Feb 3, 2025 etc

6.17am: Sunrise

Charlotte Muru-Lanning

In this city, many are already awake — some at work, some on their way, others just wrapping up their shifts. I’m not usually among them, but today the sunrise calls. Though it is still dark, on Tāmaki Drive the street lights begin flickering off in domino-like succession, anticipating that their job will soon be taken over by the sun. I turn off toward Bastion Point, following a Fulton Hogan truck up the drive — I’m not sure what kind of truck, perhaps they’re doing maintenance. We both park, the only two vehicles here. To the east, where the sun will soon usher in a new day, Berkeley Cinema’s red and green lights glow against an otherwise inky Mission Bay.

I think of the significance of the ground I’m standing on. An annoyingly low-resolution black and white photo I have saved on my laptop comes to mind: my great-grandfather, a Pākehā man, standing here, or hereabouts, in 1977, among a crowd of protestors, Dame Whina Cooper and Joe Hawke at the front. “He is the gentleman standing behind the kuia pointing to her left,” reads the Facebook message my great-aunt sent me along with the photo. “He was among the first arrested and charged.”

At 6.20am, the sun finds its way above the clouds. And just like that, birds break into song. Hinewai appears, as does Uenuku, a rainbow framing the city behind me. It seems too perfect that a rainbow would appear at this moment, so I attempt to take a picture as proof.

Returning to my car, I feel a pang of self-consciousness, like you do when you’re a teenager. The whole world is watching you with judgemental eyes. I wonder what the workers in the truck think of this woman in clothing that’s weirdly formal for a park, let alone at this time of day, velvet ballet flats soaked, frolicking around with a notebook and disposable camera. I needn’t have worried — they’re both in their seats, fast asleep, the sunrise streaming through their windshield.

6.45am: Auckland Fish Markets, Wynyard Quarter

Charlotte Muru-Lanning

They came, they bought fish, and they were gone — all before dawn. Ordinarily, 30 to 35 bidders would fill the room from 6am sharp, but today there were just 25, Jorge Mondragon tells me. He’s been here since 5am, though other workers began to receive fish even earlier, during the overnight delivery window — 10pm to 5am.

When I see the auction room I’m caught off guard: it’s so utilitarian and starkly functional that I gasp quietly, which draws a quizzical glance from my ‘guide’. Rows of green and white desks, all empty now, are laid out like a lecture hall. I feel a bit gloomy not to have seen the buzz of retailers, fish-and-chip-shop owners, restaurateurs, chefs, wholesalers, caterers and supermarket buyers, all tapping their bids into the built-in keypads on the desks. The main screen, which displays fish prices by the kilo when bidding starts, is now playing CNN.

While the rest of the public-facing fish market has been refurbished with a polished, faux-nautical facade, it’s a bit of a relief to encounter this auction room that feels so decidedly last-century and extraordinarily uncontrived. A holdover from a different era, a little frayed, charmingly out of date. Framed maps and photos of various boats line the walls, genuinely faded by time.

7.31am: Jervois Steakhouse, Ponsonby

Rohan Botica

The ROC Build boys pull up to the site and start unloading a trailer. Jervois Steakhouse is getting a facelift. Bossman JJ has been awake since 4am thinking about work. Bas is trying to get his hours up after a trip overseas with the Samoan rugby team. DK arrives once he’s dropped his kids to kindy.

The boys travel from Avondale anywhere in the city to do renovations, and Avondale comes with them. The Makita radio fires up ‘Dilemma’ by Nelly, ft. Kelly Rowland. Ponsonby’s pedestrians are getting a free 2000s R&B concert today. JJ’s grandmother Lesieli used to live right behind this spot. The neighbourhood has changed a bit since then.

Times are tough. The best recession indicator is how many days before payday the ute fuel light comes on. But the guys pride themselves on work ethic and grinding things out. Don’t get caught standing around. Don’t ask a question unless you’ve already considered solutions. Use your initiative. Prepare ahead to make the next step easier.

“What do you think about to help you when mahi gets hard?” I ask. Bas replies, “The end result. The finished product. You have to see it through.” For DK, “My ‘why’ is my kids. I feel the responsibility to get up and provide,” he pauses, “and to not be a lazy ****.” The seriousness vanishes and we crack up laughing.

8am: Flava Breakfast with Stace, Azura & Charlie studio, central city

Taualofa Totua

The studio at Flava, the radio station of ‘classic’ hip hop and RnB, observes the daily commotion of our city, wide awake and moving this morning. It’s a corner room with glass on all sides; an internal window faces the comings and goings of the building, home to media conglomerate NZME. Sound waves travel outside to listeners, carrying chatter about trick or treating, cringe parents and their inappropriate comments, and the concert of rap artist Travis Scott tonight. I imagine the range of them, the thousands — some sitting in traffic, others shifting heavy loads or out for a run.

Steadily, with buttons clicking and tracks switching, four cogs in this wheel keep the breakfast show turning: producer Anna Shine, fresh out of broadcasting school, and hosts Stacey Morrison (broadcaster and te reo advocate), Charlie Pome‘e (broadcaster and musician) and Azura Lane (broadcaster and presenter).

Flava’s morning slot is more music focused than other morning shows are, but the hosts still highlight their expertise and energetic storytelling while chatting between songs. I cast my eye over the schedules and tables of preparation on the multiple screens that Shine oversees. “We don’t script our shows, but there is a lot of planning involved,” she tells me. During a quick five-minute break, Pome‘e and Lane, who are both on a fitness challenge, reveal their meal-prepped breakfasts to me — variations on oats. Nesian Mystik plays in the background.

8.05am: J. Love Cafe, central city

Charlotte Muru-Lanning

I’m on the ground floor of a pink 1980s office building where Chang Lee and Jessica Jung have been running this weekday-only coffee shop for the past two and a half years. Today, the doors opened at 7am for the steady stream of customers trickling in; mostly for to-go coffees, but occasionally for a scone, too. “Cappuccino?” Jung calls out knowingly, as a regular approaches the counter. As jazz hums in the background I wonder if the ‘J’ in the shop’s name might stand for ‘jazz’, or perhaps ‘just’. Jung clarifies: “The J is for Jesus, because Jesus is love.”

8.30am: Smales Farm, Takapuna

Hayden Donnell

Inside the Smales Farm bus station, an elderly woman sits on a bench watching a group of high school students. It’s hard to follow what they’re talking about, but it seems to be potato chips. “PO-tay-TO,” says one, to no one in particular. “He said the mug photo of me was good,” adds another, beguilingly. Buses park up, but the older woman doesn’t make a move. This show’s scripting may need some work, but it’s better than whatever’s on TV at 8.30 in the morning.

During rush hour, buses arrive every minute or so, pulling in off the Northern Busway on their way north to Albany or south to the city centre. It’s a bustling intersection of disparate lives. Men in jeans and dress shirts disgorge from the NX1s and trudge toward the One NZ building in the nearby office park, slurping cans of blue V. Pupils from Westlake Boys and Girls high schools hang about with glazed eyes, taking advantage of the $3.50 student special on drinks at the station’s coffee cart.

There’s a kind of peace in the busyness. The people here move like they’re being pulled on a string, guided along the well-worn paths of routine. Hundreds of them pass each other every minute, a mess of stories briefly entwined by the city’s only truly efficient rapid transit service.

A loud noise pierces the low murmur of passing commuters just before 9am. A bald guy in blue board shorts is remonstrating with an employee at an AT help desk. “Your system doesn’t work online,” he yells. “Fix it.” The employee doesn’t raise his voice. He tries to calm him down. But the man isn’t having it. He points angrily and stalks off. Afterward I head over to ask the worker if he’s fine. “Oh yeah, thanks for asking,” he says. “It happens quite a bit. You get all types here.”

8.45am: Breakfast at Auckland City Mission Te Tāpui Atawhai, central city

Charlotte Muru-Lanning

On the ground floor of the City Mission’s 11-storey HomeGround building on Hobson St, the dining room is abuzz with the energy of a well-oiled neighbourhood cafe — only here, food is served canteen-style from silver bains-marie. Diners move down the line, chatting and building their meal as they go, contemplating and then choosing from an eclectic mix of roast pork, fries, toast, porridge, fruit, jelly, even Little Island banoffee ice cream (yes, ice cream for breakfast — yum), all dished up by volunteers behind the counter. Once their selections are made, they cart their trays off to tables scattered throughout the room.

Haeata Meal Service is a free breakfast service, open to the community, that runs from 8am to 11am every single day of the year. For many attendees, it’s become part of their morning routine — a welcoming space where people can find a warm meal, a comfy place to be, and vital services like medical and pharmaceutical care. Since the meal service began two and a half years ago, demand has steadily increased. Haeata once fluctuated between serving 170 to 350 meals a day, and now consistently serves up to 350, with no signs of slowing. We talk a lot (but perhaps not enough) about food insecurity in this country — the ugly disparity between our abundant food production and the many who struggle to secure their next meal. When you’re someone experiencing homelessness, achieving food security is virtually impossible.

Today in the kitchen there are seven apron-wearing volunteers, who have been here since 7am. They’re in full throttle — greeting diners, conversing with regulars, dishing up meals, preparing more food and clearing plates. It’s a scene that feels lively, cheerful and familiar. As service ticks along, the line in front of the food trays seems ceaseless, perhaps even growing longer.

Directing it all is Svetlana Pogoda, the full-time kitchen manager, hair tied back into a slick ponytail, with crisp chef whites on. She takes a brief break from prepping a glass noodle salad, soon to be added to the brunch options. The kitchen operates on a tight budget, and since the mission is not government-funded it relies heavily on food and monetary donations from the community. Svetlana talks in a brisk, no-nonsense way about the challenges, but seems driven by a singular goal: “I want my food to give people a little bit of joy, a little bit of pleasure — if that’s your one meal for the day, make it a good one.” There’s a specific cadence to the weekly menu, she says. “People love sweets”, so there’s always a dessert of some form; scrambled eggs are traditional on Saturdays; there was mince on toast on Monday. Today, Svetlana has a glut of eggs, so tomorrow it’ll be egg pies.

8.55am: Central City Library, central city

Sam Brooks

There are 13 people, myself included, outside the Auckland Central City Library before it opens at 9am. Nobody is there with another person. None of us, at a glance, have anything in common other than that we all want to be at this particular library at opening time. We are as conspicuously diverse as a photo in a university catalogue.

The art gallery clock rings slightly early, as though getting a jump on the day. Not long after, the library doors open and all 13 of us amble in. I’m familiar with this library’s layout — holds and an activity area on the ground floor, books and computers on the second, archives and exhibition space on the third — but I’ve never actually spent much time in it.

A few people move straight upstairs to the computers; others to the shelves; others to particular spots to set up what I can only assume are their workstations for the day. After I find my own spot, and a book to read (actually, a play — The Hills of California by Jez Butterworth), I’m immediately aware of the library filling up. I always associate libraries with silence, but that’s not quite right. Libraries are not silent, they’re quiet. Quiet is its own thing; it’s the potential to make noise and a shared agreement not to.

The noises of the library are mostly subtle ones: someone tapping away on a laptop, a request to use a power point, the cap of a water bottle being taken off. A bag of chips opens near me, and it might as well be a gun going off. The quiet of the library is a fragile one.

Mere minutes after settling in, I remember what the appeal of a library is. Libraries around the world differ, obviously, but they operate on a shared social contract: the appreciation of anonymous quiet, sheltered from the world, yet full of its knowledge. It being 9.01am at the library is functionally no different to 4.59pm at the library. As long as the library is open, it is both hoard and refuge.

When I leave, I hear an old man with an unidentifiable accent asking for directions to Britomart. That’s the third thing a library is, regardless of its location, regardless of the hour: a place where you can ask for information — and receive help.

9.33am: Undisclosed West Auckland GP clinic

Miriama Aoke

Thanks to the rain — the New Zealand mould kind, not the nice relief-in-the-tropics kind — it smells like damp bitumen, along with some wafting lolly-scented vapes. There’s a slew of foot traffic, and people are emerging from the clinic in pairs, about half wearing masks. A man with grey hair, past shoulder length, wearing high-vis shoes and tube socks, stops on his bike under the cover of the clinic for respite from the rain. There are constant drop-offs, but the rules of the loading zone (is it a loading zone? or is it timed? can we park here?) confuses everyone. The secret is that it is neither. You are either lucky or unlucky. I got a ticket here once.

What sounds like a smoker’s cough draws my attention. It’s coming from a small girl and her mother as they duck and run to their car. Two kids from a local high school, sans umbrellas, are unfazed by the weather, and make their way to the bus stop. A brainy woman in double denim carries a floral umbrella and sort of bounces in contempt of us idiots who didn’t plan ahead. A mum and her daughter emerge; both have umbrellas, but they’re not rubbing it in anyone’s faces.

9.43am: A man in a red and black tracksuit is approaching. He is heard before he is seen, singing nonsense on purpose to unsettle the rest of us. A woman carrying a Balenciaga tote and her poor feet in heels, with extensions that are sadly visible, trots to the pharmacy. Someone — I see, now that I’m surveying the pharmacy more closely — has muddled the sign out front, escaping the notice or care of staff. The sign reads EAR PIE CING. There is a woman with shiny blonde hair, enviable on a really wet day (how does it stay like that?), wearing all black. God called for balance, so her feet are soaked because she is wearing sandals. Why are we not better prepared, Tāmaki? We know how this goes. I look at the ground, because if I look at faces people do that funny thing and pretend I am invisible. Health feels sensitive. Health is sensitive! There is nothing innocuous about this red JOTTER PAD.

9.53am: Someone is getting out of the taxi. This kuia, known to the taxi driver, exits. She is here to pick up or fill a script. The taxi driver grabs her walker from the boot and locks it in place and, mask on, our kuia glides on to the footpath and disappears into the pharmacy. The sun now makes an appearance, as have a few pairs of shorts. The man on the bike has re-emerged. If it was motorised he would be revving. He sits, pausing, on the corner — swinging his head, watching the jolts of traffic, trying to avoid collision at the intersection. Music decorates empty time from cars passing. ‘Come As You Are’, Nirvana, blaring from a two-door, rounded Mercedes. The driver leaves his dog whimpering in the front seat. A wiry foxie. The man walks into the pharmacy. He looks like Ben from Shortland Street (it’s not him). The Waipareira Trust van is also here, swathed in imagery from their award-winning ‘Proud to be Māori’ campaign, but I pray it is not an interactive thing.

10.02am: The Mercedes driver has what he needs, and is leaving. The V8 engine is driving him, not the other way around. Is he as full of himself as I have assessed him to be? We are all unreliable narrators.

10.24am: Prochem Pharmacy, Avondale

Rohan Botica

At the pharmacy in the heart of the Avondale shops, things are quiet. A woman approaches the counter. Azaz Member and Mahvish Iqbal already know her name. That’s what they tell me their job is. Yes, to explain and provide medicine to customers, but really to get to know them — to build rapport. People are isolated these days, especially the elderly. They cherish this social interaction.

There are massive apartment developments nearby. Burnt Butter Diner across the street is getting rave reviews among the Instagram brunch community. The area is growing. More people to get to know.

I ask Azaz about the signage outside — “STOP THE KILLING OF CHILDREN”. I had assumed it was an uncontroversial message. It turns out the sign had gone viral and drawn backlash abroad. “Most people around here are supportive, they encourage us to use our voice.” And the critics? Azaz cuts me off. He pivots to the children of Palestine and insists that I focus on the government’s obligations under international law. It’s striking how soft-spoken and earnest he is, but perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised that a man of medicine is concerned with saving kids’ lives.

10.47am: St Milutin the King Serbian Orthodox Church, Point Chevalier

Anna Rankin

It’s mid-morning under a slate sky at the Church of St Milutin the King. The Serbian Eastern Orthodox church is a small, modest building set back from Point Chevalier Rd by a clipped grassy lawn and tidy drive. Above a sign on its exterior in pallid Cyrillic lettering is an Orthodox cross, Byzantine in province.

The church is open to the public every day of the week, and anyone is welcome to visit. Michael Martin, clad in a black cassock with grape vines stitched through its fabric, invites me in. He is a reader in the church, a layperson ordained to read scripture and chants and lead worship. Martin prays a section of the Psalms here most days, and regular members have access to the combination lock; people arrive into a sanctuary of silence to sit, light candles, pray. On Thursdays those who are ill come to receive prayer, and they pray too for the departed, who still exist. “They’re just over on the other side,” Martin says, “just as alive as we are, but no longer in the body.”

Around 70 families, 300 people, belong to the Church of St Milutin the King. Could I join, should I wish to? Absolutely, Martin answers. During and following Covid-19 there was a rise in numbers seeking to join the church, he tells me, with at least a dozen catechumens studying to enter. He offers several reasons for this, but principally, he suggests, “the lockdowns and madness around it shook up a lot of people. Not always in a bad way. They started asking pointed questions about the meaning of life.”

10.53am: Gleway Cafe, Onehunga

Miriama Aoake

I haven’t been to this part of town since my cousin’s wake at the Workingmen’s Club. Parking is definitive, and generous. I order a peppermint tea, despite my hunger for a full English. I’m the only one here at the moment. A lull in service work, unless you are the business owner, is the highlight of the day.

I have lied! There is a customer here. A regular, I judge. He sits outside in a fedora and glasses, doing a crossword in the paper. A woman approaches and greets Crossword Man. They exchange pleasant murmurs and she walks in and orders: cup of tea, trim milk, two sugars. Balance. Here is another woman, with what looks like her mother. She is wearing an arctic fleece jacket, her bronze-grey hair in a ponytail. She orders pancakes and her mother picks a table close to the door and waits.

Two younger women, presumably sisters, enter and order with a toddler at their knees. The toddler can’t be more than two — curious, she wanders into the kitchen. The staff are laughing and usher her back towards her mother, then the family finds a spot in the lounge next door. Another regular arrives and talks to Crossword Man. Her pink floral blouse is cut with a trim black cardigan. A ham, cheese and tomato toastie is brought to her without her even having to ask for it, an indication of her status in this customer hierarchy. In the lounge room, Toddler’s mother is asking her daughter if she wants a marshmallow, and Toddler is intrigued. She squeezes a white marshmallow in her left hand and a pink one in her right. She is unusually tidy, wearing a denim dress, white tights, sneakers, and buttoned cardigan. She attempts an escape out the front door, but escape is futile! At one point she raises her closed fist to her mouth, squeezing the white marshmallow. Close, but she can’t bring herself to eat it. The whole café belongs to her.

There is a sign opposite that reads “HAPPINESS LOOKS GORGEOUS ON YOU”. Below the sign is a table of flyers from Phantom Billstickers and copies of the Coffee News, papers and magazines and toys. A stack of books, including an encyclopaedia, sits untouched a table over. Something is being fried. There is an occasional shifting of trays, pans and tongs. Things being thrown in the bin. Tinkling of spoons in teacups, lifted to mouths and lowered to saucers. Squeals and yelps from the toddler, being chased and caught and released in the lounge. Muted traffic. The engine of the fridge is constant.

11am: Howick Village Cafe, Howick

Angella Dravid

Mums like this cafe. I don’t really understand why, because it’s really dark and the music is porno-style jazz. I can’t stay here longer than 15 minutes because the synthetic saxophone keeps wanting to fuck me.

The mums come wearing athleisure and pushing great big Mountain Buggies. It’s like they’re doing crossfit, but instead of flipping tyres they’re hauling SUVs for babies. This mum group walks towards the cluster of tables in the middle of the cafe which has the reserved sign on it. They seat themselves and then bring out perfect-sized, perfectly prepped plastic tubs containing fancy fruit like berries (not in season!). I know from the semiotics of these tidy containers that their pantries are organised and they clean the dryer lint rack regularly.

There’s also a man reading a book. A full-on novel. In the darkest corner of the cafe. Don’t do that. You’re not better than me because I watched the movie adaptation.

11.10am: School lunch at Waitākere College, Henderson

Matilda, Year 10 at Waitākere College

Lunch today is a red chicken curry and an apple. This meal is especially popular, so few containers remain in the boxes by the time interval is over. As the crowds emerge from their classes, you can see lunch-from-home students looking over the shoulders of those with the school lunches and punching the air. For some students, this is their main meal of the day, so when the lunches taste good on top of being nutritious, they’re in high demand. There are some students with two and even three steaming cardboard containers, balanced carefully on top of each other. We hope this bounty and enthusiasm will last. Recently, the government has announced and confirmed new plans for the school lunch programme, starting in 2025. While those who receive the food are grateful that lunches will still be delivered, we are also worried about the changes in nutrition and delivery of the new meals, and the impact on workers. Up to 2000 jobs are projected to be lost as a result of the change, and specialists have said that the new lunch options are going to be less healthy than the current ones. In the meantime, we Waitākere College students will continue to enjoy our hot meals — especially the chicken curry.

12.01pm: Zumba Club, Māngere Town Centre

Taualofa Totua

Outlining the dancefloor/meeting place/malae of Māngere Town Centre are metal benches, full of people. Masked-up elders in tracksuits, fluoro-pink New Balance sneakers and Mate Ma‘a Tonga jerseys perch patiently. In between the benches are columns holding up the roof, each one painted to replicate palm trees. The instructor’s voice bounces from shop to shop in the plaza, kicking off the Zumba session with prayer. “We thank you [Lord]. We are here to enjoy each other’s company and have a good time.”

Pacific elders respond to the invitation to dance: a hyped remix blend of Vengaboys and a hip-hop tune from the Y2K era. About 60 individuals move with ease into their chosen spots. (In the clurb, we all fam.) Some elders remain seated around the edges, still eagerly participating though just their arms are waving. Red nail polish gleams and the bright seis in their hair turn side to side. Then Daniel Rae Costello’s ‘Another Margarita’ and Los Del Rio’s ‘Macarena’ knit the crowd’s rhythm, calling passersby to join in too. With each song the speed increases and so does the collective energy. One of the elderly men lets out a loud whoop every 10 seconds, with a huge grin.

12.27pm: Yum cha at Asian Wok, Albany

Sherry Zhang

We begin strong with a one-move parallel park right in front of the restaurant. Long yellow lanterns glow, refract and multiply in the windows.

“Table for three please.”

‘Tieguanyin, pu’er, xiang pian, ju hua?”

“… Ju hua?”

We are led to a dining booth, separated from its fellows with dark wood panels. Other groups of diners sit on either side of those wooden carvings, and we eavesdrop on a mix of Cantonese, Mandarin and other dialects. I know they must be doing the same to us.

“Ju hua cha is bit…”

“Well, why didn’t you say anything? What did you want instead? She spoke so fast I didn’t understand what she was asking, so I just repeated the last thing she said!”

“It’s fine, it’s fine. Maybe pu’er, but what you order is fine.”

Before I can jump up and change our order, the waiter is already back with a steaming silver pot of tea. Ju hua it is.

Mum pours the hot brew into small white and blue cups, and we receive them with both of our hands.

The cart follows and Mum peers over her glasses with sharp judgement. She points at bamboo baskets of pai gu (pork ribs) and lotus root stuffed with chicken sticky rice.

Dad points at the siu mai. I quickly grab one with my chopsticks and pop it into my mouth — salty, fresh and tender.

“Oh, it’s got prawn in it…”

“What?”

“It’s fine, Dad can eat the pork ribs.”

“I can have one prawn, it won’t hurt me.”

“No, I’ll order something else, yeah? I don’t want your gout to get worse.”

The waiter returns with another cart of steaming food. I order fried eggplant and fish, salivating at the crispy vegetable coated in umami sauce and topped with flaky white fish. But my enthusiasm is not shared by others on the table.

“I came here with my tai chi friends a few weeks ago. We ordered something really yummy. The chang fen—”

“We have pork, beef, vegetarian, red rice—”

“Is that the crispy one?”

“Yes, it has crispy prawn.”

“Okay! We can have it.”

Mum and I look apologetically at Dad, but he keeps eating his pork ribs. I get up to pour chilli sauce, soy sauce and vinegar into little saucers for us. When I come back, they are both on their phones.

“I’m seeing if your brother is on his lunch break. He can join us.”

He doesn’t pick up, so Mum turns to me.

“He said ‘good luck’ this morning. For your full licence.”

“Thanks, I’ll text him later if I pass.”

“You will pass! Do you want Dad to drive to Silverdale with you?

“I can drive up with you.”

“No, it’s fine, it would psych me out more.”

“We are retired now, anyways — it’ll be something fun for us to do. We don’t have to come in.”

“I’ll see! Do you want more tea?”

I refill the tea cups, and the chang fen arrives. Mum’s right, it is delicious.

12.39pm: Quick Bites Lunch Bar, Penrose

Henry Oliver

I chose lunch by graphic design. Every time I’ve driven past this place, I’ve wondered about the lunch bar with the stoked shark with sunglasses on. Inside, it had all the trappings of an industrial-neighbourhood lunch bar — familiar tables, familiar offering, huge shakers of salt on every table. I ordered what I was recommended — a burger and piece of fried chicken — and watched as the workers of Penrose came through, picking up a sandwich, a punnet of chips and an oversized can of energy drink. I thought about how they all could have gone to McDonald’s or KFC or whatever, but instead came here to buy as much food as possible for as little money as possible from a woman they all seemed to know, but not by name.

1.04pm: Solar noon, Glen Eden

Sam Wieck

whenever the sun’s over wherever it is you happen to be, it has the potential to feel like the world’s furthest-away-close-up magic. you, and everything around you, struck with the perfectly perpendicular vector of light from directly above. briefly calling into question what some have called the very thing-ness of stuff. shadows disappear underneath the mass to which they’re tethered. if only for a moment. for that split second, everything floats. suddenly unburdened by the law of gravity or the harassment of formal constraint. freed from 9.8m/s of drudgery. but there’s clouds today. quite a few. i missed out. not just on that blessed split-second where i get to feel like i’m on top of things. but on the opportunity to commit my final act of rebellion and look directly at the sun.

1.37pm: Auckland Domain, Parnell

Henry Oliver

I’m in the Bowling Club corner of the Domain on what has turned into a glorious spring day. I’m not here for the cherry blossoms, which skipped town a little over a month ago, leaving pedestrian green-leaved trees in their wake, but for rubbish.

A while back I’d heard a rumour, then confirmed in the New Zealand Herald, that there was a pile of old and/or damaged rubbish bins in some out-of-the-way corner around here. I’d been shown photos, zoomed in to the point of pixelation, of a pile of cylinders and spikes, a mass grave of formerly useful metal objects, the victims of the council’s quiet thinning of the herd of central-city rubbish bins a couple of months back.

Wanting to see this rubbish bin graveyard for myself, I try an entrance off Grafton Rd, behind the hospital. The pathway is blocked by a locked gate, and there are no rubbish bins in sight, so I make my way down to Auckland Bowling Club and follow a path next to the green towards a partially obscured fence, topped with barbed wire.

Through the fence I spot the rubbish bins. I take a photo from outside and start tracing the fenceline, looking for a weakness. There’s no obvious spot without barbs, but when I find the clearest, lowest option, I consider climbing over it anyway. I think about when I was a teenager, trawling through the bush a few hundred metres away to sneak into the Auckland Open; I think about jumping the fence at the Kings Arms to sneak into a sold-out show; I think about the jeans I’m wearing and how I don’t want to ruin them; I think about my knees and how they’re not as useful as they once were; I think about middle-aged comfort and my declining sense of adventure; I think about the cruelty of ageing and how there there are already things I’ve done that I will never be able to do again; I think about how embarrassing it would be to get stuck and have to be rescued from the barbs. I think about the low stakes, and console myself that there are still things I’d climb a barbed-wire fence for. But it’s not this.

2.30pm: Hancock’s, Howick

Angella Dravid

I like this place. They have good bacon and eggs. The cafe’s demographic is the elderly — Gold Card Tuesday pops off in here. It’s like entering a shop filled with cotton wool, dandelion seedheads and twinkling grey eyes. Today, it’s nearly empty. There’s a dad with two kids. I feel weird about people-watching around children. I know I’m not a paedophile but other people don’t know that.

I stare around some more. The other couples are eating. When I was a kid, I was told it’s rude to watch people eat, so I look somewhere else. I’ve now been here 10 minutes and already caught the attention of two strangers who’ve independently asked if I’m okay or expecting someone. I tell them no and smile. I take my coffee and Louise slice outside.

The Louise slice tastes fishy. I smell it but all I get are notes of coconut and raspberry jam. Are my senses going awry? I immediately panic because I’m expecting my period, so I stand up and check my chair. Phew. It’s still that classic off-white plastic. Then a seagull swoops over me, directly to the source of the fishy smell — a seafood truck. Classic! I don’t want to sit here anymore, but I can’t go inside the cafe without looking like a psycho.

I watch the driver, who is making frantic calls as the fishy smell intensifies. He’s seen me. I look somewhere else — I look at the truck. “Seafood and Beyond”. It lists frozen fish, surimi paste, cooked prawns and at the very end “vegetable”. The ‘beyond’ bit is one vegetable? Surely that’s a typo. But the big vegetable picture on the truck is of an okra. The driver comes out to unload some boxes. It’s frozen okra. I don’t even think okra pairs well with seafood, does it? When the truck leaves, it takes half the seagulls with it.

2.41pm: Westfield St Lukes Shopping Centre, Mt Albert

Anna Rankin

St Lukes is more than half a century old and one of the oldest malls in the country. I once worked here at a now departed CD and DVD store, which faced outward into the food court and was steeped in the unmistakable smell of Subway. Today, there are a number of new mall employees taking their break in that same food court, following the lunch rush.

Corban has clocked off for the day — he’s worked at St Lukes for two years. He has thick, static, bleached-blond hair and is now gathered with friends around a table. This mall attracts a different class strata to others, he says. “It’s good for groups of people, it’s an opportunity to socialise.” Bridie, his girlfriend, agrees: “There’s also lots of tourists and new people.” The two of them stay, relaxing, for the hour or so that I’m here. They’ve long finished eating but no one comes to move them along or ask in loaded terms whether they might like to order something else as a hint to get going.

When we are not shopping or eating, a mall can be a place to wander in mental rest. Because it lacks obstructive phenomena to negotiate, like footpaths, roads and cars, our submerged thoughts tend to surface through this frictionless experience. Everything, including ourselves, feels curiously under glass, like being entrapped in a snow globe. The mall is white, clean and orderly; it has the appearance of a film set. People come here to experience the ambient sense of strangers who demand nothing of them.

Another inhabitant of the St Lukes food court occasionally types into her phone with little interest, unwraps a Subway sandwich, slowly peels the paper wrapping down as she eats. She stares ahead with the expression we make when listening to a song or podcast that occupies our attention, absent any recognition of the gaze of others and how we might be perceived.

Across the way, two men lean back in their seats, stretch their legs. They are Zlatko and Boris, in their 70s. Zlatko regards me with bemused curiosity. “To tell you the truth,” he begins, “I’m very fussy about food. I do a lot of complaints.” They are regulars to this mall: “We come here, we eat something, we talk. This is beautiful here. Entertainment, beautiful. We look at the ladies, elegant and slim. They are much healthier than those back in the [Yugoslav] war.” They love this place with rare, intense devotion. Everything is here, Boris says: “The banks, we can do whatever.” “Look at the escalator!” Zlatko cries, gesturing to the contraption. “Look at its steps. Do other places have steps like it? I don’t think so. Look at the floor, it’s very shiny, no rubbish. There’s a lot of rubbish in the city.”

2.43pm: Hancock’s again, Howick

Angella Dravid

A woman across the road is saluting… at nothing. She’s got a steely gaze and is looking far off into the distance, but there’s nothing to see on this side of the road. There’s a small community hall and public toilets. She crosses the road… and gets into her car. Was she… saluting her car?

2.47pm: Red Cross Shop, Karangahape Rd, Newton

Miriama Aoake

I just had lunch and a gin and tonic with dear family friends. They’d been here earlier and came away with some goods; one of them volunteers at an op shop so has a level of skill that the rest of us don’t have. My sister pulls out a yellow-butter number. “This is a bit of you.” It is a satin tube dress with an elastic band on the bust. Versatile — could be a skirt, could be a dress. Could be a lot of things. It is not a bit of me.

She pulls out some tartan pants and Tweety Bird pyjamas and says again, “This is a bit of you.” Sometimes she is taking the piss and sometimes she is being earnest and if you get it wrong you feel stink. She always comes away with something and today she finds an Olivia Laing book about being alone. Olivia Laing is not alone! She is going home in my sister’s bag. There’s a crowd here hunting for last-minute Halloween items and if you’re absent-minded you are in the way. Even if you are present- or future-minded you are in the fucken way. I am trying to sink myself into the racks of clothes to be mindful. It is not a good idea to scrawl in a jotter pad because a single budge on your elbow will scar your gentle notes. You’re supposed to come here prepared with an idea of something you need. That’s why you always eat before you go to the supermarket. My sister rescues Olivia Laing and we hop next door. We have cracked it: a copy of The Rise and Fall of a Young Turk, Rob Muldoon. And because we are sisters we parrot each other. Clyde Dam, Think Big! I mumble, “Doesn’t give my opponents much time to run up to an election, does it?” Two young girls are raiding shorts and chatting in French. Rainbow Warrior! Do we all think that, hearing French? There’s collections of dead-stock soaps and smelly bathroom things that have been offloaded. Bruno Mars is playing and my sister says, “It’s your favourite song” and I punch her in the leg. See? It takes time but she’s revealed the bit. She’s been taking the piss all arvo. It’s that ‘don’t believe me? just watch’ song.

I make my sister pull All Black biographies and pose with them. Later, I will send those photos to our dad, who won’t respond. The next day we will complain to our mum, but it’s clear that every sport is sacred in this family. There are old VHS tapes here from United Video. Or maybe Blockbuster. We have to buy one. There’s a Xena universe section and I tell my sister Hercules is pro-Trump. Of course he is. A few more jabs of “this is a bit of you” land as we head for the exit and I continue to threaten to punch her for it.

Finally, we head to Vixen even though I don’t want to. My sister points to a “fake Issey Miyake” that is nice but not nice enough to have a staff member fetch a ladder or a hook and hoist it down. We clutch sequins and leather and tassels and velour because we both love tacky, but we leave them where they lie. My sister is meeting friends because she is social and I am going home because I am not.

2.51pm: The Charity Boutique, Howick

Angella Dravid

There’s a school kid here with a woman I’m assuming is her mum. Maybe the schools have been let out early today. I remember being dragged into shops by my mum when I was a kid. The mum tells her kid to let her know the fit of the skirt. The kid comes out and doesn’t say anything, which infuriates the mum. So the mum sticks her fingers into the waistband. This is like when you measure how much water to put into the rice, except you’re measuring the right level of fat for your waistband. I try to get further into the shop but this is the smallest op shop I’ve ever been in. I have to lose weight to get to the back shelves. I’ll come back next year.

2.52pm: School pick-up at St Cuthbert’s College, Epsom

Charlotte Muru-Lanning

Cars begin to fill the leafy side streets one by one, some slipping into spaces along the curb while others disappear into the underground carpark. A lone parent leans against the hedged stone wall by the front gate, while across the road, two workers from the nearby hospital settle on the berm: one with a vape, the other with a mug, perhaps tea or milky coffee. Plaid-uniformed students start trickling out of the gates. Parents and grandparents, though, mostly mothers, sit waiting in their cars or step out briefly to greet giant backpacks. At 3.01pm, the line of cars stalls in stillness — a strange quiet spreads amid the visual chaos.

I jot down the parade of cars in view: Porsche Cayenne, Volkswagen Tiguan, a white Lamborghini, Range Rover, a grey Tesla, another Tiguan, a white Mercedes-Benz G 63, Audi Q7, BMW X7, another white Tesla, Mercedes-Benz G 63, BMW M series, Mercedes-AMG GT, Range Rover, Tesla, BMW, Porsche, Porsche, Tesla, Audi Q7. These are vehicles that purr and growl, sounding like triple-figure price tags. Then, as if by magic, the back door of a white Tesla swings open, lifting like the wing of a futuristic flying creature. A plaid-clad child darts in.

2.57pm: Rosebank Rd, Avondale

Dan Taipua

I work from home at my three-bedroom house in Avondale, so things are generally slow in the daytime. It’s a good set-up, but I sometimes miss my shared office in Ponsonby with all the shops and cafes and media offices around — all the things that aren’t really work. I can’t fit a large photocopier in my home office, so mid-afternoon sends me on a walk to Avondale Library to print some large documents.

If I’d arranged my day better, I might have left for the library well before school let out; traffic is heavy at hometime, all across Auckland, but here we have a particularly strong current. Avondale Kindergarten, Te Kura o Pātiki Rosebank School, Avondale Intermediate and Avondale College are all plotted back to back in a large suburban block, and three o’clock starts a stream of students away from the Rosebank peninsula.

Parents are already gathered at the primary as I approach. They walk across adjoining fields alone or in small groups, park in work cars and vans along the main road, or hop off buses to collect their tamariki. The school itself is a wonder of modern Tāmaki — it wears the Māori name Pātiki (the flounder of the nearby waters), displays sponsorships from local businesses along its fenceline, and the buildings are decorated with a bright rainbow motif.

The rainbow is apt. I see every stripe of student flow out of the school: a young girl in sari, a boy with his pakul on, another wearing the printed flowers of his island on his shirt. It could be a special cultural day at the school, or it could just be Wednesday.

My mum actually taught at Rosebank School for a while in the 70s and says this rainbow was ever so: the children match the workers in Avondale’s nearby industrial zone, the stretch of factories and warehouses at the opposite end of Rosebank Rd. Watching a number of dads walk their young kids home, I wonder if they’ve come off the 4.30am to 2.30pm shift my own dad worked when he was a truck driver.

The seasons change quick in late October, and I’ve left my home dressed for spring rain instead of spring heat, so I cross the road to one of many dairies for a cold drink. The intermediate and college are getting out now and there’s fewer parents around, while teens flow into the dairy for after-school snacks and pre-sports supplies. These are growing kids, and I’m lightly astounded that some of them are almost my adult size. The surprise fades when I realise that I was also almost my size when I was their size, built from the same stuff at different times.

Away, and almost at the library, I’m now properly surrounded by the third-largest college in Auckland. These older kids travel farther distances, and their uniforms fill up the Avondale town centre, from which point buses carry them east or south or further west into Waitākere proper. It’s almost exam and assessment time for the senior students, and they’ve put in a full day that will soon match their adult lives. I finally reach the library for my own work, having walked the timeline of education in our town — but I forgot my library card. I think I’ll knock off for the day.

3.10pm: Hospice Shop, Howick

Angella Dravid

There’s a cute group of elderly women at the counter fawning over something. It’s silver and shiny but I can’t quite catch it. All I know is that the lady holding it is beaming with excitement. The woman at the counter tells her it’s her lucky day because she can have it for a donation. Her friend offers to buy it for her. Then another woman from across the shop offers to buy it for her. I feel weird, like maybe I should also offer to buy it for her. It’s like this is an auction. I look at the object they’re all bidding for: a silver high heel with the words ‘Wine Lover’ printed on the inner sole in a girlish font.

I know this is a Kodak moment. I stand awkwardly close, trying to figure out how to capture this. I tell the lady at the counter that I’m a writer from Metro doing a piece on A Day in the Life of Auckland. “I’d love to take a photo of you all.” She smiles and says that’s lovely but she can’t speak for everyone else. I go to the group of women and ask if I can take a photo of them. The other women step away and reveal the central lady holding up her new prized possession. I ask for her name. “Margaret Taylor,” she says. Everything about Margaret is endearing and sweet and I feel for the first time that I’ve seen something worth writing about.

3.24pm: At home in Eden Terrace

Saraid de Silva

I spend a lot of time isolating myself, shifting appointments, not replying to messages/emails, all this effort into making time to write, and every day I feel I squander it. Having a workspace as clear as I can reasonably get it helps. Afternoons are less stressful. I replaced my desk with this round dining table and immediately mourned my lost forearm resting space. It’s cute for having dinner with friends though. The screen is blank because I was about to start working on a slideshow for Verb Readers and Writers Festival in Pōneke. It was a bit earnest in the end, but what can you do?

3.27pm: Howick Village Grocer

Angella Dravid

This grocer has a lot of German chocolate and Eden Orchards Cherry Juice. I can tell if a shop is out of my price range when there’s a Himalayan salt lamp or cherry juice on the shelf, and this shop qualifies. Whoever said Howick has a stuffy, conservative population is clearly out of touch. Maybe there is an older demo here, but they’re not slowing down with technology and trends. I end up buying cherry chocolate. The man behind the counter asks me if I’ve tried it before. I tell him no, and he says, “Oh, okay, you can try it” … and gets a cherry chocolate from behind the counter for me to try. WHAT?! I buy extra stuff I can’t afford because of the nice gesture. Has it always been this nice in the community? I don’t think so. Once I left a still-working microwave outside on the curb, and the next morning the door was kicked in.

When I walk outside, I see Margaret again who asks for more information on when and where this will be published. I tell her it’s a quarterly magazine but it will also be out online. I actually have no idea how to answer her questions, so I ask for her email address. She says she doesn’t have one. It now comes across as suspicious that there’s a bitcoin ATM in Howick. If some of these residents don’t have emails, I’m sure as hell they don’t have crypto. I tell Margaret maybe I can send an update to the op shop and then she can get it there. I say goodbye and walk away worried she has high expectations. Then I feel a sudden kind of internal warmth.

Somewhere in the middle of trying to observe the communities around me, I somehow made a friend. Margaret Taylor, I hope you have a very Merry Christmas, and thank you grocer for the cherry chocolate!

4.03pm: Karamatura Heritage Farm, Huia

James Borrowdale

Perhaps once a month, seeking to fill those difficult hours between the end of the school day and the beginning of the evening routine, we visit the local friendly one-eyed cow. I’ll pick up my daughters — aged four and two — from kindy and head west into the Waitākere Ranges Regional Park, the bush clawing at the edge of the road until, rounding a bend, the one-shop village of Huia emerges for a moment that is very soon ended by a single-lane bridge and more bush. And so the three of us find ourselves — this time on Metro assignment — turning right and rumbling over the cattle-stop at Karamatura Heritage Farm, a council-run farm sitting in an east-facing lap of the ranges above, which seeks to provide insight into the area’s agricultural history.

The flock of geese parts as we edge up the gravel road, spring lambs hopping behind their mothers or burying faces in their udders. From the carpark, chickens and ducks scattering from under our feet, we set out across the field to where we can already see Heather-Rose, lumbering under the weight of her 17 years, her left eye lost to cancer. She accepts the carrots from my hand, as I again show the girls — still too timid to try themselves — how to flatten your palm so as not to mistakenly offer a finger. Heather-Rose’s big wet muzzle tousles my hand as the girls tentatively rub her sun-warmed belly, malting hair released into the breeze and lit up by the low sun. We set up a picnic and let the minutes tick by in aimless conversation, the water of the Manukau Harbour below similarly activated by the late-afternoon light, twinkling through a veil of green. I think absent-mindedly of my own rural Canterbury childhood, during which a hand-milked house cow was always part of the operation, and how pure it feels to share part of my own heritage with these two small Aucklanders. The temperature drops, but I’ve left their jumpers in the car; we say goodbye to Heather-Rose, dodging cowpats as we head back across the fields, into the car, and then into the evening routine.

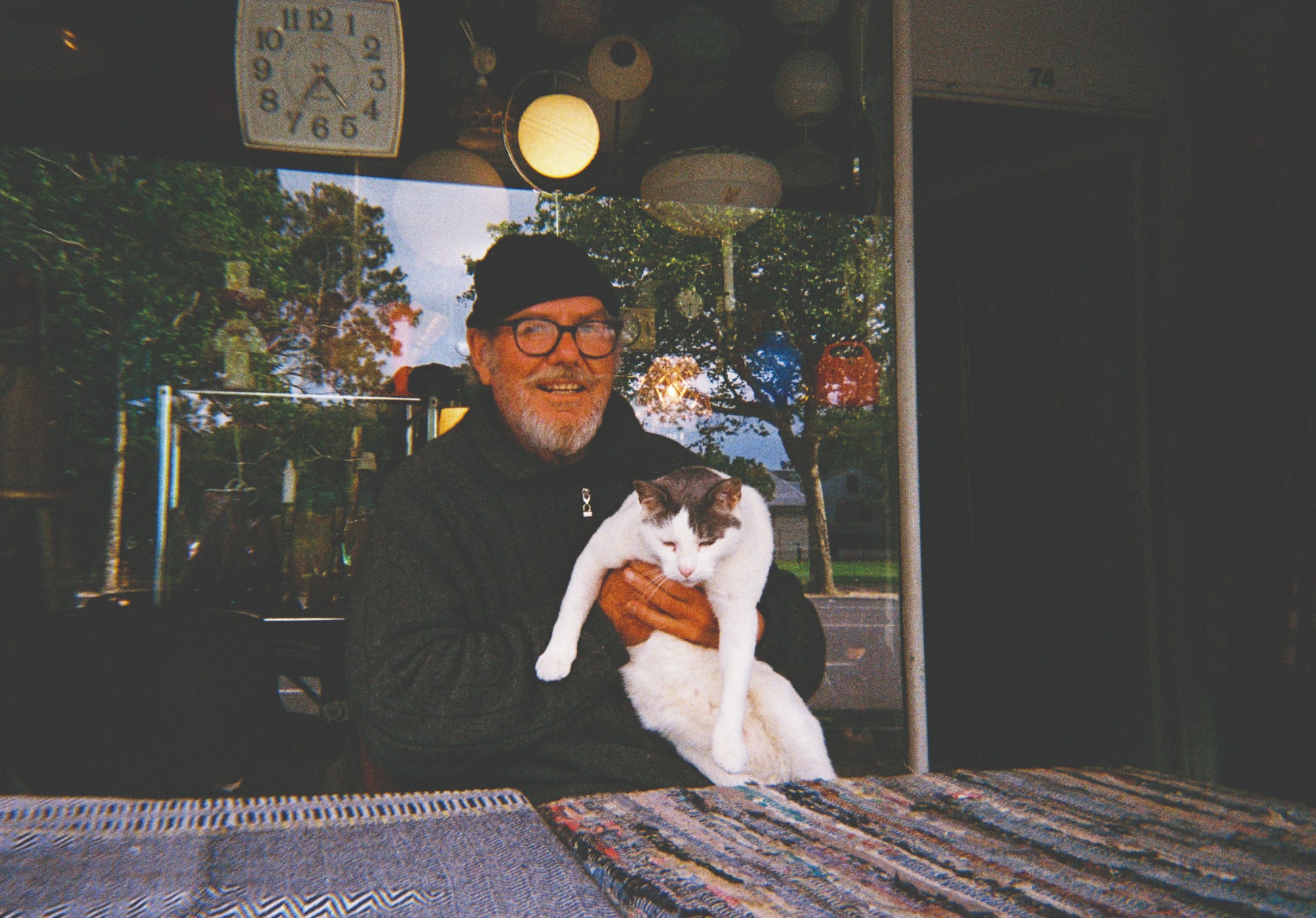

4.28pm: Robin the cat at Real Time, Ponsonby

Charlotte Muru-Lanning

It’s dinner time. This afternoon, like most days, Robin, a neutered tabby, is dining on a bowl of his staple: “cheap and cheerful Whiskas” served by Peter Rogers. Rogers has been running his eclectic shop for 51 years, and Robin spends his days and nights there among an array of suspended art deco light shades, vintage cocktail shakers, carved salad bowls, figurines, furs, fountain stools — ornaments of the past. Born eight years ago right behind the shop, Robin has lived here ever since.

These days Robin lives the relatively stable life of a shop cat, but he has a slightly more free-wheeling sister, Princess Tiffany, who, though also a Ponsonby resident, lives as a street cat. Their brother Batman, once bullied by his two siblings, now lives a quiet life at Rogers’ home. Starting life on Ponsonby Rd has given all three a keen sense of traffic safety. “They understand the dangers of cars,” Rogers says — an especially good thing for Robin, who can most often be found basking in a perfect ray of sunlight in front of the shop, perhaps on an antique table, a 1950s stool or even a stack of records, entirely unfazed by the tooting horns and revving engines of passing traffic. Very soon, as the working day comes to an end, Rogers’ nightly street-side salon will soon begin, attracting a who’s who of Ponsonby for drinks at the front of the shop — Robin included, of course, forever the unbothered fixture of the scene.

4.35pm: Te Komititanga Square, central city

Julie Hill

She stands silently, a small figure in a bustling thoroughfare holding a Palestinian flag. Propped up beside her is a poster that reads “Genocide, made in the USA”. It’s one of several she’s had made up, which feature art by American political cartoonist Mr. Fish and quotes by the historian Ilan Pappé and Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters.

It’s Wednesday, 30 October 2024, and Israel continues its invasion of Gaza for the 383rd day in a row. Just over a year ago, the military wing of Hamas, Gaza’s governing body, killed 1139 Israelis and took more than 200 others hostage. Since then, Israel has killed at least 44,000 Palestinians, though many credible reports estimate a much higher number.

Marika Czaja calls it genocide. A regular at Auckland’s Saturday rallies in solidarity with Palestine, in May she decided to take her campaigning up a notch, staging a daily one-woman protest in front of the US consulate. “It upsets me the way the US says ‘Please stop the war — and here’s some more weapons’,” she tells me.

When the US flag comes down for the day, Czaja travels to her late-afternoon possie in front of Commercial Bay at Britomart. She’s here every weekday and will continue “until a proper truce in Palestine or I kick the bucket, whichever comes first”.

Some people look right through her. Some don’t look at her at all. Others stop to talk. “There are people saying thank you and people giving me hugs. I’ve received some roses from some young women. Umpteen offers of people asking whether I need something to eat or drink. Of course, some people raise their eyebrows or shake their heads, but it may not be disapproval of me. They may be disapproving of the genocide.”

Are her loved ones worried for her safety? “Some are. I’m not worried at all. There are people around me all the time. And I’m old and small so I feel quite safe.”

Czaja, 84, was born in Hamburg in 1940. She was a volunteer at Waiheke Community Art Gallery for 17 years. Before that, she protested for indigenous rights and against uranium mining in Australia. “Because I was born in Europe and remember what happened, I try to stand up for injustices,” she says. “My family’s home was bombed. Our situation was awful enough but I would never dare compare it to what the Palestinians are suffering at the moment.”

She’s horrified by Germany’s pro-Israel stance, thinking it derives less from guilt towards Jewish people and more from racism.

As for the New Zealand government, she calls on it to recognise Palestine as a state, issue humanitarian visas for Palestinian refugees and expel the Israeli ambassador. But she doubts it will because, like Germany and Australia, “they’re spineless. They are terrified of the actions the US might take in retaliation.”

On this single day alone, 110 Palestinians have been killed in northern Gaza, but it’s been a long year of war and this many deaths in a day is no longer unusual. There’s not even a mention of it on the news. But in Australia, there’s a yarn about Radiohead singer Thom Yorke storming off stage in Melbourne after being heckled about his silence on the crisis. The tantrum is brief: he returns after a few moments to play ‘Karma Police’.

Can one person make a difference? I ask Czaja. “Hannah Arendt said evil thrives on apathy and cannot exist without it. We look back to World War II and say, how did people allow it to happen? All you need to do is look around and you see how it happens. It makes me very sad because when I was growing up, the young people were so convinced that we could turn the world into a better place.”

5.03pm: Queen’s Wharf, central city

Salene Schloffel-Armstrong

It’s 5pm and people are scurrying downtown to the ferry terminals, rushing with coats and laptop bags. At the end of Queen’s Wharf some take photos of the departing Pacific Explorer cruise ship as it is towed out by two Coastguard boats. Others eat gelato, gossip or just lie in the sun.

The unassuming end of the wharf has become one of my favourite public spaces in Auckland. The vibe here shifts fluidly with the many moods and textures of the city, for some reason more noticeably than many other inner-city spaces.

Every time I am down here, someone is trying their luck, sitting and fishing off the end. Today at least eight lines are set. Once I observed two men fishing alongside each other — previously strangers, no common language between them — spell out each other’s names with their hands and learn them, before one of them left to go home with his catch.

In discussions of livability in Auckland, in the ongoing crisis of housing we have, we tend to forget that spaces to freely encounter each other outside are also necessary in a city. And the provisional, open nature of this one feels like a little glimpse of old Auckland, and possibly a future Auckland, too.

I’ve recently become obsessed with this one photograph from Auckland Libraries’ heritage collection, of seagulls flying just above the white caps of the Waitematā, taken from a city wharf in 1910. It is this sense of timelessness that I feel here. For as long as people have lived on this isthmus, this water, these birds, this wind have all been here alongside us.

5.25pm: Te Komititanga Square, central city

Two waste management workers replace rubbish bin bags.

6.37pm: St Kevins Arcade, Karangahape Rd, Newton

Emily Rākete

Ten years ago or so we would have political meetings just around the corner from here. An experimental metal band blasted black and white noise from the next room over and we’d huddle, planning protests and direct actions. Hurling whatever we could against the palaces of the rich. We still haven’t torn them down. Tonight we are huddling over plates of pasta and glasses of wine, furtive back-room lamplight switched out for candleflicker. She’s never been more beautiful. The setting sunlight scans down her face and makes a PDF of our years together. But outside, a man huddles in the dark of the arcade with his hands up to the brazier. He doesn’t want to bother anyone. He’s just cold. Someone in an apron goes out, says a few words.

This scene is the fault of none of us individually. This city is not a place for human beings, and so my own human life has affected nothing about the encounter. Auckland is not a place of individual people with individual lives, but of collectivities defined by their relationships to the production of wealth. Who will own and who will work, who will command and who will be commanded. Who we will be — the warm animal striving of human beings trying, despite it all, to live — is bound by the cold dictates of capital.

Capitalism needs the poor and miserable, and so it impoverishes and immiserates. Interest rates get raised, unemployment spikes–, price inflation slows and the rich sleep easy in Remuera and Epsom. Only we freeze; only we starve. One class, constituted by its exploitation of another, rules. For now. And the man nods, just once, and then goes.

The system which produced this encounter is something that has been made, and so it is something that can be unmade. It will require the working class to meet not around the brazier, and not across the dining table, but huddled in the back rooms. Planning how to break free.

6.44pm: Great North Rd, Western Springs

A woman runs for the number 18 bus, and makes it.

7.17pm: Sunset, Piha

Bob Harvey

I arrive early at the carpark at the old radar station site above Piha. For me, the place is haunted by ghosts and death — the missing pieces of a jigsaw I have been obsessed with for nearly a decade. A mysterious place without answers or resolution.

These are some of the highest sea cliffs in New Zealand. The radar station, where my mother served her war years, once had its own barracks, cookhouse and watch tower. Standing on the tower once, looking through binoculars, my mother saw a Japanese sea plane buzzing over Auckland on reconnaissance, to be collected later by submarine.

A rock by the parking area marks the site where, in 1948, some of the first galactic radio waves were detected after a journey all the way from the Crab Nebula in the Milky Way. Radio astronomy was a primitive field then, but the work done by the pioneering Cosmic Noise Expedition on the cliffs to the south of Piha laid the groundwork for further important discoveries — pulsars, quasars, cosmic microwave background radiation — and research into the deep processes of the universe.

I sit on the seat above the Tasman where Cherie Vousden was last seen, on 22 December 2012, laughing, with a bottle of wine, waiting for the sunset. She was 42 years old, vivacious, beautiful, a mother of one — and she has not been seen since. Earlier this year, I appeared with others in a television documentary, Black Coast Vanishings. Over a million and a half New Zealanders watching it were drawn into the mystery of these Piha cliffs. All year those viewers have stopped me and passed on their own thoughts and ideas about how six different people, between 1992 and 2020, simply vanished without trace from Piha, not a shoe or backpack left behind. Some of the people I’ve spoken to have had visions or dreams — all are convinced that there is more to be learned about these disappearances and their mysteries.

Today, there’s half an hour to go before the sun will vanish. I think about what we have done with the day. How have we used it? Did we waste it? Did we misuse the day, carelessly, as just another of the many in our wretched, stressful lives? Did we think about the hell that people are going through in Gaza and Ukraine and so many other places, or did we shrug and get on with our coffee-sipping? This is what a day is when it starts to end — a time to reflect that we will never have it again. Not this day. Never the same.

But this sunset is special, as tomorrow is special, as tomorrow’s sunset will be. The clouds part as the sun turns into a blazing orb. It’s got only 10 minutes now to start lowering itself gently into the Tasman. The surf below roars against the cliff, and the swells come towards me as massive sea troughs, as if they’re acknowledging the sun falling into their depths. This is the moment when all of the colours in the clouds, the sky, the atmosphere, start changing.

The wonderful Gretchen Albrecht captured these moments in her 1973 painting Golden Sky Stream, on show now at Te Uru in a new exhibition called Liquid States. She paints the sunset moments with rich purples and blues, paying homage to the departure of the day and the arrival of the night. “Colour is a voice,” says Albrecht. “It’s what you speak with, pigments on canvas.”

I don’t think anyone has captured the intensity of a New Zealand sunset quite like Albrecht in these works from the 1970s and 80s. During much of this time she lived down the road from me in Titirangi. Looking now at the real horizon above Piha, I feel that I am looking and falling into Albrecht’s boundless skies, her molten streams of yellow, oranges and crimson reds. As curator Sue Cramer says in the Liquid States catalogue, the intense colours on Albrecht’s canvases “call forth thoughts of burning sunsets, apocryphal red skies, or the upsurge of heat before volcanic eruption”. All of this is unfolding in front of me. I am in awe.

Then I notice below a group of people who have emerged out of the bush line. Two handsome young men, accompanied by two beautiful women. They move into the fern belt. The men take their shirts off and start saluting the sun’s rays, their arms outstretched, welcoming the deepening colours. The women respond, taking their shirts and jackets off, and together they pay an ancient homage to what is unfolding. I am transfixed and bewildered. Who are these glorious people who have emerged from the forest to pay their salutations to the celestial orb? I feel I’m witnessing something special, secret, but I simply cannot look away.

I’m overwhelmed with a feeling that this sunset — this “splendor of ended day”, as the poet Walt Whitman said — is witnessing the death of us. We are not unlike the sun; we flame and flare in our youth and our burning fire dies within us as we age. This sunset is simply not a passing gesture of nature, but a powerful, consuming farewell to the day and our life, a deeply significant moment that we shouldn’t ignore. “Wonderful to depart!” said Whitman. “Wonderful to be here!” The scene is much more than a postcard.

But there is one last thing I want to observe — the reason I am still sitting here, fixated by the sunset. I have come to see the green flash.

The atmosphere is perfect. The horizon clears; the clouds, mist and fog lift. The green flash — a phenomenon the early settlers were riveted by — appears for only split seconds. It’s when the light and the colours of the sun merge in an instant and give an iridescent green blast across the horizon, so quick that only the sharpest eye catches it and the sharpest brain records it. It’s best to view the flash from a hilltop, high above the sea. You have to fix your eye on the last moment of the sun’s departure. Count to 10 and be prepared.

It happens today as quickly as I remember. In awe of the flash, I shout to the sun worshippers below, “Did you see that?” They don’t respond. They are in another space, another place. Later, when I drive home in the rapidly closing darkness, I wonder if they existed at all. Were they real or unreal? Were they the missing departed, showing themselves to me in that moment of surreal bliss?