Feb 26, 2014 Urban design

Above: Champions of High St, on Vulcan Lane outside Workshop with High St running north behind them. From left: Michelle Deery of Hotel Debrett, property developer John Courtney, Workshop’s Chris Cherry and Alex Swney from Heart of the City. Photo: Simon Young.

This story first appeared in the November 2012 issue of Metro.

Here’s what happens in High St. First thing every weekday morning, service vans enter the street and fill up half the parks. They’re not delivery vehicles, they belong to tradespeople working in nearby shops and offices. They have council-issued permits to park there all day.

From mid-morning, a steady stream of shoppers drives into High St, which is one-way heading south, looking for a park. They turn left into Freyberg Place, left again into O’Connell St, which is one way north, then down Shortland St, turn once more into High, and on it goes. Many of them go round and round; a few get lucky, more don’t, and they give up and drive away.

High St is the heart of what is supposed to be Auckland’s premier shopping precinct, and it’s got problems. Parking, sure. And a whole lot more. Three high-profile fashion retailers moved out a few months ago and set up new shops in Britomart. Others, on High St and in the Chancery complex, have followed them out of the precinct and several shops remain empty. Earthquake strengthening is due for many buildings, which impacts on tenancy security and rentals, and the heritage status of some is also uncertain. The fast-growing student precinct nearby has changed the makeup of the local population.

It goes on. The recessed strip of shops and cafes under Metropolis and the council carpark at the Victoria St end is dark, dreary and under-patronised. The whole south end of the street is ugly and uninviting. The stonework in Freyberg Square (the square is the public space; Freyberg Place is the street running through it) is wearing away and needs to be replaced. O’Connell St, despite being home to several cool little boutiques and good restaurants, is bleak.

Beyond all of that, the whole city has been affected by four sweeping trends in shopping, and all of them are hurting High St.

The first is the economic slump, now in its fifth year. Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008, says Councillor Cameron Brewer, “retailers have been doing it hard”. Brewer is chair of the Planning and Urban Design Forum (a council committee) and the Business Advisory Panel (a council advisory body): it’s his job to help. There’s no obvious sign of recovery, although overall economic growth in Auckland is currently running ahead of the country as a whole.

The second is those endlessly shifting sands of fashion. What’s hot right now? Sydney is, especially with the high New Zealand dollar. So is Britomart, all big and new and sophisticated. Converted mechanics’ workshops, grungy, retro and small, are very hot — as the locations of choice for cafes, start-up fashion designers, junk shops and jewellers, in places like Kingsland and Newmarket. High St used to be hot like that, but when the hotness goes it’s very hard to get it back.

The third big trend is convenience. The council’s official “Design Champion”, Ludo Campbell-Reid, has a horror of what he calls “big-box shopping”, but he can’t stop it getting bigger and boxier. Take a drive out to Panmure or up to Albany if you’re not convinced.

Meanwhile, the big malls are reinventing themselves. St Lukes is about to burst its boundaries, switching the focus from a closed mall environment to a “high street” style. Such irony: St Lukes will do its best to create a faux High St experience that is more popular than the real one.

And the fourth trend is the internet. Online shopping accounts for only around six per cent of all retail in Auckland, but the figure is rising fast. In Christchurch, a recent survey revealed that 80 per cent of people under age 30 now do their shopping online. Unusual circumstances, of course, but that may be a habit they don’t break, and it may presage the future for the rest of us.

Tania Loveridge from the lobby group Heart of the City (HOT City, as they like to say), thinks it may peak at around 15 per cent, as we all start to remember we like real shopping, but she’s paid to be an optimist.

Actually, there’s a fifth big threat to High St. It’s the perception that it’s dead already.

Actually, there’s a fifth big threat to High St. It’s the perception that it’s dead already.

“High St seems to be dying,” Mark Thomas told a meeting of councillors last month. Thomas is the chair of the Orakei Local Board: he represents most of the inner eastern suburbs and therefore many of the shoppers that High St retailers are extremely keen to attract.

It was a throwaway remark, but all the more telling for it. If Thomas was expressing the general view of the people he knows, High St really does have a problem. Perception has a way of becoming reality.

Yet, perceptions aside, High St is not dying. Retailers like Murray Crane at Crane Brothers and Chris Dobbs at Working Style have signed new leases and recommitted to the area. Shops like Workshop, Fabric , Unity Books and Pauanesia are among the very best in the city at what they do, and Heather Gerbic at Pauanesia reports growth of eight per cent last year and tracking at seven per cent this year. Rakinos has stayed popular, day and night, while Barkers has just turned its High St store into the company flagship.

Yes, High St has problems. It also has plans

Murray Crane, happily ensconced on the Shortland St corner for the past 12 years, says no one should worry about the departure of World, Kate Sylvester and Zambesi to Britomart. “It’s part of the natural cycle. Kate Sylvester opened in High St as a single-boutique operation, but she’s got three stores now and the whole nature of her business has changed.”

When hot-shot start-ups become major local brands they rightly move on. “You applaud that,” he says, “and look to the next.”

Michelle Deery disagrees. She runs Hotel DeBrett (and did the splendid interior design work herself), and she regrets the loss. “We shouldn’t just move things around. The new places should start something new.”

But why was Britomart so appealing to those grown-up fashion brands? The answer reveals how tough things are for High St now.

Britomart is a private development owned by Cooper and Co, whose CEO is Peter Cooper, a New Zealander living in California. From the start, Cooper worked closely with local authorities: he has preserved and revitalised the heritage character of the area in return for being allowed to put up some major new buildings.

John Courtney, married to Deery and a property developer himself, says, “Peter Cooper bought that land for peanuts. Then he got exemptions on the height restrictions. He’s had a lot of allowances.”

Cooper has played a long game. His new fashion tenants enjoy a rent holiday — no one will confirm for how long — and Cooper assures them of an appropriate mix of co-tenants: high-profile, upmarket shops just like theirs, with the right kind of bars and restaurants to match. And valet parking.

Retailers talk about difficult landlords who won’t help their tenants and are not committed to the culture of the street.

In High St, conversely, retailers talk about difficult landlords who won’t help their tenants and are not committed to the culture of the street. Shops are allowed to remain empty or are taken over by some outfit with quite the wrong customer fit for their own business. Everyone points to the eyesore halfway down High St, the former Paris Texas site that is now called Snake Pit.

The council, they all say, needs to learn from Peter Cooper.

The council doesn’t want to do that. Cr Cameron Brewer says it has “a regulatory role, a planning role and a role in making sure developments are attractive. Beyond that, the council is limited in what it can do.”

Murray Crane strongly rejects this. He says the council “should incentivise landlords to get the right tenants. This kind of intervention in the commercial life of the city is no different from the council supporting art or any of the other things it puts money into, to help create a more desirable city.”

John Courtney agrees. He says the council has been happy to exercise complete control over commercial activity on North Wharf in the Wynyard Quarter, so why not elsewhere? The incentives, he believes, should be in the form of “offsets against rates, seismic regulations, etc. It has to be offset against rates. They’re spending all that money down at Wynyard Quarter, that’s our rates.”

Shale Chambers, chair of the Waitemata Local Board, which covers the CBD, accepts that council has a role, but his commitment seemed reluctantly given. “The council could do that [operate like Peter Cooper] should it choose to do so,” he told me.

Should it? “In the right areas.”

What are they? “High St. The area around the Town Hall. And Downtown, too.”

This debate has another dimension. Not so long ago, Cameron Brewer criticised what he called “shoebox shops” — little beauty salons, knick-knack shops and the like. He says he “got into a lot of trouble for that”.

Michelle Deery and Heather Gerbic are more explicit: they blame young Chinese and Korean immigrants, who they say are setting up shop with little care for commercial viability, perhaps with parental support, just to gain points for their residency applications.

“You look at those places. Some of them are empty all day,” says Deery. Both of them named High St shops they say fit this category.

All of which makes Harvey Brookes pretty angry. He’s the council’s manager of economic development. “Professionally and personally, I bridle at that,” he says. “This is a university town, a professional town. People are perfectly entitled to set up businesses here. Who are we to say no?”

Alex Swney, CEO of Heart of the City, agrees with Brookes. He says it’s a fallacy to think that a successful shopping precinct will contain only smart boutiques and restaurants. “Some of those High St retailers live in fear of the cheap shops, I know they do,” he says. “But where are they?”

He points out that there’s only one convenience store in High St, while nearby in Queen St there’s Look Sharp and a $3 And More shop. “They’re both pretty valuable. You get good kit in there.”

When the meeting of councillors that Mark Thomas addressed started talking about the kind of shops they wanted in certain parts of the CBD, Harvey Brookes, sitting next to the chair, spoke up. “I want to express reasonable caution about the role of council,” he said. Later, to me, he said, “We need to be very careful about how we go about telling a class of business they are welcome or not welcome.”

Cameron Brewer says, “We can’t kid ourselves as to the level of the impact we can have. A significant amount of the issue lies with the private sector, and with the market.” He adds that if the council should be “sitting down with landlords”, they should do it “through the business associations”.

“Council is so much bigger than all of us, and they’ve never really been supportive.”

John Courtney, along with Workshop’s Chris Cherry, another long-term retailer on High St, is on the board of Heart of the City precisely in order to engage with the decision-making process, and both have been busy promoting new plans for the precinct. But, says Courtney, “Council is so much bigger than all of us, and they’ve never really been supportive.”

The council’s failure to accept that inner-city retail survival might depend on its doing a Peter Cooper in places like High St — doing what it has done in Wynyard Quarter — was one of the two biggest frustrations I encountered researching this story.

The other? Its failure to be a responible landlord. The council owns 10 properties in and around High St, including that parking building on the Victoria St corner and the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Hall in Freyberg Square. This gives it, as Tania Loveridge from HOT City says, “an opportunity to be an exemplar landlord”.

Murray Crane says “it dumbfounds me” the council has let the carpark building and the area around it become “quite second tier”.

Sam Chapman, an urban designer involved with a new plan for the area on behalf of Heart of the City, says, “The carpark is like a pine tree. Everything underneath it is dying.”

I asked Cameron Brewer if he thought the council had a special role as a landlord in High St. “Yes,” he said, “we’ve got the odd building.” He thought some more and added, “Council can and should do all in its power to ensure a good retail mix.”

And then said, “Arguably the carpark needs to be overhauled”.

But the council has no plans to do that.

It does, however, have a plan for High St. The Retail Action Plan, soon to be ratified, declares that the CBD should remain the city’s premier shopping precinct.

That’s good to know, because it implies a substantial commitment to creating what’s not really there now.

Council planner Harvey Brookes says Auckland suffers from an “accident of history”: we’re not like most other tourist cities, where visitors go to the heart of the city, and later, if they have time, move further out. You don’t go to Windsor Castle or Greenwich on your first day in London. But in Auckland, visitors head straight for the periphery — Waiheke, the vineyards — and then, if they have time, they take a look at the inner city.

For the inner city to draw them at the start, it needs more vitality. The Sky Tower is the cornerstone of that, and the refurbished Auckland Art Gallery is important too. The waterfront and Britomart have been added to the mix — and everyone wants High St to be in there as well.

Harvey Brookes says it’s important to “start with the outcome you want first. Define what a great High St would look like.”

David Taylor, the council’s principal adviser on regional economic policy, believes, “It’s very, very important to the prosperity of the city centre, that it brings on opportunities to nurture the next generation of fashion designers.”

If he means fashion start-ups, he’s dreaming. High St rents average around $1000/sqm, according to John Courtney, which, in a typical 50sqm shop, will mean a net rental of $50,000 per year. Too high for the next generation of Worlds and Zambesis — you’re far more likely to find them in Kingsland and the back streets of Newmarket.

But High St is still attractive to fashion retailers — especially, as it happens, for men. Murray Crane has attracted competitors Nicholas Jermyn, 3 Wise Men and Barkers to his block, Working Title is around the corner in the Chancery, and there are more. These are established businesses, not the “next generation”, but along with Workshop, Untouched World, Marcs and others they give out a clear signal: High St remains on the rag-trade map.

Heather Gerbic believes the future of High St lies in having more shops like her own: local businesses with goods that are specific to the region and the country. “High St has a wairua,” she says. “A spirit. It’s here, it hasn’t been butchered, but it hasn’t been respected, either.”

She was outraged when Ludo Campbell-Reid told a meeting of retailers that what the central city needs is Coles and David Jones, and she stood up and told him so. “I said, ‘How dare you tell us we should be a satellite for an Australian city?’”

Few of the other retailers support her on that. Murray Crane and Chris Cherry are proud of their local identity but they don’t fear international competition. They’d love to have David Jones in the zone. They love the idea of Zara moving in. Shops like that would bring the really big numbers.

The council’s focus, as always in these things, is on reshaping the street. The aim is to attract more pedestrians. Harvey Brookes: “The question you ask is, ‘What would make High St more sticky?’”

The leading proposal for Freyberg Square and O’Connell St is shared space: no designated footpaths or roadways, with pedestrians and vehicles forced to co-exist.

Shared space is a European invention, already established by Campbell-Reid in Elliott St, the western end of Fort St and elsewhere. Some critics say it’s the worst of both worlds because no one knows who has right of way, but he loves to hear that. “That’s the idea! When no one is quite sure, everyone slows down. They have more respect for each other, so their behaviour is safer.”

$4.4 million has been allocated to the O’Connell St and Freyberg Square work, which is due to start next year.

“High St isn’t broken and turning O’Connell St into shared space is the thin end of the wedge.”

Chris Cherry is not happy. “Fort St and Elliott St were dogburgers,” he says. “But High St isn’t broken and turning O’Connell St into shared space is the thin end of the wedge. O’Connell St is worthy of preservation as it is. It’s a point of difference.”

John Courtney disagrees with Cherry on this. “O’Connell St is a dark carpark. You still need to drive through, but let’s move some of the cars out.” He’s looking forward to the shared space and says the four restaurants there now, including his own, Kitchen in Hotel DeBrett, are all keen to create an Imperial Lane-style experience.

In fact, there will probably be a “hybrid”, as Alex Swney calls it, with a few parks on the east side at the Shortland St end.

Freyberg Square, designed only 14 years ago by leading architect Andrew Patterson, fills to bursting every sunny lunchtime. But because they used the wrong stone it needs to be redone, and that’s created an opportunity to fix some other problems. The coffee kiosk on High St and the low wall it’s up against form a barrier to entry. The whole space is a natural amphitheatre, but it’s rarely used as such because Pumpkin Patch occupies the ground floor of the Pioneer Women’s Hall, right where there should be an open public area — perhaps even a stage.

$10.4 million has also been earmarked for High St, but work is not scheduled for another three years and planning has not yet begun. It’s worth noting that none of this money comes from general rates. CBD businesses are levied a special targeted rate which is used for CBD development.

Any chance of a pedestrian mall, with service vehicles limited to early morning? Apparently not. Retailers, even after nearly 50 years of the successful experience of Vulcan Lane, are dead against them. Chris Cherry is so vehement, he says that if the vehicles-free zone of Vulcan Lane turned the corner into High St — that’s the corner his shop is on — he’d be “out of there tomorrow”.

Cherry, like most of the other retailers I spoke to, doesn’t like shared spaces either. “Show me a city anywhere in the world where they work,” he says.

To which, DeBrett’s Michelle Deery, who does like them, responds: “Covent Garden.”

Cherry says Covent Garden is “different because of its scale — it’s got a whacking great Tube station right in the middle of it. And it’s got all those attractions.”

When I told Campbell-Reid about this, he kind of stiffened and looked away. “If you create shared spaces you can put in the attractions. Where do shared spaces work? Only everywhere.”

Including here. A just-released analysis of Fort St by the council shows pedestrian numbers up by 50 per cent, with consumer spending up by 65 per cent overall and 400 per cent in the hospitality sector.

“High St,” says Campbell-Reid, “has all the ingredients. It is certainly my favourite high street. It is perfect for shared space.”

But, he says, there’s another factor that is already in the retailers’ hands to solve. “Last year in the US, 70 per cent of retail sales occurred after 5.30pm and on Sundays.”

So are the shops just not open at the right times? Heart of the City’s Tania Loveridge sighs and says, “It’s a work in progress.”

To Chris Cherry, the biggest problem is those service vehicles clogging up the parking. And it’s an easy fix: all they need to do is give the tradespeople permits to use the council parking building.

Cherry, Murray Crane and Heather Gerbic share a strategic goal which is diametrically opposed to Ludo Campbell-Reid’s: they want to make the street more attractive for cars.

Elliott St, says Cherry, can have its shared space — it was “a dog” anyway. “High St’s not a dog. It needs protecting. People coming into High St are coming past Ponsonby and past Newmarket. They’re coming for that special old-fashioned experience.”

What he means is the ability to drive right into the street, park there and shop.

What he means is the ability to drive right into the street, park there and shop. Crane even told me High St should be a “thoroughfare”.

“High St is like Sydney’s George St,” he says. “Or Bond St in London.”

Isn’t Queen St our George St? “Not really. High St is a destination street. It’s the reason you come into town. And the people who do come in want to shop out of their cars.”

Cameron Brewer relishes this. He clearly doesn’t see eye to eye with Campbell-Reid on the role of cars in the inner city and says he would “hate to see High St become a shared space. Part of its attraction is its European flavour. It’s busy with cars. Drivers have to play Russian roulette. It’s quite gritty like that.”

Really? We want a street for Russian roulette? Brewer reflects on this. “Perhaps it should be a kind of shared space. If you took away the kerbs but still allowed people to park there, that wouldn’t be so bad.”

It’s all about “The Smith & Caughey Effect”. You keep a couple of parks out the front and people remain happy to shop there because they think they have a chance of parking outside. Shale Chambers calls it “notional parking”. John Courtney grins. He thinks it’s a good ruse.

I asked Chris Cherry if he really thinks the future of inner-city retailing relies on customers being able to park right outside the shop. He sighed and shrugged and said no. But, he added, “It’s hugely important that we do this as an evolution.”

John Courtney is disappointed it’s all taking so long. The council, he believes, missed the chance to entice Zambesi, World and Kate Sylvester to stay. “If High St had been made more people friendly — I won’t even use the term ‘shared space’ — I wonder if they would have left.”

How about this. They smarten up the entrance to the carpark building on Kitchener St, and clean it up inside too: put some serious thought into how to make a carpark not feel like a place built for crime.

They clip concrete planter boxes to the exterior, to give the building the appearance of having a green wall, and they move out all the existing tenants on the High St side — Mardells on the corner and that tired strip of cafes. They also take out some of the carparks and install a restaurant or row of bars, one floor up on High St. Underneath, they bring the shop fronts out to the street and tenant them with fashion boutiques. They take out more of the parks and invite Zara to set up shop.

Welcome to the newest proposal for High St, developed on behalf of Heart of the City by Allistar Cox Architects and the Toot Group. They’re Wellingtonians with a hospitality focus and a project list that includes the Matterhorn, the San Francisco Bathhouse and, in Auckland, Golden Dawn.

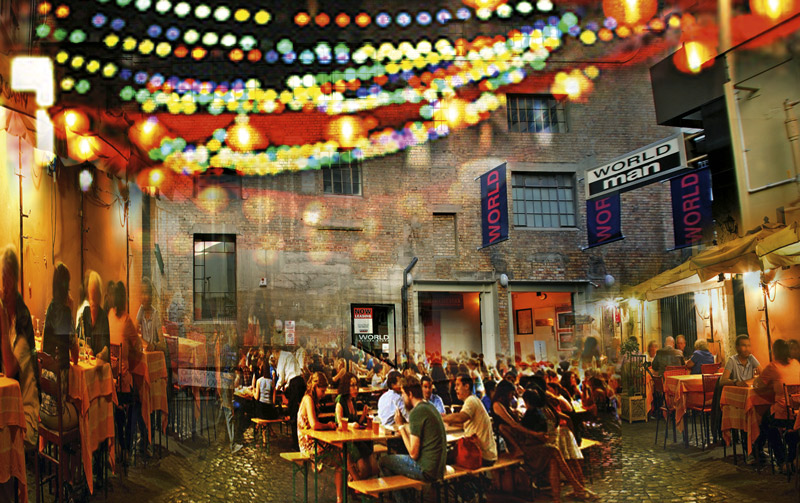

The proposal doesn’t stop with the carpark. It suggests turning Little High St, where World Man used to be, into a kind of outdoor foodhall, and introducing extensive cobbled strips of roading, planting, seating, wider footpaths and even, perhaps, a small number of carparks.

Lighting gets a makeover: Sam Chapman of the Toot Group says, “You could convert all the lights to LED, using the existing wiring. It’s cheap and easy.” They’ve proposed using colour to highlight the many beautiful buildings and illuminating the big tree on the intersection of Vulcan Lane and High St — making it a centrepiece for the whole street.

None of it has to happen exactly this way. The proposal has no official status and Chapman and Chris Cherry, who is in favour, both call it simply a conversation starter. But it’s more than that. It’s an attempt to push the conversation onto a higher level, to force the argument past petty hurdles like how many carparks there should be or where the planter boxes should go.

John Courtney says, “We need a project to unify us. It could be the Victoria St carpark.” Cherry adds that work on the carpark should be self-funding, and Shale Chambers at the Waitemata Board agrees.

“All it needs,” says Chapman, referring to High St as a whole, “is a couple of feature places. Then it becomes a journey.”

You finish work. It’s still warm so you jump on a Link bus, get off at the top of Queen St and wander downtown, hang a right and head for High St. Above you to the right, the carpark building is doing its green thing and the balcony of that posh new restaurant you’ve heard good things about is filling up fast. Underneath, the council-supported row of fashion incubator outlets beckons enticingly.

There’s a light-show installation right along the street, and it looks quite lovely in the soft evening glow. Along a bit and to the left, the tables in the Little High St plaza are full, but your friends have got there already and kept a seat for you. It’s just one drink, though, despite the appeal of watching a really cool chalk artist decorate the wall — because this is Tuesday, the market stalls are out and you’ve got some shopping to do.

Those teatowels from Pauanesia you promised your Mum, asparagus from the food market in the Chancery, a book (and the new Metro) from Unity, and, for some dude in your life, the coolest pair of stripy socks you can find in that strip of men’s outfitters they’re calling NoVu: “north of Vulcan”. Or maybe you’ll forget all that because tonight’s the night you’re going to buy yourself a sunfrock. Strictly speaking, you should be watching out for cars, but there are so many people around that nobody, surely, would dream of trying to drive through.

You get to Freyberg Square and your favourite local alt country band are in full swing. And there’s more: around the corner in O’Connell St a Samoan a capella group is singing from the windows of Wine Chambers restaurant, while back down at Unity Books they’ve got a debate on whether Christopher Hitchens was ever as funny as Caitlin Moran. You’ll have to sit down and think about this. So much choice! You make some calculations, and a quick phone call. You’re going to be on a later train home.

You’re trapped in the anti-mall. And loving it.