Oct 19, 2017 Urban design

Despite funding hiccups, a long-awaited pedestrian and cycling path across the Waitemata represents a new urbanism.

This year, Downer Construction, the builder, withdrew from the PPP, saying the price wasn’t right. That led to the SkyPath Trust, which created the project and has toiled for over a decade to make the vision a reality, also pulling out. At the time of writing, the council was persisting with the PPP to construct the facility. The spanner in the works is that the trust recently told councillors its withdrawal means “the PPP does not have the right to use the trust’s intellectual property for the design, engineering and development of SkyPath”. The trust, no longer a PPP proponent and lobbying for funding from the next tranche of the Urban Cycleway Programme, is now determined to make the project toll-free.

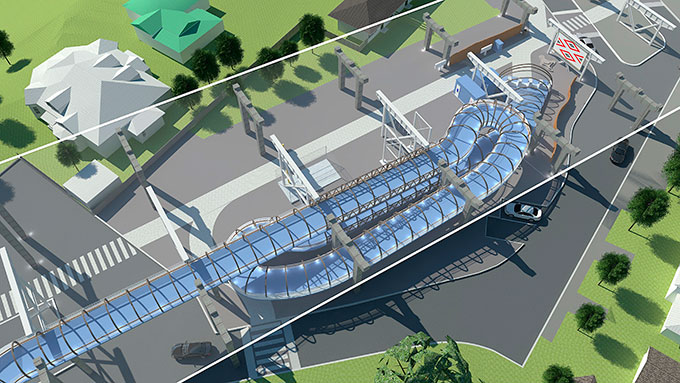

View a fly-through of the proposed design:

While the government remains non-committal, Labour has announced that, if in government, it will provide $30 million to deliver a toll-free SkyPath.

Despite the fiasco, the pedestrian and cycling harbour crossing is still terrific. It heralds a change that echoes the opening of the Harbour Bridge in 1959. The bridge was the epitome of the new Auckland, a city boldly expanding and embracing an automobile future. With SkyPath, the bridge gets its promised missing footpath, discarded due to cost cutting. It also celebrates a new urbanism, a city that has at last decided to be driven by something other than the car.

By far the most important aspect of SkyPath is that it’s a public good. Potentially, it provides access to cross the harbour for all, disrupting the social disadvantage of only being able to cross in a car or bus. Which is why it ought to be toll-free and why the government ought to step in. Where else in the world do pedestrians pay to cross a bridge and cars go for free?

Auckland can be so stupid. There’s the chance to create something magnificent for the city, a truly public space with a view to die for. Why does Auckland so often end up with something half-arsed? SkyPath promises to be symbolic of what it actually means to inhabit a liveable city but the prospect of a lingering shortfall in expectation looms. As some of the design constraints show, SkyPath is complex, but it’s still possible to do it right:

It can only be under the southbound lanes.

One of the long-running debates about SkyPath has been the bridge’s load capacity and protecting its structural integrity. The genius of SkyPath is the discovery of spare capacity courtesy of the heavy goods vehicles that leave the port fully loaded and travel north. On the return journey, the trucks are mostly empty, so the southbound lanes can take more loading. Brilliant.

It can only be 4m wide.

Tucked under one of the clip-ons added to the bridge in 1969, this is all the width there is. That means cyclists and pedestrians will have to share the path, which is not ideal. But with careful design to limit cycle speeds, it’s possible to make this safe. At the bridge piers, the space bulges out 2m, creating a viewing area. There’s scope to make this better. The earlier design by Copeland Associates had several more generous viewing areas accessed by descending below the path to pause and take in the vista. Clever. If SkyPath is to be a world-class tourist destination, this aspect of the design needs to be world-class.

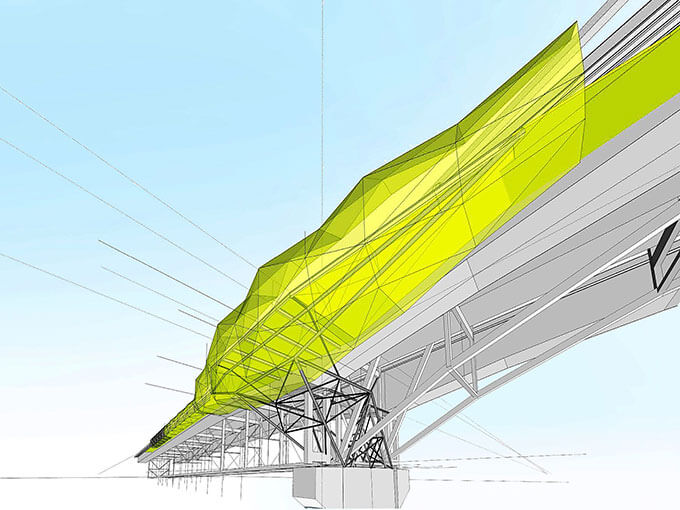

Lightweight construction.

To protect the structure of the bridge, SkyPath has to be as light as possible. With new composite materials, we have the technology. But the high-quality carbon-fibre stuff can be terribly expensive. Cost considerations could compromise making SkyPath out of the best, most long-lasting, robust materials possible. Let’s hope quality wins.

It will be quite lively.

The bridge moves. It’s designed to. Much thought has gone into pedestrian vibration, especially how to avoid a resonant response as happened during the Maori Land March in 1975 when the bridge developed an unnerving sway. The narrow path and the control of the live pedestrian load by turnstiles at either end mean that’s unlikely to happen. Just in case, the engineers have proposed three water-filled, liquid-tuned dampers. The walkway isn’t a closed tunnel, but will be open to the elements via some sort of mesh exterior, so walkers will also feel the outside.

It is not a public space.

One of the consequences of the bitter Environment Court battle waged by some Northcote residents is that the hours of opening are 6am-10pm. It will also be run by a private company to collect tolls, and will have guards and CCTV to keep everyone safe. Ideally, SkyPath should be a true public space, open 24 hours, for use by everyone. Cars have this right on the bridge; so should pedestrians.

It is part of something much bigger.

While getting across has been the raison d’être of SkyPath, the bigger idea is where you go next. SkyPath, linking with the New Zealand Transport Agency’s proposed SeaPath from Esmonde Rd to the bridge, connects pedestrians and cyclists to the whole city, opening up a grand traverse — Esmonde Rd, Takapuna, Devonport, Westhaven, Tamaki Drive and much more — that really will make Auckland great for commuters, tourists and recreation.

It is a heritage structure.

Let’s face it, “the coathanger” is no Golden Gate. But it does represent a piece of engineering heritage. This has affected SkyPath’s design. Anything attached mustn’t detract from the bridge and mustn’t be too visible; ideally, it ought to be camouflaged battleship grey. The resource consent has allowed a bit of colour (white), but overall the design is backward about coming forward. There’s also a ran-out-of-money feel about the landing ramps at either end. And the suggestions of public artwork seem like a tacked-on afterthought.

SkyPath is an opportunity to enhance heritage in a spectacular way — to celebrate the return of the long-lost path of the original bridge design, to create a 1km-long flamboyant artwork. To honour a pre-European crossing point. To pay homage, as some have suggested, to the legendary taniwha Ureia residing in the reef below Pt Erin, metaphorically rising up for the people. To light up the city with a symbol of connection.

This is published in the September- October 2017 issue of Metro.