Oct 5, 2018 Travel

What happens when a 77-year-old knight of the realm experiences the extraordinary power of ayahuasca?

We are all guests of Juan, who somehow found his way here via film-making in Indonesia and Far North Queensland. He is a very interesting dude and has got me into a situation where I now wish I was somewhere else. My mouth continues to dry up because I have a feeling what’s in store for us over a weekend will transform our lives, possibly forever.

I met Juan over a bottle of Gato Negro Merlot in the North Shore Colombian restaurant El Humero. We started to talk about movie scripts and he asked me if I had swum the Amazon. I told him it was one of my bucket-list dreams — who cared about the anacondas and piranhas and the bottom-feeding stingrays. I think he spotted someone who would try anything to get through the night, but then I told him that my favourite movie of last year was the extraordinary Embrace of the Serpent, one of the most compelling films I had ever seen.

Filmed on the Amazon by the Colombian writer-director Ciro Guerra, the tale follows two explorers — using the same guide, 50 years apart — up the river, searching for possible psychedelic drugs to assist in medical research. The two major characters are based on real people. One is the German ethnologist Theodor Koch-Grünberg, who in the early part of the 20th century explored the Amazon and its tributaries, searching relentlessly for psychedelic drugs made from plants that had been used by the locals for a thousand years or more.

Watch the Embrace of the Serpent trailer:

In the movie he is dying, but not before he enlists an amazing young local guide to help him in his search. The guide is Karamakate, the last of the Cohiuano, played in the first sequence by Nilbio Torres, who is quite simply extraordinary. Karamakate nurtures the dying explorer and guides him up the rapids and through the jungle filled with snakes and every poisonous creature that threatens life and limb. The story then moves into the 1940s, when an American psychedelic researcher and botanist is covering the same territory. Now Karamakate is an old man and aware of his own impending death. He agrees to yet again take a foreigner up the river to search for the mysterious and elusive hallucinogenic plants. This 2015 movie was lauded at Sundance and Cannes and nominated for a Best Foreign Film Oscar.

I told Juan of my passion for the film and could see that I lit a spark in him about the Amazon, its mysteries and its psychedelic backstory. We decided over maybe the second or third bottle that we would become friends, that we would talk movies, the Amazon and the mysteries of life. Little did I know that I would get into a situation that would be as challenging and as terrifying as anything that the movie had to offer.

In the 1980s, I read about the brothers Dennis and Terence McKenna, who left the comforts of New York and travelled up the Amazon to find what they called ayahuasca. They introduced it to the international scene with Terence’s book True Hallucinations. The brothers were amazing travellers and they found themselves in a psychedelic paradise in which they tried everything from magic mushrooms to hallucinogenic vines and vegetables. Nothing seemed to daunt them.

I came of age in the 1960s. It was a time of music, lifestyle changes and certainly a dope culture which emanated from the universities into the cities and drifted into the suburbs. These were heady changes for New Zealand. In my world of advertising and the creative arts, dope was freely available. I was always an enemy of smoking, so I bypassed the many opportunities. But the art and the psychedelic experience did draw me with its energy and the allure of a shadow culture.

On a trip to New York in the 1980s, I became aware of the rising new mood of experimentation and social adventures in drug-land. I was also aware through the grapevine that ayahuasca had been used on the Coromandel and the West Coast at small ceremonies. Although I knew no one who had been part of it, it registered on my radar.

The Amazonian Indians made it clear that ayahuasca was medicinal. It was for healing and had the ability, unlike other drugs, to transform the patient to another level of consciousness. This ancient medicine has been the subject of many controlled-substance experiments in the United States. It has been hoped it might lead to treatments for cancer and Parkinson’s disease. Some believe it could one day change the way we think and partake in Western medicine. Right now, said Juan, over the last glass of red, I believe it is a huge global experiment waiting to happen.

Out of the darkness, our pickup truck arrives. Five other passengers from the fishing boat join me on mattresses on the back of the truck. Clearly it is going to be a bumpy ride. Introductions are made, and we work out that none of us has tried the drug before. There is an architect, a famous retired All Black, two schoolteachers and a fellow traveller whom I recognised from the naturists’ club in Ranui. We are silent. The nervousness is palpable.

We know that we are in for something that will take us out of our comfort zone. My research has told of overwhelming misery, the certainty of suffering and, in the depth of the experience, a feeling of panic and no way to escape, darkness and an absence of light. The New Yorker told of tunnels of fire and people emerging out of the depths of nightmares. How could something be so interesting and so bloody scary, I wondered. Too late now, as the farmhouse looms out of the darkness.

The accommodation and the friendship of Juan soon put our fears to rest for the evening. There are 12 individuals invited to take part. The next morning, without breakfast, we meet on the veranda and walk across the paddocks to a huge old barn. In the loft, in a massive array of cushions and straw, we meet the shaman who will conduct the ceremony.

The shaman flew in from Colombia two days ago and arrived here with a couple of schoolteachers.

He is 55, the son and grandson of shamans before him. He has with him four drums of various sizes that will be played throughout the ceremony, and a bag of objects, idols that look like they have been plucked from Aztec tombs. He wants to put us at ease, so the build-up to what we’re about to do needs careful attention. We need to breathe carefully and deeply, he tells us. We will need to refocus constantly. In the centre of the barn are 40 lit candles to focus our attention and bring us back to reality. He tells us that he has been doing these ceremonies in San Francisco and New York. He is adamant that under-qualified shamans are dangerous and can be deadly.

Ayahuasca is a combination of plants which are collected and brewed. The word itself means “the vine of the soul”. The plants have been grown for thousands of years, he says, and demand respect and correct preparation.

The main chemical in the brew is dimethyltryptamine (DMT), which has hallucinogenic properties. The shaman tells us that apprentices spend years under the guidance of elders, often spending months in the jungle learning the properties, songs and chants of the plants, which only they can hear, and asking the plant spirits to guide them in the plants’ healing properties.

The shaman claims amazing results for ayahuasca as a treatment for everything from cancer to cocaine addiction, after two or three ceremonies. So what psychological or spiritual changes are we seeking, he asks.

As he gently starts to play the drums, moving from one to another, we are asked to focus on the candles and prepare ourselves spiritually and emotionally for what is to come. Our host hands out small buckets for purging, as it is clear vomiting is part of the ceremony, and we are also encouraged to use the long drop — two or three times if necessary. The spirit of the plant takes no prisoners and anything can happen to the body under its spell. This is no laughing matter and the jokes are few and far between.

The shaman starts to chant and it’s a mixture of religious and ancient sounds; he seems to be able to bring into play a range of bells and flutes, but these come as if from nowhere. He also produces two feathered fans that, when shaken, give the unmistakable sounds of birds flying to the ceiling. I have a feeling that the room is darkening. The shaman pours a dark, thick, treacle-like substance into a small beaker. We will all drink from the same vessel. There is a feeling of anticipation mixed with fear and excitement.

The shaman’s magic works its spell on all of us. We lie back against the barn walls and each is called up to walk around the candles three times before kneeling — communion-like — to take the liquid. It tastes like mud and bitter liquorice. It spends no time on the tongue or in the throat but goes straight to your stomach. You know you have ingested something powerful.

I return to lie back against the wall and have a great feeling of contentment and wellbeing — and also that nothing is going to happen. I have escaped the terrors and it is with a sense of relief, and maybe even a smirk, that I decide this is simply not for me.

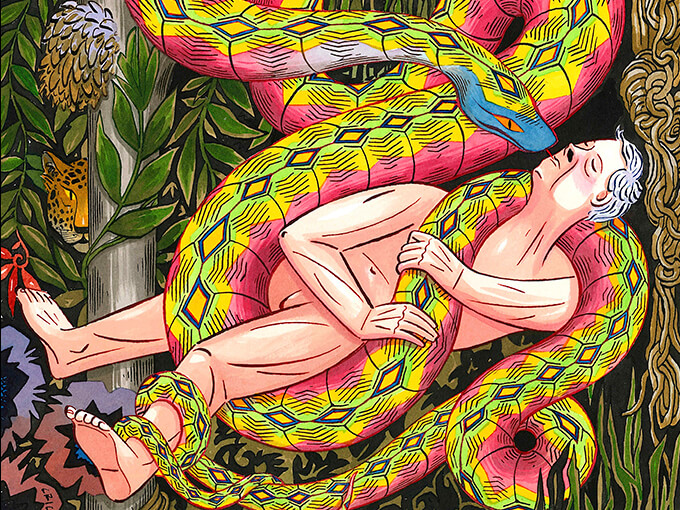

Then an extraordinary shudder takes over my body. Gently at first, like a small rolling earthquake, it moves up from my gut to my shoulders and into my neck. It’s difficult to describe the sensation that connects you with the plant. I feel my fingers tighten on the cushions as, before my eyes, the largest serpent rises across my vision.

I have a memory of a dare I undertook in a New York apartment many years ago to hold a massive python. I remember thinking at the time, because I had seen many Tarzan movies, that if I held the head in one hand and tail in the other it could not crush me. That experience was unbelievably pleasant, as its muscles moved effortlessly in its huge body and I was embraced by this creature.

This time, I am being drawn into a psychedelic-coloured experience of a massive python more of anaconda proportions. It is difficult to separate my being, my size and my place as I am pulled relentlessly into the serpent’s embrace. It is not pleasant. It is overwhelming, and I feel that I have no escape.

The serpent has come, as I thought it would, and has taken me and owned me. There is no escape.

This experience in this first part of the ceremony is beyond anything that I have known in my life. Around me the other recipients start to vomit into their buckets and I find myself uninterested in their suffering or problems. I can focus only on what is happening in my own brain. I’m aware my legs will not work. I couldn’t head for the door or a window even if I wanted to.

I move in and out of this experience, which the shaman told us would take two to three hours. This is the time of the serpent, this is when the ceremony moves the participants to the next level. Light seems to vanish and I find myself aware of another mouth, somewhere near my chest, that I am breathing through and touching. The shaman gives me a drum and I play it beautifully. I am a drummer, but I have a new feeling as my arms enter the drum and play it from the inside and become the sound. Soon, as he told us, I am aware of a flash of light — more of lightning, although the sky outside is clear.

I look around the room and my fellow travellers are in a state of unconscious and unmoving ecstasy. I wonder where they are, what they are into. What spirits are in them and where are they travelling?

Around me the group breaks into those who are enjoying it and those in total anguish. Some cry out in perceived pain, groaning and vomiting. Others smile, as I do, and lie back enjoying this total eclipse of life. I can view it from day one to now, and as the second phase breaks in, I can view the future. This time is for the lifting of the sacred chants and songs. Our shaman moves around each of us, whispering and blowing onto our heads a sacred juice like a spray of holy water. We lift our clothing so he can blow it on to our backs and chests. It’s cool and refreshing, with an anaesthetic quality.

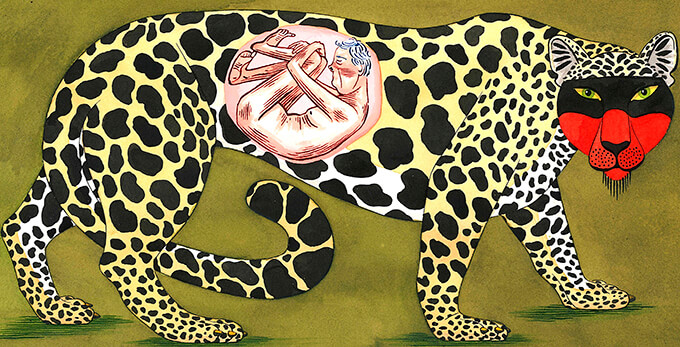

The shaman has the ability to become a creature of the Amazonian jungle in his own right. He comes close to your ear and emits the sound of a jaguar, then a tapir, and the gentle hissing of a serpent. He becomes every creature that your mind delivers, and always he is releasing in front of you a flock of birds that soar upwards from the feathered fans he throws skyward.

The dreams intensify in bright neon glows; nothing is dull, and everything is in sharp, brilliant, pulsing psychedelic colour. You glimpse it in Embrace of the Serpent as the American explorer, exhausted and close to death, is given a magical potion by his guide. The screen moves from black and white to colour and an extraordinary psychedelic experience pulls him back to life.

This is when I fully realise the total engulfing experience that my mind and body, spirit and soul are sinking into. I am desperate to escape but have nowhere to escape to. I have a lot of energy and my bucket is empty. Only three of us haven’t vomited. The shaman has taken his own medicine and retches effortlessly into his own bucket. There seems to be no smell. At this point, I dare to look at a watch I have hidden in the cushions and realise I have been in this state for seven hours. It’s late afternoon.

The documentary The Last Shaman is worth viewing. A suicidal young American college graduate believes he will soon end his life if he doesn’t get help. His parents and medical practitioners seem unable to help, so his father pays for a trip to the Amazon, where he tries two shamans. One experience is absolutely bizarre. Panicking, he moves into the jungle seeking help, and in the second encounter he has an amazing experience. After a 40-day fast and being buried underground, then dug up to be given a second chance at life, he is transformed.

My experience echoes this documentary. As the hallucinogenic period begins to ease, your life rolls back. You emerge refreshed. Your doubts, fears and paranoia gradually lift. You feel as if you have died and been reborn, given a second chance and a feeling of total satisfaction, without guilt or any of the downsides of substances, medical or psychedelic.

You need to stand, and it’s difficult. You hold the walls of the barn and feel like you are taking the first steps of a newborn. You do have an overwhelming sense of harmony and, as Freud described once, an oceanic feeling. You have reached a stage of utter tranquillity, and even of connection with the cosmos, the universe and eternity. You have cleaned up your act and now it’s time for drumming, passing the drum around the circle.

The candles have burnt down almost to waxy stubs. I remember to breathe as instructed — and I think that has got me through to the space I am in.

The barn is very quiet; we hardly want to speak. But then we start asking those next to us how it was for them. It seems so deeply personal, like a dream you don’t want to share.

When we break the silence, many admit they were terrified by the arrival of the serpent. It is the common thread to many in the room. The experience had opened, like a grand overture to the trip, with the arrival of those massive psychedelic coils.

You now need sustenance, maybe some bread and a slice of cheese, I’m thinking. I stand and walk out of the barn and up the grassy slope to the house. Someone has lit a huge fire of logs and fallen trees in the paddock. The smoke billows skyward and I’m very conscious that the day is rapidly coming to an end. I feel totally and absolutely alive. I’m pleased I have done it and survived, and I shake myself and beam a rather satisfied smile, of someone who has created a new space for himself in a challenging life. All my possibilities seem endless and the rest of this journey could be better than I ever imagined.

As I reach the edge of the fire and feel its heat, one of the guys from the group looks over to me and asks how I feel. Then that question: would I do it again? No.