Nov 2, 2015 Property

This article was first published in the October 2015 issue of Metro. Illustration: Lauren Marriott.

Watch how this illustration was created.

“The Auckland property market is on fire,” says Finance Minister Bill English, “and some people are going to get burned.” How about we put out the fire? Here’s a plan.

One million dollars! Bwahaha. At the rate we’re going now, the average sale price for a property in Auckland will reach one million dollars early next winter. Less than a year from now.

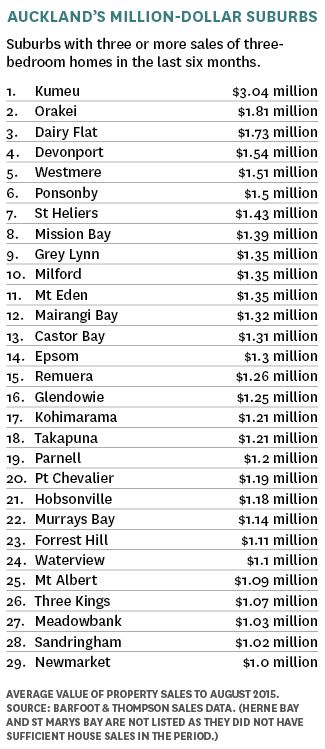

Whatever your stake in the property market — investor, homeowner, renter, desperate would-be homeowner, speculator — the statistics are now Officially A Worry. Auckland prices rose 20.4 per cent in the year to August and the early part of 2015 was “an almost frenzy-like madness”, according to John Bolton of mortgage brokers Squirrel. Over the past 30 years, the cumulative increase has been 1500 per cent.

Horrifying if you’re trying to buy your first home? You bet. But good if you have money to invest? Not necessarily. The market slowed drastically in July. Sales agency Barfoot & Thompson, with about a third share of all house sales in the city, actually had lower prices that month than in June and May, and in August they dropped another 1 per cent.

Everyone was expecting prices to start rising again with spring, but if you thought the property market was a sure thing, take note that in 2015 it has become more volatile. Both Finance Minister Bill English and Prime Minister John Key have warned of risky times ahead, and they are not alone.

It’s not a New Zealand thing or an Auckland thing. Our prices have risen, on the whole, for reasons that have driven up property values in cities all over the developed world. “Asset markets globally (including real estate) will at some point see a correction,” says Bolton. “Yes, some people will get burned.”

Barfoot & Thompson boss Peter Thompson thinks we are “at a crossroads”. Economist Shamubeel Eaqub told North & South magazine in April that “you can’t have prices going in one direction forever; you’ll run out of fools to buy houses”.

There’s a bit of that, perhaps. But the Chinese economy is falling on its face and dairy prices have slumped. So have oil prices. The government, Auckland Council, Reserve Bank and even some lending institutions are all keen to see the market slow.

Quotable Value reckons the biggest influence on the market is consumer confidence. “That confidence has taken a knock in recent weeks,” QV reported last month. “There are increasing dark clouds on the global economic horizon which sooner or later people are going to start paying serious attention to… Although the New Zealand economy is still more resilient than most, a really serious shock would certainly hit us hard.”

More extraordinary figures… If you live in an average house, last year it earned more than $3000 a week. For most households, that’s more than the combined incomes of everyone living there.

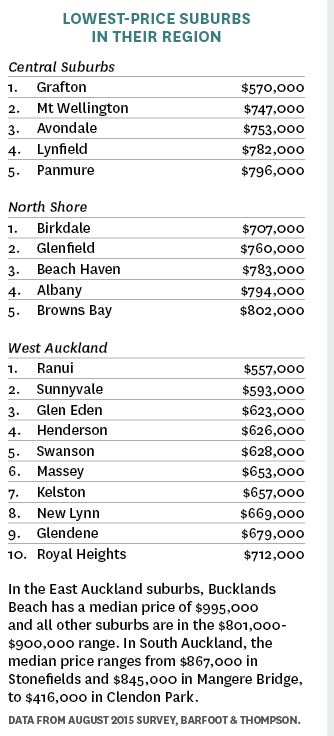

At $875,000, an average home in Auckland now costs 10 times the combined average annual income of a couple in their 30s. Nationally, the ratio is half that.

Auckland’s population growth is strong and fuelled largely by migration (that’s New Zealanders shifting here from other parts of the country as well as immigrants). Long-term predictions are notoriously difficult, so let’s use a short-term one: by 2023, just eight years from now, Auckland will have grown by the size of Hamilton.

How do we get an end to rampant house price rises, without it being achieved by a crash? Here’s our 10-point plan.

1. Fix the lending rules

You don’t hear this often: the Auckland property boom has not been driven by a shortage of supply. As in, a shortage of houses for people to live in. It’s been driven by investors. There is a shortage of houses for people wanting to buy their second, third, fifth, tenth properties.

As most people who’ve been to auctions know, residential property is disproportionately snapped up by investors with the financial resources to outbid prospective homeowners. This has severely distorted the property market: while 54.5 per cent of homes nationwide are occupied by their owners, in Auckland the figure is just 41.7 per cent.

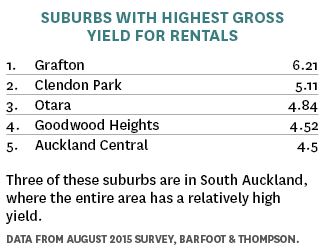

The fact there is no major shortage of homes for people to live in can be seen in the fact that rents are not rising. Irony of ironies, while Auckland property looks like a hot investment, there has been little growth in rental prices since January. The attraction is the capital gain.

Quotable Value reported in September on “high levels of speculation in the Auckland market”, noting that “more than 2000 homes have been bought and sold more than once over the past 12 months”. QV added, “Often nothing has been done to improve these properties at all and speculators are just on-selling and taking the capital gain.”

What’s caused the disproportionate influence of investors? Short answer: there’s too much money available to them.

Banks are allowed to treat home loans as low risk, so they can hold smaller reserves to cover mortgage lending than they must for other loans, such as those given to businesses. This low “risk weighting” means they have more money to lend and more incentive to lend it on property, and it also makes it easier for investors to borrow to buy property.

Earlier this year, the Reserve Bank proposed that investors owning five houses or more should be treated as small business owners — with their loans treated as corporate property loans and their income taxed accordingly. The banks beat them back.

Belatedly, but more successfully, the Reserve Bank will introduce new loan-to-value ratio (LVR) rules on October 1, specifically for investors in the Auckland market. They will now need to have 30 per cent of the value of a property they wish to buy in order to borrow the rest from a bank.

“The objective of this policy,” announced the bank’s governor, Graeme Wheeler, “is to promote financial stability by reducing the rate of increase in Auckland house prices, and to improve the resilience of the banking system to a potential downturn in the Auckland housing market”.

“The objective of this policy,” announced the bank’s governor, Graeme Wheeler, “is to promote financial stability by reducing the rate of increase in Auckland house prices, and to improve the resilience of the banking system to a potential downturn in the Auckland housing market”.

John Bolton at Squirrel thinks the 30 per cent deposit rule will have “a larger impact than most people realise”. We hope he’s right.

Directly aligning risk weighting with business loans has been proposed by commentator Gareth Morgan, and internationally the issue has frequently been taken up by the Economist and others. There are signs of change. Australia, for example, is raising the risk weightings on mortgage lending for the big four banks.

New Zealand should reform the risk weighting for property investment.

2. Fix the tax rules

It’s pretty obvious the big goal should be to create a genuinely level playing field for investment. If you earn income from a capital gain on property, why should it not be taxed in line with other income?

The answers to that are usually pragmatic and expedient. A capital gains tax (CGT), it is argued, would not help resolve market distortions, especially because it would almost certainly exclude family homes. Perhaps more to the point, voters would not support it.

But because property’s capital gains potential has largely been ignored by the tax system, it has an unfair advantage among investments, and that has distorted not just the property market but the economy as a whole. It diverts money that would otherwise go to more productive sectors.

To a degree, the government has accepted this. The new Taxation (Bright-line Test for Residential Land) Bill, now before a select committee, proposes to tax as income any gains from residential property bought and sold within two years. It’s not a CGT, but it is, a bit. Revenue Minister Todd McClay says the bill will “make it easier for Inland Revenue to identify speculators in residential property and make sure they pay their fair share of tax”.

That’s great to hear: a minister endorsing the principle of everyone paying their fair share of tax.

The Bright-line Bill should be the start, not the end, of tax reform related to capital gains. It will need cross-party agreement to succeed.

3. Investigate the cost of building

It costs $1787 per square metre to build a small house of 145m² in Auckland. At $1627 per square metre, a large one (202m²) doesn’t cost much less. It’s far too much.

According to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), building costs in New Zealand are 30 per cent higher than in Australia, and higher again than in the United States.

Housing Minister Nick Smith knows about this and has called for more transparency over costs. Fletcher Building and Carter Holt Harvey know about it, too: they had a cosy deal to fix the price of framing timber, until Fletchers dobbed Carters in to the Commerce Commission. Last year, Carters was slapped with a $1.83 million fine.

The Productivity Commission also knows about it: building costs, it says, are one of the key drivers of inflated property prices.

Enough with the hand wringing. We need a commission of inquiry into the cost of building materials and practices.

4. Reform the planning approvals processes

The government and council are two years into the three-year term of a Special Housing Accord. Its purpose is to identify special housing areas (SHAs) and encourage construction in them, especially by speeding up the planning approvals process.

To support this, the council has a “one-stop shop” for planning, advice and consent applications in the SHAs, called the Housing Project Office (which will shortly be merged with the council’s City Transformation Unit).

To date, the minister has approved 97 SHAs under the Housing Accord, and the council has another 41 ready to recommend. On both sides, they say they’re happy with progress. They shouldn’t be.

Building consents for the whole of Auckland have risen to around 8500 a year. That’s still well behind the official target for the accord of 39,000, or 13,000 a year.

What’s slowing up the process? Two things.

The first is the Resource Management Act (RMA), which the government, Productivity Commission and many developers say stifles growth. But because Labour, the Greens, New Zealand First and the Maori Party all oppose the government’s plans to reform the RMA, they are stalled. RMA reform was probably the biggest single casualty of the government’s loss of the Northland electorate to Winston Peters in the byelection this year.

The stalemate is unfortunate, because the RMA does need updating. Not because it’s a bad law: its requirement that environmental planning be integrated with economic planning is very sound. New Zealand is a vastly better place for the planning regime the RMA has guided since 1987, and opponents of the government’s plans for drastic reform are right to worry.

Nevertheless, the RMA could be improved. In a range of relatively minor matters, compliance can be cumbersome and expensive. The RMA enables a kind of obstructive mindset among council officials throughout the land, and particularly in Auckland. Those things can also be true for the appeals processes.

Yet the government now seems less interested in RMA reform than in political points-scoring about it.

No more pleas of impotence. The government should work with other parties to find a constructive way forward.

The second factor slowing things up is that Auckland’s new rules as set out in the Unitary Plan (UP) include some speedier processes, but they’re on hold while an independent panel considers public submissions. The panel will report back in July next year, the council will be asked to approve the UP in September, and then we’ll have a council election and all bets could be off again.

5. Thicken the middle ring

You think Los Angeles is a sprawling city? It sure looks like it: very little high rise away from the CBD, and endless suburbs stretched across the plain and into the hills. Here’s a surprising fact: Auckland, like Melbourne, is about half as dense as Los Angeles.

We could double the capacity of the city within its existing limits and you would notice little change to the scale and closeness of the suburban environment. As Eaqub told North & South, “We know that if we allow a little bit of height, we can accommodate most of the increase predicted for Auckland within the existing blueprint.”

This isn’t a matter of ideology or lifestyle preference — or it shouldn’t be. Having more people living closer to the centre has sound practical value.

A generation ago, it made a lot of sense for many people to live in South Auckland because their workplaces were also there. The factories and warehouses of the south were at the heart of the city’s economy. But most people now work in service industries, not manufacturing, and service jobs tend to cluster in the city centre. The city is not what it was.

It makes good sense to live reasonably close to your place of work. You don’t have to live above the shop, but for most of us, whatever work we do, a short commute translates directly into a better quality of life.

Right now, this growth is not a particular problem for Auckland: apartments are the fast-growing sector, and they’re almost all in the centre, or along transport links like Great North Rd, or in the growing town centres like Albany and New Lynn.

But as was cogently argued in Auckland recently by John Daley, CEO of the Melbourne-based planning consultancy the Grattan Institute, we also need to thicken the “middle ring”.

That’s the broad band of suburbs that runs roughly around the western edge of the Tamaki Inlet and along the northern boundary of the Manukau Harbour, up through Henderson and Te Atatu, over to Glenfield and across to the East Coast Bays.

Daley looked at the situation of a retired couple living in their family home and hoping to see their grandchildren quite a bit. The grandparents live in the middle ring or perhaps closer — in Remuera or Devonport, say. They’re deeply connected to their suburb and don’t want to leave. But their kids, the parents of the grandchildren, can’t afford to live nearby. They’re being forced to buy somewhere far closer to the rural boundary than the middle of town.

Boil that down. The grandparents need smaller homes in their suburb they can move into; the rest of the family needs relatively affordable housing that’s less than half an hour away. The solution? Not for everyone (but no single solution is for everyone): a lot more townhouses and apartments.

Not developed randomly, and not so they block all the sun and views. Built with both care and commitment, in three different ways:

• New, intensive, ground-up precincts in brownfields developments, such as the quarry at Three Kings.

• Apartment blocks around town centres and along transport corridors, in areas that are currently poorly used.

• A lot more two-storey and three-storey blocks, sprinkled through the inner and middle rings.

These things are happening now, but slowly. The council has prioritised brownfields developments, although the government hasn’t backed the approach, and as the council’s growth and infrastructure strategy manager, David Clelland, commented recently, most major development proposals relate to greenfields, not brownfields sites. Too many developers are still more interested in building out than up.

Why is middle ring growth so slow? Principally, because of nimbyism. Even when we agree with “density done well” in principle, we still don’t often agree with it in our street.

There’s something else about this approach: it fits larger social goals. Daley says, “Middle-ring medium-density development is probably the largest single lever for both economic growth and social equality.” People are more productive when they are not driving all the time. Society feels fairer when different types of housing are mixed together.

Compounding the problem is the impasse between government and council over their conflicting visions for the city. The government gets excited about greenfields developments on the urban fringe and is not so keen on intense growth along transport corridors and in brownfields areas closer to the centre. This impasse is a travesty of the original intent of the Super City.

The council needs to make much more of showcase developments that prove density can be done well.

The government should give much more active backing to brownfields developments within existing urban areas.

6. Commit to affordable housing

Those 97 special housing zones established under the Housing Accord are for all kinds of housing, and often the component of “affordable housing” is very small. Significant growth in the number of affordable homes will involve:

• Greater political commitment to getting them built.

• Help for builders wishing to scale up their operations. New Zealand has a lot of small builders and some big construction companies, but we don’t have enough companies in the middle: firms with the financial resources, breadth of skills and systems expertise to build subdivisions and housing complexes.

• Help for building technology innovators. Prefabrication — the mass production of off-site construction components — has been a factor in this country since the middle of last century, but in recent years only a few companies have applied the technology to the residential sector.

• Inspirational thinking from architects, urban designers, technologists and everyone else who fancies they could come up with new ways to build stuff. And help for that thinking.

How about some incentive schemes: to upscale builders; to support technology innovators; to reward designers who can come up with modular but characterful, cheap and gorgeously attractive, energy-efficient building projects to house 1000 people at a time for $900 per square metre — half what it costs now?

7. Treat vested interests for what they are

Banks and real estate agents are asked to comment on the property market all the time. And sure, they’re experts and they have things to say. But despite their best efforts to appear above the fray, neither group is independent. Banks have customers to look after and money to make. Agencies have the interests of their clients — the vendors, who usually want the highest possible price — front and centre.

Banks and agencies should be treated as partisans, not impartial observers.

8. Overhaul education and trade training.

Education is focused on getting young people to the tertiary level: university or trade training. But there’s a reality gap. While we continue to produce far more lawyers, PR “executives” and graphic designers than we need, we are, remarkably, still producing too few tradies for the construction industry.

Carpenters, bricklayers, cabinet makers, plumbers and electricians are all among the 15 trades with the biggest skill shortages in New Zealand.

Training programmes for builders and related trades should be accelerated.

9. Tighten property ownership rules

The government’s decision to decline the bid by Shanghai Pengxin to buy Lochinver Station near Taupo was remarkable for being so unusual. New Zealand is one of the easiest countries in the world in which overseas investors can buy property.

It’s not clear what the impact of this is on house sales in Auckland. But it is clear, as John Bolton at Squirrel says, that many recent immigrants “can access large amounts of capital from offshore”. In light of this, the Australian approach doesn’t seem unreasonable: overseas investors are welcome, but the housing stock they buy must be new. Everybody benefits from the economic activity that generates.

And it is absurd that we have bitter arguments about foreign ownership without knowing the facts. The government has introduced new rules to help with this. From October 1, overseas buyers will be required to provide taxation details for all property contracts, and on April 1 next year, this will apply historically. That’s going to allow a register of ownership to be created, although it’s still not clear how public the data will be.

We need rules for overseas investment and reporting here that help to grow the economy and facilitate well-informed debates about demographic and investment trends of all kinds.

10. Commit to the regions

10. Commit to the regions

It’s not easy to tell people who want to live in Auckland that they should go somewhere else instead. But New Zealand does need more people, proportionately, to live beyond the Bombay Hills. So why is so little being done to bolster the regions’ future?

It’s not necessarily a matter of picking winners among various industries or businesses. But there is a major infrastructure deficit. We have no national freight and transport policy, no plan to revitalise the railways and underwhelming commitments to broadband.

Transport planning actually appears to be killing the towns: take a drive through the Waikato and look at how the new bypasses will keep traffic, and the economic life they bring, away from the towns. Ngaruawahia has already gone: are we ready for Huntly, Tirau, Putaruru and possibly even Cambridge to die as well?

We need a forward-looking regional economic strategy, for the benefit of the regions and also to help take the pressure off Auckland.