Dec 20, 2019 Urban design

The station designs for the City Rail Link have just won an international architecture award. They’re an example of a major shift under way in Auckland — in which Maori design principles, sustainability, and new attitudes about ‘bicultural’ design are changing the shape of our city.

The City Rail Link (CRL) — New Zealand’s largest infrastructure project — is an essential investment in Auckland’s urban future: a long-overdue intervention that gives us a shot at having a public transport system that is at least passable by international standards. It’s like a quadruple bypass — a way to clear the daily snarl-ups on our archaic, clogged urban arteries, and get the city’s lifeblood moving.

For the past several years, CRL has also been the launch pad for some of the most ambitious design thinking in Auckland’s recent history. The four stations we will access the CRL through — an upgraded Britomart (likely to be renamed Waitemata), a much-expanded Mount Eden (Maungawhau), and the new stations, Aotea (in the CBD) and Karanga-a-Hape (on Mercury Lane) — represent transformations not only in our transport infrastructure but in how we think about public architecture, its storytelling and place-making functions, and its potential to embody a set of bicultural values that, so far, have eluded the designers of many of our most significant building projects.

The station plans have brought together some of Auckland design’s most serious players: architects at Jasmax (working alongside the international firm Grimshaw, as an embedded team at CRL’s offices); one of our most important Maori architects and design thinkers, Rau Hoskins, of designTRIBE; and a team from Alt Group led by Dean Poole, who were instrumental in developing the concepts, material languages and unique identities for each of the stations. But the essential piece of the jigsaw was the involvement, from the very start, of eight mana whenua groups from across Tamaki Makaurau.

“The structural relationship that was established at the outset between mana whenua and CRL was critical,” says Hoskins. “You can’t have a good process unless that first principle, that mana principle has been well handled. Mana whenua have got lots of demands on their time, and they quickly work out which groups are really genuine and valuing their inputs, and others who are perhaps a little more superficial with their commitment to their involvement.”

Matthew Glubb, a principal at Jasmax, agrees: “For us, it’s one of the few projects where we’ve seen the engagement with mana whenua happen right at the start of the project,” he says, “which has allowed us to build in the concepts, the values, the beliefs into the architecture from Day One.”

The quality and consequences of that dialogue has recently been recognised internationally: the CRL project won the award for Cultural Identity at the 2019 World Architecture Festival (it’s also shortlisted for the Infrastructure Award, which will be announced this December in Amsterdam). Seeing the 3D renders and fly-throughs of the stations, it’s easy to see why: collectively, they represent a rare moment of architectural ambition by Auckland Council standards — aspirational, functional, open and beautiful.

The common story to all the stations is of Rangi and Papa, the sky and the earth being forced apart to open up the world. It’s a particularly apt physical metaphor, given these stations are literally where we will enter the whenua. This is given form in the new Aotea and Karanga-a-Hape stations by pairs of interlocking boxes: a soft, light facade of horizontally-suspended acrylic rods for the upper block, and earthbound materials such as stone for the bottom.

Each station also has its own atua or deity: Tangaroa for Britomart/Waitemata (the god of the sea — Britomart is land reclaimed from the harbour); for Aotea, Rongo-ma-Tane, the god of cultivation, alongside Horotiu, the taniwha who guards Waihorotiu — the stream that once ran where Queen Street now is; Tane-mahuta for Karanga-a-Hape (who forced his parents Rangi and Papa apart); and Mataoho at Maungawhau, the local deity for volcanic activity.

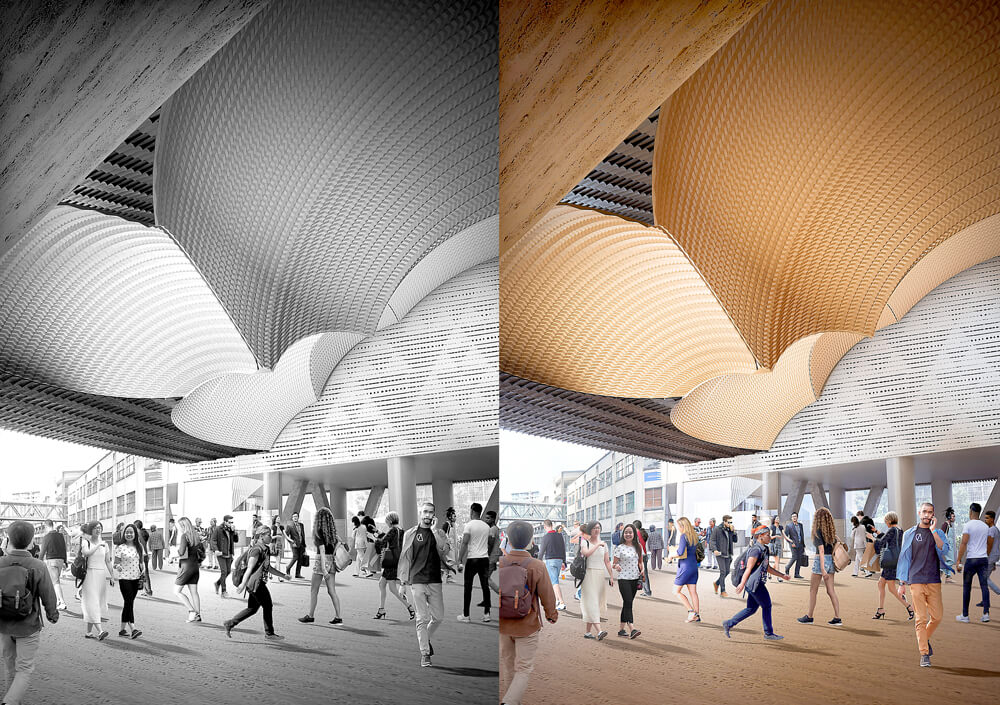

Each station also has its own unique threshold, the design of which, led by Alt Group — working closely with Jasmax’s architects and mana whenua — shows the firm at its singular, visionary best. At Aotea, a huge ceiling of hanging rods will create the undulating effect of flowing water, as well as suggesting raupo (bulrush) growing along a river’s edge; at Karanga-a-Hape, a carved and vaulted wood ceiling will create the negative silhouette of a kauri canopy — evoking Tane-mahuta — while tiles on the walls down to the train platforms will crimp and peel like a kauri’s bark. And at Maungawhau, the main motif is carved circles and swirls that evoke the nearby volcanic cone, its kumara pits, and the lava flows that made the Auckland isthmus.

For Alt Group, working on the stations with Jasmax was an unmissable opportunity to help shape an expression of Tamaki Makaurau’s identity. “You can change the way you think of a city forever through a transport system,” Poole says. “When we think of London, we think of the Underground, when we think of Paris, we think of the Metro. And they’re an expression of the identity of the time. So art deco is manifested in parts of London. Art nouveau is expressed in parts of Paris, and they did that because they were trying to convince Parisians to go underground, by using the design language of the day. Why would we be any different? Which is when you ask, well, how do you pick a design language that is enduring? And that’s the bit where you go, it’s not about a personal narrative, it’s about a collective narrative.”

For Hoskins, this ties directly into what he’s been pushing for 25 years; that instead of pursuing a generic internationalism, New Zealand architecture should find its distinctiveness in a meaningful engagement with Maori forms and values. The challenge in the past, he says, has been how to get mainstream architecture firms to understand those values and their potentials — rather than just slapping a bit of kowhaiwhai or tukutuku onto a facade, or commissioning a Maori artist to make something for the foyer.

This is what makes the CRL stations game-changers: because Maori values and narratives are embedded in the forms and materials of the structures themselves, rather than added on as surface decorations. The involvement of mana whenua has obviously been vital to this. But their input, and its consequences, can only be fully understood in relation to the Te Aranga Maori Design Principles — which, as they begin to be rolled out at scale, are starting to feel like the shift New Zealand architecture has long needed.

The development of the Te Aranga principles was led by the Nga Aho network of Maori design professionals. In 2005, the Ministry for the Environment formulated its Urban Design Protocol, but was criticised for its lack of consultation with Maori. So, in late 2006, a group of leading Maori design thinkers met at Te Aranga Marae in Flaxmere to come up with a response. The eventual result was the Te Aranga Maori Cultural Landscape Strategy — a radical new way of thinking about how to ensure a meaningful Maori presence in our urban environments.

The seven Te Aranga principles include mana (the status of iwi and hapu as mana whenua is recognised and respected); whakapapa (Maori names are celebrated); taiao (the natural environment is protected, restored and/or enhanced); and ahi ka (iwi/hapu have a living and enduring presence and are secure and valued within their respective rohe).

The most important feature of the principles is their practical applicability: it’s clear how they can be turned into design action. And Hoskins says that was entirely intentional.

“We wanted them to be digestible by the mainstream design community — architects, landscape architects, urban designers,” he explains. “We wanted them to be practical, because prior to Te Aranga, people had variously talked about just applying Maori cultural values. So you talk about kaitiakitanga, manaakitanga, kotahitanga, wairuatanga. But when you talk to a mainstream designer about wairuatanga, they go, uhhhhh…….”

Instead, with Te Aranga principles like ahi ka — a living presence — he says designers can have tangible conversations with clients and mana whenua about what that looks like in a specific building, space or place.

Auckland Council has since incorporated the Te Aranga principles into the Auckland Design Manual, and CRL was the first major opportunity to put them into action. As Jasmax’s Elisapeta Heta explains to me, the adoption of the principles is quickly reshaping the way many of our leading architectural practices think about their work. Heta is part of Jasmax’s Waka Maia team of Maori designers, and within the past five years, she says, the conversation, at Jasmax and other mainstream firms, has shifted hugely.

“We [Waka Maia] have gone from being a nice-to-have on significant projects, to asking whether it’s something that needs to be in absolutely every project in the office. I can hand-on-heart say most practices now are having to think about this, particularly if they’re working in the civic or public space, or with universities, because everybody’s waking up to what their treaty obligations might be. And that’s really exciting, but really difficult in a country that hasn’t taught New Zealand history very well.”

Heta is an example of an emerging group of younger Maori designers beginning to make their presence felt in Auckland, both in firms like Jasmax and in wider conversations about urban planning and design. This is especially important for a field that had been so dominated by Pakeha designers, and for such a long time. A quick scan through the lists of principals and associates at most of our major firms shows there’s still an almost-laughable bias towards Pakeha men, mostly aged between about 35 and 50. But there are signs that things are beginning to change.

Hoskins says the architecture schools have a major role to play here, and that they’re slowly improving their cultural capacity (even if they have a long way to go). But the key change, he says, “has been that we’re getting graduates who have come into their studies with more cultural knowledge, and been more demanding of their schools of architecture, and then of course emerging as graduates with more confidence and greater ability to engage effectively with mana whenua on these projects.”

The profession’s accrediting body, the New Zealand Institute of Architects (NZIA) has also recently stepped up and recognised its Treaty responsibilities. In February 2017, it signed Te Kawenata o Rata: an agreement with Nga Aho that formalises a relationship between the two organisations as treaty partners, and ensures representation of Nga Aho on the NZIA’s council.

For many younger Maori designers, the significance of Nga Aho and its support has been essential in their ability to see themselves working in an industry which, as Heta says, has been built largely around the singular, Western, “architect-as-genius” model. The Te Aranga principles provide a very different working framework — a space for meaningful collaboration, in which “mana whenua are being given really key and important opportunities to actually co-design their own city”.

For the designer and writer Jade Kake, this squares with the kind of architecture she wants to practise and see more of, which is “about being in service of communities, and supporting those communities to live in ways that they want to live. That aligns with culture, aligns with living well, aligns with looking after the environment — all of those things.”

In October, Kake published Rebuilding the Kainga: Lessons from Te Ao Hurihuri: a BWB Text that draws both on her research and her own whanau’s experience of planning a papakainga housing development. It’s a thorough, pragmatic and progressive take on the Maori papakainga model of whanau-based living. It also discusses the ways in which it could become part of the solution to New Zealand’s biggest urban planning challenge: the provision of affordable housing.

Kake defines papakainga in her text as clusters of dwellings occupied by whanau or hapu and associated with shared natural resources (“papa” refers to the Earth, Papatuanuku), where the exchange and distribution of goods and services is regulated by tikanga.

For Maori, papakainga were long-standing ways of building, maintaining and sustaining communities until colonisation — and in particular, the vast alienation of land as a result of the 1862 Native Lands Act — dismantled those communities and placed the land they once occupied within a Western framework of land title.

“The defining feature [of papakainga] is probably connectedness,” Kake tells me, “to one another and to the environment. And I think that’s reflected in the ways people live their lives, the ways they share resources, the ways they use resources — even things like energy and infrastructure. I think the difference [from European models of communal housing] is tikanga Maori, and the ways these spaces might be used and the relationships might be different because of that whakapapa connection, and cultural practices.”

This, she argues, can begin to address inequities that see Maori suffering under some of our worst housing statistics, and build healthy, sustainable communities connected to the land. Hoskins also believes the kainga model can contribute to better housing outcomes for Maori.

“It starts with the land,” he says. “It’s accepting that the land is held in some sort of communal ownership, and that the whenua sustains us — it’s not something that we seek to own in ‘fee simple’ terms… What our research shows, and what my work has picked up on over the past 25 years, is that if Maori have a secure connection to that land and a strong association with the ownership structure of that land, then it’s not about home ownership. It’s about connectivity and security of tenure.”

Many councils around the country already allow for kainga developments on jointly owned Maori land. But even with these regulations in place, Kake says financing such developments is a huge challenge — precisely because the communal way they’re owned and built doesn’t fit neatly with that “fee simple” model of ownership, which conventional mortgage finance depends on. The government, via Housing New Zealand, does underwrite a Kainga Whenua Loan Scheme. So far, though, Kiwibank is the only bank to offer it, and it comes with fairly restrictive conditions.

Kake has become increasingly interested in how European co-housing and co-operative models might offer potential solutions to these financing difficulties — enabling whanau members to essentially be shareholders in a co-operative that leases land from the entity that owns it. It seems both an irony and a huge opportunity that Pakeha millennials in our cities are starting to look seriously at such options too, as a way to counter runaway house prices. I ask Kake whether papakainga, though obviously applicable to Maori-owned land (usually outside major centres), could really be a practical solution for urban situations, where housing intensification is going to be essential.

“I think Urban Development Authorities are the key here,” she answers, “because they’re responsible for major urban regeneration projects, with a lot of master planning and a lot of power and control. If that’s applied in the right way, I think we could radically shift social outcomes through design. At the highest level there needs to be that commitment of partnership with mana whenua. There also has to be a commitment to rethinking our settlement patterns. So rather than just laying out another subdivision with the same individual lots… this is a unique opportunity to do something different.”

The Labour-led government has recently recognised that “something different” has to happen, with the establishment of Kainga Ora — a massive overhaul of its urban development policies and an attempt to overcome the early disasters of KiwiBuild. The new structure aims to place mana whenua at the heart of decision-making and design processes.

But, as the designer and researcher Jacqueline Paul points out, there’s a long way to go. For the past 18 months, she has been researching the applicability of Maori housing models, particularly as they relate to rangatahi Maori in Auckland. “The young people we’re working with just don’t see themselves buying a house any time soon,” she says. “That’s just the reality; we can’t afford it.”

I ask her whether — despite all its failings — KiwiBuild has had any impact, either on aspirations or on actual rates of Maori ownership. The problem, she points out, is the one many commentators have criticised KiwiBuild for — its “affordability” measures. “Maori still [earn] half of what non-Maori make,” she answers. “So income is an issue, because that’s how affordability is measured. So we will continue to be marginalised and disadvantaged because the policy isn’t targeted, funding isn’t targeted.”

One successful recent development Paul points to is Waimahia Inlet, where around 50% of the owner-occupiers are Maori and Pasifika. This, she says, is partly down to a rent-to-buy scheme, which puts ownership more in reach of middle-to-low income earners.

Waimahia, on he Weymouth Peninsula near Manurewa, was developed by Nga Mana Whenua o Tamaki Makaurau — Tamaki Collective: a group of 13 Auckland iwi and hapu, working alongside other not-for-profit community housing groups. So once again, the success of the scheme seems to have been the result of having mana whenua involved at a high strategic level, right from the start.

The Te Aranga principles are going to play an essential part in such developments. In 2017, Paul wrote a paper that looked at their applicability in the context of the Tamaki Regeneration Project. Some examples are the ways in which the principle of whakapapa can be observed through the correct use of ancestral names, signage and wayfinding, and ahi ka can be observed by ensuring that mana whenua are involved in design decisions, in maintaining and protecting natural features like waterways, and planning community events and activities. Tohu — in which features of the landscape and their cultural significance is acknowledged — can be addressed through the siting of buildings and the creation of views that establish connections with maunga, rivers, and so on. Kake has a similar approach in her design practice, thinking about the siting of buildings, their relationships to landmarks, and native planting as ways to integrate Maori values without introducing them through decorative afterthoughts.

The cost, when it comes to housing developments, of getting engagement with mana whenua wrong, can be seen in one giant, knotty Auckland example: Ihumatao. Several people spoken to for this story pointed to the situation there as being a massive failure of process — of not consulting with mana whenua sufficiently, or not actually consulting with the mana whenua most directly affected by Fletcher Building’s proposed housing development there.

The best writing on Ihumatao has been a series of excellent columns by the historian Rawiri Taonui, for Waatea News. Taonui’s analysis leaves absolutely no doubt as to who he believes is responsible for the mess, and, consequently, for cleaning it up: Fletcher Building, Auckland Council, and central government. Auckland Council, Taonui argues, are culpable because they designated the disputed land at Ihumatao a potential Special Housing Area, without adequate consultation with all the mana whenua groups affected. This recommendation was then gazetted by the National Government, and when some Auckland councillors later tried to reverse the decision, Nick Smith, as Housing Minister, dug his heels into the rich, volcanic Ihumatao soil.

Taonui describes this as a series of events carried out with “indecent haste” and a “disdain for the Ihumatao community”. And his analysis raises an important point when it comes to the question of what a genuinely bicultural approach to housing and urban planning looks like. The great housing panic of the past few years — resulting in policies like Special Housing Areas and KiwiBuild — often resulted in the rights of mana whenua, as treaty partner, being minimised, incorrectly observed or overlooked altogether.

Alongside the history of confiscation, the Crown and council’s legacies of environmental exploitation and degradation at Ihumatao are utterly egregious: the quarrying of the maunga; the loss of land for the airport runway; and the building of sewage treatment facilities that devastated the shellfish beds and fishing grounds of the Manukau Harbour. As Taonui puts it in one of his columns, “Auckland has a history of shitting on Maori”. Literally.

Hoskins points out that no developers were interested in Ihumatao until the oxidation ponds were removed and the coastline was revealed. He also says that an innovative, regenerative new approach there, including medium-density housing following kainga principles, could be transformational. But again, central government and council can’t shirk their responsibilities. “I think there’s a great opportunity for the government to not only be part of the solution for the disputed whenua,” he says, “but also to turn its attention to comprehensive support for the community aspirations of Ihumatao residents.”

Those aspirations are as much about the state of the land as the land itself, and this is another space where the Te Aranga principles could come into their own: sustainability, and environmental regeneration.

Around the world, and especially in the South Pacific, climate change is hitting indigenous populations particularly hard, including Maori. “We’re going to be under water if we don’t get our shit together,” Jacqueline Paul says. “[Forget] all the political and bureaucratic bullshit — it’s like, we’re going to be under water, you’re going to lose your homes, you’re going to lose everything. For us [as Maori], if we lose our land, we’re going to lose our identity. We’re going to lose our ancestors, who are buried in urupa. Our marae are going to be flooded. So this is the reality: in order for us to survive as a people, we need to be working together to seek climate justice.”

Elisapeta Heta puts the connection between Maori values and the environment eloquently.

Kaitiakitanga, she says, “is not a substitute for the word sustainability. All the ‘tangas’ are a system or a method of understanding the world. The thing about indigenous value systems is they don’t premise human experience as being above or over other things. The pure fact is when you’re truly talking about the depth of Maori values and ideas, this includes the environment without having to point it out; it’s implicit.”

This, in the end, might well be the deal-breaker for mainstream architecture’s adoption of the Te Aranga principles. Globally, architecture has one hell of a mea culpa on the way, in that our built environment contributes massively to carbon emissions, both in the embodied energy of building materials and in the inefficiencies of buildings themselves. The industry has known this for a long time, and is now scrambling to change.

“The obligation for us as designers shaping a city is obviously to create sustainable places — healthy, happy places for our communities and the cultures and groups within them,” Matthew Glubb says. “The bicultural framework gives you a unique mana whenua view of sustainability, and a world view that places people and nature in the same space, as an interconnected whole. It’s also strongly related to place-making, which is recognising or valuing and responding to those cultures.”

This is one of the most intriguing aspects of the CRL station designs: their attempt to bring together an international trend towards “biophilic” design — designing from nature, using sustainable materials and local narratives in an integrated way — with the specifics of the Maori worldview as framed by Te Aranga, within the context of the climate crisis.

When I suggest to Hoskins that in this thoroughly 21st-century triangle we might find new architectural forms unique to New Zealand, he agrees, but with one note of reservation. “As architects, we’ve got the power of being specifiers [of building materials],” he says. “But we also have this fourth element in the room, which is that it costs an incredible amount to build in Aotearoa. And we’ve got clients who balk at paying 20 to 25% more for the construction. That’s going to be an ongoing challenge.”

There is also the danger, given New Zealand architecture’s ongoing diversity problem, that this growing use of Maori design and its sustainability credentials becomes a way to feather ambitious Pakeha caps rather than bring about meaningful structural change.

“The question that I always ask is ‘who is sharing power and resources?’” Kake says. “Where is your commitment to re-investing in those communities, and investing in Maori practitioners? … Building capacity and capability within communities, and engaging their own people on projects, in whatever way is appropriate, is really important.”

To be clear, there are still blandly internationalist glass towers going up in Auckland. There are still plenty of housing projects around the city led by profit-driven developers who don’t give a toss about Te Aranga design principles or sustainability obligations, beyond what their resource consents demand. But those might be the last examples of a way of being, and building, that has had the run of things for too long, and already left too much of its colonial mark on our built environment.

We’re not quite witnessing a revolution, yet. But there’s a clear shift under way. And if it keeps on its current trajectory, it could dramatically change how we all experience and understand this city — and who gets to shape it.

This piece originally appeared in the November-December 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline ‘Station to station’.