Apr 3, 2025 Urban design

Along a generally featureless suburban street in Pt Chevalier stands a symbol of one of history’s most consequential feuds. It is a built expression of a cultural flashpoint, the great schism in the 11th century that inexorably altered theological and geopolitical history, splitting doctrine into East and West, and refashioning the world down to the sturdy rocks upon which it was so assuredly built.

The Church of St Milutin the King, a Serbian Orthodox church, is a small, modest building set back from the road by a clipped grassy lawn and tidy drive. Built during the First World War as a Presbyterian church, its white weatherboard construction — unadorned, moderate and practical, as is Protestant custom — belies its comparatively ornate interior. On the exterior, above a sign composed in pallid Cyrillic lettering that indicates the name of the church, an Orthodox cross, Byzantine in provenance, is pressed into the centre front of the gable facing the street. This cross, in its ornamentation, conflicts with the modern Latin version of the symbol, an ascetic sign now universally understood as that of Christ (though it was commonly registered as such only after the time of Constantine). By contrast to the Byzantine cross above me, the plain Latin cross, figured as a child might draw it, eschews any embellishment or flair, and instead speaks plainly of the direct relationship possible between man and Christ — no priestly intermediary necessary.

It’s mid-morning under a slate sky in Pt Chev and an intermediary is at hand. Michael Martin is from Texas. He speaks in a slow drawl, dragging his vowels through air thick with the sweet, heady scent of burning frankincense. “If anyone says we have to go back to the church of the Apostles,” he says, pointing his finger in the air for emphasis, “you can tell them that the church of the Apostles has a name and an address and it’s right here.”

We are standing in the narthex of the church, a gathering space between the entrance and the worship area. The room functions as a library, its walls lined by wide wooden shelves on which are arranged works of theology and liturgy, tomes on Balkan history and literature, dictionaries and language books. A table for study and assembly circumscribes the space, and the room’s walls are adorned with etchings, prints of religious figures and icons, paintings and lithographs hung salon-style in varied frames of gold and painted wood. A simple piano graced with assorted tchotchkes on its top ledge is parked next to a coat stand, carved from oak, from which a navy overcoat hangs. A large steel shrine in the corner, directly facing the entrance and visible to us through the open doorway, holds two levels of trough for parishioners to place slim yellow candles into. One storey for the living, the other for the deceased. Today, several candles are already alight and black soot smudges the wall of the shrine; they burn down into yellow stubs, floating in thick, dark pools of melted wax.

The rift between the Roman Catholic church of the West and the Orthodox churches of the East that occurred in 1054 was precipitated by internecine disagreements on doctrine and teaching. While the principles of Eastern theology had their roots in Greek philosophy, Western theology was informed by Roman law, and the differences therein led to diverging positions on several key points of doctrine. Both traditions contribute to the broad Christian church today, and both claim the term ‘apostolic’, referring to a church’s connection to Christ through his 12 apostles. The Eastern Orthodox church is led by a patriarch, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, who is primus inter pares, first among his fellow equals, while Roman Catholic convention holds to the Bishop of Rome, the Pope, maintained from the line of St Peter, to whom each new pope is considered a successor. The Roman Catholic church teaches that it is the one, true “holy, catholic and apostolic” church founded by Christ — a position, naturally, that is not shared by the Orthodox church. A mutual excommunication, initiated by Pope Leo IX during the disputes of 1054, was not revoked until 1965 after a meeting between Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I and Pope Paul VI in Jerusalem. These ancient fissures notwithstanding, the rise of the contemporary ‘megachurch’ out of evangelical Protestantism has united the two apostolic factions in shared distaste. “Over at City Impact Church,” Martin says, walking us into the nave, “I don’t know who they’re worshipping.”

☦

The story of this particular church building and its conversion into the Orthodox faith begins with a taxi driver named Mita Milovanovic, who one day in 2009 drove his cab past St Philip’s Presbyterian Church and saw a sign saying its services had moved elsewhere. He pulled over, entered, asked about the status of the church, and was told that it might soon be sold. Milovanovic then contacted the minister of St Philip’s, the Reverend Sandra Warner, who was amazed at the enquiry given that the church was not yet on the market. She suggested he and other members of his church, who at the time were holding their services in the parish hall of St Alban’s (Anglican) church in Balmoral, visit again to take a look inside. Some time later, Warner was parking her car nearby, awaiting someone from a neighbouring house, when she saw a group of gentlemen strolling towards the church. They were from the Serbian Orthodox Church, and had brought along their bishop to inspect the premises. Warner let them inside. The rest, as they say, is history.

Martin, clad in a black cassock with grapevines stitched through its fabric, is a reader in the church, a layperson ordained to read scripture, chants and lead worship (its counterpart in the Anglican church is the lector). Martin, who formerly worked as an IT analyst, migrated from Houston in 1999, prompted by increased alarm at the state of his nation. “To sum it up, 9/11 did not surprise me and Trump did not surprise me. Bush Snr decided to go to war in Iraq because he wanted to prove he wasn’t a wimp, and Clinton who followed bombed aspirin factories in Sudan to distract attention from his personal scandals… I thought, you can’t just keep doing that without blowback.” Aged 15, Martin had rejected Protestantism, “because I thought it was incoherent. If just reading the Bible is enough, why is it there are over 10,000 different Protestant sects registered with the IRS [Internal Revenue Service] in the United States, and counting? If just reading the Bible was enough, you should converge on a common understanding.”

Martin explored New Age and other ideas and finally decided that the oldest expression of Christianity was the answer. “I thought, I have to find the church,” he says, his voice animated and rising in pitch. “Not a church — the church. As in, will the one, holy, Catholic and apostolic church of our Lord God and Saviour Jesus Christ please stand up?” He went deep into researching church history and theology, a gruelling process that took a number of years, he says, and stretched back through the Reformation and various other divisions, until, reaching the 11th century, he found one side of the schism making a solid claim to exclusive truth.

The two churches can’t both be right, Martin submits. “So who’s got the better argument?

“At the end of the day,” he tells me, “it’s about who innovated. Who changed the Creed? It was the Roman Catholics. Who changed other practices? It was the Roman Catholics. So I said, ‘Okay, whoever made the change is out of the running’. The people who have kept the traditions from day one? They’re the ones.”

Martin was duly baptised at the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church in Western Springs, then wound up joining the Serbian church.

☦

The Church of St Milutin the King is open to the public every day of the week. Martin and I share a wooden pew, and he resumes his disquisition on church history and its geopolitical consequences while I survey the scene. The walls, which reach to the wooden rafters above, are decorated with painted icons, vivid works of art and tapestry, and have small, unusual windows allowing in low, milky-blue light. The eyes of the painted saints ahead gaze into the distance toward sights unseen by mortals; certain, convincing, expressionless. Fresh flowers — a bunch of upright red tulips, ghost-green orchids with coiled stems — stand in glass vases on small, squat tables covered in white embroidered fabric and rich, maroon tablecloths. A young man enters the nave, walking on the long Persian rug that leads to the icon stand, wreathed in a garland of red and white roses, where he pauses to pray.

The icon before him is King Stefan Uroš II Milutin, a Serbian king during the Middle Ages who built one monastery each year of his reign, resisted Catholic rule and had a penchant for mining, producing heavy silver coins with which to wage civil war. He is the church’s patron saint. Above the man silent in prayer hangs an enormous, glittering polyelaios, or chandelier, the centrepiece of the room. This baroque crown of metal, gold and brilliant red detailing descends from the ceiling on thick chains, its candle-flame-shaped light bulbs glowing like shining spikes of ice above the praying man’s head. Nearby, a heavy, antique oil lamp from Kosovo floats above our faces. The sound of a woman entering the narthex interrupts the silence. She is greeted by the priest of St King Milutin, the Very Reverend Presbyter Sava Amdic. Father Sava embraces her and the pair converse in Serbian, their voices hushed and echoing.

The Eastern Orthodox church has had a small presence in New Zealand since the mid-19th century, beginning with the gold rush years and the arrival of Greeks, Russians and Syrians, many fleeing the Ottoman Turks. After World War II, a wave of refugees, displaced people and migrants who were escaping various regimes, including communism, saw a rise in Eastern Orthodox Christianity in New Zealand — in particular the birth here in the 1950s of the Russian Orthodox Church, now the largest congregation of the faith in this city. Its house of worship is on Dominion Rd. Serbs, too, have a small but long history in this country, but the larger proportion of today’s Serbian New Zealanders arrived as refugees during the conflicts of the 1990s, which saw the federal state of Yugoslavia break back down into its constituent republics.

The Yugoslav Wars were brutal in their violent fissures between families and peoples. But the acrimony between Croats and Serbs, in particular, dates further back than these wars and has a religious as well as ethnic dimension, with Croatia being a predominantly Catholic country rather than Orthodox like Serbia. Here in New Zealand the memory of Croatian migration is long, with the earliest settlers arriving in the 1850s almost exclusively from Dalmatia, one of the regions of Croatia. The old-established Dalmatian Cultural Society has always been a key manifestation of Yugoslavian culture in New Zealand, and a majority of Auckland’s Serbs have links to it — despite the fact that the society, I’m told disapprovingly at St King Milutin, tends to emphasise Croatian history while diminishing that of Serbia. Even here in Aotearoa, some historical misgivings between the peoples remain.

The Orthodox church itself in Tāmaki Makaurau today is largely divided between Russian, Greek and Serbian branches, but there is also a Romanian parish in Waitākere, a Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church in Glendene, and an Antiochian presence of Lebanese Orthodox Christians in Howick. Around 70 families, numbering 300-odd people, belong to the Serbian Church of St King Milutin. Could I join, should I wish to? Absolutely, Martin answers. Typically, someone not born into the faith will marry someone Orthodox and enter the church. During and following Covid-19, both this and the Russian church experienced a rise in numbers seeking to join, Martin says, with at least a dozen catechumens, initiates into the faith, studying to enter St King Milutin. He offers several reasons for this, but principally, he suggests, “the lockdowns and madness around it shook up a lot of people. Not always in a bad way. Existential questions: what’s life all about? Is it all about the spending and the getting? They started asking pointed questions about the meaning of life.”

Joining the Eastern Orthodox church involves assiduous study of literature and course material. Catechumens are given a prayer rule, expected to complete at least one fasting period, and provided with orientation as to its purpose. In the ancient world, those entering the church would fast alongside the congregation during the 40 days of the Great Lent in advance of the most significant feast of the church year, Pascha (Easter), and be baptised on Easter Sunday. There are four essential fasts throughout the year — no animal products, but honey is allowed, and seafood without a backbone.

Considering this and the other formalities of the church, I say to Martin that Eastern Orthodox customs appear to chime with Judaism, albeit with the addition of a messiah. “That’s right,” he responds. “We took the Jewish customs and christianised them.”

Did the Roman Catholic church disregard these?

“Well,” Martin sighs. “Not all at once. Over time. Vatican II [a church council of bishops held in stages between 1962 and 1965] was a terrible disaster for them. What did they do? Oh, boy.”

Martin provides a discursive, centuries-deep extemporaneous exposition about the changes. They threw out the Latin mass, “all the beautiful masses of Mozart and Beethoven, and protestantised it with guitars. I don’t know what they had in mind. They embraced modernism at a time when modernism itself was really cratering.” Essentially, he continues, the Vatican II reforms annihilated the old church liturgies — there are even some dissenting Roman Catholics who believe the current Pope is an apostate, a view which finds sympathy with Martin.

A further problem is the rigid ecclesiology of Catholicism. “The Pope is the head of the church and can do pretty much as he wants, whereas we answer to the local church of Belgrade, where there’s a council of bishops, and the Holy Synod, who are elected periodically.” The Serbian Patriarch, first among equals, is elected for life, or on good behaviour, so to speak. “He’s not a dictator, he presides over meetings of the bishops, who have to agree on things.” In other words, no one person or group can unilaterally impose changes.

Father Sava, also wearing a black cassock embroidered with geometric patterning, returns to the nave from his appointment with a congregant. Where Martin is loquacious and animated, Father Sava, in his mid-40s, is reserved and watchful, and seems settled in his interpretation of biblical texts. He sits beneath a burgundy velvet tapestry, above which hangs a small oil lamp of engraved metal and red glass with decorative handles either side. At the request of his bishop, the presbyter moved to New Zealand 15 years ago with his young family from Belgrade, where he had studied at the theological seminary. It was not an easy adjustment.

“Serbia is a free country in its social life. My daughter is in Belgrade at the moment. Here it’s so complicated for her to organise seeing a friend, but in Serbia they sit and chat and have coffee every day. In Serbia they don’t have money, but each day they take coffee and talk.” Hospitality and generosity are central to Serbian values. Here, Father Sava continues, “you don’t know who is your neighbour. In Serbia, [the neighbourliness] is very nice. But when I see the full church, the services, that is my cross and duty to be here. In the church I feel that I’m in Serbia, in some ways.”

There is no determinative timeline for Father Sava’s stay in New Zealand. He was sent out as a disciple across the world under holy directive, and his further movements are contingent on a bishop’s decision. It’s like the military, he says wryly, “the regime change”.

Both he and Martin are here almost every day. Anyone is welcome to visit. Martin prays a section of the Psalms here most days, and regular members have access to the combination lock, arriving into a sanctuary of silence to sit, light candles, pray. On Thursdays, those who are ill come to be prayed over, and prayers are spoken, too, for the departed — who still exist, Martin says. “They’re just over on the other side, but are just as alive as we are, [though] no longer in the body.”

The parish members are a close-knit community who look after one another. No one forgets the generosity they have been shown. “I’ve had hardships and people have dug into their pockets and helped me,” Martin says. “Nobody will fall through the cracks here.” While the church is not spacious enough to have an organised kitchen, occasionally people show up there requiring help. The church provides in-kind assistance: food and clothing. Pt Chev locals are familiar with St King Milutin’s monthly bake sale out front, particularly the quality of their doughnuts.

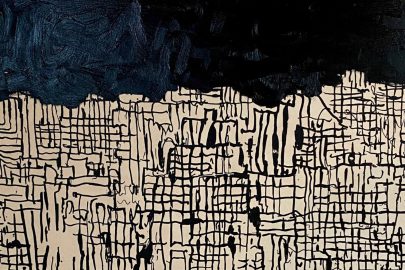

The two men walk me around the nave, and Father Sava gestures to the icons, each transported from Serbia. Above the iconostasis — a sizeable wall embellished with icons that separates the nave from the sanctuary — Christ is flanked by Saints Peter and Paul, floating on a backdrop of sapphire blue. The iconostasis was carved here and contains elements unique to these islands, including pāua shell, koru and images of native fauna engraved in its wood. The inclusion of New Zealand iconography was an edict of the former Bishop of Australia and New Zealand, who has since returned to the United States. In Roman Catholic and Anglican churches the altar sits exposed; here it is obscured behind the wall. The doors can be opened and passed through, but only by the priest or bishop; men of a lower rank must enter through side doors. But no women whatsoever.

Father Sava underscores the teachings behind this tradition. Martin assumes the role of Tevye from Fiddler on the Roof, bellowing “traditiooonnnnn” into the silence, his voice quavering in its Yiddish intonation and lodging the tune of ‘Tradition’ in my memory for days to come.

“Orthodox change nothing,” Father Sava adds.

“The faith that was delivered to the saints,” Martin agrees.

We pause before a striking painting of the Virgin Mary surrounded by a duel of light and dark in the style of El Greco. An elderly parishioner now too ill to attend services painted this, and other works that adorn the walls.

A bright-blue rug hangs horizontal on the wall, embroidered with a border of flower chains and Serbian script that frames a saint. Before it, a small to-scale model of St King Milutin’s forthcoming new church building sits atop a plinth. It is white, with black roofing and a cupola from which a delicate metal cross extends. The plan is for the new build to sit in front of the present church, which will be converted to function as a hall.

Behind the model is a photograph wrapped in plastic of the Serbian church from which the new design originates. It is beautiful, and elegant, and unlike the usual structures of this country’s built environment. When it is built, the new Church of the Holy King Milutin will no longer be an indistinct, white-weatherboard conversion, but a landmark, changing the nature of the neighbourhood. This change and evolution might remind passersby of the suburb’s former roots: its origins as a prime Māori fishing settlement; its time as a military encampment during the New Zealand Wars of the 1860s, whence the ‘Pt Chevalier’ name came; then its decades as a seaside suburb, with trams running to the shoreline in summer and a diverse, largely working-class population, including a significant elderly contingent. This varied history is at odds with the monocultural, well-heeled community of residents who live in today’s Pt Chev, who seek either its multimillion-dollar 1920s California-style bungalows to renovate or its state homes to demolish to make way for overpriced town housing. The worshippers at St King Milutin do not, in the main, reside in the same suburb as their church.

There’s no mortgage on the current Church of the Holy King Milutin — it’s all paid for. Father Sava ventures that the new church won’t cost more than three million dollars to construct. The Serbian Orthodox Mission trust that runs St King Milutin hopes that people will hire the hall for community events, and perhaps more will join the church, or at least discover what resides within its walls.

☦

As we exit the nave, we stop to visit the little narrow shop attached to the narthex. Below its glass window, the countertop greets the outside entrance, adjacent to the shrine. It’s open to anyone, cash only — prices tallied by a small calculator — and sells a range of Serbian and Eastern European goods. On the bench are jars of pickled vegetables and olives, a stack of advent calendars, postcards and booklets, prayers scribed on fancy paper to attach to one’s wall, tidy rows of beeswax candles, a rattan basket of red and blue woven bracelets. From a wooden dowel rod above the shop window hang brass bells with blue, white and red ribboning, little crosses fashioned from olive wood, and a chotki, or knotted prayer rope, comprising 50 or 100 beads to help the faithful keep track of the number of times they’ve uttered the short, repetitive Jesus Prayer asking for God’s mercy.

The shelves hold fig and plum jam, bottles of red and white wine, pâté and ajvar, roasted red pepper sauce, traditionally prepared in Serbia during autumn out of the abundant harvest of peppers and served with ćevapi, Balkan sausages. A member of the church provides raw honey to sell, and there are boxes of little cakes and Serbian sweets. Martin opens the door of a fridge decorated with magnets of assorted saints and Serbian towns and cities. Inside are piles of Serbian sausages, prosciutto, thickened goat and cow cheeses, lard, pastries filled with meat and cheese, all available for purchase. Father Sava has been busy assembling a brown paper bag of goods to offer me as a parting gift — inside is a bottle of red wine, fig strudel, honey cakes, ajvar and a jar of raw honey. He places the bag into my hands, waving away my protestations.

Outside, on the grassy berm, I contemplate the drawings and site plans of the proposed new church, which are encased behind Perspex on a wooden noticeboard with a carved cross secured to its thatched roof. Beside it is a neatly coiffed fir tree. The structure resembles a folksy hut, something you might see in a national park, though with a certain resplendence of burgundy and gold trim. A car pulls up, and a couple emerge. We greet each other; the man says they belong to the church. He is Macedonian and Croatian and has astonishingly clear eyes. His wife, tucking strands of hair upwards and securing it in a white headscarf, is Serbian.

“Father Sava is the right man for the church,” the husband declares. “A good man.” Smiling, he gestures to himself and his wife. “We are mixed. But up there,” he says — motioning to heaven, the sky washed bright above — “we are one. We are not fanatics. All religions have a book, and if they follow the book there will be peace.”