May 10, 2017 Transport

Auckland is on the verge of a major leap towards being one of the world’s great small cities. The catalyst: a renewed commitment to decent public transport.

Yes, public transport. Arguably two of the least glamorous words in the English language; rendered even more dreary in combination (no wonder the Americans use the more concise and evocative “transit”). And for a long time the experience of it in Auckland has matched this: it has been so hopelessly slow and déclassé, as if the city and the nation’s transport institutions had no faith in the product, and for decades, indeed, they didn’t.

So for many Aucklanders, especially those living here in the second half of the last century, useful and attractive transit was only something experienced overseas: London’s Tube, the Paris Metro, Melbourne’s trams. We have typically only considered it fit for other places: bigger, older, more vibrant cities, not Auckland. In Auckland, we love our cars, we’re different. So what’s changed, and why am I so sure? I’ll look at the evidence in a moment, but first, here’s an even bolder claim.

We are really only at the beginning of this transformation; Auckland is on the threshold of another one of its great morphings. And done well, this profound change is perhaps the key to turning Auckland into one of the world’s great small cities.

Only by adding a high-quality transit network to complement the all-but-finished motorway system — and by relieving the chokehold of congestion it creates for itself — can we unlock the value in our important urban economy through the efficient movement of its key resource: people.

But the kinds of transport systems a city chooses to build determine so much beyond simply getting people and things around. They help to determine the health of the population, how active people are, how many die or are maimed by our biggest killer (road vehicles), the quality of the air and water, how much space there is on streets for trees, just how accessible and enjoyable parks and our urban beaches are — indeed, how much space there is for people at all. Above all, a city’s transport-system choices determine quality of place and life.

Creating great, more attractive, effective and complete transit and active (walking and cycling) networks is the key to improving all these areas.

Without getting this part of the city’s kit right, and quickly, it is likely that Auckland will drift into poorer economic and social performance, choked by congestion, marred by inequitable access to work or study. The city will just continue to spread in a dreary, traffic-blighted way, its new places entirely without heart or distinction.

We know good-quality transit works in Auckland. We have learnt that from the already successful starts made this century: Britomart, the Northern Busway, rail electrification.

The success of the Britomart redevelopment rests on the tens of thousands of people arriving below it every day, each leaving their space-hungry car at home, enabling that vibrant public space at street level to flood with people, making it available for people and their social and commercial transactions, with the remaining road space freer for delivery and other necessary vehicle tasks.

This kind of uplift can happen all over the city, in all its centres, if we plan and invest in it. But only if we deliver the necessary high-quality, car-free access network.

These flow-on effects of transport investments are not vague nice-to-haves, but critically important to the performance and well-being of the whole city. They are in fact the entire point of investing in transport: transport systems are not ends in themselves but means to other human ends, and like all other urban infrastructure have been critical in the success or otherwise of cities throughout history.

Rapid urbanisation driven by the industrial revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries led to terrifying outbreaks of epidemics caused by insanitary water supplies and overcrowding: cholera, typhoid and so on. After years of suffering, these city problems were solved with massive community investment in water-delivery and waste systems. These have been so successful that we take them for granted, yet they remain pretty much the first order of business for urban authorities.

Now, we face new epidemics: diabetes, heart disease, respiratory disease. These, too, are a product of how we live, a function of how we have built our cities. They are in large part the diseases of inactivity and of bad air quality as a result of the city shaped to suit the car. Just as we had to invest in new infrastructure to combat the diseases of poor water quality, so we now must do the same to combat our current health risks.

The physical activity that transit and active urban transport systems offer people in their daily lives make a measurable impact on these problems, but more importantly they also enable the transformation from wholly auto-dependent car-scapes, described with startling clarity in public health literature as obesogenic, to walkable sociable neighbourhoods.

Instead of overcrowding being the great urban health threat of our age, we suffer from its reverse: too much dispersal and separation.

Motorways and a sprawling urban form are mutually reinforcing. Each creates and feeds the other. The car conquers distance, but also imposes it; when everyone is in their own vehicle, enormous amounts of space are required to accommodate these machines — at home, at work, around retail and social and cultural amenities, and of course on every road as well. This leads to everything being pushed further apart — homes from shops, shops from employment — which in turn leads to more driving to achieve anything. No more walking for even the simplest of errands because everything is now so separated. This is not only extremely inefficient but also deadly.

We are living in a new great urban age. A bigger proportion of people live in cities now than at any other time in history. People gather tightly together like this for the opportunities it offers, financially, socially, personally. So it is important we understand what a city is if we are to succeed with our only city of scale. And although New Zealanders mostly live in built-up areas, we like to kid ourselves that the urban realm is something for others elsewhere; we sell ourselves a little rural myth.

Auckland is not unique as a city. Sure, it has its specificities: its geography, its history, its culture; like every city it has its own story. But the forces that shape it — the economics of space, proximity and access — are not unique.

That Auckland is now an actual city is an important distinction. It is no longer a rural service centre, as it used to be, but an urban service centre, with an economic life, largely divorced from the extractive economy of the rest of the country, that rises and falls on its own fortunes — as can be seen by the way the city’s economic performance was unaffected by the recent downturn in dairy prices.

Of course, change is gradual. The move from overgrown provincial town to small city is an awkward one, characterised by both gains and losses, and one of the losses is the expectation that you will be able to drive easily anywhere at any time and park right in front of your destination, for free. Among the gains, however, are that the range and variety of available destinations and opportunities start to increase exponentially, offering specialised employment, education, and social pursuits.

To illustrate this with an extreme example, parking in Te Kuiti is not a problem, but then that town also offers only a fraction of the services and opportunities available in Auckland. Choosing to live in either Te Kuiti or Auckland involves making what economists call “trade-offs”, balancing the opportunities and restrictions of each place with your needs and values.

People are of course both nostalgic and optimistic about these locational trade-offs. Everybody more or less wants the best qualities of both kinds of places, so anywhere that is transitioning into a city will be characterised by complaints about both the end of the good old days and a lack of sophistication in the nascent city. This is the gangly teenager phase of urban development — annoying, but full of promise.

Auckland is now near the end of this phase. Rather than becoming a city, it is one. We need to learn to use city-shaped thinking in order to build not just a city, but a successful city.

The car eats distance, saving time, but also devours space, thereby eroding that time saving. The car and the city are essentially at odds with each other: the more we change the city to accommodate the car, the more space we allocate to driving and parking, the less it is able to fully exploit spatial efficiencies, the less city there is.

Which doesn’t mean they can’t work together. Obviously, there are cars in cities the world over, and most thriving ones have streets full of them, but they don’t depend on them alone. Looking at the streets of Sydney in the morning rush hour, it would be easy to assume that without the people in cars the city would collapse; the streets are so full of traffic. But the data tells a completely different story. Cars deliver below 14 per cent of people to the city centre in morning peak hour. If somehow every car in the city centre disappeared, it would be barely noticed, except of course it would be so much more pleasant on the streets. Most people by far arrive by train, but commuters also use buses, ferries, light rail — and cycling and walking. The economy and society there are not hostage to one system, and are therefore much more resilient. Traffic failures in Sydney do not bring the city to its knees.

Cars are great, roads are great, but in cities without other good transport options these fail both fast and slow. Traffic problems occur suddenly, with crashes and breakdowns, and more gradually by forcing an inefficient urban form and restricting choice. It is essential that choice be added to Auckland’s movement mix, so those who wish to opt out of congestion and dispersal can do so, for everyone’s benefit, including the car and suburbia lovers.

The Waterview motorway tunnels will soon open. The project — three lanes each way — will link State Highway 20 with State Highway 16, completing the urban Auckland motorway network. There will be more widening and upgrades wherever space can be found along our existing city motorways, but essentially this is it.

The end of an era. Sixty-five years and billions of dollars building a full city-wide motorway network, a system that not only has become our principal way of getting around, but one that has also shaped the pattern of the city’s development since the middle of last century, feeding its outward spread into new suburbs beyond its older tram-built heart, promising fast and independent connections across ever greater distances for everyone.

This is the logic of driving everywhere in thriving cities: the more we spend trying to make driving fast and direct, the more it will be subject to the failure of its own success. Supported by such high-quality separated highways, driving is a largely unrivalled means to get around. Until, that is, everyone is doing it.

Auckland is a small city by most standards, but the problem of traffic congestion is exacerbated by two local conditions. First, geography: the fact that Auckland is built on a tightly and permanently constrained slice of land squeezed between harbours and forested ranges, with narrow crossing points and a lack of alternative routes, unlike cities on flat plains such as in the American West.

Second, we have, for the past 65 years — that is, until very recently — focused every transport-infrastructure dollar on building roads. We have failed to build or maintain any viable alternative to driving for all journeys, and at all times, since ripping out the tram network in the 1950s.

Thus the pressure on this one complete system is disproportionate to the size of the city. It means that high-value road users, like freight and trades, or emergency services, have to compete with nanas popping down to the shops, or undergraduates in vehicles they can’t afford but also can’t avoid.

This has been a mistake and, it is worth noting, was not the advice from the North American consultants hired in the 1960s to plan a transport solution for Auckland’s future. They proposed two complementary networks, a motorway system largely like the one we are now completing, and a bus/rail rapid-transit network based on the existing rail system, with a new underground city section and extended lines including up the North Shore, to be built concurrently.

It never happened. If it had, each system would have enabled the other to function without becoming overwhelmed. The motorway system would have attracted users until congestion and parking supply and cost pinches kicked in, and the rapid-transit system would have drawn in as many people as the quality of its service could support.

The thinking behind it was that if public transport is that good — frequent, fast, flash and affordable — then more people will switch from driving, freeing up the roads enough to speed up traffic and attract some users back again, until it clogs up again, and so on. This phenomenon is called the Nash Equilibrium, and leads to the somewhat counterintuitive fact that it is the quality of the alternative to the motorway that controls the speed of the traffic there, by reducing its exposure to congestion. In other words, the best way to improve the driving experience in a thriving city is to invest in as high a quality transit network as possible.

This phenomenon is already clear on a couple of routes in Auckland: the Northern Busway and State Highway 1 on the Shore, and on the southern line and Southern Motorway. People, especially those working or studying in the city, have the choice between two ways to move on these routes, and they are exercising it.

The data supports this: In morning rush hour, over 40 per cent of people crossing the harbour bridge are on buses, which occupy less than one of the five lanes in the southbound direction, taking up less than 10 per cent of the available space. This is hugely efficient. Without the bus service, and especially the separate busway that feeds it, and with all those people driving instead, no traffic would move across the bridge at all in the morning peak.

Similarly, on the rail network, each workday last year some 70,000 trips were taken on trains (and rising). So there are up to 70,000 fewer car journeys in Auckland, mainly at peak times. And because the rail system is entirely separate from the driving network, these journeys are especially valuable to other road users.

The really great news here is that even though just a small part of our transit network is of sufficient quality to attract users in high enough volumes to keep the roads freer, what we do have works. Passenger numbers on our rail network and the Northern Busway are growing by 20 per cent every year, way in advance of population growth, and we know that by extending this quality of system we can expect the same level of improvement in the parts of the city currently without it: the parts that now offer only buses stuck in traffic as an alternative to driving, and consequently attract fewer passengers — places like Pakuranga and the north-west, and of course Mangere and the airport.

Since the electrification of the rail network and the rollout of our new Basque-built trains, a million additional trips are taken every four months. Right now that’s more than 18 million annual trips, and later this year it will likely hit 20 million. Once the City Rail Link is open, this will quickly double again, so long as we extend and support the rapid-transit network’s reach.

We didn’t build the two urban transport networks — motorways and rapid transit — concurrently, but we can build them consecutively. It is time, then, to urgently swing our institutional and political attention to this project. Only then can we hope to bring the standard of Auckland’s built environment up towards the quality of our stunning natural one — for the benefit of all citizens and the nation.

By the numbers

What can we learn from how Auckland’s public transport use has changed in the past 10 years?

Ferries are nice but not crucial

In November 2006, there were 4.14 million ferry trips a year; by November 2016, this had risen to 6.01 million. Ferry use has been growing consistently but not as fast as land-based rapid transit, so we can also expect it to continue this gradual comparative slide. Ferries are, of course, permanently limited by geography, and even with greater investment, up-zoning around wharves, better bus and bike connections (though all are worth doing), they will struggle to attract more passengers. This is why we separated them out and made them the floor of our graph: Ferries are the hard biscuit base of the Auckland public transport cake.

Buses do the heavy-lifting

The middle band of the graph relates to ordinary, “non-rapid” buses on Auckland’s roads. Over the past decade, most public transport users were on these buses. Although this proportion is shrinking because of the relative growth in rapid transit, it’s still hefty: 60 million trips out of 84 million in total, or 71 per cent as of November 2016. These ordinary buses are the main filling in the cake, providing the most heft, and they’ll continue to be even as their role morphs and shifts.

Rapid transit is where it’s at

There is no clearer lesson from the past decade of public transport in Auckland than this. People want high-quality, frequent, turn-up-and-go, moving-free-of-congestion transit. Wherever this has been delivered, particularly since the rail network was upgraded with electrification, Aucklanders have piled onto the services in consistently increasing numbers. Year-on-year growth of 20 per cent has been standard on rail and the Northern Busway as their services have approached “rapid” status (neither is truly there yet). There is no surer bet in transport provision in Auckland today than this. For all Aucklanders, and particularly drivers, the lesson to take from this is that we need to accelerate the provision of rapid transit to the whole city. This will require investment in permanent right-of-ways, but the bulk of these capital costs are one-off and of enduring value, and as they will limit the spiral upwards of costs imposed by unchecked driving demand, this direction offers better ongoing value. The blue band is the only part of the cake that can rise profoundly and have any real impact on the burdens of traffic congestion to transform the way our city operates. But to deliver it, the chefs have to get on and make it. (Enough with the cake – Ed).

Work in progress

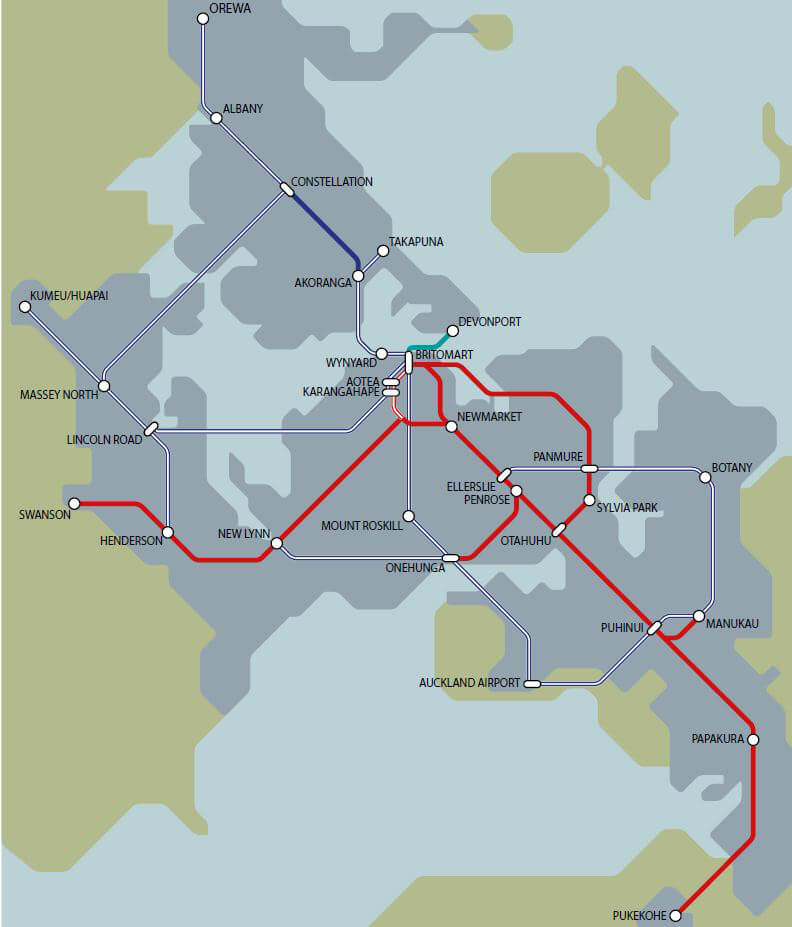

The map shows the rapid-transit network development plan for Auckland over the next 30 years. Agreed last year by Auckland Council, central government and the New Zealand Transport Agency, the Auckland Transport Alignment Project represents an important break with past thinking on resolving our transport woes. Overall, it’s a rational, necessary, achievable plan that reflects the geography and needs of our growing city.

The map’s solid lines show the existing RT system — the rail network, the Northern Busway and the Devonport ferry.

What’s happening now and what must happen next.

The CRL, at last

The City Rail Link is under way, not only for the city centre but for everywhere served by the rail network.

Out east

The rapid-transit bus service from Panmure east and south is close to its next stage — fast buses from Panmure to Pakuranga — as part of the Auckland Manukau Eastern Transport Initiative (AMETI). On to Botany must surely follow soon after. The train from Panmure is so fast that using buses to extend access to that station for the 100,000-plus people across the Tamaki River needs to be a top priority.

And west

The Northwestern Busway is planned, but work has yet to start.

The Dominion Rd fix

The proposed Dominion Rd-Queen St light rail will provide much-needed capacity along a busy corridor and connect the fast-growing Wynyard Quarter to the city, ferries and all three city CRL stations, plus major bus terminuses.

Taking flight

A rapid-transit connection to the airport has been the most desired public transport project in public surveys for years, if not decades. Government agencies, it has to be said, have been less than helpful about this, but have now woken up to the fact their preferred system —driving — can’t function reliably without relief from a high-quality alternative. Start with a link to Puhinui Station, where there are already trains in each direction every five minutes, or through (and serving) Mangere.

Buses first

Crosstown and Upper Harbour enhanced bus priority is happening (for example, buslanes, high-frequency, branded services, hopefully intersection priority); the Pakuranga Highway to Howick route needs to be added to this. The isthmus is missing a crosstown route along Balmoral Rd — not everyone is heading to town.

Another crossing

A new transit-only harbour crossing, either twin tunnels or a new bridge with added cycling and walking paths, would take the proposed Dominion Rd-Queen St light rail across the harbour from Wynyard Pt and up the busway, with a branch line into Takapuna. Either way,the speed and quality of travel from the North Shore to the city would be so good that the number of people using it would keep traffic on the bridge flowing for decades, and most Shore buses would be replaced by the new rail service, freeing up city streets and the bridge itself.

Light relief

The number of light-rail vehicles serving the North Shore from the city should be double the number required for Dominion Rd. This would open up the possibility of another destination south of Karangahape Rd for light rail. The Northwestern Busway could be converted to light rail to accommodate this.

WHAT ELSE IS ON OUR WISH LIST

Electrification of the rail line to Pukekohe, enhanced ferry services and local bus and cycle ways converging on all rapid-transit (bus and rail) stations, all funded within current transport infrastructure budgets through the opportunity offered by the end of the motorway-building era. The key is to unlock the “network effect” as soon as possible, to complete as much as possible as quickly as possible. This enhances and accelerates the value to the city and to the road user, reducing the costs of traffic congestion and doubling our city-wide transport systems.

What is rapid transit?

Rapid transit (RT) is faster than ordinary public transport and has other advantages that make it a viable alternative to driving.

High-quality services are typically found in the better rail systems of cities around the world, but similar standards are possible with buses and ferries, too, if they offer a separate right-of-way, like a rail line; a vehicle every 10 minutes or less; fewer stations, served by local buses, cycleways, and parking; a predictable route; comfortable, clean vehicles and stations; a seven- day service that starts early and ends late; a wide network.

Auckland has a nascent rapid-transit network in our rail system and the Northern Busway, which are driving a 20 per cent annual rise in public transport use. The busway has services every few minutes at peak times, the buses are newer and the stations are good. But the right-of-way is incomplete, especially over the harbour. The rail network, while out of traffic on its own system, offers turn-up-and-go frequencies only in peak hours, slipping to 20 or 30 minutes between trains at other times. Evening and weekend services are dismally infrequent.

Yet in many ways all this is good news, as it shows that meeting even half of the conditions for true rapid transit helps. As demand grows, further service improvements can be justified, which will be rewarded with more people using the services.

It also means other systems can be used to fill the gaps in the RT network: new rail lines where demand is high and it fits with the current network, like the City Rail Link; busways to build demand in places with no RT, like the Auckland Manukau Eastern Transport Initiative from Panmure through Pakuranga; light rail where there is a need for high capacity but no space for a separate rail line (eg, Queen St to Dominion Rd).

The strongest RT case is for another harbour crossing — either a new rail and cycling and walking bridge, or a pair of rail tunnels.

On the move with technology

The rise of driverless vehicles may well bring a boost for public transport – and give some power back to pedestrians.

We live in an age of profound technological change, and this is reshaping our city. Alongside technological changes are social ones, too, transforming how and where we live, work, study, play and move.

Global mega-trends lead to local mega-change. Auckland, like many cities worldwide, is in the middle of a rebirth: the return to the city, with a boom in inner-city living and employment reversing the flight to the suburbs of the mid-20th century. This social shift is linked to the massive reshaping of social interaction through digital technology.

One big looming change sure to reshape urban transport is the rise of driverless vehicle technology. Exactly what the impact will be is an interesting question.

A major claim for this technology is that it may render private vehicle ownership obsolete; we can avoid the considerable cost of owning, insuring and storing our own cars (parked, on average, 96 per cent of the time) and instead just summon a taxi-like robot-car to pick us up and drop us off, at a much lower cost because of the absence of the driver and the efficiencies of sharing and Uber-style booking processes. This is especially promising for the vision-impaired, the frail elderly, and even kids, along with other non-driving groups.

The world is clearly some way off from this scenario, and faces various hurdles, not least of which is people’s attachment to their cars and pleasure in driving. But if the economies are big enough, such a change will likely be unstoppable over time. So if driver-less technology might break our private car addiction, what is it likely to do to public transport? Some claim it will render that obsolete, too.

On closer inspection, the evidence for this is poor. In fact, there are strong arguments that driverless technology is more likely to not only lead to a continued boom in public transport in cities, and accelerate the already current trend for reducing the volumes of cars in urban centres, but also reduce the value in building more and wider highways.

One of the main promises of autonomous vehicles (AVs) is that they will increase the capacity of roads by enabling very safe, very close following. This is through a process where each vehicle connects invisibly to the others on a road and locks them together even at high speed. Called “platooning”, it offers the prospect of more vehicles per lane per hour on congested roads — more safely, with fewer disruptions through crashes and other inefficiencies caused by human vehicle control. In that case, do we really need to double the width of a motorway, when new car technology will double the throughput without us having to lay one more metre of asphalt?

Arguably the greatest promise of the AV is a radical improvement in safety. In New Zealand alone, around a citizen a day is killed on our roads. AVs offer the prospect of largely ending this terrible situation.

How will they achieve this? By faultlessly following every road rule, including speed limits, by being constantly aware of every possibility of harm, and never moving without being able to stop or evade the cause of the danger. These robot-cars will be programmed to protect human (and animal) life before all other considerations. They’ll have to be, right? Or some corporation is going to be sued out of business for making a machine that chose to kill someone’s family member. Manufacturers are also likely to be under pressure to make their ’bot-cars courteous, giving way via a blink of a light, or something, to pedestrians and other road users, at every turn.

So while AVs will almost certainly increase the speed and efficiency of cars and trucks on the already vehicle-only environment of the highway, in the more complicated world of the busy city street they are unlikely to get very far. All any pedestrian will need to do, and not even consciously, is appear like they might step onto the road and the all-seeing hyper-cautious ’bot-car will stop. On any street with more than a few pedestrians, or people on bikes, cats or dogs, or kids kicking a ball, these machines will not move fast, if at all — much, no doubt, to the frustration of their occupants. Many will probably get out and walk rather than suffer the immobility of these good-hearted wheeled pedants.

In fact, the possibility this opens up for people to entirely take back pedestrian-rich city streets is very strong. It is only because we currently have no faith that a human-controlled vehicle will stop at all for us when walking that we keep out of their way now. With AVs, people will be back in control of the street. And the more unpredictable the other street user is likely to be — a bunch of teenagers, a skateboarder, an older person — the more cautious the machine will have to be. Remember, these rolling computers will know exactly the odds of a freak event occurring.

There is a simple reason we go to the bother of running trains, trams, buses and ferries in cities: spatial efficiency.

Cities run on the economics of space; this is the engine that makes them tick. If this wasn’t so there would be no tall buildings, micro-apartments, or underground trains and carparks. Traffic congestion is a function of the spatial inefficiency of cars as urban transport: they take up too much space for the number of people they move. AVs may help increase average car occupancy, which would improve their spatial efficiency, but it is far from clear that they will. Especially as they are likely to lead to a great number of new empty journeys, going to get people (or even things: Forgot your homework? Send a ’bot-car!). So, instead of raising average occupancy from the current 1.2 people per car, AVs may lead to it dropping below one, making urban traffic congestion worse.

What they can and probably will do, however, is replace infrequent transit services in lower-density suburbs. This is good for public transport providers, saving money on loss-making bus services at the city fringes, and great for non-drivers, who gain point-to-point rides in their dispersed neighbourhoods at reasonable cost.

It’s likely one of the prime destinations for these AV users will be the neighbourhood transit station, when users want to go further than their local area. This is already the case with current ride-share systems, as shown by Uber data from New York, where a high proportion of journeys are to train stations, especially in the suburbs. The AV — like today’s car — will work best in low-density dispersed environments, while spatially efficient, high-volume transit systems will continue to work best where they do now, on high-demand routes serving the high-density centres.

Reinforcing the increased value that new technology is likely to bring to urban transit is the fact that driverless technology is not just coming to small passenger vehicles like cars, but also to big transit vehicles, too: trains and buses. And the cost advantage of removing paid drivers makes the economic imperative of getting driverless buses on the road even stronger. Around half the cost of running a bus is associated with the driver. Driverless trains already run in places like Vancouver and Hong Kong, as it’s easier to run driverlessly on a fixed rail system than the open road. The savings from this are so great that the Vancouver SkyTrain system has reported an operating profit every year since 2001, while making more than 200 million annual journeys, to the enormous benefit of that city’s economy and its productivity.

So driverless tech, far from making public transport redundant, is likely to focus, enhance and increase its value and use while lowering its cost base. Transit services and for-hire AVs are likely to be integrated into one system, all organised and paid for via one smartphone app. This is the holy grail of new technology in urban transport, and is being feverishly pursued in tech hubs everywhere — a model known as MAAS: Mobility As A Service.

The result for cities that prepare well for this pattern is going to be pretty good: vibrant city centres, largely carless, served by frequent and mostly self-financing, modern, electric transit underground rail and mostly traffic-separated light-rail systems; highways much more efficiently filled with electric self-driving cars and road freight; suburban streets busy with for-hire low-cost electric AVs, along with tradies, delivery vehicles and buses in dedicated lanes on arterials — all feeding a city-wide rapid-transit network connecting all the centres.

Oh, and separated bike lanes everywhere, as this humble machine, electric or otherwise, is still the killer app for local access. As long as there’s somewhere safe to ride.

I think we’d all take that city of the future, wouldn’t we? In which case we’d better start building it now.

Great rides

Float on a ferry

Ours is a harbour city. Want a great experience? Catch a ferry in Auckland, especially on a lovely day, even better at dawn or dusk, but anytime really, so long as the queues aren’t too long and the boat too full. These are truly among the greatest cheap little excursions available in any city in the world. Fortunate indeed are the people who have these trips as part of their regular day. The only downside is that these services are by definition available only in certain places, which isn’t to say more couldn’t be done to expand and improve them, but simply that they will always be a minor part of the mix. The pick of the lot is the classic Devonport-to-downtown run, something I always take visitors on.

Ride a new train

These are fantastic — smooth, silent and clean, swooshing through the city unencumbered by traffic. The best trip is across the Orakei Basin at high tide on the Eastern Line, not just because the view is gorgeous but also because this is our newest main line (built in 1930!), so it is straight and smooth and doesn’t have a single level crossing to slow the journey. Even better is the range of destinations it covers on its way to the new Manukau City Station, from Middlemore Hospital/King’s College to Sylvia Park to the diversity of Glen Innes and Orakei. Because of the straight route through tunnel and over causeway, Glen Innes is just 12 minutes from the city and Panmure 15, a speed that can’t be matched by road. And because of the variety of places on the line, each trip is usually filled with a variety of people. And always, in my experience, harmoniously.

Catch a double decker

The best seat on a double decker bus is up top at the front, with a royal view. Take a ride across the harbour bridge — you get a much better vantage point than at car level — and feast your eyes on the city, the yachts on the Waitemata and the Meccano-type bridge super-structure. This is the only route where the bus has its own right-of-way, like a train, even if not on the bridge itself. Take the same seat for a ride through Mt Eden. It’s a slower trip because of the intermittent bus lanes, but the vistas are often charming: the maunga swinging into view, the variety of the buildings and the busy centres.

This is published in the April- May 2017 issue of Metro.

Get Metro delivered to your inbox

/MetromagnzL @Metromagnz @Metromagnz