Mar 14, 2016 Urban design

A critique of neoliberalism — and a dairy herd — animates a New Zealand architectural exhibition.

This article was first published in the March 2016 issue of Metro. Photos by Simon Devitt.

Why the cows? Among the perplexing, perhaps teasing aspects to the New Zealand Institute of Architects’ Future Islands exhibition for the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale are 413 of them.

The digitally printed herd roves around 20 white parametric blobs: islands in nine archipelagos that will hang in space, some high, some low, in two rooms of the Palazzo Bollani. Surreal.

I encountered these bovine-infested future islands before Christmas, when exhibition creative director Charles Walker of AUT’s faculty of design and creative technologies and associate director Kathy Waghorn of the Auckland School of Architecture were about to pack them up for Venice. Ambiguous or “multi-biguous” meanings were intentional, says Walker. “They could be read as landforms, but also as clouds, or waves, or volcanic fields, or bodies in space.”

Or whimsical shelving for displaying New Zealand architecture as models placed atop, sometimes suspended below, these detached proxies of the New Zealand landscape, always so untouchable and sanctified in the Kiwi psyche.

It’s the NZIA’s second time at the Biennale, an architectural showcase running from May 28 until November 27. The first, 2014’s Last, Loneliest, Loveliest, asserted a singular Pacific narrative and a pavilion architecture derived from “poles and sticks and thatch”.

Here the story is pluralistic, still anxious about living at the end of the world, but more island-dreaming than island-hopping. It also allows for buildings that didn’t fit the narrative last time: the arrestingly arched Tuhoe Living Building, Te Uru Taumatua; the late Sir Ian Athfield’s Amritsar House.

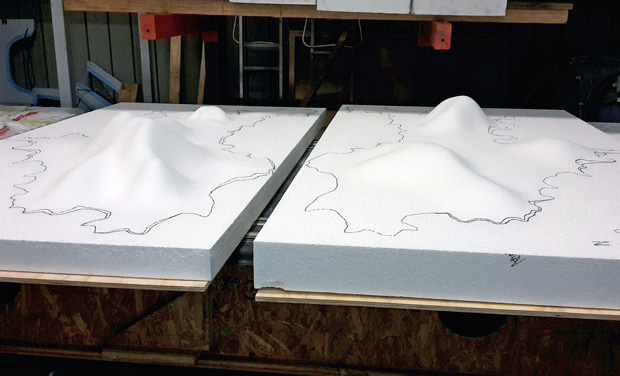

The disembodied islands are artful and high-tech, precision-made by Core Builders Composites in Warkworth, the company set up by Oracle kingpin Larry Ellison to build America’s Cup boats. Some are undulant shells of fibreglass resin-infused hemp fibre laid on moulds. Most are milled polystyrene coated in resin — iceberg–like, undulating underneath as well as topside, alluding perhaps to the upside-down Antipodes or Aotearoa’s long white cloud.

Or parametric skiting: when design parameters are computer inputs to be manipulated at will, architects don’t only dream of fantastical shapes, but model them in Rhino and more or less print them. Amid a sea of white there’s a sinuous shiny black seat made from leftover carbon fibre used in the manufacture of a Boeing 787.

There are 55 architectural models: a mix of student work and architects’ built, unbuilt and speculative designs. It’s a homage to Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, in which Marco Polo describes 55 wondrous cities to the ageing Kublai Kahn. Turns out he’s describing Venice, his home, over and over.

Walker wanted to tell the multiple stories of New Zealand architecture in a similarly compelling way.

The result is a sort of hanging garden of island metaphors, video projections and architectural clusters.

“Islands of Encounter”, for example, includes Patterson Associates’ temple to the kinetic genius of Len Lye in New Plymouth, student Holly Xie’s speculative Deception Island in Antarctica, and Cheshire Architects’ Marsden Cross building — it’s resin-infused thermoplastic and plywood roof hovering above Oihi Bay where the Reverend Samuel Marsden preached on Christmas Day 1814.

The seemingly jarring juxtapositions fit with the “Reporting from the Front” theme proposed by Biennale director Alejandro Aravena, a radical Chilean architect known for his pioneering social housing projects and as the 2016 Pritzker prizewinner.

Aravena wants the exhibition to examine the role of architects in trying to improve living conditions. “We would like to understand what design tools are needed to subvert the forces that privilege the individual gain over the collective benefit, reducing We to just Me.”

Good luck with that, especially when the role of the architect, servile to the client, struggles for social or political relevance. “Islands of Prospect and Refuge” captures some

of the dilemma: what to do in the face of governments’ embrace of financial deregu-lation and its attendant social inequality, homelessness and housing unaffordability?

Here, a quintessential ragged New Zealand coastline is populated by bespoke architect-designed baches looking out to sea. In the centre is the unbuilt Mission in the City, the winner of a visionary design competition to provide accommodation for those in need. Similarly, in the Christchurch rebuild, where the profession hasn’t exactly covered itself in glory, the “Islands of (Im)possibility” present some alternatives to the status quo.

The cows: taking a scaled-down dairy herd to Venice is, says Waghorn, to highlight other factors besides building and urban form that influence our future inhabitation — such as the country’s marriage of its economic well-being with the dairy industry, a union that gives scant regard to its impact on the country’s ecosystems.

“Maybe this is our ‘frontier’ that Aravena speaks of. We don’t have any answers,” says Waghorn. “It just seems that dairy is a powerful force in shaping the future of these islands and the cows are a small way to point to this.” The architecture of the cows.

A critique of neoliberalism animates much of this show, which includes alternative practices such as Sarosh Mulla’s Longbush Ecosanctuary welcome shelter near Gisborne, built for free with volunteer labour and sponsorship. Intriguingly, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment is a sponsor of the exhibition and commissioned a Rufus Knight-designed New Zealand Room to “promote other ‘NZ Inc’ opportunities” beside the display.

It’s a jarring juxtaposition. Or perhaps a kind of compliment. The price of getting our architectural thinking to the world.

Main image: How “Islands” will appear at the Venice Architecture Biennale