Sep 3, 2018 Property

Could it be that new greenfield projects aren’t the answer to Auckland’s housing shortfall and are actually part of the problem? Advocates of high-density living such as apartment developer Mark Todd are calling bullshit on well-worn claims about the need for more land.

Bernoulli is the first stop on a whirlwind drive around several of the maverick property developer’s latest projects, Todd’s response to a request for an interview about Auckland’s housing inequality. He talks a lot and without pause about the Auckland housing crisis, how he’s doing his bit to fix it and open people’s eyes to the benefits of apartment living, how difficult that is and what motivates him. We cover a lot of ground. He stops a couple of hours later when he literally runs out gas. “Too much talking,” he laughs. “I’ve never done that before.”

For now, as we push the car across the intersection and coast down the hill and up the other side until we can go no further, reality is shaping him. Unfazed, Todd talks steadily as we walk to a nearby gas station. He says he began Bernoulli Gardens about three years ago to show what could be done at Hobsonville, which was rapidly becoming just another elite unaffordable suburb. The average price of homes in this model — so-called medium-density nirvana — was heading towards $1 million.

Hobsonville wasn’t really within Ockham’s usual scope, which is firmly focused on urban regeneration, generally good-quality three- or four-, sometimes five-level apartment blocks in central but not CBD locations. Ockham apartments also tend to have weird names, often associated with mathematics or philosophy — Hypatia, Turing, Set, Ockham — and are mostly close to public transport, especially train stations. Todd recently called an apartment block Daisy. That caused broadcaster Mike Hosking to say that such a name was appropriate only for a cat or a dog. “Buildings should have bold names like The Empire, or The Statesman,” he opined.

Greenfield developments like Hobsonville, says Todd, are part of the problem. “The reality for most large-volume house builders is that the money is in the land subdivision, not building the house, which is kind of a dirty secret that drives greenfield projects.” He reels off a list of them: Kumeu, Huapai, Whenuapai, Silverdale, Stillwater, Papatoetoe, Albany, Long Bay, Pukekohe, Paerata. There’s no pent-up demand and most Aucklanders don’t really want to live out in these far-flung zones, says Todd.

What’s driving greenfield development, he says, is the buckets of money to be made by getting and rezoning land, putting infrastructure in and delivering the individual land title. In Todd’s view it’s 35 years of this free-market, laissez-faire attitude that has led to house prices becoming twice as expensive relative to income as they were 10 years ago. “Most players in the property sector have no interest in whether the houses they are building are relative to the social-economic-demographic needs of Auckland,” he says. “It’s not Aucklanders who are asking to live in these high-value greenfield locations, it’s land developers that agitate real hard and have got this ideology that’s been accepted that it’s all about supply and demand. It’s complete bullshit.”

This is what Todd calls a “big myth” — that 50-60 per cent of the cost of housing is in land and that the solution is to release more greenfield land — that Bernoulli Gardens dispels. It’s a position long promoted by organisations like Demographia, which publishes annual housing affordability surveys that promote private car and urban sprawl over increasing rail services and density. It’s a worldwide argument perhaps best represented at the extreme end by Zaha Hadid Architects’ principal Patrik Schumacher who, in an essay entitled “Only capitalism can solve the housing crisis”, argues that housing provision suffers from too much rather than too little state control. He argues that the restrictive and reactionary planning system should be replaced with self-regulation, overseen by property owners, and that market forces should be allowed to determine where and what type of housing is built.

Todd holds a strong counterview, as does Pip Cheshire, a past winner of the New Zealand Institute of Architects gold medal: “We have got to stop seeing houses as commodities,” Cheshire says. “We have to understand them as part of our national wealth in the way we see a railway system or an airport or something like that. They are too complex an issue for the market to provide.”

Yes, land price is driving house cost if you think of only stand-alone single houses or even terrace-house dwellings, but the equation gets turned on its head if you bring in real density. Todd says for his projects land generally accounts for 8 to 12 per cent of the budget. He cites three recent examples: Tuatahi in Mt Albert, where the land cost per unit was about $40,000, and Set in Avondale and Bernoulli in Hobsonville, where it was about $50,000.

At Hobsonville we drive by and then through a terrace-house development adjacent to Bernoulli. “Generally, this is what a super-lot looks like. There are three-level terrace houses on both sides. The street face looks all nice and pretty,” says Todd. “But look inside the lot. It’s all concrete driveway because there is a car that goes to everyone’s house. There’s no green space here; everything is covered in concrete.”

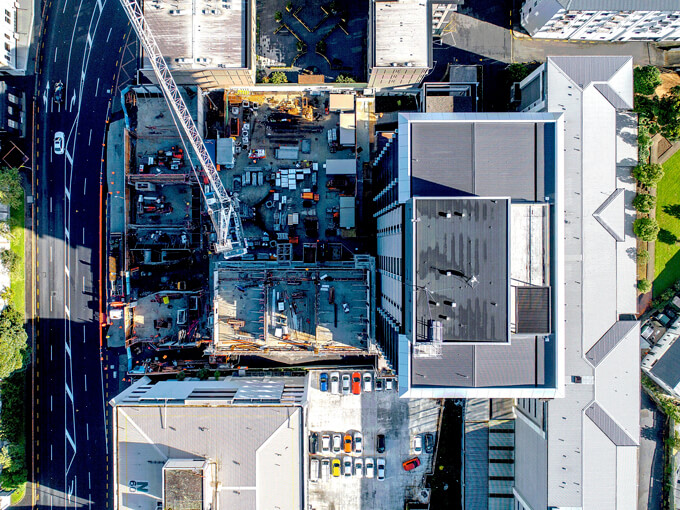

As he points out, the Bernoulli lot at Hobsonville was zoned for 43 terrace/town houses, which would have been an average of $900,000 each. “With the new Unitary Plan response, we have got 120 units with an average price of $615,000.” The complex comprises four three-level brick blocks of “character flats” with curved corners arranged around a central green space, and side “pocket parks” separating the buildings fronting Hobsonville Point Rd. All the car parking is collectivised under one of the buildings. “There are no concrete alleyways and a concrete centre, so we retain green space — 1200sqm of land collectivised — and an 80sqm kitchen/lounge common space.”

As well as a better design outcome in terms of shared green space that the residents can decide to use in a variety of ways — vegetable gardens, tennis courts, pool etc, Todd likes the underlying mathematics. “Instead of 43 x $900,000 for a gross value of $38.7 million of sales, we are 120 x $615,000 and our gross sales are $73.8 million. On the same lot I’ve actually generated more profit at 0.6 of the cost and three times the yield — three times the actual number of houses.” He gets a lot of satisfaction out of proving people wrong, he says. “It just requires a bit of ambition — we want people to copy us. That’s why I do it. I want to show it can be done. Sometimes I just do it out of spite.”

But Todd is equally clear that while around $600,000 might be the new normal affordable-housing price point, it’s actually still very expensive and out of reach for many. “This is the best I can do on a purely commercial basis. The average price across Ockham’s portfolio is $630,000. But $630,000 is not that affordable to most people.”

His thoughts are echoed by Salvation Army senior social policy analyst Alan Johnson, who recently told RNZ National’s Morning Report that the price cap of $650,000 for a three-bedroom KiwiBuild home in Auckland could not be described as affordable, especially if that requires a 20 per cent deposit of $130,000. That was in reference to the Government’s KiwiBuild policy, which promises to build 100,000 affordable homes over a decade.

The first 30 stand-alone KiwiBuild homes are at Housing New Zealand’s 600-residence McLennan project in the Takanini/Papakura area. The KiwiBuild price list shows: $499,000 for a two-bedroom home, $579,000 for a three-bedroom home and $649,000 for a four-bedroom home. Generally, a house-price-to-income multiple of three is seen as a good measure of housing affordability. In relation to the median household income in Auckland of $97,300 it’s a very unaffordable ratio of nearly six for the three-bedroom home, so there’s clearly room for improvement.

Similarly, a Housing Affordability Measure benchmark recently published by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment shows 79.86 per cent of all renting households could not comfortably afford a first home, with 84.23 per cent of Auckland renters unable to afford one.

Todd takes a macroeconomic view. “House prices relative to income, which is a key metric that’s closely correlated with lots of healthy outcomes, has been decoupled: house prices are twice as expensive relative to income as they were 10 years ago and the government has done nothing about it.” The reason? “Because workers don’t get paid enough. They are not getting their share of a modern economy which is highly productive and generates huge amounts of wealth, but it’s not collected and distributed in any meaningful way any more. Housing is just a prism where you see that neglect.

So if that’s the best that can be done on a commercial basis, you’d have to say the commercial basis is not really working very well. Unaffordability is the new normal. “One of the constraints of the sector is that to finance a large-scale project, the bank requires you to make 25 per cent margin on cost,” says Todd. “I don’t get to sidestep those hurdles. I have to be just as profitable as the next guy.” So could the government or Auckland Council help? “If I could get support to scale up, if the government underwrote some of the market risk, potentially you could build then on half the profit margin if you have a guaranteed purchase.”

Todd does the maths. “I’ve got to make 25 per cent on cost, so for $600,000, around $100,000 is profit. Sales and marketing is about four per cent — $25,000. Take that out and half the margin means $75,000 is taken out. What was $630,000 is now $560,000. That’s a huge step in the right direction.”

Another step in the right direction is Ngati Whatua o Orakei’s Kainga Tuatahi, a 30-house two-storey development on both sides of Kupe St at Bastion Point, which replaced 12 run-down state houses. The new dwellings — a mix of four-bedroom and two- to three-bedroom terrace units — are set in blocks of three or four and arranged around two communal outdoor gathering spaces that contain playgrounds, barbecue areas and vegetable gardens. “This is Maori building for themselves on their own land,” says architect Nicholas Stevens, of Stevens Lawson Architects. “What has stopped them doing this in the past has been the communal ownership of their land. The banks would not lend money on a place they can’t take back themselves.”

The solution Ngati Whatua came up with was a mechanism where the iwi effectively acts as a guarantor to these residents’ mortgages. The owners are all of Ngati Whatua descent and the land is leasehold with rules around reselling — properties can’t be sold on the open market. With land profit taken out of the equation, quality housing was the outcome at a cost of $418,000 for a two-bedroom townhouse, to $680,000 for a four-bedroom home. Kainga Tuatahi is the first stage of a development that could see about 3000 people living on the surrounding 16 hectares of iwi land.

A similar rethinking of how to provide affordable housing is also underway at Hobsonville, where Ngai Tahu Property, teamed up with the New Zealand Super Fund and New Ground Capital, has begun its Kerepeti project. Forty-seven of the homes will be retained by the consortium as rentals, with lease terms of up to seven years to provide security of tenure, plus the ability to shorten their lease should circumstances change. The consortium is also offering affordable homes priced from $450,000 to $550,000.

Todd is quick to point out that a key to unlocking this density potential and its impact on the value of land is the Unitary Plan.

“Sure there are issues with productivity and building material costs, but we don’t have any significant planning issue left any more. The Unitary Plan is surprisingly progressive.”

Before the Unitary Plan came into effect, the rules followed a density-based approach of one house per 400sqm. “That just economically precluded me from building anything other than large seven-figure townhouses.” With the Unitary Plan the big change is in the existing suburban environments. “No one is forcing you to build affordable housing, but at least it’s now in the solution space. I’ve got a choice.” The pent-up demand Todd sees is mainly for one- and two-bedroom units, which is why Bernoulli is 90 per cent sold before it’s complete.

He points out, too, that the Unitary Plan is a democratically created document. “Auckland has said we want 70 per cent new housing within our existing city footprint. That was a collective decision made through a public process.”

The Unitary Plan also no longer legislates carparks with density, which allowed developments like Daisy, one of the first special housing areas to take advantage of the new rules. “That site was brought into the solution space primarily because I have choice whether I put car parking in or not.” If the plan had kept legislating car parks, it immediately makes apartment development more expensive because car-parking space, especially underground, is costly. Without the no-car-park option, the site on Akepiro St beside Dominion Rd was also too small for development. “Auckland is an old-fashioned city. A lot of the titles are very small and you can’t develop discrete sites because you can’t meaningfully get parking on, so it was really holding development back.”

Such new thinking takes time — perhaps 60-70 years to become like Sydney, Melbourne and London, where most inner-city urban dwellers don’t have cars. With good public transport, and a future inhabited by Uber, Zoomy, e-bikes, rentable e-cars and autonomous vehicles, a carless choice isn’t a problem for inner-city dwellers.

Todd is a big fan of the urban-regeneration ethos of the Unitary Plan. He believes affordable apartment housing should be located in key town centres like Otahuhu, Panmure, Manukau and Henderson. “They’ve already got the civic infrastructure to be thriving town centres. We don’t have affordable housing located at density around those centres. It needs to be seeded.”

We stop at Set, three apartment buildings (subsets) at the edge of the Avondale Racecourse, with open-air parking at ground level. The Subset A and Subset B buildings are three-level walk-up brick and masonry in a character-flat style, with Ockham’s trademark decorative elements on the facade. Subset C is a six-level apartment building with western views over the racecourse and includes a ground-floor residents’ lounge and communal garden for all Set residents. One-bedroom apartments start at $560,000, two-bedrooms from $640,000. Again, most are already sold before completion. The site, owned by Auckland Council’s Panuku, could have been developed with 26 terrace houses. The Set development provides 70 dwellings.

Beside Set is a huge Housing New Zealand block of about 20 run-down single-level units and beside that a tract of vacant lots fronting Great North Rd. Todd states the obvious — that Set is in the heart of the dilapidated Avondale town centre and only two blocks from the train station. “You could build 2000 apartments here. Get that done and this would be a proper town centre like Ponsonby Rd.”

Next stop is Tuatahi in Mt Albert, in the hands of the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment as part of the surplus crown land for housing projects. Situated beside the new Waterview shared cycle path, close to Unitec’s Mt Albert campus and within walking distance of two train stations, it comprises 119 apartments in three buildings surrounding a large communal garden featuring a pool and a two-level community facility. Studio apartments start at $435,000, one bedroom from $530,000, one bedroom and study from $545,000 and two bedrooms from $620,000 — also largely sold before completion. Todd says the shared facility is a key feature and here he’s trying something new — a study space/library above the residents’ lounge. “I’ve never done a library before. We’ve sacrificed four apartments, $2.2 million in revenue in those spaces, but we are still making money. I’ve found the residents’ lounges are used a lot.”

What this adds up to is a different definition of medium density in order to achieve the current accepted norm — around $600,000 — of affordable housing in Auckland. For Todd, the definition is abundantly clear: “You don’t get medium-density housing until you make a collectivised decision. You’ve got to collectivise the car parking by putting it all in one place and unless you have got multiple dwellings off one entrance, it’s not medium density.”

Denser living. Aucklanders seem to be embracing it in droves judging by the number of apartments in the central city now so regularly advertised. A key feature of the new skyline is good design to show tower-block living as luxurious and desirable.

Cheshire Architects’ conversion, with developers Lamont & Co, of the 1970s former Winstone’s office tower near the corner of Symonds St and Khyber Pass Rd into a 12-storey luxury apartment building is a good example. While some of the lower-level units with no views — dubbed Warehouse apartments and featuring a 3.5m-high stud and open plan except for an internal “service box” incorporating bathroom, kitchen and storage — just scrape into the affordable category, everything else doesn’t. As the advertising puts it, the “apartments enjoy elevated city living saturated in some of the most extraordinary views of the city”. Indeed they do. I look at a three-bedroom corner apartment on the seventh floor which provides an unexpected close-up of Maungawhau/Mt Eden and long sweeping views of the city to the Waitemata, Manukau Heads and the Waitakere ranges.

As well as the tower apartments, which climb in the multiple-million-dollar realm the higher you go, Skhy features a range of apartment types combined with retail and commercial tenancies arranged around a landscaped courtyard at its base and connected by laneways off Hohipere St and Khyber Pass Rd. Among the courtyard-apartment types on offer are 80sqm plus 8sqm balcony, two-bedroom units spread over two floors, in a style inspired by Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille. When these were selling off the plan, they were a bargain at $800,000. With building underway, the price range is between $900,000 and up to $1.2 million. Density at a price, not unlike what it costs for a terrace house at Hobsonville.

But while Skhy is clearly showing Aucklanders that density is good and apartment living can be sensational, it’s not exactly helping with the housing crisis. In fact, you get the sense it may be contributing to it. On the seventh floor the new owner explains the move is a downsizing from a family home in Pt Chevalier. But it’s also very much a second dwelling — the first-time apartment owners split their time in the city with time at their other home about an hour north of Auckland — a familiar narrative among luxury apartment dwellers. Density dispersed.

On Auckland’s Hobson St, a stream of cars is headed for the motorway at the beginning of the evening rush hour. Outside the Auckland City Mission a row of mattresses lines the footpath. There’s a chill in the air and rough sleepers are bedded down for the night huddled in blankets and sleeping bags among bags and other possessions.

This is the brutal face of housing inequality in Auckland. No one knows the numbers. In June, Auckland Council announced it would carry out a census of homeless people in September.

In May, the Government unveiled a pre-Budget $100 million plan to tackle homelessness, including making 1500 transitional and emergency homes available this winter.

In a few months’ time, building will begin on Auckland City Mission’s Mission HomeGround, an $85 million project that will incorporate 80 units over five floors of accommodation for rough sleepers, two floors of detox facilities and a variety of “wraparound services” and community spaces.

Ironically, the design is not unlike the Skhy complex. At ground level a circulation spine — comprising the medical centre, which includes dental and mental health services, and the community facilities including commercial kitchen, meeting and activity rooms, showers and a cafe — creates a long internal laneway stretching between Hobson and Federal Sts. “Philosophically, it’s about the mission being more open and having a real engagement with the city,” says architect Nicholas Stevens. Accommodation for 110 people and the two detox floors rise above in an eight-level tower. At the top, instead of an eye-wateringly expensive penthouse as occurs in Skhy, there’s a common room and rooftop terrace with vegetable gardens and a greenhouse for the people who live in the building. A rooftop reversal and a refuge for those inhabiting the margins of urban life, but also a powerful statement about Auckland’s housing inequality.

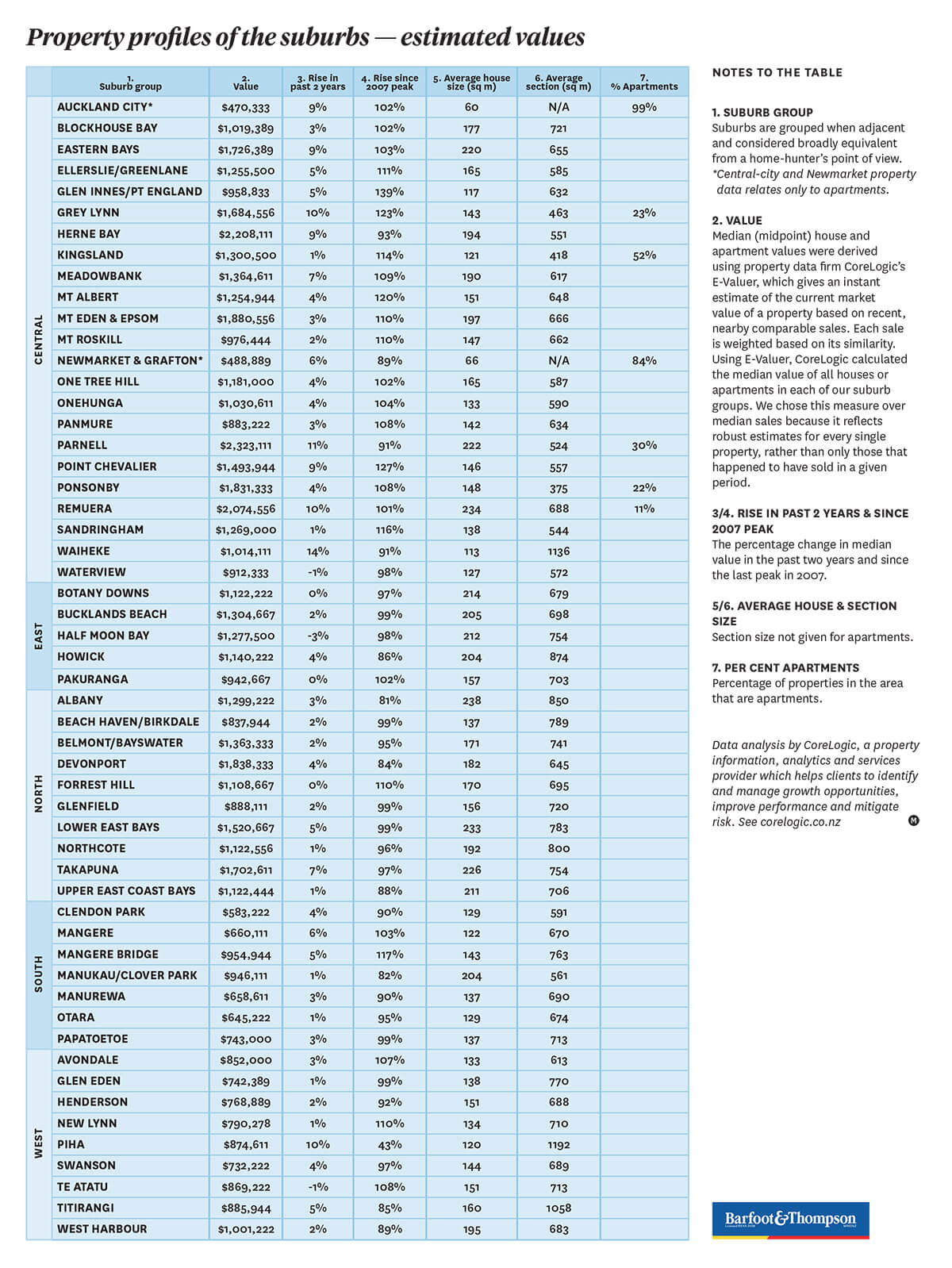

Barfoot & Thompson expert analysis

![]()

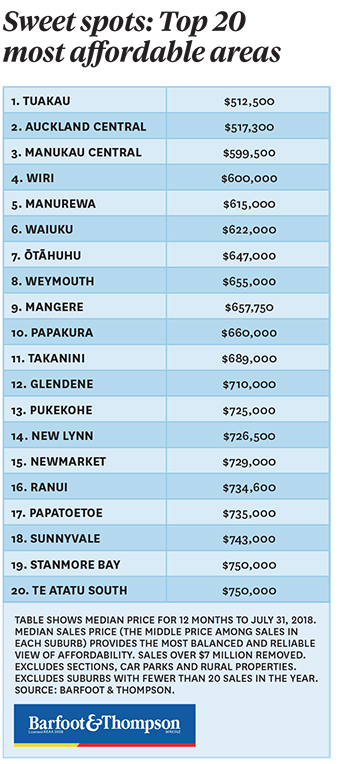

Foot on the ladder

What it really means to be entry-level in the Auckland market.

Tim Carter, Manurewa branch manager

In Manurewa, our average sale price is around $675,000. Most of the people who come to us looking to buy are in that price range — and they’re first-home buyers or investors. There’s plenty of opportunity here, and in nearby Takanini. We’ve got a great community-focused development, the McLennan project, which is aimed at first-home buyers.

It’s common, and really practical, to buy through KiwiSaver, but it does mean that it’s harder to buy at auction, as this requires you to be unconditional. While we’re seeing a rise in the “Bank of Mum and Dad” in Auckland, with parents pitching in to get their kids into their first home, out here in Manurewa that’s always been the way. It’s not just mum and dad, it’s entire families helping out to get a young couple over the line.

When looking ahead, a lot of how the market progresses will depend on what the Government does in regards to legislation — as well as the stock that’s available. Here in Manurewa, we sell a lot of older homes, many are ex-state houses and the reality is that they’re often a bit of a do-up. Many properties are also being redeveloped under the new Unitary Plan. It’s interesting times.

For the younger people wanting to get into the market, they’ve simply got to start saving as soon as possible — and be realistic about what they can afford. Your first property is not going to be a four bedroom, ultra-modern home, so it’s good to see your first purchase as a stepping stone. The idea is to just work on getting into the market, and once in you’re in you can gradually start to move up to the next level.

At Barfoot & Thompson, we’re seeing young couples who came to us for the first time three or four years ago and now they’re selling, with the ability to buy something much better than their first home. Often they’ve put a lot of effort into the property to get it up to a higher standard — it’s an exciting next step for them.

With property, it’s not where you start, it’s where you finish.

On top of the world

The Auckland market is up there with the best — for better or worse.

Peter Thompson, managing director

At Barfoot & Thompson, we’re very much involved with the Leading Real Estate Companies of the World (LeadingRE) organisation. We’re one of only two New Zealand firms invited to join. As well as being a source of global statistics, information and support, the organisation acts as a referral network. Vendors are put in touch with quality real estate agencies and people all around the globe that have the opportunity to look at their listing.

LeadingRE has noted that there is a big shift globally away from countries such as the United States and United Kingdom. We are now seeing India and China and the Asean countries, which include the Philippines and Vietnam, as the biggest property-growth areas over the next 10 to 20 years.

Auckland has come out of its shell over the past decade and is now seen as a major city of the world, with house prices here much the same as they are in Sydney, Melbourne, Vancouver or London. In London, half of all properties are now rented, while in New Zealand, a third are rented and two-thirds are owned. It’s clear that the movement to rental is significant in major cities.

In terms of foreign buyers in New Zealand, the Overseas Investment Amendment Bill makes a change to who can buy property in this country. But ultimately, as a small nation with a population still under five million, we do need people to come here to live, work and buy homes.

Auckland, like all the major cities of the world, faces issues of population growth, infrastructure and transport. Even so, New Zealand is seen as a safe haven and the threat of global issues — whether financial, political or even a natural disaster — will certainly continue to bring people to our shores to build their lives and buy homes.

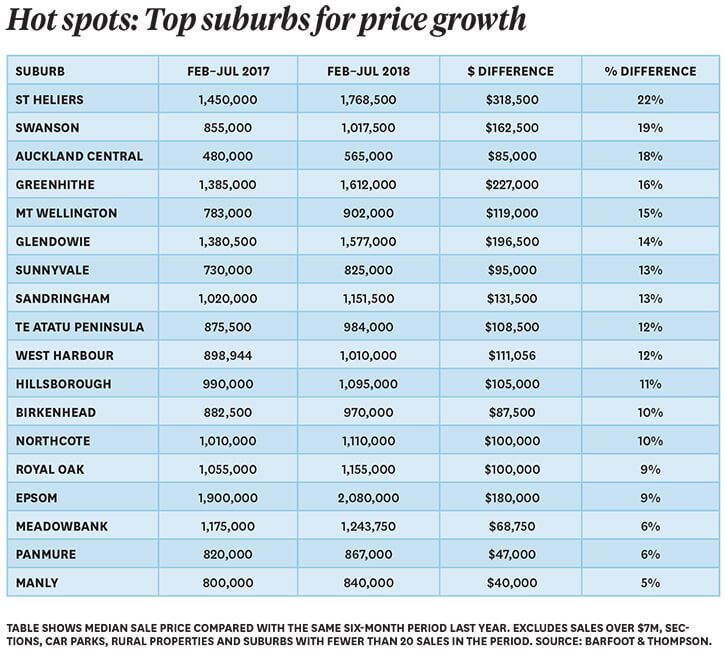

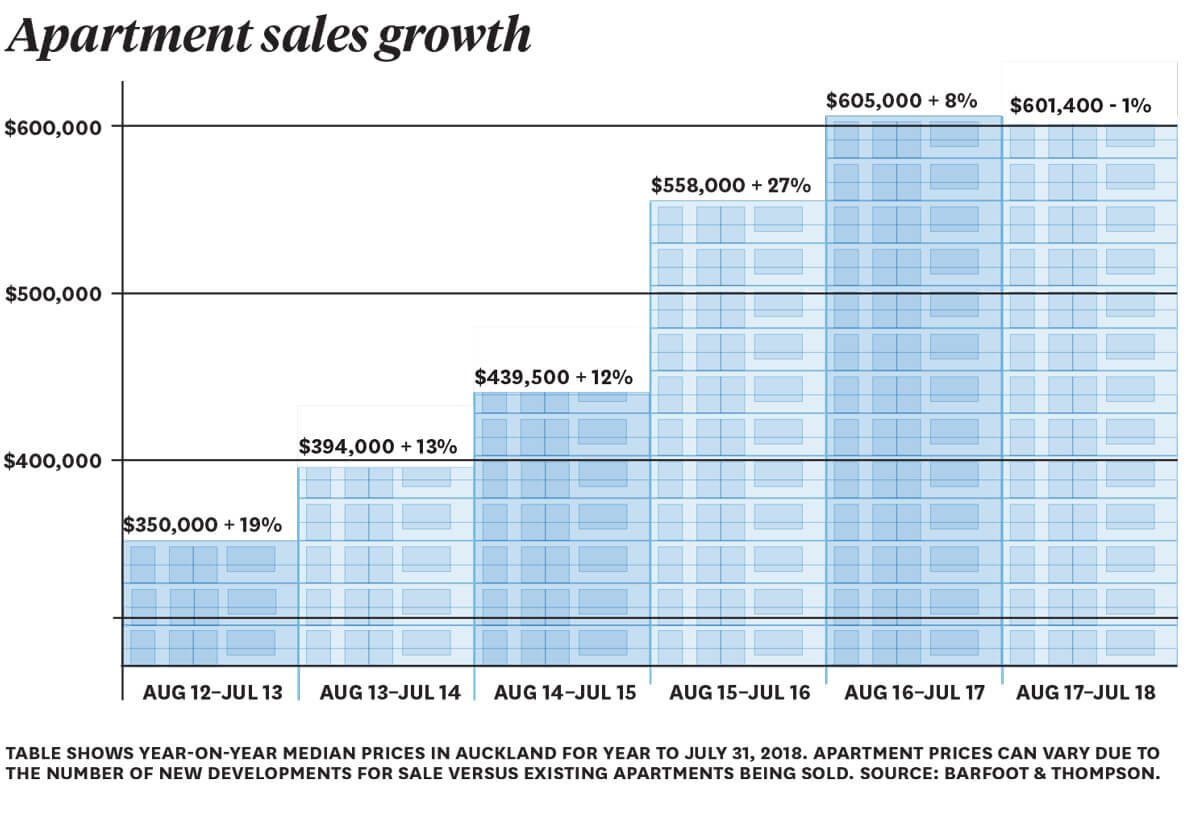

On the rise

Apartments are now seen as a great value-for-money investment.

Matt Baird, Auckland projects manager

There’s been a big shift since I started in property in the 90s. We’re now seeing larger, more design-focused apartments and there are a lot more owner-occupiers. What’s nice to see is that today’s buyers are discerning, they’ve travelled and have an appreciation for how great apartment living can work. On top of that, the good developers have got better and they’re really meeting the demand of the public. They’ve unlocked new parts of the city such as Wynyard Quarter, the Viaduct and Britomart, which are great places to live, work and play.

Owner-occupiers expect a quality product with good amenities. If they’re going to sacrifice 200 square metres for 100, they will, but only as long as it’s well designed and meets their touch points. As you can probably guess, many of the high-end apartments — the ones with concierge services, cinemas, wine cellars and pools — are being sold to baby boomers who expect high quality in a good location.

We used to have to sell people first on the idea of an apartment, then the apartment itself. That’s just not the case any more. The city fringe remains popular, and in the CBD the tower blocks offer a range of options from entry-level stock to high-end penthouses — along with the views that we’d all like to enjoy with apartment living. There are great small-scale developments in the suburbs, too, with developers targeting sites on ridgelines, so look for those sites if an apartment with a view is your goal.

The young professionals we see considering buying an apartment are asking themselves, “Do I buy a house in the suburbs for the same price or do I get something that’s smaller, is lock-up-and-leave, and that means I can spend more time with my friends and less time in traffic?”

The answer to that is usually to choose a great apartment — and there are plenty of options.

High costs burden

Everyone agrees New Zealand has a problem but few can agree on a solution.

It’s impossible to write about housing affordability in New Zealand without getting into a debate about our high building costs. But while our Productivity Commission has estimated we pay between 20 and 30 per cent more for building materials in New Zealand than people do in Australia, there’s disagreement on how to solve the problem.

Businessman Tex Edwards, founder of 2Degrees Mobile, recently chimed into the debate, claiming the construction sector lacks real competition because it’s dominated by just a few large players such as Carter Holt Harvey and Fletcher Building.

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment has calculated that New Zealand has a housing deficit of 71,000 homes. The huge shortage has led many to argue for a radical rethink in how we build, including a move towards more prefabrication. Housing Minister Phil Twyford seems to agree. He hopes more than half of the Government’s 100,000 KiwiBuild homes will be made by prefabrication and has asked companies here and overseas to express their interest in setting up, or expanding, off-site manufacturing factories to make homes for the scheme.

In an article for The Spinoff, Edwards argues: “We need rapid adoption of large scalable industrialised building techniques, where one or two factories are built to deliver 5000 to 8000 houses a year per factory. This is only possible with a Government contract, as it’s an industry change which needs scale to drive it.”

He believes KiwiBuild could be the beginning of such large contracts and says the Government should acknowledge market failure and intervene in the industry. He wants to fight monopoly with more monopoly. Good luck with that.

Ockham Residential’s Mark Todd is sceptical prefabrication is the panacea, but agrees that the New Zealand construction industry is under terrible strain and struggling to modernise. “We are a very unproductive sector.” He says the biggest problem he encounters is the lack of skills from top to bottom. “It’s really hard to get a competent site manager and it’s really hard to get competent sub-tradespeople — builders, plumbers, painters, stoppers, tilers, gib-fixers, sprinkler installers. Even the guy who sweeps the floor — it’s really hard to get a motivated site labourer.”

Todd says there’s a lack of investment in training, plant and equipment, and research and development, which creates a vicious cycle. “People on site are unproductive because they don’t really know what they are doing because they are not well trained,” he says. He also thinks it’s important to attract people back into the sector by raising wages. While a lot of basic sub-trade costs such as gib-fixing, bricklaying and painting have escalated by 50 per cent over a three-year period, the person at the end of the paintbrush or fixing the gib or laying the bricks isn’t getting 50 per cent more wages. “It’s going to the management-owner level — the guy who is running the crew of 20 painters, bricklayers or tilers. That escalation in construction cost isn’t actually helping the worker.”

As he has said before: the housing sector is just a prism through which you see the neglect.