Oct 26, 2017 Urban design

One of central Auckland’s oldest thoroughfares tells a bigger story about our city.

In Auckland we found a one-bedroom flat in what was once an old clothing factory owned by Ross and Glendining Ltd, a Dunedin firm. A friend’s mother used to work here as a machinist when she was a teenager. It was converted into expensive apartments in the 1990s and renamed ‘Park Lane’; the duplexes on the roof have terraces overlooking Myers Park. An old school friend, whose parents live downstairs, calls it an old people’s home because so many of the residents are elderly.

It’s on Greys Avenue, one of central Auckland’s oldest roads — known as Grey Street until 1927. It’s steep and straight, climbing from behind the Town Hall to Pitt Street and the Karangahape Road ridge. In the past it reached all the way to Queen Street and was a busy route for horse-drawn carts.

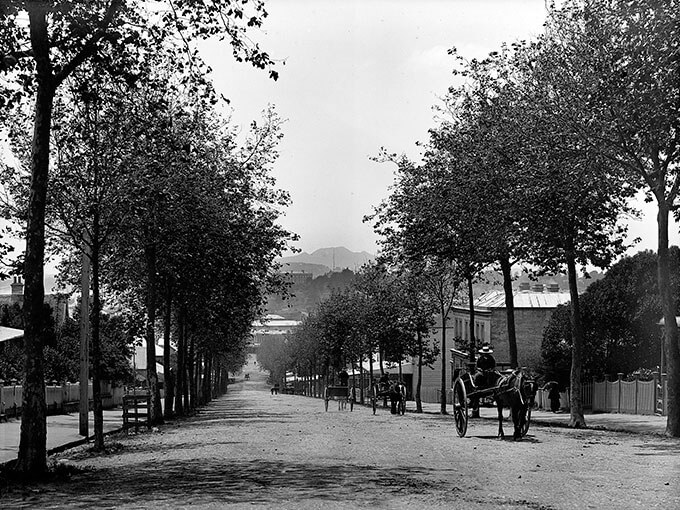

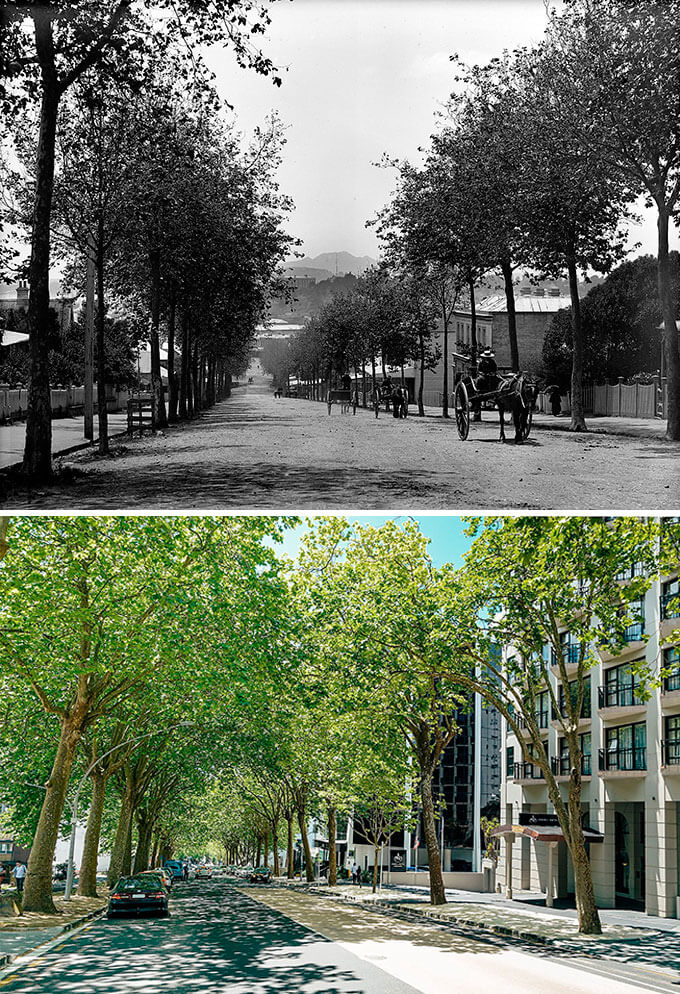

The London plane trees that line it were planted in 1871, part of the city’s first beautification project. Streets like Jervois Road in Herne Bay were stripped of many trees by some subsequent ruthless and short-sighted regime hell bent on wider roads. But the Victorian plane trees here still flourish, a skeletal arch in the winter, a lush canopy of green in the summer.

We wanted to live here on Greys Avenue because the flat has a four-metre stud and a long stretch of wall in its main room, ideal for our battalions of books. The location means we save on bus fares: Queen Street is just down the hill, K Road just up. I can climb through Albert Park to my job at the university. We can walk to concerts at the Town Hall, events at the Aotea Centre and the Civic, plays at Q and the Basement Theatre, Unity Books, movies, record shops, Burger Fuel.

For me there’s something else as well, something about inhabiting part of the city’s past. Sometimes the city’s past is more clear in my mind than its muddled present. I still think of the cafe at Smith and Caughey’s as the Copper Kettle. I still think of Beresford Square as the place where the Farmers free bus stopped and turned. Because I lived away for so long, I missed many of the gradual changes of Auckland. I wasn’t here when the old houses on the Queen Street side of Myers Park were demolished and apartment towers built in their place. I wasn’t here when the Civic was under threat, or the Town Hall. I wasn’t here when the flagship Farmers building on Hobson Street closed. The Farmers, my grandmother always called it — short for The Farmers Trading Company. When she took me on the trolley bus along Ponsonby Road to do the daily shopping, we were going to The Three Lamps. In the 50 years since I was born, Auckland has busied itself getting rid of trees, Victorian buildings, grand department stores, art deco theatres and definite articles. In 2016, the 1920s dance hall on Queen Street that housed Real Groovy Records was demolished.

This part of the city has strong family memories — which means the memories are not just mine. My father used to deliver the Herald on a route that included Franklin Road and Wellington Street. When he collected the money due, he’d come to Greys Avenue, to one of the Viennese-style state flats built in the late 1940s, and hand it over to a Herald employee. Everyone wanted to live in those stylish new blocks, he said. In those days, our building — right across the street — was still a shirt factory.

In the late ’40s, my father’s Uncle Bob and Auntie Alice were working in another shirt factory on Karangahape Road. He was a shirt-cutter and she was a machinist. My father attended the Campbell Free Kindergarten in Victoria Park, Beresford Street School, and Seddon Tech on Wellesley Street. Before he became a printing apprentice at the Herald, he was a St John Ambulance driver, spending overnight shifts in the old brick Central Fire Station on Beresford Square.

My grandparents lived on Anglesea Street in Ponsonby, moving in the 1950s to a double-fronted kauri villa — large, cold and creaky — on the corner of Ponsonby Road and Douglas Street. When I was a small child, Granddad worked as a storeman at the Herald. Every year, on the day of the Farmers Christmas Parade, he would guard a parking space on Wyndham Street for us. Grandma managed the staff cafe at Rendells department store on Karangahape Road. My Auntie Dawn began her long retail career selling gloves in George Courts, a few doors down from Rendells. After my brother broke a leg off my Barbie, she was sent to the Dolls’ Hospital further along the road. The Thursday nights of my early childhood were spent going late-night shopping on K Road. It seemed bustling and exciting to me, especially the clanging cage lift in George Courts, though I could have done without the pungent-orange Hare Krishnas, whirling their way down the footpath: they put me off incense for life.

Now my students complain about the gentrification of K Road: it must be stopped, they say — en route from an art gallery opening to a poetry reading. But K Road was already gentrified a century ago, when its sturdy blocks of shops, its tea rooms and arcades were built. The decline of K Road began during my childhood, as new suburbs drained the city.

We moved to West Auckland and eventually traded Thursday late-night shopping on K Road for Friday late-night shopping at LynnMall. It was fresh and shiny in the 1970s, open air and Hare Krishna-free. But during its inevitable decline it looked even more tawdry than K Road, without any art deco character to redeem it. Now the mall is fresh-faced again, with new cinemas and a transport hub; a restaurant quarter called The Brickworks has opened, nodding to the neighbourhood’s past as Crown Lynn Central. The whole suburb of New Lynn is being gentrified. You can tell, because apartment blocks are going up and the restaurants in The Brickworks are referred to as ‘eateries’.

My father said that the shirt factory where my Uncle Bob worked was above the old Rising Sun Hotel on K Road. My father also said that a Chinese restaurant on Greys Avenue, just down from where we live now, was notorious for stealing and cooking cats, so I think my father was not an entirely reliable witness. But he did remember when Greys Avenue and all the long-gone small streets to the south and west of the Town Hall were teeming with shops and boarding houses. The Market Hotel still stood on the corner of Cook Street; Wah Lee’s original shop was still the hub of a mini Chinatown. This part of Auckland was busy, thriving and not very respectable. There was talk of opium dens and brothels. Companies like Ross and Glendining had been lured to the inner city to provide decent jobs for women who otherwise might be led astray. The land for Myers Park was given to the city so local urchins, including those born to the unwed mothers sewing away in shirt factories, could have somewhere green to play.

The earliest photos of Grey Street show a dusty, leafy street of picket fences and verandas and villas. If all those houses were here now, Greys Avenue would be as expensive and picturesque as Franklin Road in Freemans Bay. But by World War I, the lower reaches of the street were squalid. Many of the buildings were boarding houses, their rickety outhouses and drooping washing lines a scruffy fringe to the Edwardian order of Myers Park.

When the name changed to Greys Avenue, the old Grey Street was doomed. Slums were cleared, Chinatown dismantled. It took a while: Wah Lee’s didn’t move to Hobson Street until the ’60s, when a high-rise block of state flats was going up further along Greys Avenue, and the area behind the Town Hall was being razed and reinvented as open space and towering civic buildings. Every single nineteenth-century building along Greys Avenue was destroyed. Today, the former Ross and Glendining factory, built at the beginning of the twentieth century, is the oldest building left on the street.

At the top of Greys Avenue, on the corner of Pitt Street, there’s the Central Fire Station, built in the 1940s. Next to it, sprawling down the park side of the street, is the Greys Avenue Synagogue, which dates from the late ’60s, and also houses a Jewish school. During one school holidays, my mother took us in there to look around; she was always trying to illuminate and educate us in new and exhausting ways. At 100 Greys Avenue sits the character-free Amora Hotel, and next to it, at number 80, is the DDB building, local home of the international ad agency.

I’ve spent a lot of time standing there, in front of the entry to the Amora’s parking garage, trying to work out where 90 Grey Street would have been located. In 1911, number 90 Grey Street was a boarding house. It was probably demolished some time after World War II. I’ve never seen a picture of it.

All I know is that in 1911, according to the electoral roll, my great-grandfather David Morris lived there. It’s his last-known address in New Zealand. After 1911 and the house on Grey Street, he disappears without a trace.

When we moved to Greys Avenue, I didn’t realise that David Morris had lived on the same street. None of us know much about David Morris at all. His main significance in our family is his last name. He married my great-grandmother Sarah Annie Wyatt on 17 February 1897 in the Auckland registry office. He was a ship’s cook, and one of the witnesses to the marriage was another seaman, a man called Savage. The other witness was the bride’s sister.

Sarah Annie was twenty-six, one of the mighty Wyatt clan of Omaha who sailed from Portsmouth in 1864 on a ship named Queen of Beauty. They owned the sawmill up at Leigh. David Joseph Morris had arrived in New Zealand more recently. The earliest trace I can find of him is 1896, when he was living on Nelson Street. His marriage certificate says he was thirty-four, born in London to another David Morris, a bricklayer, and his wife, Johanna.

In January 1898, their first son was born, my great-uncle Bob, who grew up to become a shirt-cutter and served in France in World War I as a machine-gunner. In July 1899, my granddad, Alf, was born on North Street in Newton, on the wrong side of K Road. Most of that old Newton neighbourhood was demolished when the motorway gobbled up the gully.

We have a studio photograph of David Morris and his two sons when they’re both still very small, pale-eyed and angelic. David Morris has dark hair and a jaunty moustache. He looks robust and lively to me; his eyes seem to sparkle. He’s dark in a Welsh way, and I wonder if his father was Welsh: the name is, almost certainly. He looks a bit like my brother.

It’s a happy picture, but the family wasn’t happy. By 1905, Sarah Annie and David Morris had separated. He was living in a Sailors’ Association Home in Epsom. My father said Granddad never spoke of his father; it was a subject that could not be discussed. There was no divorce, but Sarah Annie moved on. In 1911, she was living in Arch Hill with Frederick Willetts, an iron worker five years her junior, who eventually became her second husband. They had two children together, half siblings to Bob and Alf: Violet in 1911 and Len in 1913. I’ve seen Auntie Violet’s birth certificate. It reads: illegitimate.

Alf must have liked Frederick Willetts, because my father’s middle name was Frederick. My father remembered him fondly, and called him Granddad. The only story he knew about David Morris is this: when Bob and Alf were boys, a man approached them down at the wharf, saying he was their father. The boys were hustled away and told that the man who approached them was a very bad person. The men who hustled them away may or may not have been their Wyatt uncles. I don’t know. My father didn’t know. The source of the story was, apparently, Auntie Violet, who wasn’t born until my granddad was twelve and didn’t witness the incident herself. It’s all hearsay. Everyone who was alive then is long dead.

The year Auntie Violet was born, 1911, is the year David Morris was living on Grey Street. Then — nothing. The story I heard, probably from my mother who was always gossiping with Grandma and consumed a steady diet of hearsay, was that Sarah Annie finally went to the authorities, whoever they might have been, and asked for the marriage to be dissolved. Nobody had heard from or about David Morris for decades. He probably left New Zealand while working as a cook on a ship. As a member of the crew, he was much harder to trace than a passenger.

On 16 March 1929, at the age of fifty-nine, Sarah Annie was declared a widow. She and Frederick Willetts were married two years later. Auntie Violet’s birth certificate was amended with a stamp and a signature. At the age of twenty, she was rendered legitimate. This, I suspect, is the reason they got married.

Bob and Alf kept the surname Morris. Uncle Bob and Auntie Alice had no children. Granddad passed on the name to his two children, my father and my Auntie Dawn, who never married. Now my father is dead, there are just two of us left with the name: my brother and me. My brother and I don’t have children. When we’re gone, the last traces of David Morris’s name and legacy in New Zealand will be gone as well. Maybe he had another family, the way Sarah Annie did, in another place. Maybe we have hordes of dark, robust Morris cousins in some other country. Maybe he died at sea.

Maybe his name wasn’t David Morris at all. In those days, you could say anything; you could be anyone. You could say you were from London even if you weren’t. On the other side of the world, you could tell people any story you liked.

I’ve been married twice, and both times didn’t consider changing my name. It is my name, after all. But there’s not much to it, really. The name ‘Morris’ may have been a guise.

All other sides of the family bristle with thickets of ancestors. On my grandma’s, a rich and detailed whakapapa. On Granddad’s, countless Wyatts stretching back to English churchyards and harbours. My mother traced eight generations of her family in England, coal miners on one side, shoemakers on the other. But the Morris name, the one that’s on all my books — nothing.

Buildings are demolished in Auckland; names are changed. Granddad was born on North Street, now Galatos Street. David Morris lived for a while on Williamson Street, now Margot Street, in Epsom. Sarah Annie and Frederick Willetts lived on Russell Street in Arch Hill, now Cooper Street. Uncle Bob and Auntie Alice spent their entire married life living in the same house, but the street name changed from Bath Street to Wells Street to Winn Road. For many years, Aucklanders lobbied to change the name of Karangahape Road to King George Street, Fleet Street or Cheapside.

These days, the ground floor of Rendells is an Asian food hall. George Courts is an apartment block, its cage lift gone. Nobody sells gloves anymore.

My grandparents’ house on Ponsonby Road, that beautiful double-fronted kauri villa, was knocked down in the 1970s. We had dinner at the restaurant Mexico on Ponsonby Road recently, and I realised we were sitting in what was once my grandparents’ front garden. My grandparents were newlyweds when Grey Street became Greys Avenue. In the course of their marriage all but one building in the street — ours — was knocked down in an attempt to make the street modern and respectable.

The 1940s flats across Greys Avenue are framed with scaffolding at the moment, getting a fresh coat of paint. I stood outside our building the other day making a call: I was wearing a striped skirt. ‘Oi, stripey!’ one of the painters shouted at me. The flats are even more desirable these days, perhaps, now that it costs so much to live elsewhere in the inner city. The upper Greys Avenue flats, however, have aged badly since the ’50s. The block looks mouldy and unkempt, painted in sludge colours, like a sad piece of scenery in an episode of Z-Cars.

Our front windows face the street, and at night it can get noisy. Groups of drunk people stagger by on their way back up the hill to the YMCA hostel or K Road clubs, or down the hill towards Queen Street. They laugh and carouse; sometimes they argue. One Christmas Eve, an angry man, off his head, made repeat performances in the middle of the road, shouting and swearing at no one in particular.

A young couple who live in the upper Greys Avenue flats like to have ferocious rows in the street, either outside their building or up and down the road. Generally they stage their arguments around seven o’clock on weekend mornings. The woman is always the most enraged and incoherent. One evening I heard another woman across the road screaming for help, so I ran out to our tiny balcony, clutching my phone, ready to call the police. The police were already there, outside the lower Greys Avenue flats, arresting her. She was screaming because she didn’t want to get into the police car.

In 2015, not long after we moved here, a young Slovakian man named David Cerven, wanted on charges of aggravated robbery of liquor stores and a dairy, told police they could find him in Myers Park. He was standing under a tree behind our building. When he told the police he was armed — a lie — they shot him dead.

Drink, drugs, poverty, mental illness. Inner-city Auckland is the same as inner cities everywhere. Some people live in apartments that cost more than a million dollars; some people live on the street. Former politician John Banks says he was homeless as a teenager, sleeping in his Morris 8 in the Domain. Now his central Auckland apartment — on Albert Street, about ten minutes’ walk from us — is on the market for $5 million. His first business, in the early ’70s, was a coffee bar called Becky Thatcher in a Karangahape Road arcade.

We like living here, but I never walk through Myers Park at night.

Greys Avenue is a street of mostly modern buildings, just as the city planners wanted — no opium dens, no boarding houses, no Victorian hovels. The plane trees planted in 1871 give the street an elegance its new buildings lack. They were there when David Morris lived at number 90; they’re still here, more than a century later, when his great-granddaughter lives at number 68. At some point he left this street, just as one day I’m bound to leave it: if our landlords decide to sell our flat, we can’t afford to buy it.

The plane trees of Greys Avenue will remain, turning with the seasons, flourishing in the sun and the rain. They’ll outlast me and my name. Whatever happens next to this street, whatever bold new vision is devised for Auckland in its next incarnation, whatever history must be jettisoned along the way, I hope nobody ever cuts them down.

An extract from Home: New Writing, edited by Thom Conroy (Massey University Press, $39.99). Novelist and short-story writer Paula Morris is a senior lecturer in creative writing at the University of Auckland and founder of the Academy of New Zealand Literature.

This was published in the September- October 2017 issue of Metro.