May 12, 2014 Sport

How did Coliseum – a couple of guys with no experience in television – steal the rights to English football from Sky? And how will their deal change everything about the way we watch sport?

First published September 2013. Photos: Adrian Malloch.

The boardroom at Cooper and Company, in a handsome 19th-century building on Quay St, is a pretty pleasant place to spend time. There are huge artworks by John Pule and Peter Robinson, surfaces of stained hardwood and brushed stainless steel, with Britomart’s central square splayed out attractively along the entirety of two sides. It is, naturally enough, air-conditioned, and kept to a comfortable 21 degrees year-round. All the same, Tim Martin, the CEO of Coliseum Sports Media, was dripping with sweat.

“When I get nervous, I sweat,” he says. “Particularly out of my armpits. I get sweaty armpits and sweaty shins.”

“He’s got a plumbing issue,” his business partner Simon Chesterman says helpfully.

Martin was right to be nervous. It was a Friday afternoon in mid-February of last year, and at one end of the enormous boardroom table sat Matthew Cockram, the New Zealand CEO of Cooper and Co. Opposite was Peter Cooper, for whom the company is named, a man the National Business Review says is worth $650 million.

Earlier in the week, Martin had pitched his business plan to the pair. He wanted to sell people sports over the internet. To do so, he needed cash, and lots of it, to buy sports rights. Cooper and Co don’t just overlook Britomart, they own it — along with a wealthy slice of Dallas, Texas, and a number of businesses. Cash is not a problem for them.

If they liked his idea, Martin was away. But Cooper and Co were his best, maybe his only shot — people with the capital, resources and vision to support a battle which would in short order bring Coliseum up against Sky TV, an entrenched $2 billion company with 850,000 customers and a 20-year head start. The odds were firmly against Martin. Cockram estimates that of every 100 pitches they hear, they partner with one.

Every answer elicited mysterious laughter. Martin had no idea how his responses were being received. And all the while the sweat flowed.

They had called him in at short notice to ask a series of pointed questions about the nature of his plans. For the next two hours it was, Martin says, like a presidential debate, but with two moderators and one candidate. Every question consisted of three or more discrete clauses. Every answer elicited mysterious laughter, followed by the Coopers pair looking pointedly at the ground for many seconds. Martin had no idea how his responses were being received. And all the while the sweat flowed.

“By the end of it, I’d not only blown out my shirt,” he says, “I’d blown out my suit.”

Whatever he said, it worked. They met again, and again, and again in the weeks to come, and Martin’s drycleaning bills decreased accordingly. After six months, in September of 2012, Cooper and Co and Coliseum entered into a 50-50 limited partnership. Even then, the idea seemed too crazy to speak aloud. If all went according to plan, they would take away a key sports league from one of the 10 biggest companies on the New Zealand stock exchange.

Sky’s biggest shareholder at the time was Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, and they had deep pockets courtesy of annual profits of $120 million. The general perception was that the only real threat to Sky’s monopolistic domination of the pay-TV market was an ongoing Commerce Commission inquiry. Who on earth, in their right mind, would pick a fight with them?

Perhaps it helped Coliseum’s bravado that they had no experience in television. Martin and Chesterman, the company’s CEO and chief creative officer respectively, have deep roots in advertising and complement each other in business. Chesterman is digitally adept, Martin a near-technophobe. Chesterman is a former designer and advertising creative, Martin a former suit — an account executive.

The bearded Chesterman wears skinny jeans and 90s sportswear, and always a cap or beanie, while the shaven-headed Martin inclines to a suit with an open-necked shirt and Chelsea boots. Chesterman shrinks from the spotlight, Martin seeks it out.

They’ve got a lot in common, too. Each has a business failure in his past, a handy thing for an entrepreneur, and they’re both a little cynical about their former industry. Their senses of humour are near identical, and involve frequent and brutal self-deprecation. And, helpfully, they’re both obsessed with sport.

Chesterman, the son of an ad man and a staffer at the Auckland Art Gallery, went to Rosmini College, a North Shore Catholic school. He was, he says, “a bit unruly”. He drifted through his twenties, slowly accumulating an art history and philosophy conjoint degree while working at various galleries, and as a very unsuccessful male model. The interest in art remains — his own Karangahape Rd office overlooking Myers Park is lined with contemporary works by the likes of Andrew Barber, Nick Austin and Layla Rudneva-Mackay.

He taught himself design on a PC running Windows 95. One disastrous business fell apart when an anxiety problem rendered him “practically a shut-in”. A relationship with actress and Lotto presenter Sonia Gray, whom he would eventually marry, helped to revive him. His second business was more successful, and he developed a strong reputation as a designer and creative, working on the 42 Below campaign and later the launch of Yahoo! Xtra. That brought him into contact with Martin. The pair fast became friends.

Martin was also born in Auckland, but raised in South-east Asia, where his father worked to bring the wonder of Coca-Cola to a thirsty continent. He spent time in Manila, Hong Kong and Jakarta, whose expat communities gifted him his slightly plummy accent. “There were lots of guns,” he remembers. “Extreme, unbelievable wealth, living alongside people with no running water. It was lots of fun, though.”

Back home, he too drifted, spending a few years working at a BP service station in St Heliers, before completing a diploma in advertising at what was then the Auckland Institute of Technology (now AUT). He parlayed that into a job making coffee at McCann Erickson in Singapore.

Martin was one of four white faces — the other three were running the show. Unsurprisingly, he was swiftly promoted. Back home, he worked at Saatchis, before heading to London and a job at acclaimed agency Leagas Delaney. There he guided adidas through their football campaigns alongside global megastars such as David Beckham and Zinedine Zidane. He loved it.

“I liked sport,” he says. “But I really liked it as a business.”

In 2003, he came home again, married his partner Kate and returned to Saatchis — where he experienced something like an existential crisis about advertising.

“I was no good at it any more,” he says. “I didn’t think it mattered. I didn’t think what we were doing made any difference to anything. I’d sit in these meetings, and we’d argue over ‘should it be red, should it be blue?’ Who gives a fuck?”

Martin instead went into business with a friend to launch Good, a company that made bottled water. It failed. “It’s pretty hard,” he says. “To spend years on something, never really get it going, then meekly pull the plug. You feel like a fucking tit.”

He returned, disconsolately, to advertising. Kate saw the depression it induced, and told him to “get off your arse and figure out this sports business”. So he did.

Despite her lack of interest in sport, she had great instincts in strategy and customer experience, and her husband wanted her involved. They recruited Chesterman, and the trio founded Coliseum Sports Marketing in 2009 on the premise that “digital technology will fundamentally change the business of sport”.

It was the right idea, right time — but was it the right place?

The early years weren’t promising. They met with the heads of all New Zealand’s larger sports bodies, but the work they got was small beer: a campaign for NZ Cricket’s HRV Cup, some branding for the Breakers, social media for the Rugby Union’s ITM Cup. (Disclosure: I met the Martins through some copywriting I did for Coliseum on the ITM Cup, and see Chesterman socially. I also write for Sky Sport: The Magazine).

If that doesn’t sound like a lot of work for three years, it wasn’t. Chesterman and Tim Martin spent a lot of time gambling on sports — “constantly, frequently… not heavily”. To make the bets more interesting — and because it’s fun — they also watched a lot of sport. Particularly out of the US. The timezones mean their night games frequently play through the afternoons of a given work day. Perfect if you haven’t much on.

They subscribed to innovative new services from America’s National Football League, Major League Baseball and National Basketball Association that allowed you to stream any game you chose to a PC or TV via the internet. One afternoon, watching some American football in their offices on Beresford Square off K’ Rd, they had a revelation.

“What we realised was, when we were buying the NFL, we were buying direct from the NFL,” says Martin. “We weren’t paying Sky. We weren’t paying NBC. We weren’t paying anyone else. And we were getting this amazing quality stream that we could hook up to our projector, and project at giant size on our wall. It was incredible. We just thought it was such an amazing way to watch sport.”

What they had stumbled upon was vertical integration. This had been happening all over the internet for years — it’s tough to think of a consumer commodity that hasn’t cut out the middleman and gone direct to market. Clothes, music, wine, movies — if you watch it, put it in you, or on you, chances are the smartest brands will give you the option of getting it from them direct online.

It’s obvious why — for a little more work and administration, you get a whole lot more profit margin. As bandwidth capacity increased exponentially through the 2000s, switched-on leagues started to sell their matches online. Now, along with the big four US pro sports, you can buy and watch everything from the Professional Bowling Association to Major League Fishing direct from the bodies themselves.

For Martin and Chesterman, it felt like they had seen the future. They would act as intermediaries to help New Zealand sport do the same, supplying the technology and marketing while sharing the associated revenue. Local sports organisations, perpetually teetering on the margins of solvency, could be in charge of their own destiny. The money for grassroots sport and professional athletes alike would be increased. And they might be able to create a sustainable business helping organisations move into this world — engaging with the technology and marketing it to consumers.

They took the idea to the New Zealand Rugby Union, which was enthusiastic in principle but wedded to Sky, at least in the medium term. The rest of the New Zealand sporting community was not nearly so accommodating.

Most patronising of all was David White, CEO of NZ Cricket. He spent the majority of their meeting poking holes in their proposal, and within a month or so had signed a watertight eight-year deal with Pitch International, for the international rights to distribute Black Caps matches across television, radio, mobile and online (NZC also signed a separate two-year contract for the domestic rights with Sky)*. While the contract was trumpeted by the media — including myself in this magazine — as having made cricket safe for years to come, Martin and Chesterman shake their heads at that deal more than any other.

“How far is this tech going to be in eight years? It’s going to be incredible. What you want to be able to do is take advantage of it.”

The fact they have a vested interest doesn’t disqualify their argument. “Eight years ago there was no i-,” says Martin. “No iPhone, no iPad. That’s revolutionised everything. There was no Cloud. How far is this tech going to be in eight years? It’s going to be incredible. What you want to be able to do is take advantage of it,” he says. “But the bottom line is, if you’ve sold the rights, you’re out of the game.”

Matthew Cockram from Cooper and Co says most local sports bodies remain trapped in an amateur-era mindset. “They have these models where they’re used to getting a lick of money at the beginning of the year from one or two sources, and making that work. As opposed to getting much more involved in the business of getting to the customer.”

That’s where Coliseum was supposed to come in. Unfortunately, doors kept slamming shut.

Martin decided they needed to look elsewhere for proof of concept. If they could sell the right overseas-based league to the New Zealand sporting public, perhaps the local sports bodies would come around. Football’s English Premier League (EPL) was the obvious choice. It’s the biggest league for the most popular sport in the world, and football is also, as Martin knew, the biggest participation sport in New Zealand.

It was clearly the best example they would find. The New Zealand EPL rights had been sold in November of last year, part of the $NZ8 billion-$10 billion winning bid for the competition. But MP & Silva, which bought the rights for much of the Asia-Pacific region, are a rights clearinghouse; they don’t sell to consumers. Subject to some (arduous) conditions, anyone can buy sports from them. The rights were available, and not being pursued — “they were just sitting there,” says Martin.

Flush with Cooper and Co cash, Coliseum entered negotiations. And won.

The significance of this victory can’t be overstated. Sky was founded in 1987 by Trevor Farmer, Alan Gibbs, Craig Heatley and former New Zealand opening batsman Terry Jarvis. All four are fixtures on NBR’s rich list, and the company they founded went on to dominate the sporting landscape. The satellite service went to air in 1990 with the Winfield Cup — the precursor to today’s National Rugby League — and ESPN. Soon after, Sky screened New Zealand’s cricket tour of England, and in 1993, it started to pick up National Provincial Championship rugby games. Other sports followed at a gathering pace, with the All Blacks the tipping point, creating the six-channel TV-sport monster we know today.

Sky has occasionally lost or shared big competitions before (the Olympics in 2008, sometimes Wimbledon, the 2011 Rugby World Cup), but tellingly they tend to be one-off sporting events. Sky’s business relies on vast numbers of subscribers remaining hooked all year round. And while it puts serious effort into its other offerings, from high-brow (SoHo) to trashy (E!), everyone knows the big prize in pay TV is sports.

It’s what people are most prepared to pay to watch, and because it has little value unless it’s live, sport — unlike, say, movies — is not attractive to pirates.

For evidence of just how important exclusive sports rights are to Sky, look across the Tasman. Foxtel is Australia’s main pay-TV network, but despite a market five times as large as New Zealand’s, it has only around two and a half times the subscriber numbers — 2.27 million to Sky’s 850,000. Foxtel is present in only 35 per cent of homes, while around half of all Kiwi households have a Sky box.

This is largely because Australia has anti-siphoning laws which give free-to-air channels the right to bid first for sports: the big games in the big sports are routinely screened live and free.

In New Zealand, the Commerce Commission is currently completing a long-running inquiry into the legality of the broadcaster’s deals with internet service providers. But Sky continues to laugh off the monopoly argument while accumulating ever more of the world’s most popular sports competitions.

The loss of English football represented its first major setback. Sky was suckerpunched by an outfit it didn’t even know existed. It needed to fight back, and fast.

Coliseum, meanwhile, having delivered the punch, now had to move just as fast. It had to build an entire infrastructure to deliver the service — and convince the public to buy in.

At the time, Coliseum had just three employees — Chesterman and the Martins. Suddenly, they were working like dogs. Kate focused on strategy and customer experience, while her husband spent half his time on planes and in hotel rooms. He flew to New York, London, Singapore multiple times, meeting representatives from the EPL, MP & Silva and NeuLion, a US online video technology company. Chesterman was hunkered down sweating the technology, and the look and feel.

All tasks seemed thankless at times. In mid-May, I Skyped with Martin. It was 6am in London. He was slightly hungover, and had lost his phone — something he had also done in Hong Kong and Singapore. Still, he was at the luxury May Fair Hotel, where the EPL had flown him and the other rights holders for the launch of the next three years’ worth of coverage. It could be worse, right?

The catch was, he was there for only two nights. London is a long way to fly for two nights.

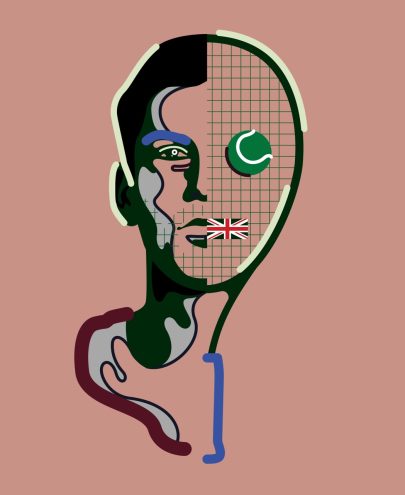

Chesterman was in his K’ Rd studio, working with long-time collaborator Simon Oosterdijk on the graphics and appearance for Premier League Pass. They were looking for a flavour of the sports posters they had on their bedroom walls growing up, and tossing up between futuristic or classic football as a foundation.

On Oosterdijk’s screen, Liverpool captain Steven Gerrard was rendered in five frames and five different colours, whirling balletically through an airborne strike. Chesterman was alive with the possibilities. “We can kind of create our own world,” he said. Later he added, offhandedly, “One thing we’re not sure about is what we’re allowed to do.”

A month later, now ensconced at Coliseum’s new offices within Cooper and Co, he sent the marketing material to the EPL for approval. To me, only half-jokingly, he called it “a virtuoso performance… in abstraction and erosion”, encompassing “the impermanence of life and sport”.

The reply came overnight. “Everything … was the exact opposite of what was in the Barclays EPL brand guidelines,” he said, sounding utterly defeated. “It was so heartbreaking.”

The brand guidelines had been issued only after the season launch, and Coliseum made the rookie mistake of thinking that if they made it pretty enough, the concept would fly. Unfortunately, when you’re dealing with the biggest sports league in the world, that’s not the way it works.

Chesterman gets on with the rest of the work. They’re incorporating cutting-edge technology to make the customer experience more personalised, and seamlessly integrating social networks. Only time will tell if this is something viewers want with their football, or just dead spin that gets in the way.

On the morning of June 17, the Martins and Chesterman gathered for their regular Monday work-in-progress meeting. Martin is bouncing off the walls: he has the final 54-page contract for the EPL — all that remains is a signature from Beatrice Lee, the regional head of MP & Silva in Singapore. He calls in a secretary from Cooper and Co for the job. “Get this on the fastest courier known to man,” he implores her, and then continues to drive the urgency home, over and over.

It’s completely unnecessary, if understandable: this is the document that will make the acquisition official. Still, a secretary at a firm like Coopers doesn’t need to be told twice about a project’s importance. There is a cultural tension that exists between Coliseum’s start-up energy and the quiet serenity of Cooper and Co. The latter have made their guests very welcome, but Coliseum aren’t used to having to book meeting rooms and Martin is forever having to shut the office door as his profanities escalate in intensity. He swears loudly, lustily and well. In his world you’re either a “great guy”, a “fuckwit” or a “fucking moron”. Their partners are “brilliant to work with” or “trying to fuck us”. Always delivered with a broad smile. A few weeks later, Coliseum will decamp and set up their own shop across the square. Martin can now swear to his heart’s content.

They don’t quite grasp just how the news business works and what big news it will be

Sports broadcaster Martin Devlin is a friend of Martin’s, and phoned over the weekend to say Sky has told key staff it has lost the EPL contract, and Kate reports she has heard Sky may be about to announce the fact publicly. “Why bother? Why would they do that?” says Chesterman. There’s a sweet naivety to this, a sense that they don’t quite grasp just how the news business works and what big news it will be. They decide Sky won’t tell until it absolutely has to — might as well hold the subs as long as possible, right? Never mind that the news is seeping out, and Sky, as a listed company, is required to immediately disclose any information that could materially affect its share price.

The topic is abandoned, half-digested. They talk game schedules and subscription uptake curves, holding pages and promotional videos. Dates are scattered throughout, though none appears quite certain which relates to what. Does the full site go live on August 7? August 9? August 10? “I made that date up,” admits Chesterman. “I make all these dates up. We’re messing round with dates like they’re birds in the sky.”

It doesn’t really matter. Technically and promotionally, all agree they’re on schedule for the first big date — the July 4 media launch. It is a little over two weeks away.

The following afternoon, Martin drives his new BMW to a meeting at Ponsonby ad agency Colenso BBDO. He’s there to give them the EPL pitch, and has sent non-disclosure agreements in advance. On the drive over, he calls TVNZ’s Jeff Latch (“What we need to know is the technical cost of Asia satellite”), with whom they’re negotiating a match-of-the-week deal, and Colenso, to apologise for his lateness. As we park, he tells me, “I don’t really know what we’re doing here.”

He’s lying. What he wants from Colenso is cash and profile. The agency work with some of the biggest brands in the country — BNZ, Tip Top, Vodafone — and Martin wants them to convince their clients to partner up with the EPL.

To run competitions which fly fans to games, give away subscriptions, take ads on their site. Anyone really keen could buy the naming rights — for a sum well into six figures. He settles at the head of the table in a vast, windowless meeting room and gives a speech now so familiar it glides off his tongue.

“With Coliseum, we thought that digital technology would fundamentally alter the basis of sport. The internet has ripped apart music. It’s changed TV. It’s changed music. We think sport’s the last one to go.”

Terry Williams-Willcock, an Englishman and Colenso’s digital creative director, nods in agreement. “Spotify has, in my mind, changed the way I listen to music,” he says. “I’ve lost the premiership since coming to New Zealand, and I used to be a massive fan.”

Given that the EPL has been on Sky the whole time, it’s a slightly obsequious statement. But Martin likes hearing it, and watching the room buzz at being let in on the secret.

Colenso’s creatives get it. They’re jazzed about the opportunities and vow to come back with ideas and approaches — and maybe that big naming-rights deal. Inner-city ad people, though, were always going to click. The great unknown for Coliseum is how middle New Zealand’s football fans will respond to being told someone has messed with their televisions.

As it turns out, Martin will find that out in a couple of hours: the story breaks on Facebook and is picked up by Radio Sport’s D’Arcy Waldegrave, who tries gamely to report in an information vacuum. “Apparently [the EPL rights] have been bought by an investment group who intend to on-sell them to the highest bidder,” he says, acknowledging his source as “what I’m hearing”. Twitter and Facebook go nuts, predictably, and by 5.30, Sky issues a statement confirming that, despite placing its “highest-ever bid for the rights”, it has lost the EPL.

“In the last few days we have been told that we have been outbid for those rights by what we believe to be a private equity company. We are also led to believe that they will be offering the games as an online package.”

Cricket commentator Navjot Sidhu once compared statistics to bikinis: “What they reveal is tantalising, but what they hide is vital.” He might just as well have been referring to facts about the EPL deal on the morning of June 19. The media boiled with wild conjecture. Freeview operator Sommet Sports had the rights, then it didn’t. The EPL had gone to a “British-based company, by the sound of it. Or maybe Middle East.” Or a shadowy “overseas-based consortium, totally new to the New Zealand market”. Sky founder Craig Heatley was back to haunt his former company. ISP Orcon might have bought the rights. The new owners were going to sell the rights back to Sky for a healthy profit. Obesity would spiral out of control!

They had made the decision to announce the deal the following day. That meant compressing two weeks’ work into 18 hours.

Coliseum watched all this with a mixture of excitement and paralysing fear. Late the previous night, they had made the decision to announce the deal the following day. That meant compressing two weeks’ work into 18 hours. Chesterman pulled an all-nighter to get a simplified version of the launch site ready for primetime, while Tim Martin worked with the newly hired Coliseum press officer, Elaine McNee, on the media launch side.

McNee is a former sports journalist and bandmate of Travis’ Fran Neely — “Why Does It Always Rain on Me?” they asked in the late 90s. As the pressure of the launch builds, she will handle Martin gamely, curbing some of his wilder instincts and helping to ground the whole organisation through this process.

The morning of June 19, Coliseum’s offices are controlled chaos. Martin keeps repeating the key line from his speech “It’s good news for football fans” with a wide, slightly manic grin (“No more coffee for me!”). There is still no contract with TVNZ. They have an agreement in principle, but the details have not been ironed out.

This deal is crucial to blunting criticism they’re taking the game away from certain sectors of the community: those off the internet or in rural locations beyond broadband — pensioners and farmers. You don’t mess with either. Coliseum wants this to be a story as much about the return of EPL to free-to-air TV as their pay service.

A deal with Telecom, whereby its customers will be offered discounted access, is also on the table, but even further away. “The people who are going to fuck this up are Telecom,” says Martin. Cockram makes Cooper and Co’s perspective clear. “Tell them, naturally, they can’t announce because the contract isn’t signed.”

Kate scans Twitter, to get a sense of where the story is going. “Pricing is what they’re all worrying about”. This is a source of some relief — the conjecture is settling between $180 and $200, but the entry-level package will be $149.90.

“I’m 15 years into an anxiety problem,” he says. “It’s just a dark traveller that joins you along the way.”

“Hi, my name’s Tim Martin, and I’m here to tell you about some great news for football fans,” Martin announces again, making his hands into pistols and firing at the wall. He wants to do this thing right now. Chesterman is far less excited. I ask him how he’s feeling. “I’m 15 years into an anxiety problem,” he says. “It’s just a dark traveller that joins you along the way.”

Martin’s phone keeps ringing. Just before 10am he hangs up and says, “My new suit’s ready. Should I go get it? Crane Brothers. It’s the money!”

TVNZ calls again — there’s a sticking point to work through, but everyone’s confident the contract will get signed. “I like that guy,” says Martin emphatically of Jeff Latch. Beatrice Lee has woken to the news in Singapore, and calls to talk about its ramifications. Martin heads into the boardroom to take the call. “We’re having a bit of a weird day, because the story’s broken that we’ve got the rights,” he booms. A secretary quietly closes the room’s door.

The markets open, and Sky’s shares plunge over six per cent from their close the previous evening. The company has lost more than $100 million in market capitalisation in just minutes. This, finally, gives Martin pause. “Fuck,” he says. Silence.

“I find that stuff slightly daunting. Suddenly it stops being about the sports fan, and gets a lot bigger.”

A little after 1pm, Cockram is handed TVNZ’s amendments to the contract. They seem minor but are fiendishly specific. It’s times like this the Coliseum guys extract immense value from having partnered with a gang of lawyers.

In fact, the legal background only hints at Cooper and Co’s scale. The business is a private investment company established in 1989 which “develops and invests in assets on a long-term ownership basis”. Founder Peter Cooper was a lawyer at Russell McVeagh during the 80s, and worked on mega-deals like the merger of Lion and Nathan, before moving his family to California in 1990.

At the heart of the company is Southlake Town Centre in Dallas, a 52.6ha development in the midst of the wealthiest suburb in America. Britomart is no small beer, either — the $500 million deal to revitalise Auckland’s downtown was reportedly the biggest property transaction in New Zealand history. Cooper and Co has diversified beyond real estate lately, through holdings in clean energy and financial services. And now sports media.

I met Peter Cooper on one of his regular forays back to New Zealand. He wore a butcher’s striped shirt and black silk knit tie, with a fetching silver quiff. We sat in the same boardroom where Martin sweated it out 18 months earlier, and he told me expansively that they look for businesses which are “scalable and sustainable”.

“We have to believe that there’s a tailwind behind you economically,” he said, and later, “We have to believe that we can add value beyond capital.”

Coliseum sits under California-based New Zealander Adam Mikkelsen’s private equity wing of Cooper and Co. “He’s a lawyer and a mathematician with a PhD in economics,” says Cooper admiringly.

At Coliseum HQ, with the clock ticking and the press conference looming, Cockram has completed his analysis of TVNZ’s proposed changes to the contract. His genial demeanour has turned grim. “Well, that’s just stupid,” he fumes. “They’re being fucking dicks. They’ve put this replay in… We don’t know if we can do that… This one is just complete nonsense.”

He decides to call them out. “Just send the original back to them and tell them to sign it as it was,” he declares, and heads for the door. On his way out, he catches himself, turns and smiles. “Got the message?”

Martin calls Latch. “Matthew didn’t like those changes at all,” he says, diplomatically translating Cockram. “He’s just not sure we can deliver. So he doesn’t want them put in there.”

He pauses while Latch responds. “I understand that. But what we’re not going to be able to do is bridge that gap right now. The way to do it is to append a term sheet that will move to formal contract afterwards.” Martin is learning the lawyer’s language.

The conversation lasts for perhaps five minutes. The changes are rescinded. The contract is signed. TVNZ has made the press conference. Telecom, which will become a steadfast ally in weeks to come, can’t make the deadline.

With 40 minutes until the press conference in a venue across the square, Kate arrives with the new suit. Charcoal with thin grey pinstripes. Martin loves it and whips off his trousers. Chesterman has his back turned. “Are you naked right now?” “Nearly,” says Martin.

“He’s going to sweat like a pig,” whispers Chesterman gleefully.

They head for the venue. “Teeth check,” says McNee. Martin grins broadly, but she finds nothing amiss. “Do you want a quick vodka shot?” she asks. Martin demurs.

Inside, there are a few dozen journalists assembled, with five TV cameras lined up at front of stage. At the back, Sky Sports host Dennis Katsanos plays the spurned lover, standing with his hands in his pockets, chewing gum and scowling at the lectern.

At 1.58pm, Tim Martin climbs onto the stage. “Why are we here today? I’m here to tell you that we have good news for football fans.”

Martin has been waiting years for this moment, and just wants to get at it. At 1.58pm, he climbs onto the stage. “Why are we here today? I’m here to tell you that we have good news for football fans…” He runs through the details. All 385 games will be live on Coliseum’s PremierLeaguePass.com site, with most available for on-demand viewing, and there’s a premium package with extras. TVNZ will screen one game a week delayed on a Sunday, just like the old days, with a highlights show on Monday nights.

Martin nails it. Something about his person is immensely reassuring: the accent, the suit, the smooth, tanned skin. Notwithstanding middle-aged white men’s depressing historical advantage on this front, Martin somehow looks like a CEO, and projects an ineffable air of confidence and security. “I’ve never met anyone who didn’t like him,” says Chesterman.

The appeals to nostalgia are perfectly pitched. “I remember watching the Premier League with my father,” Martin says, and instantly we’re back there on the couch with our own fathers. It doesn’t matter that Martin was in Laos, or Vietnam, or that it might never have happened. What matters is how the line makes us in the room feel.

He asks for questions, and there are a few curly ones. Is New Zealand’s internet up to it? (They believe it is.) Did Coliseum pay too much? (They don’t think so.) That honesty Cockram noted in their first meeting is still front and centre, as Martin admits the EPL might simply sell the games direct to consumers when the contract expires in three years. The press aren’t used to people admitting their business might be built on sand. They like it.

At the back of the room, Cockram has slipped in, and can’t stop smiling. “He did really well. What a star. He’s just a really nice man,” he says. “You can’t go far wrong with that.”

Chesterman, McNee and the Martins celebrate that night with beer and fried chicken. It’s a short night, though — the workload is spiralling off the back of the press conference. Meanwhile, a few miles south in their cavernous Ellerslie HQ, Sky has begun plotting a comeback. The incumbent broadcaster didn’t get big without knowing how to brawl.

The following morning, Martin heads in to The Radio Network for an hour with Brendan Telfer on Radio Sport. Off air, he’s greeted adoringly by their reporters and hosts, grateful for the endless talkback he’s precipitated.

Meanwhile, Chesterman is at the other end of the pipe: already, there are more than 4000 registrations of interest and thousands of emails — from thrilled potential customers and newly minted enemies. The latter can be vicious, and read like shit found poetry:

EPL belongs on TV

You money hungry lot should have stayed out of it.

I hope you go under

Leave the sports on tv take your internet crap with you

Chesterman spends two days replying politely to each one. He gains valuable intelligence around potential problems and their solutions, while losing sleep and his ground-ing in reality. By Friday, he’s had enough, outsourcing the job and calling in a mental health day to watch game seven of the NBA finals.

Over the next few weeks, Martin starts to look hard at future deals. For Coliseum, New Zealand is the beginning, but not the end-game — their eyes are on Asia. This is where Cooper’s “scalability” comes in. The EPL is only the first step.

Martin has also fielded a series of calls from some big, curious companies. Samsung and Panasonic, Noel Leeming and The Warehouse — and other football rights holders from around the world, wanting to know if he’s buying. Analysts from Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch and others call regularly for information to use in their valuations of Sky.

All requests are politely declined. Having stuck his head above the parapet, Martin is now on all manner of lists and, perhaps inevitably, there’s now a “Tim Martin for PM” Facebook page. “With the skeletons in my closet?” Martin shakes his head.

Over the following weeks, with the season launch looming, Chesterman continues to corral the tech, hone the design and massage the customers while Martin goes hunting for bigger games. Sky’s share price continues to fall, bottoming out below $5, from its pre-announcement price of $5.73, before rebounding to settle down around five per cent. That’s about the value the Labour-Green power plan wiped off Contact Energy when it was announced.

Sky’s CEO John Fellet affects a nonchalant public face, telling Fairfax Media journalist Matt Nippert, “It doesn’t do me any good to win every right at whatever price — eventually shareholders and customers would feel the pain.” Lawyer Michael Wigley writes in the NBR that Sky might be running a “tall dwarf” strategy, where they allow Coliseum to grow a little in the interest of having the appearance, but not the reality, of competition.

All this helps foster the impression at Coliseum that Sky aren’t taking them too seriously. On July 31, the mood is buoyant. The site has been live for a couple of days as a soft launch and it’s functioning as it should. There’s been some slightly hyperbolic criticism in tech forums, which Sky has helpfully forwarded to journalists (“I am absolutely amazed that this EPL season in New Zealand, I have no way of watching the premier league in HD and 5.1 sound. I feel like we have just moved back in time 10-15 years… It is an absolute disgrace”).

Chesterman says he was prepared for that and is ready to upgrade high-end capacity on the fly should demand warrant it.

Early the next morning, the day of the official launch — the day Coliseum starts taking money for subs — Sky drops a bomb. It’s found a backdoor into EPL coverage, buying the rights to screen Manchester City, Arsenal and Spurs games from the clubs themselves. It also says it’s negotiating with a fourth club. The announcement’s timing is exquisitely Machiavellian.

“They’re trying to drown the baby in the bathtub,” says Chesterman, who seems oddly calm. So do the others — even though Sky has announced it will continue to screen the games of four of the biggest clubs in the league. The lion’s share of the potential audience is attached to one or other of those clubs.

A 3pm meeting with Cooper and Cockram starts to reveal the details. Sky coverage must be delayed a minimum of 13 hours. For a channel founded on live sport, that’s an odd proposition. There are some other curly elements, such as three-hour game slots and staggered starts, which will make programming difficult, along with home-team commentary rather than Martin Tyler, hailed as the EPL’s commentator of the decade. The hardcore fan, who watches live or gets up and wants to “watch over cornflakes”, as Martin puts it, won’t be moved. But some casual fans certainly will be.

It was an inspired play, against the spirit of the EPL deal, if not the letter. The rights to club channels are scarcely valued in other markets and time zones, where they fall into the following day. In New Zealand, thanks to the live games happening in the wee small hours, they’re a different animal.

Sky’s director of sports content, Richard Last, says he knew about the clause, and intended to deploy it should Sky fail to gain the live rights. As to their party-pooping timing, he plays implausibly dumb. “Really? I didn’t know they were doing anything,” he recalls saying to a colleague. “They must think we’re doing it on purpose.” So much for tall dwarfs.

Martin is belligerent. “We’ve really kicked them in the nuts. They’ve come back and punched us in the face,” he says. “But that’s Sky. They’re being investigated by the Commerce Commission. That’s who they are.”

He warms to his topic. “Richard Last is just a guy spending a monopoly’s money. Is he still up to it? Is John Fellet still up to it?” Sky’s counterpunch suggests they are.

But Coliseum is genuinely upbeat. They’re having dinner with Indian Cricket representatives that evening and are launching another service within a couple of months, an “action sports” platform Sky couldn’t steal even if they wanted to. Beyond that, they’re circling still bigger prizes.

Later that afternoon, Chesterman tells me something else about the value of Cockram and Cooper’s backing. “It’s not the resources,” he says, “it’s the appetite. They love this stuff.”

In truth, they all do. Shortly before go-live on August 17, Sky announces the fourth club side for which it has rights: Man U. The big one. Martin, sick of Last’s crowing, fires back, telling the Herald subscription uptake is “in the thousands” and that come 2015, Coliseum will be going after Sky’s bread and butter: Super Rugby and the All Blacks.

Game on. This is a corporate battle playing out as a sporting contest. A dominant but ageing squad tested against a hungry young pretender. Neither is willing to be bullied, and both are up for the fight.

*[Correction: This story originally stated that NZ Cricket’s eight-year deal was with Sky Television, not Pitch International.]