Apr 3, 2019 Transport

The City Rail Link is one of the biggest infrastructure projects in Auckland’s history. But some myths persist and many people still don’t appreciate the scale or the benefits of the project. Hayden Donnell explains how this huge underground undertaking will help connect the city and improve the lives of Aucklanders right across the region.

This story initially appeared on OurAuckland and is shared with permission.

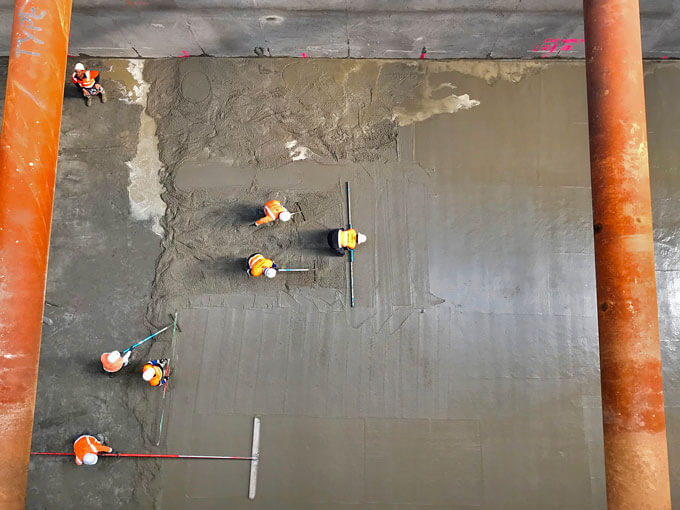

A transformational undertaking

The City Rail Link, two 3.45km-long tunnels up to 42m below the city centre, is the single most transformational undertaking in the history of Auckland’s transport. When complete, it will reshape not just communities in the city centre, but along every rail corridor in the region: from Orakei to Otahuhu in the east; Grafton to Swanson in the west; Penrose to Pukekohe in the south.

So why don’t more people know that? CRL chief executive Sean Sweeney admits branding has been part of the problem. But another factor was the miseducation, or sometimes wilful ignorance, of the project’s critics, he says.

“If we had a clean sheet of paper and I was asked to name it, I’d probably call it Auckland Metro,” he says.

“But you can wilfully distort any name if you want to.”

The PR problems started when the City Rail Link was little more than a concept on some planning documents. Opponents of the project sought to paint it as a pointless waste of time and money, some kind of Sisyphean nightmare disguised as public transport, a white elephant that would saddle Auckland with massive debt while achieving nothing. People would board a train, check their texts, and arrive back where they started half an hour later, critics said.

In an interview with John Campbell on TV3, then-Transport Minister Gerry Brownlee called the link a “very short little loop that goes around”. Others simply rolled their eyes and complained about then-mayor Len Brown’s “train set”.

Benefits across Auckland

The narrative persisted even after the project was officially named the City Rail Link. Even now, many people still don’t understand the project’s true scope. They may think it’s a happy development for the residents of Albert Street or Karangahape Road.

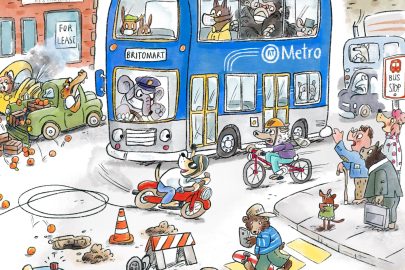

But here’s what it actually does: above all, it stops Britomart, Auckland’s busiest rail station, being a dead end.

Right now, trains arrive in the city centre, then reverse out past a queue of other engines waiting to get in. The CRL will allow them to flow through to other parts of the city via new stations at the corner of Wellesley and Victoria streets and Karangahape Road.

That might not sound like much, but its impact is profound. Rail frequencies will increase markedly everywhere in the city. Instead of every 10 minutes in peak times, trains will come every five minutes on just about every line. Travel times will drop substantially across the network, but particularly in places like Mount Eden, which will be within a 10-minute journey of Britomart.

“In simple terms, it’ll more than double the number of people who can get into the central city and out again,” Sweeney says.

“The numbers that we see show that an extra 40,000 people can get into the central city per hour, which is equivalent to 16 lanes of traffic.”

He’s baffled when people argue the project’s $2.8 billion cost would be better invested in roads.

“This is 16 lanes of traffic we’re talking about,” he says. “What I said to someone was, ‘Which suburbs are you going to demolish to build this superhighway?’”

A catalyst for local development

Those improvements are important, but they still don’t fully illustrate the wider effects the increased connection will have on Auckland’s communities. The CRL is expected to be a vital catalyst for town-centre redevelopments like those taking place in Henderson, Onehunga or Panmure.

A recent analysis by Auckland Council Chief Economist David Norman showed that in the city’s eastern suburbs, houses within 260m of a rail station are priced 19 per cent higher than those 500m away or more. Housing and commercial space near reliable and rapid public transport is more desirable.

Auckland Councillor Chris Darby says that means places like Henderson have the potential to become thriving centres when the CRL is completed. “When we’ve made rapid-transit investments, people have actually flocked to where they can live in proximity to that rapid transit,” he says.

Sweeney is equally enthusiastic about the CRL’s potential to change not only Auckland’s transport, but its culture and urban fabric. “This is the public transport project that will transform Auckland. The development opportunity it brings. The accessibility it brings. It is fundamentally what will enable Auckland to become the city that it wants to be. It will help Auckland grow up.”

Pretty good for a little rail loop that goes around.

This story was first published on Our Auckland?

Follow Metro on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and sign up to our weekly email