Sep 5, 2023 Sport

Robin Tait was a New Zealand sporting Icon. A Commonwealth record holder getting his gold medal from Princess Anne. An athlete with everything going for him. Robin was massive. A giant on the field. And a party goer and an outrageous extrovert — a legend of bad behaviour. Tait’s other life was dark, depressing and drug fuelled. A walking medicine cabinet that would slowly start bringing his life to a horrific end.

Robin Tait had everything going for him. Friends, fame and outrageous popularity with fans and media alike. This country’s love affair with Tait was unfailing. A gentle giant with prolific addictions that no-one seemed to be able to control.

Robyn Langwell, a Metro staff writer who would go on to be the founding editor of North & South, followed the dark and torturous trail through New Zealand’s sporting elite to track down the horror story that unfolded in the search for the real Robin Tait. A graphic and confronting piece of superb journalism from June 1984

Bob Harvey

The Archivist

–

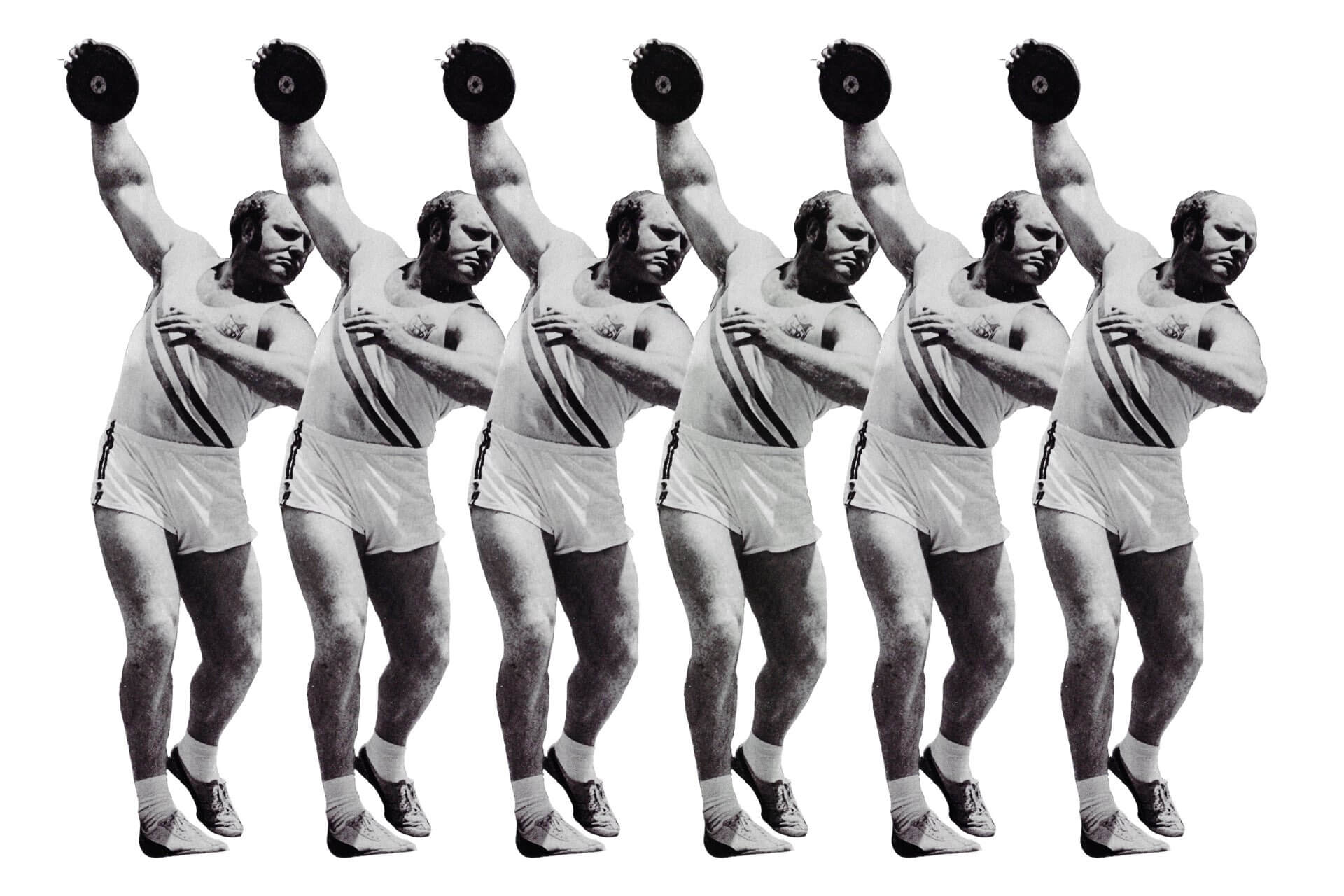

In the early days of 1974 the southern city of Christchurch hosted the 10th Commonwealth Games. On one January afternoon of eye piercing light and high temperatures a group of bear-like men lumbered out onto the green of the infield. The discus throwers. No one stands out. All are built like barns, all are well over six feet tall and a few weigh over 20 stone. Their event has its origins back in the history of the Ancient Greeks who hurled discs of wood or stone weighing 8 or 9 pounds. These men will launch projectiles weighing half that but they will throw over 60 metres.

New Zealand’s main hope is Robin Tait. With his burly build, stern look of concentration and aggressiveness as he psyches himself up, he is a forbidding and impressive sight, but his first attempt is a no-throw and his second lands rather pathetically just short of 55 metres. He curses himself long and loudly. On his pre-Games form the best he could hope for was the bronze medal. Now even that looks doubtful. The third of Tait’s six throws arcs through the hot air. There is a track race under way at the same time and the runners impede the view for many people in the stand and so they miss the perfect discus throw, the throw Robin Tait has spent 15 years trying to achieve. All the years of training come together as the discus leaves his hand. Former rival Les Mills, sitting commentating in the stand, remembers a flash of excitement: “You were aware from the moment it left his hand that it was going to be a bloody beaut, the sort of throw a thrower dreams about. It just all came together for him at that time on that afternoon.”’ The white flags go up to mark a good throw.

The tape reads 63.08 metres-a Commonwealth record. Tait sits back, rips the tab from a beer, guzzles it deeply and refuses to throw again. He is arrogantly defying his competitors to beat him. None can. There’s a photograph of Robin Tait getting his gold medal from Princess Anne that day, and there’s a strange look on his face, half faraway dreams, half sneer. That look means a lot when you go searching for the character of this unusual man. For many athletes a Commonwealth Games gold medal would have been a beginning, a means of opening doors to the future, of a good job, prosperity and community respect. Not for Robin Tait. Ten years and just a few weeks later, he is dead at 43, broke and possession less. Tait died, according to the post mortem report, of pancreatitis, but as we shall learn, that was merely what finally killed him. There were two distinct sides to Robin Tait.

All who think they knew him agree he was larger than life, the life and soul of any party, one of the funniest men alive. He also regularly suffered deep depressions and intense migraines, he failed to rise to any challenge outside discus throwing; in fact he failed miserably to cope with everyday life. There were many people who told me not quite the whole truth in my search for the real Robin Tait, others made guarded threats and a lot more simply refused to talk at all. Perhaps they were too close to the fire that finally burned out Robin Tait and they are scared. This then, in spite of the phone calls that were never returned, the threats, half-truths and diversions, is a story about the murky world behind high performance sport, the pressure of striving for perfection, the taking of drugs in that pursuit … and the cost.

St Mathews in the city is a cold, grey place that puts you in mind of death on this end of summer afternoon with its light filtering through the stained glass windows as they play one of Robin Tait’s favourite songs. The words of Larry Weiss’s Rhinestone Cowboy are eerily apt …

There’s been a load of compromising

On the road to my horizon

But I’m going to be where the lights

Are shining on me …

The mourners are a very mixed lot. Some wear dress shoes and formal sports blazers, others-running shoes, jeans and leather jackets. One or two are wearing chains. There’s a tattooed lady. A few grey and blue suits. The blue carpeted floor is littered with flowers. On top of the coffin someone has placed a discus. It occurs to me that the coffin doesn’t really look big enough to bear the hulk that was the Robin Tait I remember carrying our flag as team captain at the Brisbane Commonwealth Games just 18 months ago. Then he marched, arm stiff, hoisting the flag single handed along the length of the back straight. At the funeral there are plenty of eulogies from Tait’s sporting contemporaries, plenty of gloss, but the truth about his life is swept under that coffin. There’s something strange about the mood, something I can’t quite grasp. There’s levity and people are laughing; it’s largely a funeral without tears. They carry him out, his famous buddies, footballers Greg Denholm and Greg Burgess, fellow thrower Walter Gill, top cop Ross Dallow, sports entrepreneur Les Mills and runner John Walker knees buckling, to the theme from Chariots of Fire. Afterwards, outside, the athletes discuss track times and the Olympics while the footballers remember some of Tait’s more bizarre antics in various bars. Only his mother, sisters and daughters weep. None of these people really knew Robin Tait, they just inhabited small sections of his life.

Robin Tait was born in the Dunedin suburb of Corstorphine in 1941. Home was a state house his parents Doug and Min later bought to accommodate their six children. It had three bedrooms, a boys’ room and a girls’ room. Space was short and Robin practised his weight lifting in the kitchen with such vigour that the floor crept two inches away from the wall. Glenda Cutler, eight years younger than her big brother, remembers him being a disruption to the family, prancing around the house flexing his muscles forever being absent or late for meals spending hours out in the bone-chilling cold of Tahuna Park, even in winter in the keen and frosty air with ice on the ground, practising his throwing. Sport was very big in this working class family. Father Doug, a fabric cutter who worked his way up to being a warehouse manager, was a keen footballer. Older sister Elva a New Zealand basketball rep and the other two girls and two boys all played sport. Even in his early teens Tait was a big boy, growing quickly to over six feet and 15 stone. He ran, played basketball, long jumped and threw the discus and shot with obsessive determination. He was educated at Taieri High School in Mosgiel where although he never starred academically he was made a prefect.

Even then he was up and down emotionally, spending large periods of time on his own, training and brooding. He had trouble working out words he had never seen before, a problem he tried to hide throughout his life with disastrous results. It was a failing some of his more learned friends later recognised as dyslexia, although he never discussed it with them. That he suffered from dyslexia explains a lot though. Like Tait’s continued inability to remain in jobs got for him by friends good jobs with company cars to drive and time off for training. The first time he was asked to write a report or file an inventory of stock, he was finished. Tait’s work record was always erratic and patchy. His sport was everything and a job was something he worked around training while company cars were used to get from one training ground to another.

At 18 Robin Tait joined the Army. It was 1959 and he was the New Zealand junior shot put champion. It was to be a good two years at Burnham camp near Christchurch as a PT instructor. In many respects it was the perfect job for Tait. The Army suited his personality and provided the two things he desperately needed, an escape from all responsibilities and a constant stage on which he could be physical. The service provided him with a gymnasium, food, clothing and a barracks full of young men to drink and train with. There are people who say that if he’d stayed in the army he might be alive today. Instead he crept back to the bleakness of Dunedin where the winter nights come down cold in the mid afternoon and the easterly winds drive people indoors in midsummer. Tait just went back to a succession of odd jobs and late nights throwing into the inky blackness and bitter cold of Tahuna Park, his one aim in life to become top in his sport in New Zealand. It was the only thing that mattered.

He told Auckland physiotherapist Graeme Hayhow this at their first meeting. They were both just 20 and Hayhow remembers the night vividly, it was the most exciting party of his life. He was training at Otago University at the time and had been invited to a varsity party. Tait, already over 20 stone, and one of his cronies, a 19-stone psychiatry student called Graham Pohlen who went on to become an Otago lock forward and All Black triallist, were trading tales around a table in the middle of the lounge of a first floor flat with a group of equally huge rugby friends when the floor fell in. Hayhow remembers jumping out the window to safety. Tait shared the flat with Pohlen and dental student Keith Nelson, later an All Black and now a successful Auckland dentist. The trio drank their way through a crate of milk and ate three pounds of cheese a day.

Even in those days Tait who failed School Certificate and who had trouble with words, was frequently out of his intellectual depth. He compensated by steering away from people he characterised as ‘wankers’ and by playing the court jester, the big man who always made people laugh.

It was at an Otago University party that Tait met his first wife Cathy Tait. She was a trainee home economics teacher. They were quickly married. It was a brief marriage but it lasted long enough to produce two daughters, Karen now in her early twenties and Nicky 19. The three women were the first major responsibilities Tait was presented with in life and he shirked them almost immediately.

He fled to Auckland in 1965, ostensibly to find more sporting competition. Pohlen aided the escape by organising a temporary home with Auckland Star journalist and New Zealand decathlon champion Roy Williams and his wife in Te Atatu. Tait stayed with the couple only a few months but in that time Williams arranged his first job here as a travelling rep for Rothmans. He also introduced him to the sporting nerve centre that in those days was the Western Suburbs athletics club at Grey Lynn Park. In the early sixties Western Suburbs athletes won more New Zealand titles than any other club in New Zealand. In 1965 they held more than half the national titles.

For Tait it must have been like finding paradise. A club of superstars and not a wanker in sight, a place where he could fit in and just talk and work at sport with people like Les Mills, Dave Norris, Ross Dallow, Doreen Porter, Malcolm Hahn and Roy Williams. Dave Norris, then the national triple jump champion and now principal of Glenfield College remembers: “It was a sweatshop, a marvellous environment of iron wills and dedication to sporting excellence. We all just hung out there together and worked at it. It was sweaty, gritty, and good.

Les Mills, then a home appliance and footwear retailer recalls the club as a sporting phenomenon “the sort of thing that has happened just a few times in New Zealand. It’s tied up with the energy created when you bring a certain mix of people together. It’s called synergistic energy-magnified energy, group energy. It’s the same thing that happened with Lydiard during the late fifties with his group of Halberg, Baillie and Magee.”

For the next seven years Mills and Tait were to be hard and sometimes bitter rivals. Mills says now that they were never close friends but neither were they enemies. Others will say that enmity existed. Certainly Mills was good to Tait. He rented him his house, just over the fence from the Western Suburbs club, and when Mills began running his own gym, after returning from the United States, Tait trained there at mates’ rates, and also at the home gym that Mills had built at his new home on the beachfront at Pt Chev. Later in 1978 when Tait was broke and training for Edmonton, Mills would pay his butcher’s bill $600 over four months.

There was no love lost from Tait’s side though. One of his happiest moments, he told friends, was when he beat Mills in the 1965 national discus championship. He saw himself as the boy from the wrong side of the tracks in Dunedin, in the old training shoes and moth-eaten track suit downing the moneyed athlete fresh back from a two year stint at an American college.

It was at this time that Tait first began to use anabolic steroids, the drugs that some people call muscle fertilisers. Internationally, anabolic steroids have been widely used in strength sports since around 1958. These drugs are synthetic derivatives of the male sex hormone, testosterone, and were devised by chemists for body building and strengthening chronically ill patients, usually the elderly. The anabolic steroid increases the size of the muscle fibre, which gives an increase in muscle bulk, and thus an increase in strength.

Just what anabolic steroids do for the normal human frame is a question that brings differing answers from athletes and the sports and medical establishments. According to mainstream medical opinion the drugs are both ineffective and hazardous but athletes insist that they help increase weight and muscular strength. Whatever, steroids soon featured heavily in the American sports drug sub-culture that took in body builders, footballers and strength athletes such as weightlifters, shot putters, hammer and discus throwers. So much so that by the late sixties victory in the Olympics in strong man sports came down to which country had the best team of doctors and chemists.

Anabolic steroids have a murky history. The first use of male steroids to improve performance was in the Second World War when German troops took them before battle to enhance aggressiveness. After the war steroids were given to the survivors of German concentration camps to rebuild body weight. Their first use in athletics is alleged to have been by the Russians in 1954.

Besides its growth-promoting effect testosterone induces male sexual development such as deepening of the voice and the hirsuteness which accounted for the masculine appearance of Soviet women athletes during the fifties. Although there’s nothing illegal about taking these drugs, they were banned from international sport in 1966 and random testing for them was begun at the 1968 Olympics. The International Olympic Committee medical commission in its doping booklet warns: “Anabolic steroids can severely harm the health, causing liver and bone damage, disturbances in the metabolic and sexual functions, and in women virilisation and menstrual upset.”

In New Zealand Dr Noel Roydhouse editor of The New Zealand Journal of Sports Medicine and team physician at the Edmonton Commonwealth Carnes and Dr W. Mayne Smeeton, chairman of the Federation of Sports Medicine doping subcommittee admit warily that anabolic steroids and amphetamines are used regularly, but neither ls prepared to estimate to what degree. Roydhouse believes “some misguided doctors provide steroids to athletes but says the question of the use of amphetamines by athletes is “a very grey area”. In this country there is no drug testing programme except in the annual Dulux cycle race.

Anabolic steroids are provided free on Social Security if they’re for the treatment of disease but a doctor can prescribe them without restriction, his onIy obligations being moral ones. Roydhouse acknowledges that anabolic steroids have a double effect on athletes, not only building body strength but increasing aggression which increases the drive and motivation to train harder. However, Roydhouse says the known side effects of sterility, increasing impotence, shrinkage of the male organ and an increase in the hardening of the arteries which could lead to an increased likelihood of heart attacks, and masculinisation of females, should be enough to put even the keenest achievers off.

Dr Smeeton said “They take a month to start working on the system and can increase body weight by a couple of stone in just a matter of months. An athlete can stop using them a good month before a competition and still feel the benefit. The bulk he has put on takes a lot longer to disappear. All of the detection systems in the world are not going to be effective when winning is concerned. The determined athlete is a shrewd athlete. “We believe that the taking of any drugs to enhance performance is cheating, and it is particularly worrying where young people are looking to sportsmen for an example and see drug taking gradually becoming an acceptable code of behaviour. ”In principle it is becoming an important issue for us to protect our athletes from themselves.”

This was what Robin Tait was getting into. He was by now travelling overseas and mixing in international sporting company. Drugs were an integral part of that scene and he was quickly into it. He always drank more, ate more and trained more than everybody else and now he took more drugs than anybody else. Already emotionally unstable with his depression and the dyslexia be insisted on hiding from everybody, Tait now got into lethal cocktails of drugs. Friends remember him forever gobbling pills and having a travelling medicine chest that surpassed those of the team doctors.

Dave Norris remembers sitting down to a decent lunch of steak, salad and fruit at any one of the six Games’ villages he stayed at as a competitor and official and seeing Tait produce a plastic bag of 12 or 14 pills and throw them all back. Tait was a junkie in the sixties before the word was fashionable in the seventies. He had five doctors he regularly consulted for the same “sore ankle”. He had pills coming through the mail, pills from a tame chemist, pills from the warehouseman at the drug company, vitamin pills, aspirin, steroids, uppers, downers. He always had a bag that contained the lot. He devoured information from overseas about new sports medicines and techniques. He was a faddist who veered from raw eggs to amphetamines. ”He liked to try everything he heard or read about,” remembers Norris. ”He tried them all at once, a hotch potch. There was no method in his madness and he never really knew what intake or new training method was helping his body.

Tait also began to dispense cure-alls to fellow team members. He often joked that he knew more about medicine than the doctors and that one day he would write a sport medical textbook. But the pills he took only deepened his depression and made the wild swing of his moods more out of control, heightened his insecurity and lead to very strange behaviour.

As far back as 1962 Tait did things normal men wouldn’t do. He ignored rules, regulations, moral and social boundaries. At the 1962 Commonwealth Games held in Perth, both Tait and Mills should have won medals in the discus but Tait finished fifth and Mills sixth. Mills, who was troubled by injury at the time, remembers being terribly disappointed with himself and determining to do better next time. Tait, on the other hand, apparently unable to cope with his failure, went missing from the village for five days and only returned in time to climb on a bus bound for the airport and home.

Throughout his life Tait admired women and to quote a friend ”considering what a big ugly prick he was he was very successful.” However his behaviour in their presence was hardly becoming. Even in the early days down south when he was still a junior Tait liked to shock. In the late fifties at dances in the local hall on a Saturday night he would arrive always with a booming stentorian laugh and announce that he was here, full of babies and ready to share them.

Later the vulgarity increased. Touring overseas wearing the New Zealand blazer and silver fern he would be approached by women wanting a chat and his autograph. He would comply and then turn on the innocents inquiring “Excuse me ladies, do you fuck.” He would sit at a crowded restaurant with two dripping, pale and floppy oysters dangling from his nostrils. His sexual exploits in intimate detail were regularly revealed in bar room huddles and so was his notorious penis. It or its dimensions were laughably legend in athletics. ‘The 10 ton of dynamite with the two inch fuse’ was how one acquaintance put it. This condition may well have been self-inflicted as two of the side effects of prolonged anabolic steroid use are atrophy and shrinkage of the male member and impotency. Born like that or acquired through chemical abuse, Tait was not happy about the size of his penis. One of his more revolting tricks at parties was to beat his penis with a beer bottle, so hard and convincingly people vomited.

Tait’s outrageous behaviour wasn’t appreciated by athletics administrators either. He was often reprimanded for his behaviour and was frequently called to account for himself before the Auckland centre of the New Zealand Amateur Athletic Association. In most areas of his life he would run a mile from a fight or any sign of violence, but he seemed to enjoy baiting officials. At the national championships in Auckland this year, just days before he collapsed, Tait had to be led away by the hand and put in a car by his doctor after he had hurled a beer can into the crowd, hitting women. Aggression probably fed by depression at losing his title, steroids and amphetamines. Once in the late seventies after some petty battle with a senior NZAAA official, Tait signed a child’s programme at an international track meet with the addition ” … is a fuckwit”. The child took the programme to his parents and they took it to the NZAAA.

But Tait was a minor sporting legend, at least to athletics fans, and as long as he could still perform, the selectors had difficulty leaving him out of national teams. At the Brisbane Commonwealth Games, in spite of his behaviour, Tait was made team captain, in part, says Dave Norris, the team’s senior athletics coach, as a tribute to the fact he was representing New Zealand in his sixth consecutive Commonwealth Games, something no one else has done. ”I think that appointment was probably the greatest moment of his life, after his gold medal,” says Norris. “It was also a hell of a risk. It was a two week gamble to try and tame the beast. There was a whisker between it being a good decision and total madness. But the gamble paid off. He was excellent and the team benefitted from his captaincy.”

In the sixties Tait was an extrovert, noisy, fanatical competitor, but going into the seventies, and certainly by the eighties, his friends began to notice the start of a decline. ”Like a Mack truck barrelling around the country out of control” was how one put it. ”I did five or six overseas trips with him,” remembers Dave Norris. “And there were some terrible moments of deep depression where he really needed dragging off his knees and putting on his feet. He was undergoing personality problems. It really was the start of a form of madness. I think he needed psychiatric help, but as far as I’m aware, he never had any.

“I have vivid memories of being sat in a small room in a Games village somewhere talking to an incoherent Tait, babbling like a child that he couldn’t compete, that he wasn’t well, that he wasn’t strong enough or good enough. His depressions didn’t, at that time, seem to be on a grand scale, they weren’t about the state of his life as a whole, and they were about more immediate things of the moment, the pressure of the coming competition. He would have been training for it for months, but then he would wake up on the morning and not be able to face it. ”There were lots of those moments, Edinburgh, Edmonton, Christchurch. People bore with him, myself included. It’s hard to pinpoint why, if it’d been a kid you would have just said shape up or ship out; but he was so quick-witted, so funny, even when he was very down he would throw in a joke, some wit, and you had to smile at him and carry on picking up the pieces.”

Probably the greatest friend Tait ever had was his second wife Gay. Another teacher who he met and married in Auckland in 1969. She gave herself entirely to his needs for three years, supporting him emotionally and financially. She was the one who got him together for that sunny afternoon in Christchurch in 1974, working two jobs as a teacher at Cockle Bay School and behind the bar at the Ponsonby Rugby Club after school.

In the months coming up to the 1974 Commonwealth Games Robin and Gay Tait lived in a rented farmhouse at Whitford where Tait had laid a throwing circle in the back paddock and built a makeshift gym in a shed. He was out of work but Gay earned enough to feed them both, working behind the rugby club bar while Tait lounged on the other side, drinking and telling stories. While his mates from the early sixties hung up their medals and moved on to other things Tait boozed and caroused on. Dave Norris went up through the education hierarchy, Ross Dallow became chief inspector of the operational staff of Auckland’s police force, Les Mills is probably New Zealand’s first sports millionaire and Roy Williams is a respected sports journalist. But Tait was the little boy who never grew up. As he kept on competing, his training and drinking mates got younger, his grip on reality looser and his behaviour louder and less acceptable.

People who were close to Robin Tait say that he began to really go downhill emotionally when Gay left him in June 1975. She’d given everything to get that gold medal at Christchurch and she wanted something back -a house, children, a husband who was prepared to stand up and take a responsible tilt at the future. She got none of these, in fact Tait celebrated his gold with other women, lots of other women in an orgiastic sexual spree. When they were eventually divorced there was nothing to split. Nine years later on his death there was no will. There was no need. The more well-heeled of his friends paid for the funeral. One of them, Dave Norris, says that deep down Tait probably did want what everybody else had life but he just couldn’t face the commitment or the responsibilities. “He was well aware of his deficiencies and I think the booze was something to cover up says Norris “He was always the exaggerated life and soul of the party but under it all was a creeping loneliness. After the party was over, or after the bar where Taity was always the star, was closed people went home to their material houses in their material cars and Taity just went off to a lonely room somewhere or a club to drink with himself.”

By most people’s standards Robin Tai was a failure at everything except the rather obscure art of throwing the discus but for all that his range of friends was vast and among them are few who will say a bad word about him and many who were prepared to go on being emotional props through his increasingly frequent bad times. Runner John Walker’s most enduring memory of Tait goes back to 1972. “I was just a kid, 19, struggling to make the qualifying time for the Olympics. It was cold, windy, a shocking night at Mt Smart, you had to be mad to be out there. Twelve people turned up, most of them because they had to be there, my coach, my parents, a couple of time keepers and two spectators, one of whom was Robin. He was out there yelling, driving, motivating. I owe him for that.”

When Walker and Rod Dixon started the Athletic Attic chain of sports stores Tait would drop by the shop on a Friday night to talk and work. They never paid him but Walker got him free training and competition shoes for his size 14 feet. But as the years went by the task of nursemaiding Tait had the potential to be a full-time job. Greg Denhohn, onetime New Zealand junior discus champion, Auckland rugby representative and successful lawyer, got Tait as a flatmate after his second marriage break-up. They’d become friends around the bar at the Ponsonby Rugby Club and when Gay went Denhohn offered Tait a home in an old house in Parnell. Deohohn says of him: “He was different. He was prepared to forego anything for his sport. He chose athletics over everything. He often said ‘sport is my life and life is my sport’. I, on the other hand, felt I had to give up my sport. I had to make certain choices. No one was going to pay me to play rugby.”

Denholm probably got closer to Tait than any of his male friends. It was he who picked up Tait’s difficulty with the written word almost immediately, but it was never discussed. “In his own way he was intelligent. He was very involved with psychotherapy, in relation to the mind governing the body in achievement and performance. He was forever playing records and tapes on the powers of positive thinking. He used this a lot in his own performance, psyching himself, and also to good effect with the athletes he was helping to train and it got results.”

Tait’s oldest daughter, Karen, came to live in the house for a couple of months when she first moved to Auckland. She was 18 and hardly knew her father. They were at odds initially, he was scared and didn’t feel adequate to look after her, but they became closer before she moved on to build her own life in the city as a social worker. Karen Tait read these lines at her father’s funeral

I cried for me last night

I had lost something inside

My Journey began with confusion

And travelled through anger and sorrow

Until I reached my place of understanding.

Even in his last years the by-now gross Tait could still charm women. He talked to them rather than at them and he wasn’t a sexual threat. By now ‘his steroid-addled body wasn’t performing too well sexually so he got his kicks out of talking with women, touching them and massaging their bodies. He had two girlfriends at the time of his death. They gave him money and they wept at his funeral.

After two years with Denholm the Parnell house was sold and the bachelors went their own ways, Denholm to a nice house in Devonport, Tait to one of those skid row private hotels, where derelicts and life’s forgotten people go. Tait had never been good at holding a job and now, with jobs harder to get, and in the absence of a normal family or social life he spent most of his time hanging out in Clive Green’s gym where he worked as a sometime instructor and cleaner, in pubs all over town, at the Ponsonby Rugby Club training shed, where he acted as the team’s assistant baggage boy, and around the reception desk of Graeme Hayhow’s Khyber Pass Physiotherapy Clinic, a good place to be when your physical power is weakening and your mind is struggling too, a patch-up clinic with a constant flow of stars happy to talk about sport and listen to his funny stories.

Hayhow, a gentle man who’s probably got more sports people back competing than any other physiotherapist in the country, smiles when he talks about Tait. He has happy memories and a lot of sadness remembering the man who lay on his couch, often five days a week, for months on end. Both Hayhow and his partner Doug Edwards knew Tait was into drugs; the steroids he admitted taking and other things he wouldn’t talk about because he knew they didn’t approve. Here are two more intelligent, successful professional men who were prepared not only to nurse, completely free of charge, a man who was doing silly and dangerous things to his system, but also to help him to the point of teaching him massage techniques and setting a room aside so he could work as a masseur.

Why? Tait did nothing but drink their coffee, 10 spoonfuls in a cup and let them down. He was a gifted masseur but the room remained empty. Tait just never got around to applying himself. Hayhow can’t explain why he loved Tait. He says it’s probably got something to do with his enthusiasm, his application to sport and the fact that he said things no one else would say “He said to the sports establishment you are holding New Zealand back. He told officials what he thought, and he was right a lot of the time, no one else had the guts to say it. . “He never owned much, but if someone said they liked his t-shirt he would take it off and give it to them. And he was a great morale booster. I went away as physiotherapist with the Oceania team to the World Games in Rome in 1982. Robin was the life and the spirit of the team. He acted as assistant masseur, his room was open till all hours. He was a motivator, a maker of good vibes.

“We also saw the depressed strange non-understandable side of his character while he lay on the couch, the side that did and said awful things. We worried about him, but you couldn’t help that part of him. He was a Peter Pan personality, but he had so much good within him that you just ignored the bad bits.” Hayhow and Edwards always saw Tait when he was in pain. He would crawl in with a locked up back an injury caused by two damaged joints in the lower part of his spine and be out throwing again the next day. “He had a great ability to deal with pain on a day to day basis and he had great recuperative powers. He probably put his body to more strain over the years than any other athlete, and he did a lot of that with positive mental attitude” says Edwards.

He produces a tatty piece of paper from his bookshelf. It’s one of numerous pieces of paper Tait would cut from magazines, little rhymes he would recite to anyone who would listen, along with his catch cry “when the going gets tough the tough get going”. What is printed on the scrap of paper is trite and largely forgettable but the last line makes a point Tait failed to appreciate: “A winner paces hirnself, a loser has only two speeds; hysterical and lethargic.”

No amount of positive thinking could remove the pain Tait was in the last day he crawled into the Edwards/Hayhow clinic. It was March 13, just three days after he lost his national discus title to Wellington’s Henry Smith. He was pale, shaking, and obviously very sick, in search of another quick patch up job. For the first time in months Tait had got a job. A good job with a car paying $18,000 a year as a salesman for a medical supplies company. They wanted him to make television ads. They also wanted him to start work the next day. Doug Edwards saw Tait. He was used to him being in pain but he knew this time it was more than a musculo-skeletal problem. He worked on him briefly but saw he was doing no good. He told him to go and see his doctor. He never saw him again.

Everything in the story of Robin Tait’s life and death leads to the need to talk to Dr Lloyd Drake, one of this country’s leading sports medicine authorities. Drake is known in the sport world as “Lloyd the Needle” because of the success he has had with injected cortisone treatment on top athletes. He was Tait’s doctor during his years in Auckland. He is a controversial figure who was investigated by the medical authorities a couple of years ago for talking to the press about his treatment of athletes. In the matter of Robin Tait, however, Dr Drake’s tongue became tied. He initially agreed to talk to me but a few days later on the morning of our meeting his nurse called to cancel the appointment. Said she: “Dr Drake doesn’t want to talk to you now or ever.”

Dr Drake was only one of many people who seemed disturbed that Metro was writing about Robin Tait. One of Tait’s latter day training and drinking mates, Greg Burgess the All Black prop and a man who drives a Rolls Royce initially assured me that he’d be happy to talk about Tait and then broke two appointments. When offered the chance to chat over lunch, the 18 stone Burgess said he didn’t eat lunch.

Next, New York marathon winner Rod Dixon came to me to say a ”some of the boys around town were a bit worried about some of the questions you are asking. Dixon suggested that it would be a good idea “to let sleeping dogs lie.” Another who wouldn’t talk was the woman probably closest to Tait until the time of his death, national shotput champion Glenda Hughes. She was Tait’s training partner, protégée and surrogate sister. As a policewoman Detective Constable Hughes was solid enough to stand up to and over Tait. Maybe he was scared of her. Someone asked her why she hadn’t stopped Tait from taking his lethal diet of pills and booze and her answer was “You can’t sew a grown man’s mouth up.”

Glenda Hughes’ dilemma is understandable. She knew the man and his failings and she tried, unsuccessfully to help him. Glenda Hughes organised the new job he never quite made and then his funeral, accepting condolences like a grieving widow. Tait had taken her from mediocrity to national champion in three years, but the journey had cost her emotionally.

The one person who would talk freely about Robin Tait may be the one to have the most to lose. Walter Gill, 32, is a former New Zealand discus champion. He won the title in 1975 when Tait didn’t compete because of injury. Gill left the sport in 1976 to build up his concrete construction business and to build a house for his wife and children. He came back two years ago, boosted by Tait’s enthusiasm and training help. Tait had keys to Clive Green’s gym and he, Gill and Hughes trained there after hours. Gill says he decided to talk about Tait because he had been warned not to. ‘I’m my own man and I don’t like being pushed around,” was his rationale. Gill says most people who want to be champions in strength sports have taken steroids. The most common anabolic steroid used in this country is Dianabol, either injected or taken in pill form. When they’re in full training throwers take two to four 5mgm tablets a day. They’re not readily available here but are sent in usually from Australia where they can be bought over the counter for $60 a hundred.

Of Tait, Walter Gill says: “I never felt sorry for him. I accepted him for what he was. Taity would tell me about technique and I would listen to his problems. He was declining. He was an alcoholic though he would never admit it and he was on the way out in sport. I thought he would die young, it was inevitable but not that soon, maybe in the next 10 years.”

Tait talked a lot to Gill about death, about hiring a bus to take him to the top of the harbour bridge for the big jump. He told Gill twice in the last year that he wanted him to have all his throwing equipment when he was dead. Straight after his defeat at the nationals, he went to remove his bag of throwing equipment from the boot of Gill’s car and then threw it back saying “I won’t be needing those anymore.” Gill thought it was just Tait exaggerating again, telling lies, more drama.

“But for all his faults I miss him badly. He’s left a great, gaping hole in my life,” he says sadly. As this issue of Metro was on the press a letter was received from Simpson Grierson, lawyers acting for Walter Gill. It alleged that I had “misunderstood” parts of my two interviews with Gill and demanded that reference to his “either buying or using drugs” be withdrawn.

Tait’s last few weeks were the most I pitiful of his sad up and down life. Home for his last five months was a dingy single room on the top floor of the Shakespeare Tavern on the comer of Wyndham and Albert Streets. He shared his last months with a musician, Garry Powell. Powell refused to take me upstairs to see Tait’s room. The management wouldn’t like it, he said. Instead we talked edgily in the public bar, the Stratford Bar, with its grubby beer-stained carpet, saggy green velvet chairs and the New Zealand rowing eight staring down from the walls. This is where Taity hit the deck.

He had lived at the Shakespeare since November and a bust up with Trish Butterworth a Social Welfare employee and the last of many good and loving women who propped him up emotionally and financially. Powell is edgy as a number of young women approach him. “My girls,” he calls them and hands them keys from his pocket. They disappear. He says the big man barely ate during the last weeks of his life, although he kept on swallowing raw eggs.

Powell, who was once a nursing student was the one who finally showed the pain stricken and yellowing Tait into a car bound for the Auckland Hospital accident and emergency department on the night of March 14. Tait had seen Lloyd Drake the previous day but Dr Drake had apparently seen no need to hospitalise his patient. Instead he sent him back to physiotherapist Graeme Hayhow with an Accident Compensation Commission form for more treatment on his back.

Powell and others at the Shakespeare had been telling Tait for weeks that he was sick and should slow up, but scared of the increasing pain, depressed at his failure, worried about the new job and fired by an alcohol-rich, food-free diet, he plunged on towards self-destruction. Powell handed Tait an orange juice on the stairs of the Shakespeare. As he clawed his way to the car, the big man begged for a scotch but no one would give him one.

That was the last Garry Powell saw of his friend. After finishing work that night he went up to A and E and waited five hours but was turned away. By now Tait was sedated to try and take the strain off his body. People considered more respectable than Powell, friends and family had taken over responsibility for his last hours. Over the next few days the hospital handled hundreds of calls inquiring about Tait’s condition and offering get well messages. Glenda Hughes and Tait’s sister Glenda Cutler drew up a list of five people who could visit the inert and unconscious athlete. The musician was not on the list and that hurt him a lot.

Six days later after failing to regain consciousness Robin Tait died following massive blood loss after surgery for removal of pancreas and duodenum. The post mortem stated that he died from acute pancreatitis, an inflammatory and often fatal condition of the pancreas which in some cases can be shown to be related to excessive alcohol intake. At a later inquest Dr Lloyd Drake gave written evidence that failure at his sport and an alcoholic binge had been factors in Tait’s death.

A few days later Greg Burgess trudged up the stairs at the Shakespeare to clear out his dead mate’s room. It was littered with pill bottles and not much else. There was no sign of the gold medal. It had been thrown onto the Whitford tip in a fit of rage and depression when Gay Tait left back in 1975.

–