May 16, 2019 Property

An iconic mid-century Auckland social housing block is to be razed rather than refurbished. Does it have to be this way?

This story was originally published on Homes to Love and is shared with permission.

The iconic mid-century Auckland social housing block being demolished

They wanted to sanitise a place they labelled a slum, but ended up slowly re-creating one. Early last century, Auckland’s Grey Street (later renamed Greys Avenue) was the heart of a bustling Chinese quarter, a place that caused authorities to fret about prostitutes, gamblers and opium dens. Their motives were likely tinged with racism – a Chinese neighbourhood in the central city wasn’t universally regarded as desirable – but the city council and the Labour government of the time nevertheless decided to tidy it all up.

Their ambitions were enormous: Julia Gatley’s book Long Live the Modern describes how the initial plan was to acquire and raze every property on the street and erect more than 450 flats in their place. By the late 1940s, a rise in building costs meant they settled for erecting four blocks containing a total of 50 units on the western side of the boulevard instead. These buildings were designed in sleek European modernist style by architects at the Housing Division of the Ministry of Works under the leadership of Gordon Wilson. They are now classified as a Category Two Historic Place.

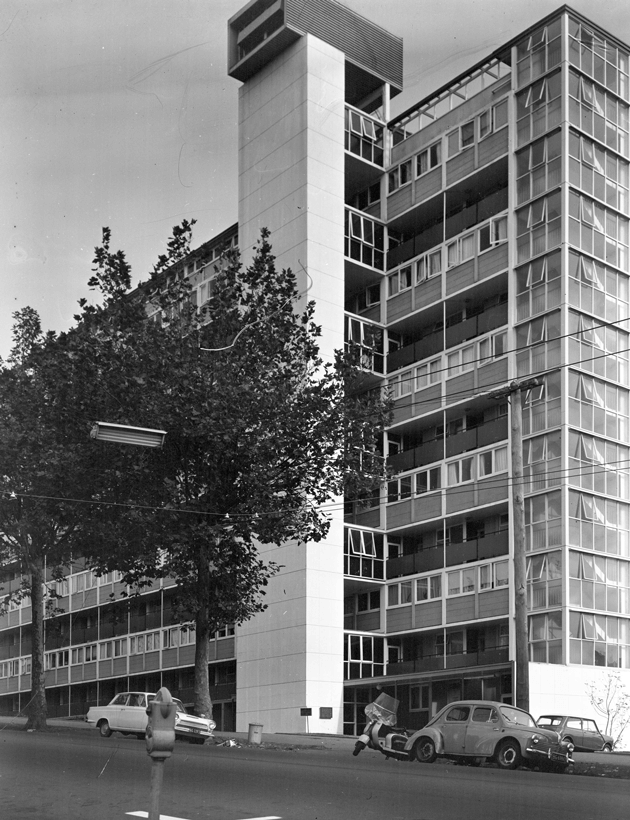

Less than a decade later, Wilson and his team again turned their attention to Greys Avenue, this time up the hill on the southern end of the street. They designed a slender nine-floor building containing 86 flats, most of them compact two-storey ‘maisonettes’ with two bedrooms and a bathroom above a simple living area and kitchen. Completed in 1958, the Upper Greys Avenue Flats were for lower- or middle-income singletons or couples who desired a life in the city.

The building presents a slab-like face lined with walkways to the street, while the northern elevation, with its intricate arrangements of windows and little inset balconies, has a more human scale. A separate lift tower adds a dramatic flourish. The building is a beautifully monumental piece of architecture, social housing on a scale that this country hasn’t seen since. But there’s a problem. Housing New Zealand, which owns and manages the building, now plans to demolish it.

In some ways, it’s not hard to see why. I visited the flats in mid-April with Housing New Zealand’s regional manager Neil Adams, advisor Scott Foley, and communications advisor Sarcha Hayter. The building still has great bones, but looks tired and neglected. Foley gave us a depressing health and safety briefing in the Housing New Zealand office on the ground floor, where a security guard is stationed outside and banks of monitors relay feeds from cameras all over the building. We were told to watch out for objects like shopping carts falling from the open-air walkways, and to be wary of residents who might become distressed or aggressive if they saw us.

In recent years, police have sometimes been called to the building more than 60 times a month, although new security measures such as a fence around the property have reduced this number. There has been a machete attack (the person who was attacked survived). Another person was injured after jumping from a balcony when being threatened by someone else in the building. The original architects probably didn’t anticipate any of this. The flats, Adams says, “weren’t designed for this level of complexity”.

Housing New Zealand now wants to demolish the building to erect something bigger: a brand-new development with 250 to 300 apartments, three times the number the current building holds. But it isn’t just the size that matters. Adams and Foley say the current flats are no longer fit for purpose. The two-level units aren’t suitable for aging tenants who find it difficult to climb the stairs from the living area every time they need to use the bathroom. The long open-air walkways that connect the apartments on each floor mean the influence of disruptive tenants spreads quickly, making some residents afraid of leaving their homes. The two-bedroom configuration of most of the flats can be problematic: some tenants who moved to Greys Avenue to escape toxic living environments are pressured by friends and family members to allow them to use their spare bedrooms, which means the problems they are trying to leave behind follow them to their new homes.

These issues aren’t unique to this building. Modernist housing blocks like it have had terrible global press, but it’s too simplistic to say their design is soley responsible for the ills that have befallen them. Yes, many of them had insufficient consideration for the varied needs of the residents who would occupy them. But many of them were also poorly managed. Rather than creating mixed communities for residents from different backgrounds and income levels, these buildings often became isolated monocultures. People were given poorly maintained apartments, insufficient social support and, in many cases, inadequate educational or employment opportunities. The results of this neglect – of an austere, short-sighted approach to social welfare – are abundantly evident in Upper Greys Avenue today.

Adams and Foley say the new building that’s been planned for Greys Avenue, for which renderings aren’t yet available, will follow best practice internationally. It will be designed by Mode, an Australian firm with offices in Vietnam, India and Auckland. It will house a variety of Housing New Zealand tenants – old and young, high-needs and independent. (Housing New Zealand has been consulting current residents about rehousing them while construction of the new building takes place). Support services such as a medical clinic and other facilities will be located on site. The new units will mean an existing partnership with Housing First, a successful pilot programme which rehouses homeless people and provides them with wraparound support services, can be expanded.

It’s important to remember that restoring the building wouldn’t be an impossible task. The Lower Greys Avenue Flats and Wellington’s Centennial Flats in Berhampore (1939-40, now a Category One Historic Place, and also designed by Gordon Wilson’s team) have been successfully renovated in recent years for Housing New Zealand tenants. Collectively, these buildings reveal a history of medium-density social housing in this country, an important counterpoint to the dominant cottage-in-a-garden narrative of the stand-alone state house.

But the Upper Greys Avenue Flats are that awkward age where they haven’t been granted heritage protection. The way the building is sited offers few opportunities to densify around it without compromising light, sun and access to the existing flats. And now Auckland’s acute housing crisis means trying to save the building looks like bourgeois indulgence. It could be gentrified, for example, with refurbished apartments sold at market rates. But this would be an expensive exercise for a private developer, and insisting on the retention of the building would depress the value of the site if Housing New Zealand chose to sell it, diminishing the number of new homes the organisation could create elsewhere. The flats could be renovated to contain a mix of market rate and social housing units, but this still means losing the opportunity a new building offers to provide much more accommodation for people in need.

Which brings us to an uncomfortable either/or situation: arguing for the retention of an architecturally important building means you are standing in the way of the provision of more social housing, which is something I would never want to do. So I find myself reluctantly assenting to the demolition of a building that feels like an old friend, a structure I appreciate every time I walk by. I wish we were a culture that embraced more nuance; that we were able to avoid the stupidity of constantly forcing ourselves into these needlessly binary situations. Above all, I hope we’ve learned from history, and that these contemporary clean-slate aspirations don’t result in the same mistakes our predecessors made. The last thing we want is to create yet another mess for future generations to clean up.