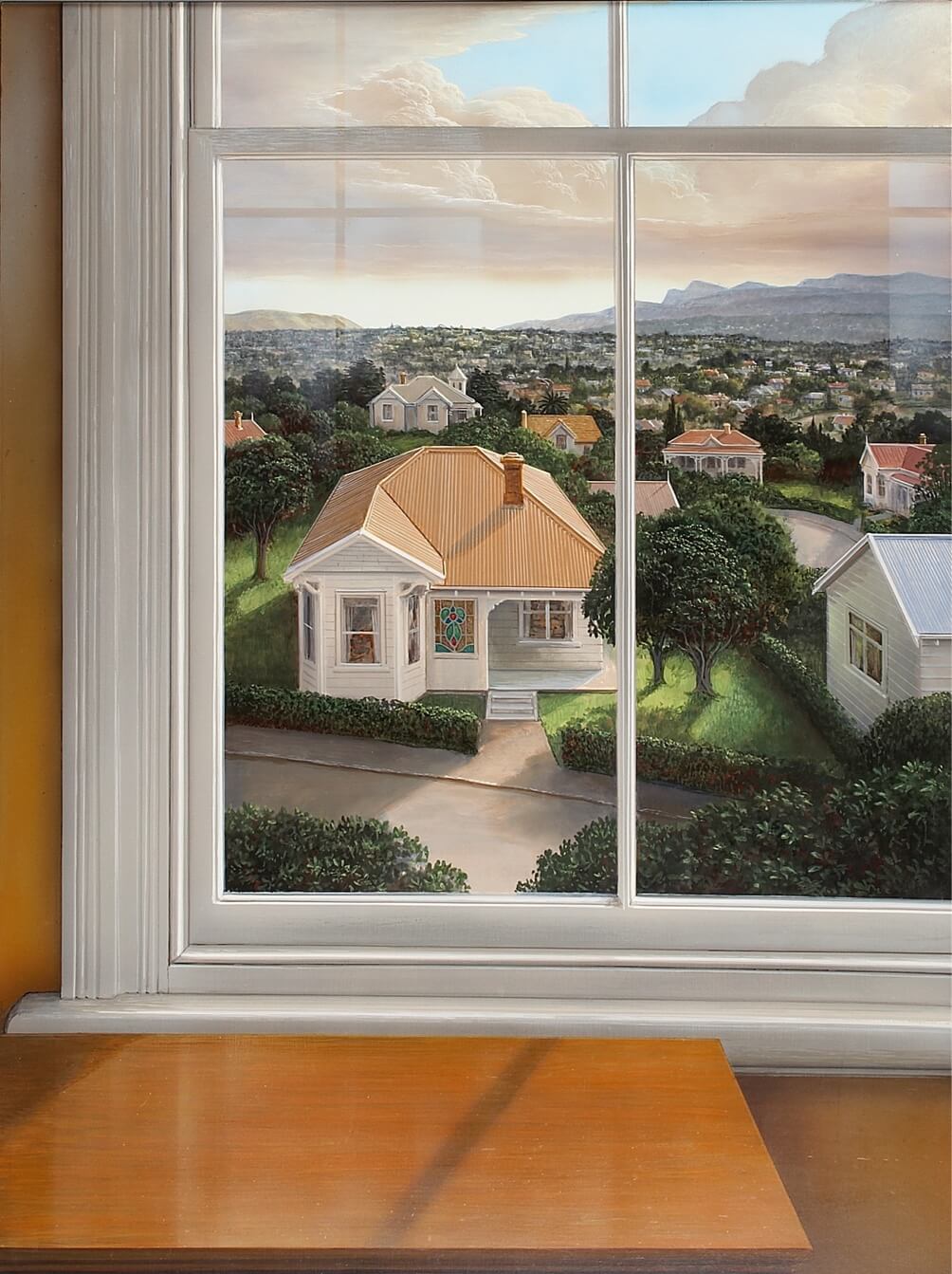

Western window, 1987

At a ratepayers’ meeting in Birkenhead on a Tuesday night, a different gospel is being preached. The suburb is one of a minority set to lose a substantial number of its character protections under the council’s proposed plan. These local homeowners are petitioning the council to thumb its nose at the government and reinstate the restrictions. An undercurrent of anger is bubbling in the crowd.

One man extols the benefits of the character protections on the sections surrounding his own. “We like the type of neighbours that character properties attract,” he says. Lloyd Macomber of Salmond Reed Architects laments what he sees as poorly designed townhouses springing up around the city. “My immediate thought about this is I’m coming to an age where I’m just going to scarper. I’m going to leave here,” he says. “Outta here. Gone.” Troy Churton, a member of the Ōrākei Local Board who has driven over from Remuera, is most aggrieved. “‘Affluent Nimby’ — that’s the easy thing that Remuera people get tagged with. There’s nothing frigging ‘affluent Nimby’ about this shit at all. This is intergenerational character they’re messing with,” he says, adding that character overlays “just make it a little bit more difficult for your typical developer to go in there and rape the place”.

Churton’s outburst doesn’t seem all that out of character — he once sent 150 emails and profanity-laced videos to the police complaining about the noise from their Eagle helicopter. But he isn’t alone in comparing desperately needed housing construction to violent sexual assault. Albert-Eden-Puketāpapa councillor Christine Fletcher made a similar comparison in a council meeting after the enabling housing bill was announced, saying the legislation was “tantamount to the rape of Auckland”. When asked to apologise, she amended her statement to something, if anything, worse. “It’s gang rape because it’s by both Labour and National and I am appalled.”

These character advocates face a fundamental problem: character isn’t explicitly protected in the NPS- UD, mainly because it’s a made-up category. It’s often conflated with ‘heritage’ due to its loose affiliation with architecture and history, but heritage is defined in the Resource Management Act, and has well-established criteria both locally and internationally. Buildings with heritage designations remain protected under the new housing legislation. By contrast, in planning terms ‘character’ is a council invention, and its parameters are vague. Even council planning committee chair Chris Darby struggles to deliver a concise explanation. “It’s groups of buildings, architecture that reflects periods of history,” he says. “It’s representative of areas. It’s architectural style that tells a story of the past.” Albany councillor Wayne Walker offers an even more wide-ranging interpretation: “It’s a whole lot of things and it’s going to vary somewhat from place to place.”

Caldwell is more succinct. “Vibes,” he says sarcastically, while pretending to flip through the council’s lengthy character descriptions. “Yes, the Auckland Unitary Plan has a section which gives the definition. Hold on, I’ll get it up. Specifically in relation to character, it’s vibes.”

Jeremy Hansen, a former editor of Home and author of the book Villa, sees some truth in the joke. He says most character homes are heavily renovated. Even those assessed as high quality are likely to have extensions. Some are just facades with essentially brand-new houses behind. Hansen says character areas have a kind of Ship of Theseus problem, retaining the shape of what was there originally, but lacking in historic components. “A lot of the special character values of these places have been corrupted by development, and in that sense, the character of those areas has been allowed to erode at the same time as protections have remained.”

Instead of genuine heritage, many housing advocates see character areas as a historical homage, similar to the former colonial streetscape exhibit at Auckland War Memorial Museum. Oscar Sims of the Coalition for More Homes calls them “the worst of both worlds” — cutting off intensification while failing to preserve either historic integrity or original built forms. Shane Henderson says they amount to “fake historical areas”. Wellington councillor Tamatha Paul (Ngāti Awa, Tainui) has proposed renaming them “colonial streetscape precincts”.

Architectural designer Jade Kake (Ngāpuhi, Te Arawa, Te Whakatōhea) says character areas are less about preserving history than protecting class. The rules governing them often restrict new development to lower densities than what already exists. Many of Auckland’s villas and bungalows were built before council planning rules — they’re close together, they shade each other, they’re on small sections. You literally couldn’t rebuild many of them under the rules designed to protect them, which enforce, among other things, height-to-boundary ratios, side set- backs and a 600m2 minimum plot size. Housing advocates see that apparent contradiction as proof that character areas are aimed at warding off new buildings rather than protecting old ones. Kake says the people defending those rules generally benefit from an inequitable status quo. “If they were living in insecure housing, or in really poor-quality housing, or if they were experiencing fuel poverty, and they’re trying to get across the city, or their kids were sick because they’re living in shitty homes, I think they might advocate a different position.”

Many character advocates would dispute that, saying their cause is more about preserving the “story of the past” advocated by Darby and others. But Auckland University doctoral student Emmy Rākete (Ngāpuhi) says that story is told through a Pākehā lens. Character rules generally cover villas and bungalows from the late 1800s to the early 1940s. Hardly any exist in the west or south of the city, where most Māori and Pasifika people live, and where the population is primarily poorer. In fact, when the Unitary Plan was passed, councillors opted not to instate protections on 2213 mana whenua sites, even as they extended character restrictions across most of the city’s best areas for development.

“Auckland is rubble, a lot of it,” says Rākete. “I can see a pā site from my window right now talking to you, and it’s rubble. There’s some really nice villas actually on the side of it. We’ll tear down the St James Theatre and do a really, really careful job cataloguing the Victorian rubbish that gets found underneath the stages, but there’s still concrete over people’s ancestors’ bones.”

The underlying accusations here are the same: ‘character’ is protecting an aesthetic beloved by many of the city’s affluent, predominantly Pākehā residents, rather than Auckland’s real history. In other words, vibes. Rich, white vibes.

Darby rejects that. “I’m not batting for special character on behalf of wealthy Aucklanders. I am not that person. Never have been. Never will be,” he says. “I’m batting for the special character — there’s a massive difference.” Critics say whatever the intent, the council is acting in the interests of wealthy homeowners in its intricately structured, tenuously legal response to the NPS-UD. To get around the lack of explicit exemptions for character homes in the section of the legislation referring to “qualifying matters”, it has relied on a catch-all subsection referring to “other matters”, which allows councils to protect houses for reasons including character provided they meet a higher evidentiary threshold. Those requirements include carrying out individual site assessments, justifying any restrictions on a site-by-site basis, applying the minimum number of development restrictions possible, and weighing those restrictions against what the legislation calls “the national significance of urban development”.

Sources inside the government say the council’s approach falls at the first hurdle. Its planners have invented a complicated system for assessing character as a qualifying matter, measuring every house in character areas against six criteria, including “level of physical integrity” and “architectural style”. If 75% of the houses within those council-defined borders earn a positive mark in at least five of the six council-invented categories, existing restrictions are retained. That approach ensures large numbers of poorer-quality houses are protected.

Concerns have also been raised over the fact the council has excluded houses at the rear of sections — often low-quality subdivisions — from its assessments, but included them in eventual development restrictions, citing a need to stave off “poor design outcomes”. In some cases it has grouped disparate, geographically separated houses together and assessed them as cohesive character areas. Transport and housing commentator Matt Lowrie estimates 10,000 more houses are covered by protections than would have been without these methodological quirks.

Scott Caldwell says Auckland Council’s approach amounts to “gerrymandering”. One high-ranking Labour source with involvement in enacting the legislation says the council’s methodology breaches the requirement to justify restrictions on a site-specific basis. He chuckles down the line as its approach is outlined. “I don’t know where they’ve dreamed this up,” he says. “It’s an elaborate construct that has no basis in the law. They’ve clearly put a lot of thought into it.”

Other experts are more confident the council is acting within the law. But even if it can defend its methodology, it will need to deliver compelling evidence that protecting special-character zones is more important than allowing development in the city’s most accessible central areas during a housing and climate crisis. Multiple planners, politicians and lawyers Metro spoke to say that will be its hardest challenge, and Darby and Tyler say they are still in the process of compiling a case for the restrictions.

They may struggle. Other than Devonport and a handful of others, Auckland’s character areas are also the places with the best access to public transport. They’re almost all within walking or cycling distance of the country’s largest employment centre. Auckland Council itself has declared a climate emergency and passed a climate plan, Te Tā- ruke-ā-Tāwhiri, which sets a target of cutting transport emissions by 64% against 2016 levels by 2030. The government has issued an Emissions Reduction Plan requiring large reductions in the number of kilometres travelled by cars and trucks. The easiest way to achieve those aims is to build apartments near jobs and public transport. Andrew Braggins says those factors and more make places like Ponsonby, Kingsland and Mt Eden the highest-priority areas for intensification, while special character is the lowest-priority qualifying matter in the legislation. “So you have this unbalanced seesaw, and Auckland Council seems to have made no attempt to weigh up that hierarchy as part of its assessment. It’s just gone about identifying every micro piece of character and sought to protect it, as if that has the same value as the intensification directive.”

Kāinga Ora has made a similar point, in slightly more reserved terms, in its submission on Auckland Council’s NPS-UD response. Under a section marked “special character”, it accuses the council of failing to justify its restrictions using the criteria set by the legislation. The submission says it opposes the reduction in development capacity. It’s been backed by Minister of Housing Megan Woods, who said in early June that the council’s “blanket approach” to special character is inconsistent with the rules governing qualifying matters in the act.

David Parker, the minister who could make the final decision on Auckland’s character areas, says he and his officials see the council’s approach as failing to comply with the NPS-UD. “We believe the special character exception they assert is too broadly cast both in terms of quantity and location,” he says. In essence, Parker says the council can’t stop dense development on 16,000 sites, many of which are near rapid-transit and town centres, while respecting the legislation’s call to weigh any restrictions against the “national significance of urban development”. “When you exempt that much in a quantity sense from the requirements, in terms of city centres and trans- port corridors, you’re going too far and you’re undermining the intent of the density requirements of the NPS-UD.”

Doorway, 1984

Despite several high-ranking government ministers and multiple ministries telling them otherwise, both Darby and Tyler insist the council’s approach is justified under the legislation, and in line with guidance issued by the Ministry for the Environment. In a series of exchanges with Metro, Darby initially admits one policy planner has told council officials their approach is non-compliant, but says “nothing formal has come in from the senior management”. In response to Parker’s objections, he says the council will make a site-specific case for their proposed character areas, and it’s “very mindful of the need to provide robust evidence”. When told Parker doesn’t think the scope of the council’s restrictions can be justified, even with that evidence, he stops responding for 19 days. Following Minister Woods’ comments, he noted her concerns, but added a rejoinder that he’s “surprised” she would say that to the media shortly before cancelling a quarterly meeting on the legislation between senior politicians and staff from the government and the council. He says neither minister has written to the council with their concerns. “I heard [about] Minister Parker’s lack of understanding of heritage versus special character and Minister Woods wanting us to pepper-pot zones where low-scoring sites are within identified special-character areas. I can deduce from that their opposition to our approach on special character, but it would help if they could articulate it like they knew their business.”

In response, a senior Labour source says it simply “beggars belief” that Auckland Council hasn’t “got the message”. The source says a PowerPoint presentation from a minister may be needed for the council to accept the government’s position. Tyler has painted her team’s approach as a compromise, telling Stuff she doesn’t think “anyone is going to be happy ultimately”. She’s sticking to that, saying officers have tried to balance character with allowing housing in climate-friendly areas. “I completely accept that point that in terms of intensification, building up — why wouldn’t we? This is a matter of trade-offs and choice, and I don’t think any city or region in New Zealand, including Auckland, has fully had the conversation with people about ‘What does a climate future look like in terms of our land use?’”

The council’s critics say it’s not compromising between two valid arguments, but rather bending or breaking the law to accommodate the types of people who turn up to Tuesday-night meetings at the bowling club in Birkenhead. The council is forging ahead anyway, mainly because Darby and many of his colleagues and constituents insist character is too important to lose. He runs through a list of cities that have retained elements of historic character, from Hamburg to Vancouver, before settling on Sydney’s rows of Victorian terraced houses, known as the Paddington flats. “Why are they not bowling the Paddington terraced housing? Why are they not? They don’t go and bowl that architectural fabric of the past to accommodate heightened density — to fit this more homogenous model.”

Sally Hughes, the chair of the Character Coalition, echoes Darby’s point. Even if they’re not in their original condition, character houses anchor a city to its past, she says. “It’s cultural heritage. And if we allow it to be degraded by allowing developments to go ahead that are completely out of character in those areas, it’ll be gone forever.” Her coalition’s website is replete with warnings about the impact of the NPS-UD. “These changes will have devastating impacts. Heritage values, the character of Auckland and our residents’ quality of life will be ruined or lost forever,” it reads, in reference to the possibility of three-storey housing.

But on the phone to Metro, Hughes strikes a more altruistic tone, saying she wants to preserve the city’s history for future generations. “What about when our children’s children say, ‘Where did all those lovely old houses go?’ And we’ll go, ‘We had to get rid of them’,” she says. “If we don’t protect it now, then future generations will never get to see [Auckland] the way it was.”

Fia Afitu remembers the way it was. She moved into her Ponsonby villa in the late 1970s. At the time, the city-fringe suburb was occupied by a large community of mainly working-class Pasifika families. A lavalava hung in the window of the house across the street. Hymns could often be heard echoing in choral harmony from the Tongan church down the road. Afitu hardly ever got to the end of a walk without getting into a conversation with someone she knew. “It was just vibrant. It had that Pacific Island sense of friendship. If you knew somebody and they walked past, they’d go, ‘Eh, how are you going?’,” she says. “There was that sense of community.”

It wasn’t long before real estate brochures started arriving in her letterbox. They talked up her house’s potential sale price. Agents rang offering free valuations. At their peak, the calls came almost daily. It’s not in Afitu’s nature to be rude, but she started getting short with the callers. “I kept on saying, ‘No, I don’t want to’. They kept ringing. In the end I’d just say, ‘No, not interested, bye’.”

Some of her neighbours weren’t so determined. They sold up and moved west or south. Afitu remembers the whispers going around at church. Families would return home and gossip over lunch about the latest people to join the exodus. Quickly the area was transformed. More expensive shops went in on the main street. The villas started getting painted in whiter shades of beige. The lavalava came down from the window across the street. These days, Afitu doesn’t stop to talk to so many people on her walks. “Everything’s changed now,” she says. “And I can’t bring it back. Sometimes you wish that it could be protected but of course you can’t. It’s done.”

Afitu’s neighbours were driven out mainly by housing scarcity. In the 1970s, a process of so-called “urban renewal” was taking place in Auckland’s centre. Manufacturing jobs moved out of the area into south or west Auckland. Hundreds of houses in suburbs like Ponsonby were demolished or converted to professional offices and light industry. White-collar workers, drawn by the promise of escaping growing congestion on the city’s newly built motorway system and living closer to their offices, competed for increasingly scarce residential space with the area’s less-affluent resident community. Working-class renters were the first to be priced out. Many Pasifika homeowners went as well. The calls from real estate agents kept coming.

These days, the housing scarcity that forced many Pasifika residents out of Ponsonby is mandated by the council on character grounds. The suburb’s combination of constricted development and desirable location has made it into one of the most expensive places to live in the country. A few years ago, the house behind Afitu’s property sold for more than $4 million. She sometimes hears from former residents of Ponsonby and Grey Lynn. Most are now dealing with difficult commutes, spending hundreds of dollars on fuel driving in from Papakura, or taking 50-minute bus rides down to Te Atatū Peninsula. Their families left the city fringe to make way for richer new residents or to escape rising costs. Now they’re kept out by a council flailing desperately to ensure that the kinds of walkable, accessible lives it trumpeted in 2016 are mostly reserved for the city’s most affluent citizens. The former residents often say the same thing to Afitu: “I’d like to move to where you are, but I can’t afford it.”

Evening Door, 2002

In statements to the media, Auckland Council has insisted that character areas “maintain a sense of history and place” in older residential suburbs. But the history of Ponsonby and other character areas is told in the stories of working-class people trying to get by and build a life. Emmy Rākete sees something perverse in a council seeking to maintain a “sense” of a more egalitarian past with rules that ensure it will never exist again. “If we want to preserve and honour this history of providing housing for working-class people, we should be providing housing for working-class people,” she says. “Instead, we’re trying to turn the urban core of our biggest city into a historical preserve.”

Peter Nunns, director of economics at Te Waihanga New Zealand Infrastructure Commission, says character areas are part of a 50-year history of council development restrictions that have put homes out of reach for many Aucklanders. “They’re essentially a continuation of 1970s district schemes which cut capacity for growth,” he says. “So the predecessor to the special character area policy has really been at the heart of our housing affordability crisis.” Character advocates say even if you built apartments in places like Grey Lynn, they’d likely be expensive. Nunns says a large body of international research shows all new housing supply helps affordability, including at the more luxury end of the market, and high land values in character areas indicate a huge amount of constrained development potential.

He has local stats to back that up. His research demonstrates house prices nationwide would be 69% lower if it weren’t for council-enforced density limits, along with the resulting inefficient, car-centric layout of our cities. When it comes to Auckland, though, Nunns’ interest is personal. His great-grandfather built some of the villas in Ponsonby and Devonport. “So, from a family taonga perspective, I can see the appeal of this connection with the past.” Nunns doesn’t let that define his views on developing those areas, however, because he knows his great-granddad wasn’t trying to build wooden monuments for generations to come; he was trying to meet his family’s needs. People who want to set down roots today deserve the same opportunity, he says. “If I told my ancestors we can’t meet our current housing needs because we’re protecting what they built 100 years ago, I suspect that their answer might be that we’re missing the point.”

Peter Siddell’s paintings appear thanks to the Siddell Estate, Artis Gallery, Art + Object and Warren Olds.

Cover image: Evening Cloud

–

This feature was published in Metro 435

Available here in pdf format.