Feb 25, 2021 Travel

Lorde’s childhood obsession with Antarctica was reawakened by a fear that climate change could reduce it to slush. She discovers a place that feels eternal but is perilously vulnerable. Visiting it is thrilling, but should she even be there?

Photography by Ella Yelich-O’Connor & Harry Were

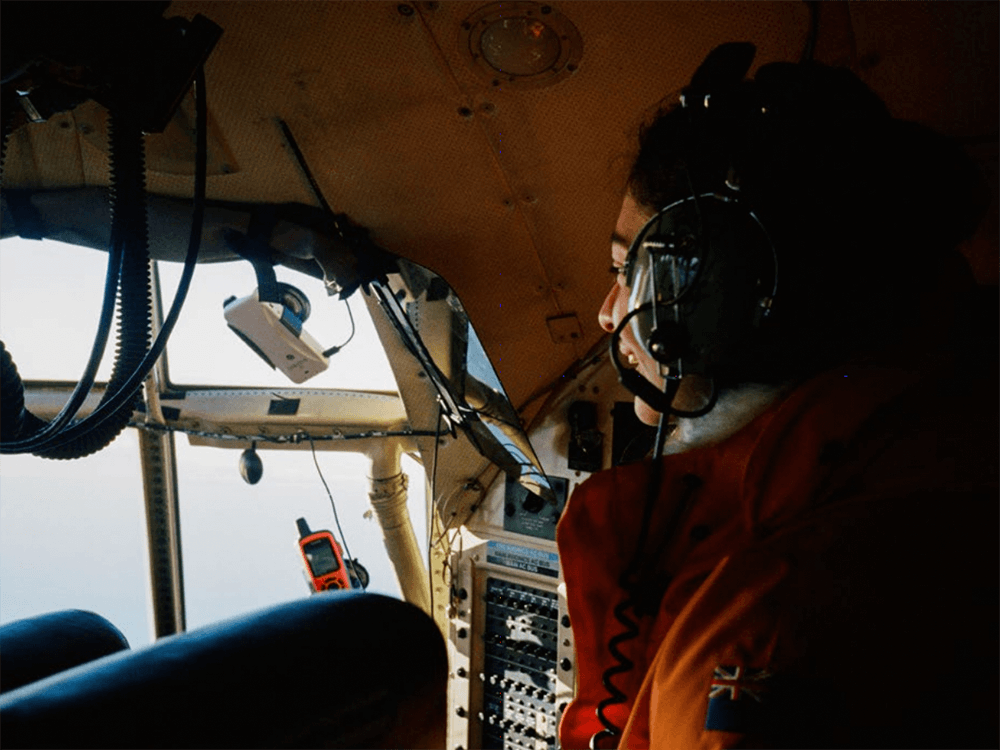

It is midnight in Antarctica, and the sky is the foamy yellow-blue of a summer afternoon. I’m in the front seat of a helicopter, its doors and windows flung open to the icy air, four pairs of eyes scanning the channel below for killer whales.

Low chatter comes through my headphones — “Yep, Mac Centre, this is India Bravo Romeo…” “…the father? Two o’clock.” The air pricks with urgency — the season has been a disappointment and is drawing to a close. Suddenly, a pair of orcas come into focus, mother and calf nosing their way down the channel. The helicopter curves in pursuit, air roaring in the blades, a steel kite hovering 50 feet from the ice.

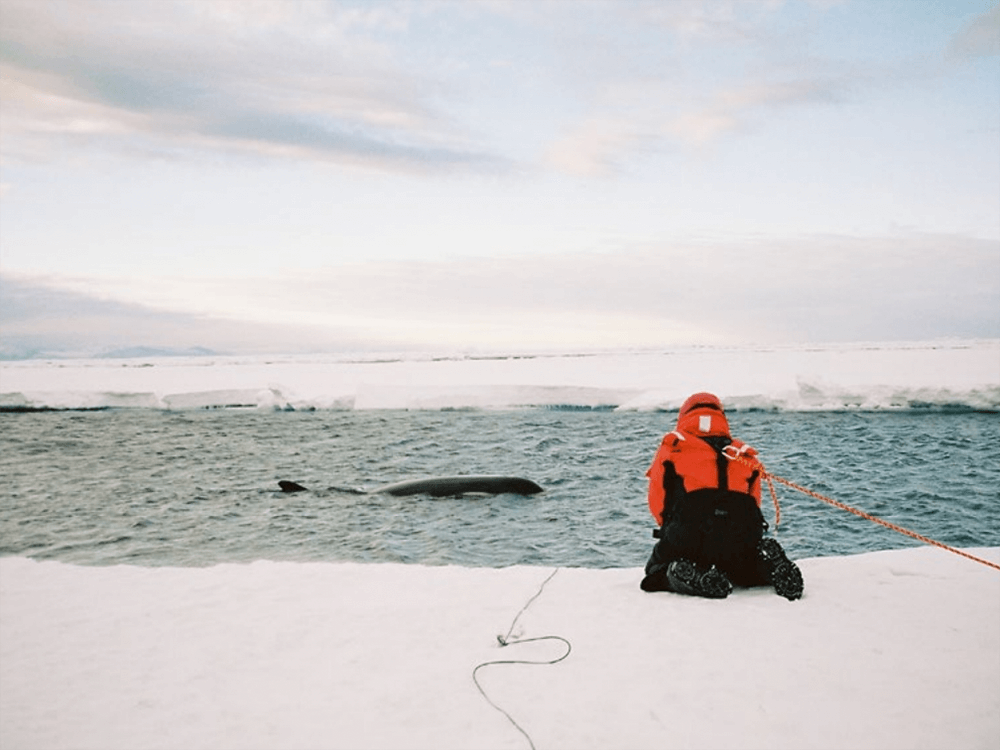

Behind me, a German woman named Regina cocks her rifle. I take a sharp breath in. The helicopter drops closer to the sheet ice, until we’re a foot above ground. One of Regina’s team members jumps out brandishing a drill with a three-foot bit to test the ground, plunging it into the ice, all the way up to the hilt. Happy with its density, he gives a thumbs up and our aircraft touches down.

All at once, the orcas surround us, huge glossy black barrels churning the water. Regina walks toward the whales, until she’s right on the edge of the channel, perilously close to the freezing water. She waves her arms, cooing and laughing in delight. And they talk back, their clucking and gurgling like an alien birdsong, breaching closer and closer. Carefully, she picks up the rifle, looks through the scope at the dark waters, takes aim and fires. Her dart hits tissue. The scientist is happy.

This is Antarctica — the highest, driest, coldest and brightest of the seven continents, as big as the US and Mexico combined. A land without a single citizen or cop or tree. A ruthless frozen desert, now supplying purest medical-grade Instagram content to wealthy adventure tourists and Victoria’s Secret models.

My obsession with the place runs deep, galvanised by a visit to an aquarium as a child, where I had won a competition to hold my arm in a bucket of ice water longer than any of my classmates. On that trip, I learnt of the breathless, romantic race to the South Pole in 1911-12 by Robert Scott and Roald Amundsen. Drawn to Scott — at first probably only because his middle name was Falcon — I found myself fascinated by the slow deterioration of his party. The story is grimly illuminated in several diaries — the frostbite, the deaths of his men, and then, upon arrival at the pole, the discovery of his rival’s flag, planted 34 days before. The high drama of Antarctica compelled me. I knew someday I’d have to see it for myself.

Throughout 2018, the heated global discourse around climate change was coming to a furious, bubbling head. The Trump administration had the previous year announced its intention to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. In August, Swedish 15-year-old Greta Thunberg painted her simple sign and, taking a seat outside her nation’s parliament, mobilised a generation of passionate youths desperate for climate-protecting law reform. That summer, while our skin burned, my friends and I sat on beaches reading The Uninhabitable Earth. I envisioned Antarctica slowly turning to slush, flooding the Southern Ocean. The urgency I had once felt about making the trip south returned. I made phone call after phone call, got several dozen booster shots, and then it was happening — this dreamy musician was hitching a ride to the end of the world.

By January, Christchurch is neck-deep in its hottest summer on record. Inside the Antarctic depot, I pull on my fifth layer of cold-weather gear, and feel the beads of sweat rolling into my belly button.

Everyone I meet tells me that Woody’s the boss. A tall, solid man with a crooked-teeth smile and crinkling brown eyes, Paul Woodgate is Antarctica New Zealand’s logistics manager, in charge of any person or thing that travels in or out of Scott Base. He’s been doing this since 1981, and is even the proud recipient of his very own Arctic crest, just west of the Churchill Mountains. He doesn’t fancy my chances of a morning flight. I poke my head out of the office door to listen.

“If I was a betting man, I’d say you won’t be leaving until tomorrow night, maybe the day after,” he says, scratching his cheek. Conditions have to be perfect for a 40-tonne aircraft to land on a compacted ice runway.

I duck back around the door and begin the gruelling process of taking off all the layers, several of which are now glued to my body with sweat. Emerging with my mountain of kit, I try not to look flustered. “This is all part of it,” Woody says, exiting his office and seeing my face. “Everything takes a little bit longer when you’re going south.”

I keep hearing this turn of phrase to describe the Antarctic journey — When you go south; When I went south. The colloquial meaning of the phrase isn’t lost on me — “to decline, deteriorate or fail”, according to the Collins English Dictionary.

Woody is right: our departure is pushed again and again before we leave. Antarctica New Zealand classifies the few artists and public figures it hosts a year as IVs, or invited visitors, a ranking that gives my departure a high priority. A woman I speak to at the gate who is joining the cleaning crew at another base has been deferred for almost two weeks, showing up to the airport over and over in her snow boots and jacket.

The plane you go south in isn’t a normal aircraft. There are no TVs, no little tables for your meal and drink. It’s a great dark shell, all sacking and stencilled DANGER signs and exposed wire. A toilet is mostly hidden behind a khaki curtain. We take our seats along windowless walls, facing our bags, which are heaped and strapped down in the centre. Regulations mandate that we’re in full emergency gear for the flight, our giant jackets and boots making us look like new schoolchildren with their too-big backpacks. The hum of nervousness in the air swells as the plane groans into life. We listen to the Air Force airman as he rattles off safety instructions at speed, his voice rising as the plane starts to move. I shut my eyes and leave my family behind, putting my life in this stranger’s hands, his voice growing higher and faster as the engines start to roar. We are going south.

Emerging from the darkness of the plane into the virgin landscape of Antarctica is an experience my brain doesn’t have language for. It’s 2am, perfectly clear, just wide blue sky and golden light. All of it feels incorrect, psychedelic, like one of those dreams where the laws of physics are subtly ignored. Around me, people are staring and laughing with excitement and twisting their heads to take it all in. It’s like returning to cellular reception after some time away, all that new information falling through the air around your head.

There are 31 countries with active bases in Antarctica, I’m told in the tank-like vehicle zooming towards our camp. The two closest geographically are New Zealand’s Scott Base and the United States’ McMurdo Station, just two miles apart. Scott Base is the scrappy younger sibling, with only a dozen residents in winter and 80 in high summer. The base comprises a huddle of simple prefabricated buildings, connected in long rows like an outsize rabbit warren. McMurdo is the rumbling patriarch, with close to a thousand beds filled when I visit. It’s part college-dorm block, part decrepit Siberian oil town — a scatter of barracks and laboratories and endless piles of rusting machinery and wooden pallets clustered near the grey waters of McMurdo Sound. There’s even a small white-painted church called the Chapel of the Snows.

Our days in the field are thrilling and exhausting. My eyes never adjust to the flat whiteness, or the gnarly mirage duplicating the mountains over and over on the horizon. There’s often an eerie lack of sound — no whisper of breeze, nothing for it to blow through. It’s so unendingly cold that my animal brain starts to think of global warming as a sort of children’s nonsense. We climb small mountains, explore crevasses, ride in helicopters to the farthest reaches of New Zealand’s Antarctic jurisdiction. At the end of each day, we eat ourselves numb and fall into bed, the sun shining ceaselessly above us as we sleep.

To go south, it turns out, is to temporarily loosen one’s grip on the throb of popular culture — hip-hop feuds, Trumpisms, the Marvel Cinematic Universe — and enter a surreal alternate timeline, not past or future, but something more akin to long-haul space travel. There’s no Wi-Fi at Scott Base. You can’t download a song or watch Netflix. You have to actually talk to one other, gathering in the simple prefabricated rooms, cellphones nowhere to be seen. These are great scientific minds , and while they spend their strenuous workdays receiving and interpreting intricate biological code, their leisure time is not unlike the after-dark hours at a school camp — comedic, vaguely politically incorrect, yet strictly adhering to all safety guidelines. For the Scott Base crew, this means a half-marathon on the hottest day of the year, in underwear. It means getting loaded on tax-free beers in the base’s bar, the Tatty Flag, and then having drunk toast-eating sessions in the dining hall. It means a seriously bizarre amount of dressing up, for almost any occasion. One afternoon, in my search for a private landline, I accidentally stumble upon the costume room — a half-dozen racks heaving with animal suits, rainbow wigs and several pairs of fake breasts.

The close quarters and lack of internet encourage congregation over meals. The food is dense and starch-heavy, and my delicate Herne Bay constitution is given pause by the multiple forms of cooked dough. I’m constantly full, yet can’t stop. I start to feel like there’s a deranged glint in my eye at all times.

Fresh fruit and vegetables are an almost impossible rarity and the chefs make do with all manner of frozen and tinned goods. One day, a solemn, sweet Navy chef named Quentin is taking stock of the pantry when I walk into the dining hall. “People are gonna get pretty sick of sultanas,” he announces glumly. The kitchen crew have just discovered a massive surplus — eighteen kilograms, to be precise. In the coming days, I notice them everywhere — adrift in meat stews, tangled through carrot salads, studding buns and puddings. I start to brainstorm my first meal back in Christchurch. I literally dream about cucumber.

Long stretches in the dining hall introduce me to a multitude of scientists, some of whom have been making the trip south for 30 or 40 years. My first impatient question for each one is if there’s any tangible climate change they’ve witnessed on the continent, some evidence of its degradation. A senior Adélie penguin researcher points to a cliff of ice not far from the colony he’s observing. “Well, that melts faster and farther every year, for one thing,” he says. But many are surprisingly reluctant to go on record about their experience of Antarctic warming, choosing instead to let the statistics they gather speak for themselves.

Antarctica plays something of a confusing role in the planet’s warming trajectory. In the Arctic, its northern counterpart, temperatures are rising faster than almost anywhere on Earth. But while the western Antarctic Peninsula reports similarly rapid levels of warming, other large swatches of the continent have seen no change, or are even trending cooler. Ian Hawes, a leading Antarctic ecologist from the University of Waikato who has been travelling south since 1979, tells me much of the disparity has to do with its unique geography. “It’s a piece of land on a pole with relatively few land masses around it, in its own isolated patch of air,” he says. The westerly winds further isolate the continent from climate systems on other parts of the globe.

The Arctic is surrounded by other land masses, and many rivers flow to its sea, making it much more vulnerable to rapid melt. In my chats with Hawes, I sense his pessimism about humans reacting fast enough to prevent the current forecast temperature rise. I’m familiar with the feeling he describes, of looking around at people and politicians, and having less and less confidence that mankind will respond with the appropriate urgency. I ask him what he thinks the continent will be dealing with in the next wave of major warming. Hawes pauses, and takes a breath in. He chooses his words carefully, as I’ve come to expect of the scientists when they’re describing potential catastrophe.

“My expectation,” he says, “is that in a couple of hundred years’ time, Antarctica will have much less ice, particularly western Antarctica, as the sea levels will have risen by several metres. Organisms will be distributed in places they never have before.” He coughs. “We’ll still have penguins, of course. But they’ll be different penguins, in different places.” It’s difficult to frame what he’s describing as a doomsday, though I know it is. It’s a lot easier for me to see the ever-worsening California wildfires as an emergency. That’s the thing about Antarctica — this harsh environment feels eternal, but is dangerously vulnerable; it is vitally important to the future of civilisation, yet essentially uninhabitable, and for most people, impenetrable.

“Antarctica is kind of the last bastion,” Hawes says, “an icy castle at the bottom of the Earth that’s just holding out, fighting against the Anthropocene.”

Being in Antarctica isn’t always fun, exactly. It’s thrilling, and spiritually intense, but as the days go on, I find it hard to shake the thought that I really shouldn’t be here. It’s so clearly not an environment fit for humans to inhabit. The sheer effort it takes me to stay alive for five days while the continent does its best to expel me is exhausting.

New Zealand doesn’t encourage or facilitate tourism, but visitor numbers across the continent have risen steadily in recent years, due in large part to a phenomenon known as last-chance tourism. You know the drill: you read an article about a great natural wonder beginning its inevitable march into ruin, and immediately you’re pulling up flights, quenching the primal need to see it before it’s too late. Ironically, this wave of tourism has generated increased carbon emissions, due to long-haul air travel and damage to overextended infrastructure. In 2011, the International Marine Organization introduced new restrictions around the kinds of fuel that can be burnt in Antarctic waters, and cruise ships visiting the area are purportedly much greener. Staring at another spotlessly clean sheet of ice one morning, I wonder how many Antarctic tourists leave the continent feeling as I do, indescribably fortunate and quietly guilty all at once.

One day, I belay down a crevasse, deep under a glacier. Waiting for the others in my party to go first, I feel hot and fussy, tugging at the tight harness around my thighs. Nerves shimmer in my stomach. Gripping the rope tightly, I step off the glacier into nothing, the bright sky disappearing above me until I’m engulfed by the blue dark.

The crevasse is a hundred feet deep and barely three feet wide, and the light is low. It’s like standing inside a petrified wave, the uppermost crest frozen in lurid turquoise facets. Thousands of years of compacted ice has melted and frozen around this tomblike space, and the air feels thick and fossilised, our voices a disturbance. The ice clinks underfoot as we walk in deeper, an angry sound like metal scraping metal. With each step, I’m scared I’m breaking something, altering the crevasse in an irreversible way. The space between the smooth walls starts getting smaller until it’s barely wide enough for my shoulders to fit through. Placing one foot in front of the other, I inch forward, my jacket shaving ice from the walls in a fine mist. My eyelashes have frozen. I shouldn’t be here, I think. I’m intruding. Do not linger, the blue walls seem to groan.

It’s a strange sensation, staring open-mouthed at nature in its rawest form and being met with pure hostility in return. There is nothing sentimental or gentle or nurturing in this natural environment, none of the womb-like qualities of a warm summer sea or humid forest. It can’t be tamed, or domesticated, or possessed. Antarctica is not your mother. It’s not going to cushion your fall.

For one of the most startling hours I spend in Antarctica, my eyes are glued to a screen.

Ben King is a wild-haired diver and mechanical engineer. He co-founded Boxfish Research, makers of a remotely controlled underwater camera about the size of a carry-on suitcase. I track him down late in the afternoon of our third day, just as he’s waking up. “I’ve been doing night shifts, getting some cool footage with Regina and the whale guys,” he yawns as we pull on our boots. King and another crew member have cut a hole in the sea ice out the front of the base.

I sit beside it, holding a laptop as they boot up the camera, thinking of Scott’s journals — “As one looks across the barren stretches of the pack, it is sometimes difficult to realise what teeming life exists immediately beneath its surface.” How could the ocean contain anything except more blinding white?

Almost immediately, the computer screen goes black, then blue, as the Boxfish plummets 50 feet downwards through the frigid water. We huddle close, blanket over our heads to block the glare. And then a week of blinding white gives way to a pastel dream — luxuriant foamy oranges, blushes of pink, elegant milky corals draped in the fine gossamer of ocean weed. Creatures are everywhere, halfway familiar, as if drawn by kindergarteners; bodies opalescent and translucent, hearts and parts glowing like raver beads. Strange fronded worms sway like tiny palm trees in the current, brushing up against feathered starfish and slender orange sea spiders.

Through the camera’s lens, we wander the carnival of the ocean floor for almost an hour. There are plush suburbs and poor ones, wastelands carpeted with dead sponges and weeds and broken starfish. A few times, I spot evidence of human life, like footprints on the moon — a red silk perimeter flag, a piece of rusted steel. These fragments could be 100 years old, I realise. They could be Scott’s.

The hour is up. Ben starts navigating the Boxfish back towards our hole in the ice, the ocean floor blurring below. A metre beneath the surface, I see the underside of the sea ice for the first time, mottled and translucent, light shafting down at the camera in brilliant aquamarine. Hawes described this to me as the blue cathedral, and I feel something truly holy, suspended beneath the continent.

At that moment, a breathtaking rainbow fish swims into frame. Angels sing. Here is the cathedral’s icon, its born star. We watch it swim as if beneath a spotlight. Ben navigates closer, trying to see it in perfect focus. Its flesh undulates, hypnotic.

There’s a flash of bright debris, a dusty cloud. “Whoops,” Ben says. We’ve flown too close, and one of the fish’s long fins has been shredded by our propellor. We exchange a grimace as it swims away. Leave no trace, huh?

Lying in my bunk on our last night in Antarctica, sleep won’t come. I am somewhere I’ll never be again, and tomorrow, the door to this alternate realm will close to me.

Throughout the week, I’ve been reminded of an obvious fact, over and over — that witnessing the natural world is the most important reason to be alive, that its wellbeing matters above all else. Being in Antarctica has clarified how deeply vulnerable, how in need of protection, it is. But it took coming here for that knowledge to galvanise — and in coming here, I have also been a small part of its deterioration. How could people possibly be expected to protect a place like Antarctica without ever seeing it for themselves?

Saving the planet often feels like the most oblique of undertakings; we attempt to pay off our predecessors’ environmental debts in the hazy hope that our descendants will thrive. We are required to see without really seeing, to protect without possessing. This disconnect can sometimes feel like viewing an impossibly bright light from thousands of miles away — we know that it’s blinding up close, but that quality dissipates so many times removed from the source. Protecting things that are not for us — things we cannot enjoy or consume and nevertheless may lose — is a lot to ask of a species hungry for faster and brighter gratification, less and less distance. It requires both a kind of primal foresight and the emotional bandwidth to tune into it, the privilege of taking space from the stress and pain and clutter of modern life to focus on a searing southern star. It’s the most that has ever or will ever be asked of us, and we have to believe that people will respond in kind in order to keep on living.

As the week comes to an end, I say my goodbyes, and whisper a private prayer of thanks to the continent. We board the plane on its icy runway and return to Christchurch.

Outside the airport, it’s dark and humid, leaves fluttering in a hot breeze. Everything has a smell: the dank rot of vegetation, the warmed asphalt. In the taxi, I roll down the window, watch the street lights mingling with the trees. I’m happy and tired, but I’ve lost something I feel I can never get back — a kind of reverence, a focus reserved for the Chapel of the Snows.

I pass a dish of apples on a sideboard as I wheel my bags through the hotel lobby. I’m reminded of the decadence of fresh fruit, a king’s basket.

Alone in my room, I find my phone at the bottom of my bag and switch it on for the first time since going south. My notifications fall like rain.