Apr 8, 2014 Sport

Steve Williams, one of the most successful golf caddies in history, knows the value of speaking his mind.

During the final round of the 2006 British Open, rules official John Paramor approached final pairing Tiger Woods and Sergio Garcia and told them they were “on the clock” — a golfing term meaning hurry the fuck up.

Woods was at the absolute top of his game — bigger than the game — rooting around with all and sundry, untouchable. Rules are rules, but still it took some pretty big balls to tell Tiger he was on the clock when he was closing in on one of the biggest titles in golf. But if you were going to tell him, Woods wasn’t even your main concern.

“I’ll fix it,” Steve Williams said, and Tiger walked off, knowing that was the truth.

“Fuck, John!” Williams reportedly said to Paramor, a man generally considered one of the fairest in the business and just doing his job, “This is a fuckin’ joke! There are cameras going everywhere. It’s a fuckin’ disgrace. Don’t put my man on the fuckin’ clock!”

They caught up anyway, because rules are rules, but what did Woods know about it? Only that Stevie had it. Woods won the tournament by two shots.

For anyone who knows anything about Steve Williams, it’s not a surprising story. He has done things in defence of his players, particularly Woods, that are indefensible. Cameras are often involved. He has kicked cameras, thrown cameras in lakes. He has yelled at people.

“Steve could be a bully at times,” says Mike Clayton, a now-retired Australian professional. “He didn’t fool around. He didn’t mind making his presence felt that, ‘I’m the best caddy and my man is the best player and fuck off out of my road.’”

In 1984, Clayton was scheduled to play in a tournament in Biarritz, France, for which he didn’t have a caddy. He asked Williams, aged 20, to come and work for him.

Standing on the practice fairway the first day of the tournament while Clayton hit a few warm-up balls, Williams said: “I’ve watched you play a bit. It looks to me like you don’t concentrate particularly well. It’s because you’re not thinking about what you’re doing. No matter what happens this week, I just want you to pay attention, concentrate on every shot.”

Clayton won: the only time he would win in 311 tournaments on the European Tour over a 26-year career. He hired Williams for the rest of that season, offering him £200 a week — double what he says was the standard rate for caddies at the time.

“He was terrific,” Clayton says.

At the end of that year, Williams fired him.

Two hundred pounds: what a joke. Top caddies today routinely take home $US100,000 when their player wins a top-tier tournament. For Steve Williams, this happens a lot, but he’s not the only one. Last year, the caddy for top Swedish player Henrik Stenson bought himself a Ferrari, having earned, by some estimates, around $US2 million for the season.

Williams doesn’t remember £200. He remembers getting £50 a week and a percentage of players’ winnings through the early years of his career. He remembers making over £100 for the first time at the Tunisian Open in 1987: “It was like, ‘Wow! 100 pounds!’” he says. He spent it on a camel race.

Through his early years, Williams slept in hostels, sharing rooms with other caddies. They were people who had a reputation for drunkenness, irresponsibility and poor hygiene. That reputation no longer exists. $100,000 will get you bodywash.

During his time with Tiger Woods, Williams was often referred to as New Zealand’s highest-paid sportsperson, which is not a claim he disputes, but it clearly angers him that people might think he is in it for the money.

The first tournament he caddied at was the 1976 New Zealand Open. He was 13 and his dad had organised for him to carry the bag of Australian Peter Thomson, an Australian golfing champion who had won the British Open five times. Williams had been intrigued by caddying since the age of five or six and had caddied regularly for players at his local course at Paraparaumu, but when Thomson finished third at the New Zealand Open that week, Williams knew it was what he wanted to do with his life.

He was already playing golf off a two handicap — a standard that suggested a possible professional playing career. But he says that idea never entered his head. He doesn’t know why.

“I just wanted to be a golf caddy.”

He told an Australian professional that he was going to Europe to become a caddy and asked him if he had anybody to carry his bag. The guy said no. Steve Williams left school and flew to London, aged 15.

By the time he was 18, he was caddying for Greg Norman, the game’s emerging global superstar.

“Nothing has ever fazed me too much,” he says, “but when I got to London Airport having just flown out of Paraparaumu Airport, I realised that the world was a bit bigger than New Zealand. I remember thinking, ‘Oh, now hang on, you don’t just walk out of the airport and there is one road to get on. There are quite a few options here.’ I will always remember that.”

By the time he was 18, he was caddying for Greg Norman, the game’s emerging global superstar.

At Waikaraka Family Speedway on a warm Saturday evening in January this year, Steve Williams was racing in the New Zealand Super Saloon Championships. He is a former national champion, but this year he had a brand-new car, a four-bar car, which he was still learning to drive.

“It’s a big thing to do this late in my career,” Williams said.

“If you don’t try, you don’t succeed.”

The night before, in the heats, he had nearly flipped it. Race promoter Bruce Robertson says of the Super Saloons: “They’re going 80-90mph, doing a 15-second quarter mile on an oval. Most cars can’t do that in a straight line. They’re doing that on an oval. They’re right on the hairy limits.”

Williams was racing in a repechage that Saturday night. Only the best two finishers would go through to compete for the New Zealand title. He finished fifth. In the two subsequent consolation races, he finished seventh.

Tiger who? That man hasn’t won a major golf tournament since 2008. Steve Williams doesn’t work for losers.

People walked past Steve Williams’ car in the pits, with its Caddyshack Racing logos, and pointed. Sometimes they made woeful little imitation swings of the type that would disgust him were he holding their golf bag. One father bent to his son and pointed: “Tiger Woods’ caddy.”

Tiger who? No, no. That man hasn’t won a major golf tournament since 2008. Steve Williams doesn’t work for losers. He works for Adam Scott, reigning champion at the Masters, the world’s most prestigious golf tournament.

Top New Zealand caddy Anthony Knight says, “I remember someone saying — I don’t know if this is exactly true or not — when Stevie was caddying for Tiger, Adam Scott was on the putting green, in the Masters I think it was, and I got told that Steve went up to Adam Scott and said, ‘Listen mate, what are you doing mate? You should be winning one of these. Pull your bloody finger out, mate. You’re a bloody great player. It’s sad to watch you not reach your potential.’

“I’m not sure if that’s true or not, but that’s the sort of thing Steve would do. He was mates with Adam Scott beforehand and you could believe he’s frustrated that he hasn’t done what

he wanted him to do. That’s the kind of guy he is.”

“It wasn’t exactly as Anthony put it,” Williams says, when I ask him about it. “How it actually went, the year was 2010 I believe, the year that Adam finished second to Charl Schwartzel.

I believe it was 2010.” (It was 2011.)

“On the Sunday, he was on the putting green on his own. And I was standing over on the range just waiting for Tiger also on my own and Adam’s caddy wasn’t there, and I went up to him and said to him just basically in a nutshell, ‘Today’s your day, you’ve got to say to yourself the whole 18 holes that you are the best player out here. You’ve got to win this tournament no matter what and don’t let anything affect you. If you hit a bad shot, just don’t let it bother you. Just say, I am Adam Scott — I’m the best player in the field today, I’m going to win this tournament.’

“That’s what I said to him. Of course he played brilliant and that was his best-ever finish. Charl Schwartzel birdied three of the last four to beat him. Phenomenal finish, but that was his best-ever finish in a major up until that point so… I guess Adam had never heard something so sharp and direct, the way I said it.

“I think that’s what sort of led to me ending up caddying for him.”

Tiger Woods fired Steve Williams on July 3, 2011. Nobody knows why for sure. Woods said in a statement that it was time for a change. He had been injured for a couple of months and in the meantime Williams had caddied in a couple of tournaments for Scott.

According to Williams, Woods made a phone call saying they needed to take a break and that was it.

“There is no denying that I was incredibly disappointed in the way that Tiger handled the end of our relationship,” he says now, having said worse at the time. “He didn’t handle it right.”

A month later, Scott and Williams won The Bridgestone Invitational, part of The World Golf Championships. Woods, in his first tournament back from injury, finished miles back.

As he walked up the last hole with Scott, the crowd started chanting Steve Williams’ name. Reporters wanted to talk to him. He was interviewed live on television. If that ever happened to a caddy before, nobody remembers it.

“I’ve caddied for 33 years, 145 wins now, and that’s the best win I’ve ever had,” Williams told television reporter David Feherty.

It was an outrageous comment. He had won 13 major tournaments with Woods, including the 2006 British Open, when Woods had sobbed in his arms at the sinking of the final putt, which came two months after the death of his father.

Williams became the story. There was comparatively little attention paid to Adam Scott, who had just won a World Golf Championship event.

“I have never experienced anything like that,” Williams says now. “The people were chanting my name. It was a unique experience and my head was filled with emotion.

“He came up and put a microphone in front of my face. I was in a different world. I regret what I said. I’ve done some things along the way that people have taken offence to, but that is the only thing that I regret.”

At a caddies’ awards party later that year, he said: “It was my aim to shove it up that black arsehole.”

“We live in a country that’s a multiracial society. We owe a lot of our history and tradition and culture to a lot of the Polynesian communities. I don’t know how you can say anyone from New Zealand is racist.”

That also got worldwide attention. He took to his website: “I now realise how my comments could be construed as racist. However I assure you that was not my intent. I sincerely apologise to Tiger and anyone else I have offended.”

Later, he told Murray Deaker on Newstalk ZB that others had said worse things that night and that it was blown out of proportion.

“You make one comment like that — in a room, having a bit of fun — and how does that make you a racist?

“We live in a country that’s a multiracial society. We owe a lot of our history and tradition and culture to a lot of the Polynesian communities. I don’t know how you can say anyone from New Zealand is racist.”

It didn’t seem to bother Adam Scott much. In a statement, he said he does not condone racism and accepted Williams’ apology, “knowing that he meant no racial slur”.

Correlation and causation are difficult to separate, but since Williams became his caddy, Scott has become arguably the best player in the world.

“That is a hard question to answer,” Williams says, when asked about his impact on the players he caddies for. “You have to ask the players that, but if I took, say, the example of Adam, he has gone from being a very ordinary performer in the majors and now I have caddied for him for two years, and he has had the best record for the last two years in the majors. He had the lowest stroke average, the lowest aggregate total in 2012 and the lowest aggregate total in 2013 and he’s had the most top tens.”

There is some debate over whether Steve Williams is the best caddy in the world.

Michael Waite, who caddied for Michael Campbell during his best years and also some of his worst, believes Peter Coleman would be the next biggest-winning caddy and he has less than half the number of Williams’ wins. Caddying legend Bones Mackay, who works for Phil Mickelson, has around 50. “There would be a few guys in the 40s,” Waite says, “but Steve’s in the 100s. No one’s even close to his level of success.”

“Steve was everything. He was the ultimate. Nobody does it all as good as Steve.”

The counter-argument is that he has all those wins because he has caddied for three of the all-time great players, including one who — had he been more circumspect with his penis and had better luck with injuries — could have been the greatest of all time. To which the counter-counter argument is that those players chose him for a reason, and he spent years with all of them: more than a decade each with Woods and four-time major winner Raymond Floyd, and seven years with Greg Norman.

“Without question, Steve is the best caddy in all arenas,” Floyd, now 71, says.

“Steve was everything. He was the ultimate. There might be an individual caddy that may do one thing better, or another thing, but there is nobody that does it all as good as Steve.”

Fanny Sunesson is the caddy Williams most admires:

“I decided very early during my first year, that I was just always going to say what I believed,” Sunesson says of her style, “because otherwise I might as well not be there.”

She made her name as the caddy for Nick Faldo when he was the world’s best player, then caddied for Henrik Stenson before retiring in 2012 after tripping over a fairway rope. She is considered one of the greatest caddies of all time.

“If I was a player and I needed a caddy, Steve would be my number one choice,” she says. “It is a lot of things but definitely one of them is that he is not afraid of saying what he thinks and I think that’s good. It is good for the players.

“He has an ability to get the best out of his players — that is another key — and that involves a lot of things that you can’t give a recipe for.”

When Adam Scott became the first Australian to win the Masters last year, Australia went crazy for him. Peter Thomson never won the Masters; neither did Greg Norman. There were endless mawkish tweets of adulation from former Aussie players: “Waltzing Matilda … Waltzing Matilda… you’ll go a waltzing Matilda with me…..#adamscott”, wrote Steve Elkington.

After four rounds, Scott had been tied with Angel Cabrera. They went to a sudden-death playoff. On the second hole, Scott asked Williams to read the putt, which is to say, asked him which way it was going to break. It was something he didn’t often ask, but it was late, nearly dark, there was extraordinary pressure, and Steve Williams had caddied in the Masters every year since 1987, more consecutive tournaments at the Augusta National course than anyone else in history. He had looked at that green over and over and over. Scott thought it would move right to left, about the width of one hole. Not even close, Williams told him. It’s at least two holes’ width.

Of course, that’s all fine now because he was right and got to throw one of his trademark tournament-winning high fives at Scott, but isn’t it interesting to think that top golfers expect to get critically valuable advice from the guy they employ to carry their bag, clean their clubs and pick up balls?

Isn’t it also interesting to think that Steve Williams was prepared to stand there and tell his friend, a far better golfer than he, who has read and sunk so many difficult putts without turning to ask his thoughts, and who has a chance of becoming the only person from his country — a proud and arrogant sporting nation — to win the world’s biggest golf tournament, that he was wrong?

How much is on the line there? A lot. Oh yes — a very great deal indeed.

Maybe most interesting is the thought that Steve Williams, famed loudmouth, hadn’t offered his unbidden opinion on every putt in Adam Scott’s career.

At the end of last year, Williams and Scott went to Australia to play four tournaments in four weeks: the most important tournaments in Australia but meaningless on the world stage, especially to a player who had just won the Masters.

It was a triumphant homecoming. To each tournament, Scott took the green jacket, the strange prize given each year to the winner of the Masters, and he had his photo taken with fans and signed autographs: so many fans; so many autographs.

“I think the reception he got at the first one blew him away,” Williams says. “It was amazing, the atmosphere at the first tournament. People were just so excited that he had won the green jacket.

“He wanted to put on a good show and not just go down there and play in the tournaments. He really wanted to put up a good effort and of course when he won the first one, I think that really set the wheels in motion.”

The following week, he won the Australian Masters. He then played in the World Cup of Golf, which he and Jason Day won for Australia.

The final tournament was the Australian Open. He dominated almost from the start and led through the first three rounds. All that was left was to wrap it up on Sunday.

The day dawned fine and clear, etc, etc. It came down to the last hole. It came down to the last shot to the green on the last hole. Scott was one shot ahead, but his main competitor, Rory McIlroy — 24 years old, two-time major winner, best young player in the world, widely considered the next Tiger Woods — hit an almost perfect shot to the final green. The ball stopped just 10 feet from the hole, daring Scott to make a mistake.

For the average golfer, the game is made up mostly of technical problems: an inability to get the ball to go where you want it, to hit it cleanly the distance you intended, with the right amount of spin and movement. At the level Scott and McIlroy play, technical issues don’t decide tournaments — they can all hit the ball properly — but pressure does.

On that last hole, Scott could have chosen to hit it straight at the pin and try to out-gun McIlroy, whose short putt was for birdie. He had been playing such incredible golf, nobody would have been surprised if he hit it even closer. His best alternative was to hit a safe shot left of the hole, where there was a sort of backstop, giving him some margin for error.

In such moments, caddies can make their name. Steve Williams has shown that, again and again over the previous 35 years.

In 1999, at the US PGA Championship, Tiger Woods had still won only one major, and that was two years earlier. He was the biggest story in golf and everybody knew he was supposed to be a superstar, but after those two years without a major there were questions.

His relationship with Williams was just a few months old; they weren’t yet close pals.

In the space of six holes on the last day, Woods had lost a massive five-shot lead. On the 17th, he played two terrible shots, and was left with a difficult putt to stay in the lead. It was pressure of a sort most of us will never know.

What if Williams was wrong and Tiger hadn’t won that tournament? What would have happened to Steve Williams then? We will never know.

The putt was obviously left-to-right, but Tiger thought he should aim just outside the hole. Williams said: “Nah, this putt, you hit inside the hole. I’m sure on that.”

What if Williams was wrong and Tiger hadn’t won that tournament? What would have happened to Steve Williams then? We will never know.

“From that point on,” Williams says, “we just went on an incredible tear and I think that was the bond that formed when a player asks you something under the incredible heat of the moment and you don’t hesitate — you go against what he says.”

In 2008, at the US Open at Torrey Pines, Woods had a broken leg and shouldn’t have even been walking. But there he was, standing in the rough on the last hole of one of the world’s biggest tournaments, trying to force a playoff with Rocco Mediate.

Tiger wanted to hit a regular sand wedge. Williams promised him he had to hit a lob wedge. It was 108 yards out, and they both knew that Tiger didn’t hit a lob wedge that far, but still Williams insisted.

All caddies will tell you that players hit the ball further late in important tournaments with pressure on and adrenaline in play. They’ll club a player differently then: give them a seven iron instead of a six. But this was different.

Williams says Woods told him, “‘Stevie, there is no way I can hit that club this far.’ I said, ‘Just trust me, you are coming out of the wet kikuyu grass, da da da da, you can get it there.’”

It was an incredible thing to say for many reasons, but the biggest is that, if the greatest player in the world thinks he can’t hit a club far enough, there’s a good chance he’s right.

“This is where the psychology part of it comes in. When you know the guy’s doubting you — there is an old saying you are better off to hit a good shot with the wrong club than a bad shot with the right club — and in that case, if you sense that the guy is sensing there is some doubt there, that is when you have got to get him off it, or talk him through it again, because when there is doubt, that is when a poor swing can come in.”

Tiger hit the lob wedge to the green, sank the putt and won the resulting playoff.

“It’s like, shit if you screw up, it’s going to cost your man the US Open,” Mike Clayton says of that moment. “And it didn’t seem like the right club. If you looked at the yardage, it was like no way that’s the right club. But it was.”

“I have always trusted my judgment,” Williams says. “It’s a feel thing.”

All jobs are mostly mundane; even the ones that look really glamorous. Steve Williams spends far more of his time doing nothing special than he does telling a broken-legged Tiger Woods to hit an impossible lob wedge from the rough on the last hole of the US Open.

With Woods, he would run through practice drills holding the shaft of a club against the side of Woods’ head — to help him keep it still — while Woods spanked balls down a practice fairway. With Adam Scott, he will circle the hole on the practice green, picking ball after ball from the hole as Scott machine guns them in from six feet.

He counts clubs before a round, keeps clubs and balls clean and dry, and he makes sure the clubs don’t make too much noise in the bag when he walks.

Before tournaments, he can be seen walking the length of every golf hole with a measuring wheel, writing down the distance from every conceivable point his player could hit a shot to every other point his player could conceivably hit a shot, making notes about bunkers, trees, troublesome lies and anything else that might affect his man.

This is what’s known as “drawing a book” and top caddies will do it in about five hours — sometimes more than 10 for a difficult course, if they’re doing it from scratch. In his heyday, Williams would do it in 90 minutes. He would run.

One of Australia’s best caddies is called Squirrel. For 13 years, Squirrel caddied for Geoff Ogilvy, during which time Ogilvy became one of the top players in the world. Together with Squirrel, he won the 2006 US Open — the last time an Australian won a major before Adam Scott’s win at the 2013 Masters.

Ogivly sacked Squirrel in 2012. Ogilvy’s ranking had dropped and he was looking to refocus his life in the same way he believed Adam Scott had refocused his: setting his whole life up to achieve his goals. Squirrel went to work for the middlingly successful KJ Choi. In March this year, Ogilvy was ranked 151 in the world and Choi was 89.

Such is the life of the caddy. “He’s a tremendous caddy,” Mike Clayton says of Squirrel, “and I saw him at the World Cup and he still beats himself up — every bogey his player makes is his fault: ‘That’s the wrong club; I’m a hopeless caddy.’ It’s like, ‘Squirrel, shut up, you’re a great caddy. I know how good you are. You’re great.”

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

While leading by heaps in the final round of the 2012 British Open, with Steve Williams on his bag, Adam Scott had spectacularly fallen apart, bogeying the last four holes and losing in a way that looked a lot like total mental meltdown.

But speaking to the media after the first round of the Australian Open a year and a half later, where Scott had just broken the course record, scoring 62, Steve Williams told the Australian media he saw the British Open disaster as a positive.

“I think it said to him, ‘You know what, I can actually do this, I really can.’ He’s knuckled down since then. He turned what could be a negative into a positive. You don’t get to where these guys are without hard work, and I think Adam’s pushed a little bit harder.”

Three days later, Scott was lining up that last shot to the last green to try to win his fourth title in four weeks. It shouldn’t have come down to that shot. All day, he had played great golf from tee to green but hadn’t been able to hole a putt. On the 17th, a hole where it had been incredibly difficult to hit the ball close to the pin, he did just that, then missed the putt. Williams had watched the same thing happen, over and over.

So there he was, hitting to the 18th green, needing, at least, to hit a safe shot so Rory McIlroy wouldn’t overtake him.

He aimed it 15 feet left of the hole, at the backstop.

“It would have been perfect,” Williams says. “It would have landed exactly pin high and taken one bounce and then rolled back to pin high. So it was spot on for distance — it just wasn’t the right line. He pushed it quite a bit right of where he was trying to hit that ball.”

It ended up over the back of the green in kikuyu grass. Arriving at the ball, Williams calculated his chances of winning from there at about five per cent. Scott hit it past the hole, missed the putt and lost by one shot.

“When you’ve had a great year you’ve got to remember the pluses,” Williams says. “To be fair, he had a lot of opportunities to win last year and he took just about all of them. He won five events last year. That is a spectacular year. So one little thing like that: when you are caddying for a player who has played as long as he has, and you’re someone who has caddied as long as I have, there is no disappointment at all.

“It’s disappointing in the moment but that is the last tournament of the year, the year is over and you start focusing on the next year. There is no major disappointment in that.”

Williams has told Scott that this year will be his last as a full-time caddy. Driving back from the Masters triumph last year, he realised it was time.

“I have had an incredible stint… It’s just time to go and do something else and spend more time with my family.”

“It was the oddest thing. You would think, it was an incredible week, to win the Masters — the first Australian — was a big story, and at the end of the week it was one of the first times I actually wasn’t that excited. I was like, ‘You know, that’s me. I’m done.’”

He still loves the job, he says, but it’s hard physical work, a lot of travel, and you can only do it so long.

“I don’t want to look back and think that the only thing I’ve ever done is just caddied. I have had an incredible stint… It’s just time to go and do something else and spend more time with my family.”

“Show up, keep up and shut up: The shut-up part — Steve didn’t say anything unless you asked him,” says Raymond Floyd.

“When I was in my zone and playing really well, I knew what I wanted to do. I didn’t need a caddy. I didn’t need his input. I’d ask him for the yardage; he would give me the yardage. But he was prepared if I said, ‘What do you think?’ I might throw that on him, but I might not do it every shot. And if I didn’t say, ‘What do you think?’ he wouldn’t say anything.”

Steve Williams has something to say.

“In 1990, when Raymond was attempting to become the oldest player to win the Masters,” he told Brian Wacker of pgatour.com at the end of last year, “he had a one-shot lead with two holes to go. He drove it right down the middle on 17 — the green was a different shape then: the pin was in the front right and the green still had a ridge to the left, so if you missed you always missed to the right because it was a simple up-and-down.

“He told me he was going to aim a little left of the hole and work it back toward the flag. The first thing that went through my head was, ‘What if you pull it left?’ I wanted to tell him to fire straight at it, but he was in complete control of what he was doing. And I didn’t say it. I always say what I think. It was the one time I didn’t. I’ve always regretted that.”

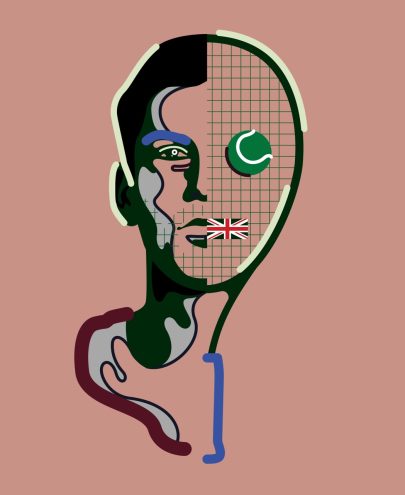

Portrait and speedway photos: Stephen Langdon.