Sep 30, 2014 Sport

Kevin Fallon is surely the toughest guy in New Zealand football. As a coach he’s won almost everything worth winning, and he’s lost most of the jobs he’s ever had, too. He’s just lost another one. Is he a hero, or a villain, or both?

First published in Metro, September 2014. Photos by Alistair Guthrie.

The plan was to have the youngsters train like professionals. Day in, day out coach Kevin Fallon would roll out of bed before dawn and head down to the Mount Albert Grammar football fields. Waiting there in the dark, the cold, the rain, would be a group of 30 or more young men. Many had come from across the city, across the country to be there.

Their self-belief met its match in Fallon, NZOM, the country’s most famous football coach. He carried with him the promise that if you submitted your talent to his technical abilities and iron will then there was no knowing where you might end up. Ten of his former charges have played for the All Whites, while many more have taken up professional contracts or scholarships to prestigious US colleges.

Fallon’s Mt Albert (MAGS) teams were notorious for their fealty to their coach, for the way they trained and played with the commitment of the professionals they aspired to be. That extended to the presentation of the dressing room, even at schoolboy level.

“‘Don’t do it that way, son – the hangers point that way. It’s like a dog’s bloody breakfast, the training room. Hey! Them hangers point left!’” says Fallon, mimicking his own reprimands. “So every hanger’s going that way. And the shirts are up, and the number’s showing, and the socks are folded a certain way.”

You put up with his fastidiousness, his intensity, his occasional anger, knowing it was the most reliable pathway to greatness in this country. Not just for the players, but for the school too. In 1997, his first full year coaching at MAGS, they came second in the Auckland secondary school’s premier league. The following year they won – for the first time since the 70s – and they’ve repeated that feat 10 times since. They’ve won over a dozen other key trophies in that time, including seven national championships.

“We’re arguably the most successful football school in New Zealand,” says Fallon of the era, before adjusting his position. “Actually I’ll take that back. It’s not arguably, it’s conclusively. It’s been like the Manchester United of school football.”

That glorious era is over now. On Thursday, July 24, MAGS sacked their Alex Ferguson. Fallon, a meticulous diarist, started the day’s entry thus: “As predicted, fired. Terminated. Unemployed. With no wages!”

It didn’t just impact the school – it made the front page of the New Zealand Herald. The dismissal of a high-school coach, even one as successful as Fallon, would normally not even register in the sports briefs. But Fallon is no ordinary coach.

He was assistant to John Adshead during the epic 16-game run to the All Whites debut appearance at the World Cup in 1982. He assumed national head coaching duties from ‘85 to ‘88, and has won almost every award and championship worth winning in this country, from the Chatham Cup to the National League.

The MAGS first XI were told privately, just prior to a game against Sacred Heart. They were reportedly in tears, and broke a three-game winning streak with an ugly, dispirited 7-0 trouncing. “They heard the news and went to pieces,” says Pete Jones, parent to a first XI player. The team hasn’t won since.

The reason for his dismissal was not publicly announced, but the rumour doing the rounds seemed comically banal. “The unofficial word is it’s swearing,” said Pete Jones. He wasn’t impressed. “You show me any top level coach who doesn’t swear.”

Julie Mata, mother to two first XI players, decided to do something. On an overcast Saturday in early August I found her standing behind a trestle table on the corner of New North Rd and Wairere Ave, alongside local landmark Rocket Park. Stacked high were black t-shirts with ‘BRING BACK KEV’ emblazoned across them in bold white letters. A tree had been turned into a makeshift mannequin, with t-shirts draped around it.

Business was steady, but not brisk. “It was a few drinks with my sister,” says Mata. On reflection, 500 might have been a few too many to get printed.

Nearly all the shirts they did sell appeared at that afternoon’s game between MAGS and St Kents, on the backs of parents and friends of the school’s football community. It ended in a 2-2 draw, but did not pass without incident, with MAGS head Dale Burden and deputy Paul McKinlay standing warily away from the MAGS crowd.

Carter Simpson and Jackson Gibbons, a pair of year 13s, had worn the t-shirts to the game. Gibbons is a former Academy member while Simpson has friends in the first XI. I was standing on the sideline when I noticed a commotion. A security guard was marching the pair off their own school grounds.

“We’re getting kicked out for wearing the shirt,” they yelled at Mata, who happened to be passing. “You’re shitting me,” she replied. “McKinlay says it’s offensive to the school,” said Simpson. “We’re going to Kev’s.”

Fallon means a huge amount to MAGS. The school wasn’t just another notch on his coaching bedpost – after 18 years, they were by far his longest tenure. The first XI initially threatened to boycott that St Kents game, but then arrived en masse to see him the Wednesday after news broke. “I didn’t have enough chairs,” says a clearly touched Fallon.

He received over 150 emails and dozens of texts from present and former players, and showed me a selection. Chris James, an All White who plays professionally in Europe, wrote: “To this day I owe you a lot for the lessons you taught me. Even though it was only a short period of time. Not only as a young footballer, but also becoming a man and being able to handle the football environment when I came to the UK.”

This from a young member of the current MAGS Academy: “It’s sad to see all the devastated, clueless kids at school. That leaves me, who came to this school to be taught football at a high level, now without our coach, and in excruciating hatred towards whoever was responsible for firing you.”

It was a common sentiment among the kids, who appear to feel a far stronger loyalty to Fallon than to the school.

Fallon scanning the messages on his mobile, his eyes glazing over. The school has taken back his laptop, so it’s his only communication device now. Whenever I visited his St Lukes apartment, overlooking the school’s sports fields, he would spend long uncomfortable periods slowly scrolling through the emails. A man adrift from the only life he’s ever known, consumed both by the memories of his career and by what he sees as the gross injustice of his ousting.

Simpson and Gibbons hardly knew Fallon, but felt strongly enough to face disciplinary action for showing their support. The effect on the first XI was more profound. Two members quit immediately, while the others took weeks to mull their future with the team. They remain under a temporary coaching regime, and parents are considering whether they’ll play school or club football next year. They miss Fallon terribly. “He treated my kids like they were his own,” says one parent.

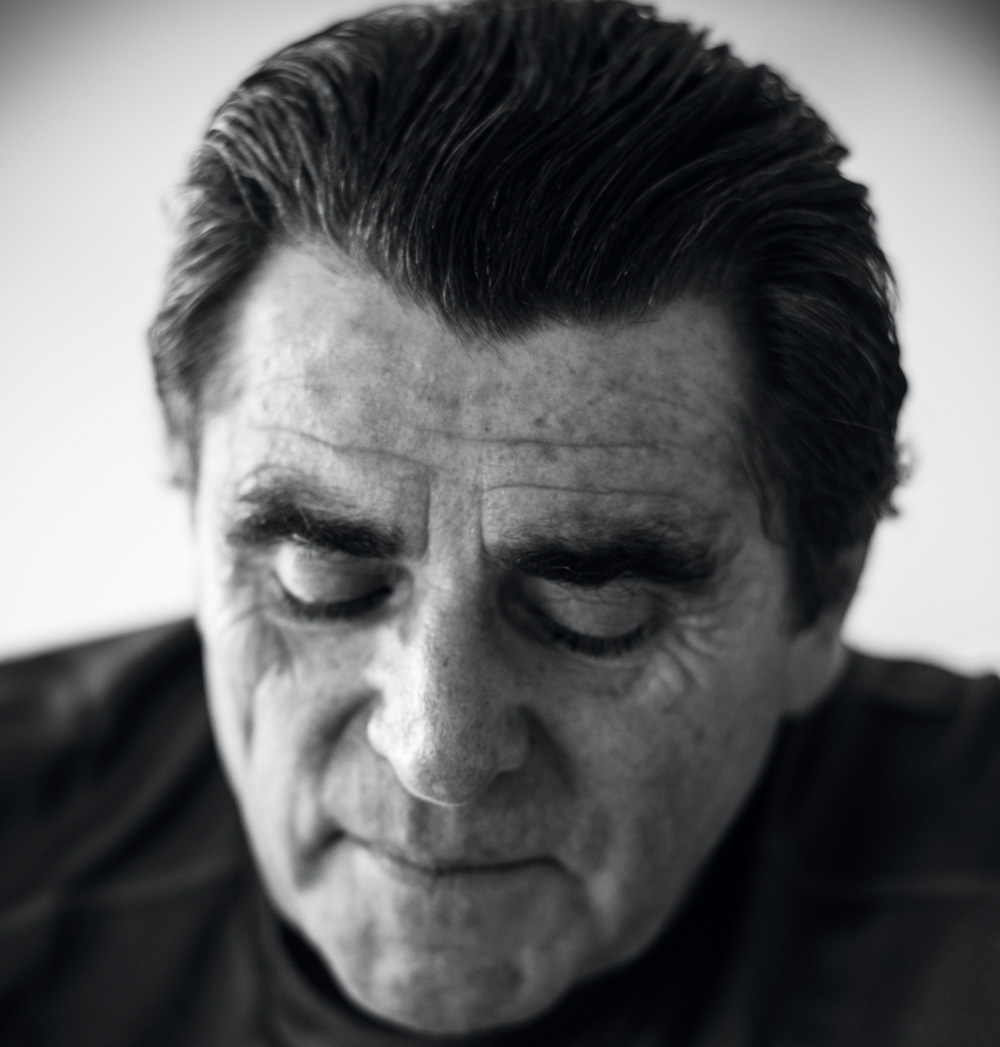

Fallon was named “personality of the year” five times by New Zealand Football. He still speaks in the broad Yorkshire accent he brought with him from the UK 40 years ago, and the first time I met him he was wearing Lotto sportswear head-to-toe, as if waiting for a call to get back on the field. His face is tanned by endless hours outdoors and his bearing is muscular and purposeful. He remains ruggedly handsome at 65, with thick black hair slicked back and greying slightly at the temples.

He’s charismatic, gregarious and charming – known as one of the best guys in the game to talk football with over a beer. Those chats are elevated by the breadth of his interests. There’s a biography of Norman Mailer beside his chair and a “collection of modern New Zealand poetry”, Broadsheet 13, on his coffee table. It’s a century of football verse, sure, but Fallon writes poetry and short stories himself too.

He adores Tom Waits and Lou Reed and owns every word Charles Bukowski ever wrote, along with dozens of the better football biographies. His self-image is a fusion of hard-nosed football maverick and hard-living 70s writer.

The second time I visited Fallon he read me underlined selections from Starmaker: The Untold Story of Jimmy Murphy, a key figure at Manchester United in the 60s and 70s. “Murphy hated the spotlight and preferred to be out on the pitch,” he read, admiringly. “Small, but a brilliant football brain, and bags of bottle.”

He stared lovingly at the pages. “There’s so much common sense in these words. To me it’s bloody magical. I’m just like him, I suppose.”

Now he’s uncertain and deflated. “There’s a big void in your life when there’s no football,” he says. “Football was never work. I used be up at 6.30 in the morning, skipping down that corridor. Ready to go. Ready for battle.”

In so many ways he’s the perfect coach. But there’s another side to Kevin Fallon.

“At the Nationals in Napier we played MAGS in a quarter final,” recalls Billy Harris, a former All White who has had a difficult relationship with Fallon, and was coaching Westlake at the time. “During the game, our 15-year-old sweeper Greg Williams did something which annoyed Fallon. Fallon called out something to Williams, who used the standard reply when you’re winning – which we were, by four goals – ‘What’s the score, Fallon?’

“Then followed the standard Fallon stuff: ‘You’re fucking rubbish son. You’ll never be a player.’

He’s not the only coach ever to give an opponent a spray, but Fallon’s outbursts strike those around the game as different. More vicious, more frequent and more personal.

The high stakes of the Nationals seem to bring out the worst in him. A few years back he allegedly yelled at one player with a birth defect, “You should be playing in a circus, not playing football!” He called a heavier player “you fat cunt”.

Then came the final, and an incident that has been reported to me by four different staff, from three different schools, who were present on the day – including a couple of people whom Fallon himself recommended I talk to, to get a sense of his style. To protect the identity of the player involved, certain details are kept vague.

Fallon had been told by another coach that a certain player was key to their attack, and that should MAGS be able to stop him, they would likely win the game. Fallon didn’t leave it to his players, he took responsibility himself. He spent much of the first half yelling, “Your mum’s a whore!” and, “She was sucking me off last night!”

Fallon knew the family well. He knew the mother had suffered a near-fatal health problem in the weeks prior. “Why are you talking about my mum like that,” asked the player, distraught. “You’re supposed to be friends with my dad.” The player was crushed and tearful at the half, locking himself in the bathroom, his head miles from the game. MAGS went on to win.

Fallon recalls it differently. “A ball went out of play. I gave [the player] the ball back, and I said to him, ‘When are you going to stop diving?’ And he said, ‘Fuck off, you twat.’ And that’s when I got stuck into him. I said, ‘You’re fucking diving all over the place like a big tart. Like your Mum.’ Something like that.”

Is that really so much better? He says he would have said the same to anyone, but is this behaviour appropriate for a game of high-school football? For a man in his sixties talking to a teenager?

The coach is unrepentant. “It was thrown out by the referees association. It was thrown out by the people at the tournament. It was thrown out by the secondary schools. There wasn’t an offence.”

MAGS headmaster Dale Burden ignored all that and took matters into his own hands, banning Fallon from the sidelines for the following year. Burden says he is confident something untoward had occurred.

605 " height="634" />

605 " height="634" />

These aren’t isolated incidents. Kevin Fallon was fired from his first player-coaching gig after brawling with teammate Ken Dugdale. He famously told the massed Australian media to “fuck off” mere months into his All Whites tenure. Grant Turner was so enraged by Fallon that he smashed his coach’s taillights. There are few who’ve played the game to a high level in New Zealand who don’t have a Fallon story or two.

The stories didn’t stop when he took the job at MAGS. Early on there was a complaint that he racially abused an opposing team. “I told them to go back to the jungle and eat their bananas,” Fallon admitted to the Herald in 2001. “On reflection, I should not have said that.” In the same story he claimed to be a changed man. “It is a different me,” Fallon says. “I’m more relaxed, more polite these days.”

If he did change, it didn’t last. Over the past five years he has reliably made the news every season or two for his antics. They’ve included a role in an all-in brawl, during which he put hands on one of Auckland Grammar’s players, leading to scene described as resembling “rugby league in the 80s”. The years since have seen complaints of such angry heckling of opposing players and referees, in 2013 he was required to see a school counsellor.

Ask Dale Burden why Fallon lasted so long, given his reputation, and he’ll tell you that he frequently had trouble getting an unbiased report. “I had to investigate an incident five years ago,” Burden told me, presumably referring to the brawl with Grammar, though he wouldn’t confirm it.

“Twenty people saw it. I couldn’t find a single reliable witness. Half the statements would start off with a page of offloading about Kevin, so it was obviously prejudiced. And his supporters were the other way. You’d think he’d just come back from missionary work in Africa.”

A senior administrator at another Auckland high school disputes this, claiming that they testified several times. “So that’s not true, to be honest. People have spoken up.” Additionally, Auckland Grammar signalled their dissatisfaction with Fallon’s behaviour in the starkest possible terms when they refused to participate in the Knockout Cup final in the aftermath of his involvement in the 2008 brawl.

As loudly as AGS complained, other witnesses contradicted them. More still were simply silent. That is part of the problem with Fallon. He’s been around so long and had such a high profile, much of the country’s football community has some relationship to him. Those who’ve coached against him say his aura is such that officials – often a third his age, and somewhat in awe – will turn a blind eye. And yet his achievements have engendered a loyalty as strong as any in New Zealand sport.

I spoke to a number of former opponents or people who’d been coached by Fallon, but few would go on the record with their misgivings. Some appear to fear his influence, particularly if they have sons playing, and some say they genuinely like Fallon away from the pitch. There’s another kind of fear too – and it’s not just of his brutal way with a putdown.

“I’ve never seen Fallon be physically violent,” says Billy Harris, “but as players in his team, with the stories of him thumping people, and the violent language he uses, he certainly has you thinking someone’s going to get thumped. I think he likes it that way.”

Sports people everywhere admire a tough, take-no-prisoners approach. But many – especially in school sports – don’t think that means the brutally aggressive behaviour Fallon has been known for.

“His behaviour really undermines all the good things he does,” lamented one football lifer. “He’s not really a good role model for kids. You’d have to ask Dale Burden why he survived so long.”

Burden has steered his school through a period of remarkable growth: at 2700, Mt Albert Grammar is now the second largest in the country. Sporting achievement – not just in football but in rugby, netball, rowing and many other sports –plays a big part in its reputation.

The ambitious principal and the even more ambitious coach. For a long time their goals were aligned. Until one day they weren’t. Neither will discuss the reasons for Fallon’s firing, but sources say a trio of events in quick succession finally ended his run.

First, there was an accusation of swearing at Westlake’s coach, which was disputed and ultimately not taken further by authorities. Next came a job appraisal which turned testy when Fallon was told his longtime helper Bobby Bland was no longer welcome with the team.

Third, a number of players were allegedly removed from class and asked whether Fallon had sworn in the dressing rooms. It’s near inevitable that some agreed – it wouldn’t be credible for anyone who knows Fallon in any capacity to say they hadn’t heard him swear.

It’s not really credible, either, that swearing is the issue. After 18 years of Fallon and all he represents, why pick up on that now?

It’s possible to see Burden in all this as both Fallon’s protector and his prosecutor. The man who kept Fallon on the job despite all the years of complaints; the man who sacked him this year.

Fallon, in a black mood, wonders if something more sinister is at work. “Is it age related? I’m 65 now,” he says. “And this trouble’s just conveniently wrapped up when you’re 65.”

There’s also talk that deputy head Paul McKinlay wants the first XI coaching role: he had the job at Westlake Boys. Fallon scoffs at the idea. “Oh dear,” he laughs. “That’s the funniest thing I’ve heard in ages. McKinlay? You must be joking. What he knows about football and tuppence won’t buy him a box of matches.”

Kevin Fallon grew up in the pit village of Bramley, the son of an Irish immigrant miner who worked seven days a week. As a child he saw more horses than cars on the streets, and even after turning “pro” at 17 he had to earn a living away from the game. He was bouncer at a Sheffield nightclub when the Kray twins, notorious gangsters, strolled in. He hefted meat at a freezing works, while training in the evening and playing on weekends.

Around Christmas in 1971, chilled to the bone after a day working a jackhammer on the roads, he received a postcard from a former teammate named Alan Vest. It was a picture of Young Nick’s Head, near Gisborne, the sky and sea brilliant shades of blue. Vest had written on the reverse, “How do you fancy some sun, surf and soccer?” Fallon was on a plane within weeks.

“I’m not being big-headed when I say that I took the game by storm,” he says. He won the Chatham Cup with Nelson in 1977, playing on despite having ruined his anterior cruciate ligaments not long after he landed here. On the pitch, what he lacked in style he compensated with sheer will.

“He was never an elegant player, and he’d be the first to admit that. But he was incredibly effective,” says former Auckland Grammar headmaster John Morris, who played against him in the 70s. “He was a very, very hard competitor. I’d use the world brutal, because that’s how he could be at times. But he’s a winner. He just wanted to win.”

In 1980 the new All Whites coach John Adshead asked him to be his assistant. The national team had, till then, suffered regular drubbings.

Fallon’s first game on the sideline was against Mexico at Bill McKinlay Park in Panmure. Few gave them a chance, but Ricky Herbert, Grant Turner and a number of other future stars were also debuting that day. Mexico were dispatched 4-0, and Adshead and Fallon’s All Whites would go on to qualify for the 1982 World Cup, football’s undisputed high point in this country.

After taking up the role at Mt Albert in 1996 Fallon continued to coach away from the school, taking the U17 All Whites to a famous victory over Poland in 1999, with a less successful stint with the A-League’s Football Kingz not long after.

Despite the wins, he’s not often stayed at any job too long. He’s fond of saying that “coaching’s a terminal occupation” – meaning that everyone’s always waiting to get fired. A partial list of teams he’s left acrimoniously includes Gisborne United, Hamilton AFC, Central United and The Football Kingz. Getting fired was part of the job – one he almost relished, until now. “I’ve always felt it was me against the world,” says Fallon. “I’ve always had that mentality.”

The great romantic, seemingly almost oblivious to the distress he causes. When I asked him about his reputation for getting into trouble on the sidelines, he praised his work ethic.

“What can you say about yourself? How can you judge yourself? You work hard, you’re successful. You’re always there, you never have a day off or anything like that.”

It’s as if he blacks out during these moments, or that his mind, unable to reconcile their relationship to the man he believes himself to be, simply deletes the memories.

“Most of the time he doesn’t know what he’s saying on the sideline, because he’s so bound up in the game, so passionate about it, that he doesn’t realise what he’s doing,” said one long-time observer. “It’s a really strange phenomenon.”

It’s always been a trade-off. He brings so much to so many. To most of his recent graduates, those who’ve trained under him, he’s a pivotal figure in their life. A man who gave football meaning, taught them discipline, fueled their transition from adolescence to adulthood.

To those who’ve felt his white-hot anger he’s an anachronism, a vicious, bullying pensioner battling children.

He spends his time now plotting his response, meeting with lawyers, imagining a court case that will win him back his job. After decades on the sidelines he’s finally on the field again. It’s not the game he wanted, but he’s got his boots on.