Jun 4, 2014 Sport

The international body count of professional sportsmen permanently harmed by repeated concussions is rising. Are New Zealand’s rugby codes doing enough to prevent harm to their players?

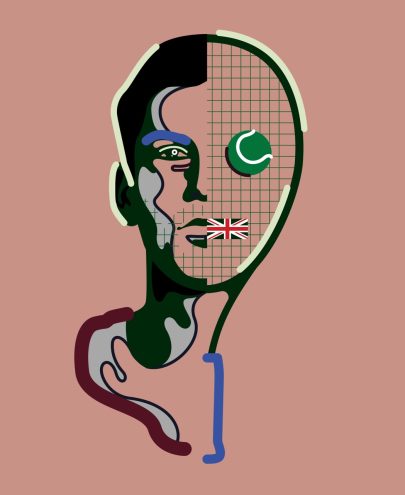

First published in Metro, June 2012. Above: All Black Ritchie McCaw is escorted from the field by team doctor John Mayhew during a Rugby World Cup 2003 match. Photo: Ross Land/Getty.

A few minutes after his girlfriend left their beachside California home for a morning workout in the gym on May 2, American football star Junior Seau reached for his handgun, pointed it at his heart and pulled the trigger.

A bullet to the chest rather than the head might seem an unusual choice for a man intent on suicide but in Seau’s case it made perfect sense. It was the third time in a year that a former National Football League player had taken his life this way — a way that would preserve his brain for research.

The sound of those gunshots are resonating around the world as the deaths, and dozens of lawsuits by NFL players who claim their brains were irreparably damaged by repeated blows to the head, change the way contact sports are being played and run.

And though we might think the rugby and league played by thousands of New Zealand men and boys here every winter bear no resemblance to the clashes of the helmeted giants of American gridiron, the former sports star leading the brain research effort in the United States told Metro this month that we are not immune.

Chris Nowinski, the former WWE pro wrestler who retired after repeated concussions and co-founded the Sports Legacy Institute in Boston to solve the sports concussion crisis, says having watched the All Blacks on television, he believes the risk of concussion in rugby is similar to American football’s. “Contact to the head in rugby is accidental and therefore likely occurs less frequently, but each hit can be more damaging, balancing out the risk.”

So what are our biggest sporting codes doing about this risk — and are the players who take to the field every weekend as safe as they should be?

One of Auckland’s most infamously brain-injured players is former All Black and Blues halfback Steve Devine, forced into retirement in 2007 after the last of many concussions, including being knocked out twice. “There were times when I felt I shouldn’t have been playing but I was — because I was needed.”

He’s suffered since with chronic migraines — now controlled by Botox injections — and depression but says he doesn’t follow closely the brain research news from the US because “it scares the shit out of me”.

While he’s satisfied with the protections now in place for professional players, Devine says he’s “horrifically concerned” for youngsters who might return to the field too soon after a head knock.

“Rugby is changing. Players are getting bigger, stronger and faster and the impacts are getting bigger. Even the impact in a scrum is huge.”

He doesn’t blame the game’s doctors or authorities for his years of ill health — he wanted to compete and sometimes minimised the effects of his injuries. As his career went on, however, the knocks he’d once recovered from the next day took longer and longer to resolve. In 2006, after taking three hard blows to the head in three weeks, he got home from training and went to sleep — in the hallway. “I knew something was wrong.”

Devine says the long-term risks of concussion weren’t well known in the early 2000s. “We got a hit to the noodle, you do a brain test and pass it and you’re all good to go.” There were even times he played on after briefly losing consciousness.

All Black captain Richie McCaw, who’s been concussed at least four times since 2004, doesn’t like talking about it since he was roasted for comments he made in 2009 saying that because he’d made a full recovery, he was no more susceptible to the effects of another concussion. Auckland neurologist and concussion specialist Dr Rosamund Hill told Metro the evidence was quite clear that there were long-term risks with multiple concussions, even if they were mild.

Most of us think of concussion in fairly simplistic terms: take a whack on the noggin and the brain shoots around inside the skull like a pinball, being battered, bruised and swollen as it bounces off the bone, causing symptoms including memory loss, dizziness, confusion, lack of co-ordination and balance, and even unconsciousness.

The reality is far more subtle than that and in most sports concussions, there’s no bruising or bleeding and no sign of structural injury on MRI or CT scans.

In fact, it’s the chemical and electrical functioning of the brain that’s disrupted when parts of it — some tethered by membranes, some not — move at different speeds as the head comes to an abrupt halt. Axons in the brain cells that conduct nerve signals become stretched and twisted by these differential forces, setting up a chemical cascade that inhibits the ability of the cells to communicate effectively with each other.

For years, concussion was thought of as a minor injury that rights itself within hours or days. But new evidence emerging from American courtrooms and research laboratories suggests the effects of repeated concussions — even minor knocks that cause only transitory symptoms — may be permanent and life changing. Concussions have been linked to early dementia, Parkinson’s Disease-like symptoms and even amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Players who claim the NFL negligently misled them about the dangers of concussions and other head injuries have filed more than 60 concussion-related lawsuits against the league.

While those responsible for player safety in rugby union and league say past attitudes to the “heroics” of playing on with injury have gone, others aren’t so sure. They point to the latest case of Warriors hooker Nathan Friend, who stayed on the field for 75 minutes after breaking his jaw in a game against Brisbane on May 5 — and was hailed by team-mates for his inspirational play.

“It’s come a long way, but more needs to be done,” says Wellington researcher, registered nurse and sideline medic Doug King, who earned a PhD in 2010 with a thesis on concussion in sport. “It’s a hidden epidemic and I think within 10 years we’re going to see the full effects of what we’ve ignored.”

He says he stepped down as a medic for a Petone league club after abuse from players and spectators over his hard-line attitude to concussion injuries. He volunteered at another five clubs but was told he wasn’t wanted as a medic. “I’ve been assaulted on the field trying to go and get a player who’s been concussed.”

King has since switched to rugby union, where he says attitudes to concussion are more enlightened. And yet it’s the National Rugby League (NRL), perhaps fearing a legal backlash from Australian players in response to the deepening US scandal, which has this year introduced tougher rules around head injuries, including fines for clubs that allow concussed sportsmen to play on.

This means an official reviewing a match on video could impose hefty fines for inaction — with the benefit of hindsight.

“It’s trial by video,” says Warriors and former All Blacks team doctor John Mayhew. He says the new policy has sent “shivers of alarm” through all NRL doctors. “I’m sure I’ve made mistakes where I haven’t recognised the severity of a player’s injury. Now if that happens, if you genuinely miss it, the club could get fined.”

But he says if a player is knocked out for 20 or 30 seconds, a club would rightly be in trouble for allowing him back in the game. “It has been up to the doctor’s discretion and I think the clinical judgment of some doctors gets swayed by non-medical factors — the coaches and what’s happening in the game.”

Further complicating matters in league is that unless the injury is major, lesser- qualified medics rather than medical staff go on the field when a player is hurt — the game usually continuing on around them. “Often coaching staff see this as a way of getting messages to the players and they want rugby league brains out there. If I go on unannounced, we can be fined. There needs to be some way of improving on-field diagnosis so people qualified in head-injury assessment can get on the field.”

Mayhew says he expects criticism over his decision to allow Nathan Friend, with the hooker’s consent, to play on despite being 90 per cent sure his jaw was broken. He says the call would obviously have been different if a concussion or neck injury had been involved, but in Friend’s case it was safe to carry on and he was not uncomfortable.

“I would have preferred the whole thing not to be given a lot of oxygen, because while we can make a decision in a controlled environment that it’s safe, will they do that tomorrow in the Northcote under-21s?”

Rugby union has its own problems with on-the-hoof diagnosis. Unlike league, which has an interchange system, a player who goes off for injury in a rugby union game is off for good. Although players can go to the “blood bin” to get wounds stitched or dressed and then return, there’s no “concussion bin” for assessment of brain injuries. That’s mainly because of the risk players will feign a head injury for a tactical substitution, as happened in the infamous Bloodgate scandal when English Harlequins players used fake blood capsules during the Heineken Cup in 2009.

Doug King’s been gobsmacked by the rule. “A few weeks ago, I told them I needed to see a player on the sideline for 10 minutes and they said, ‘Then he can’t come back on.’ The coaches were saying, ‘Well, you make the call, Doug, but we’d rather he stay on.’”

Around 1500 rugby and 300 league players have ACC claims for concussion accepted every year: the cost over the past five years for both codes is nearly $4.5 million. But the number who go undiagnosed or unreported is high — King puts the figure at 50 per cent, Nowinski at 90 per cent.

Nowinski told Metro that athletes remain poorly informed about the risks of concussion, particularly the new evidence surrounding the incidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) — a progressive, degenerative disease in people who’ve had multiple concussions.

A Sports Legacy Institute affiliate, the Centre for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, has studied the brains of more than 100 former athletes at post mortem — and 18 of the first 19 NFL players studied tested positive for CTE.

Like King, Nowinski is in favour of open substitution rules that allow time for players to be assessed on the sidelines.

Otago University researcher and senior physiotherapy lecturer Dr Tony Schneiders has been working on tests to assist sideline diagnosis, so medics have a less subjective measure of injury.

He’s hoping the Otago work will be among advances considered at a four-yearly international conference in Zurich in November to update guidelines on concussion in sport. He describes concussion as an unreported epidemic that’s “beginning to fester”.

Schneiders says that while the jury’s still out on CTE because of the “reasonably selective population” of brain donors, it’s likely some players are genetically more vulnerable to repeat concussions.

One man who knows that better than most is National MP Mike Sabin, whose son Darryl was almost killed by a head knock in a club game in Northland in 2009.

Sabin’s experience suggests that while elite players are well looked after when head injuries occur, supervision is less rigorous at junior or provincial level.

Darryl had a series of concussions in junior grades in his mid-teens but, because he wasn’t knocked out, didn’t think he’d been concussed. After he was hospitalised for half a day during one season, a doctor recommended he shouldn’t play for six months.

In his first game back the next season, in March 2007, he was knocked unconscious for 35 minutes and spent five days in an Auckland neurological ward.

“I got a few of my rugby mates together in Northland and we said to him, ‘Mate, your rugby career is over.’”

Sabin says he realised then that Darryl was suffering far more serious effects from head knocks that others could walk away from.

In December 2007, he took Darryl to Auckland City Hospital, where a neurologist scanned his brain and gave him a medical clearance, saying there was no evidence playing again would lead to further injury. “I was flabbergasted. It was like playing Russian roulette with five bullets,” says Mike Sabin. “I told the guy, ‘If my son plays as a result of the advice he’s got from you today and ends up seriously injuring or killing himself, just remember this time and my name because I’ll be back.’”

When Darryl told him he planned to play again, his father told the Rugby Union he would seek a court injunction to stop him. He did not get the chance. On Anzac Day 2009, in his second game of the season with his new Northland team, the then 19-year-old was knocked out and fell into a coma from which he was not expected to recover.

His father says while he’s “still the same person and personality”, Darryl today has stroke-like physical disabilities. “He realises he’s paid the price for his judgment.”

Sabin says he accepts his son’s case is extreme and unusual, “but the point is it wouldn’t be that hard to have a monitoring system so successive concussions can be red flagged.” Sabin wants referees to report such knocks to the Rugby Union.

“We’re learning more about the brain and the smart money will be on codes that identify the risk and manage it, mitigate it and look to prevent it.”

The NZRU says it’s doing that at all levels through its Rugby Smart injury prevention programme, in collaboration with the ACC. All coaches of players over 13 must attend an annual, compulsory safety education course that includes concussion recognition. Referees can also overrule coaches and send off a player they believe has been concussed.

NZRU community and provincial rugby general manager Brent Anderson says in under-13 grades, tackle techniques are taught progressively over weeks and months. Tackles at that age cannot be higher than the nipple line.

In many primary school games, “ripper rugby” is played. Instead of tackling their opponents, the children rip a Velcro tag off them.

The union’s senior scientist for injury prevention and high performance, Dr Ken Quarrie, says advice on concussion is rapidly changing with new research. The three-week mandatory stand-down has been replaced by a graduated medical clearance based on an individual player’s condition and recovery.

“With the stand-down, people were disinclined to report [injuries] because they didn’t want to miss three weeks for what they felt was an insignificant knock, so they would try to hide it. The other side was three weeks would elapse and regardless of their symptoms they’d be allowed back.”

Several years ago, Quarrie examined videos of 140,000 tackles in more than 400 high-level matches to determine which caused most injury. Unsurprisingly, head- and neck-high tackles were among the riskiest, and sanctions against those have been toughened accordingly.

“We’ve been addressing a desire of players and coaches to keep players on. The thinking now is when you’re injured, you don’t play as well. If you come back fully ready, you and your team will perform better. Coaches have really embraced that message.”

Warriors forward Micheal Luck, who retires at the end of the year, was knocked unconscious in a game against Parramatta in 2009 by a shoulder to his jaw. He says attitudes have changed dramatically in his 14 years in the game — the player who decked him wasn’t suspended “but in our game now, if he’d used that same tackle he would have been in trouble”.

In the past, Luck says, “it was an unwritten law that if you’re going to stay off the field you need to be pretty well hurt. I’ve seen guys who’ve been out cold go back on and play after half time, whereas no way today would you be allowed back on.”

But he says he knows damage can potentially be done in any tackle. “It’s a little car crash every time.”

Steve Devine, who now works as a fireman, is glad times have changed — even though the progress is too late for him.

“The risks were understated — I don’t think anyone knew what was going to happen to me.”

Of the deaths of Junior Seau and the other NFL players, he says, “Honestly, I don’t want to know. You give yourself a death sentence otherwise. If they were suffering what I’ve been through, it’s a horrible, horrible place to be.”