Sep 3, 2024 Art

When Derek Jarman died in 1994, I was four years old — not nearly old enough to comprehend the crucible of terror and guilt gay men around the world lived within. Effective HIV treatment was still decades away. The pressure they lived under seems nearly incomprehensible now, with the ready availability of antiretrovirals meaning unprotected sex no longer bears the weight of death like it used to. (That said, we are still, frustratingly, without an emphatic cure.) But, like so many art-fags before me (and invariably after me), I eventually discovered Jarman in my early twenties. As with any adolescent feverishly collecting idols, I immediately acquired him as a pocket Christ, a talisman against the straight-obsessed mainstream which hadn’t yet claimed the rainbow.

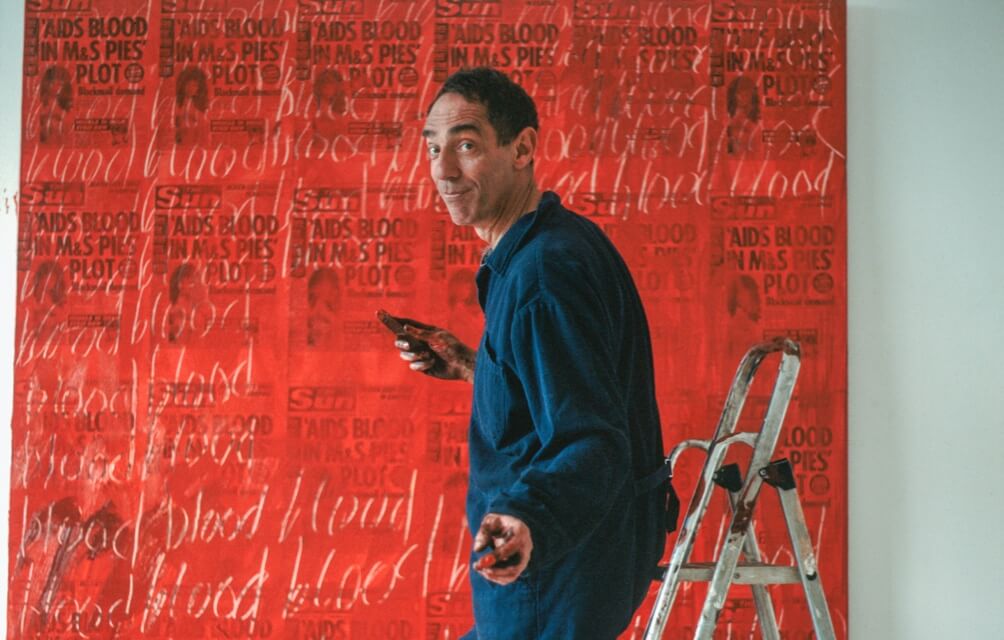

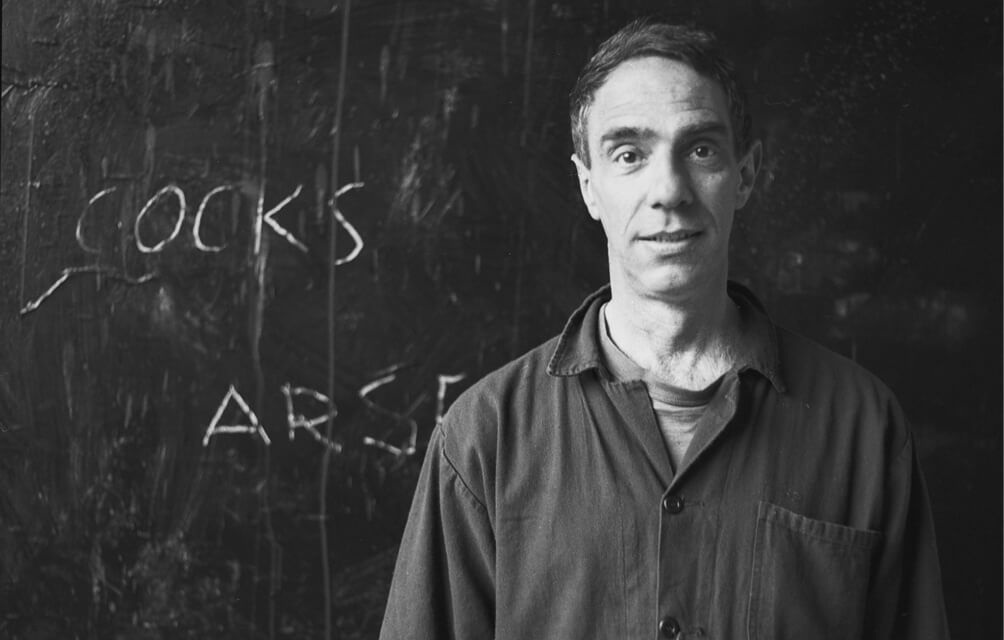

Even by current standards, Derek Jarman — painter, writer, filmmaker — has an enigmatic stubbornness to him. There’s a puckish quality to his body of work, which resists the lazier classifications thrown his way. He is neither all perverse and camp nor entirely the devoted traditionalist chasing nostalgic visual pleasures. Though primarily known for his film work, Jarman’s practice as a painter predates his filmography, and it’s arguably a painterly formalism that he brought to the medium of film, a care for individual frames, a focus on the aesthetic labour of composition. Despite this, and despite the attempted dilution of his subversive character toward the end of his life, he was certainly not exclusively the mild-mannered gardener the British middle class would now prefer him to be.

If anything, Jarman asserted himself against a tendential lionising of American culture in postwar Britain. From the perspective of austere 1950s England (a time long before the flamboyant New Romantics), the United States was generally a place of artistic longing and exodus. In the 1960s, artists in the burgeoning pop-art scene like Yorkshire-born David Hockney sought the sunniness of California — its endless summer, its swimming pools — as subject matter. Jarman, however, resisted this pull, critical of the associated orgies of consumerism and ensuing spiritual rot. Forgoing the transatlantic scene, he began chasing a specifically European grace and the roots of that grace, evident in his wistful biopics Caravaggio (1986) and Wittgenstein (1993). Across these works and other films, he remained a conjurer and purveyor of shaggy homoeroticism and sadomasochism — evident in The Garden (1990) and perhaps best exemplified in his debut feature, Sebastiane (1976), about the famous martyred saint.

In Sebastiane, we have a version of the much-pornified barracks romance, but instead of the fetishised military trappings commonly found in post-VHS iterations (boots and leather, the garb of SS officers), Jarman quite literally denudes his soldiers of anything but their perfected male forms, finally shooting the titular saint until his body is pierced with arrows, like a bukkake scene crossed with a perfume commercial. In all this, Jarman showed an avowed preference for antiquity over the cheaper, more rabid eroticisms of contemporary popular culture. The other thing that Jarman had that other independent gay filmmakers of the time (such as Californian Kenneth Anger, whom he was influenced by) lacked was an abstract poetic sincerity, an aversion to the imagistic ironies of pop, a genre that valued titillation for its own sake without tethering it to extant canons. He was a traditionalist, but only inasmuch as certain traditions were available as launching pads for sensual subversion. For Jarman, the germs of radical sensibility existed in the past as much as they did in the future. He robustly excavated history and shook its faggots out of their ornately painted closets.

That Jarman frankly explored his sexuality through abstract and symbolist lenses is something decidedly lost to us now — those nuances were made possible by social and environmental factors no longer in existence. Where Jarman’s was a climate of mortal repression, where silence in and around the Aids crisis literally meant death, ours is one without the urgencies of libidinal forces trying to make themselves heard. Sex has been sapped of its radical content. Jarman’s hijacking of Renaissance and neoclassical aesthetics to make something like a homo neo-baroque — he transported the male nude at the same time as advertising lenses (notably Calvin Klein) were doing practically the same — is impossible to imagine happening today. Contemporary media modes pay so much lip service to representation, mimetic ideologies of over-correction that trap the image in clumsy political strategies (as if images not overtly prefaced with political intention cannot find an audience willing to read it there; as if the will to art was secondary, even dirty).

Where Jarman married sex with romantic genres of visual beauty — overtly queering those genres for a public made queasy by diseased queers — representations of queerness today have moved beyond artful formalism and often spend their newfound freedom on assimilationism, on shaving the sharp angles off the ‘queer experience’ (whatever that is) so it may fit more easily into the heteronormative implements of coupledom. (Dating and marriage and mortgages are the realisation of the dream, we’re told.) No longer art, no longer willing to engage with prior canonical flows as Jarman did, queer representation is content with wrangling consumer rights via an existing programme of civil and social justice. Modern queer advocacy abides by the set texts of liberal posturing and a circulation of pride-themed infographics; the appetite for beauty has been replaced by facile righteousness and the apparently untouchable (and infinitely renewable) nobility of the victim. Perhaps even in Jarman’s time disillusionment with media helped nudge him into the fruitful seclusion of Prospect Cottage at Dungeness, Kent.

In his famous turn to gardening, Jarman sought a type of pastoral existence, siloed from the contemporary ugliness he found himself subjected to. The move was pleasingly discordant with his more antagonistic sensibilities as an artist, but also an extension of them; a queering of repressive English civility, a flight from the decimations of Margaret Thatcher’s England, a return to nature against a world haranguing homosexuals for their unnaturalness (with Aids upheld as a negative proof thereof). It’s a return most poignantly documented in Jarman’s journals during his Aids-related decline. The garden at Prospect Cottage was and still is a solitary oasis between heather and sea, which friend and collaborator Tilda Swinton fondly recalls encountering with Jarman while scouting for a film location (specifically, a bluebell wood). From the late 1980s, Prospect became something of a laboratory, a third space — not office or home — in which ideas germinated and were incubated, and of which Swinton in her foreword to Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook (a 2022 selection from Jarman’s journals) writes: “Just as Derek was self-determinedly dedicated to process above product, to collective work, to empowering voices that might feel alienated, my excitement about [his] vision for Prospect Cottage lives in its projected future as an open, inclusive and encouraging machine for the inspiration and functional working lives of those who might come and share in its special qualities. Qualities that, as a young artist, I was lucky enough to benefit from alongside Derek and so many of our friends and fellow travellers.”

The garden is a fertile site for explorations, especially as seen through Jarman’s swansong journals, published as Modern Nature in 1991. Though blighted by illness, the artist continued to reach for more profound conceptions of the biosphere, one in which sickness and death are inextricable from the beauty and genius of the natural world. A far cry from the botanical etchings of Victorian naturalists, Jarman’s meditations at Prospect Cottage are a kind of alchemy, constructing from his own mortal terror an oblique and consummate celebration of life in its manifold forms — a celebration that encompasses sickness, sex and death as key blooms in a necessarily varied bouquet. Ironically, Jarman’s green fingers insinuated him into middle-class respectability. When he appeared on a British television special devoted to gardening, the segment carefully avoided mentioning his profile as a transgressive artist. This veneer of respectability helped cement his posthumous status as a (reluctantly acknowledged) national treasure, a change from the media vitriol he received in the late 1980s after being one of the only high-profile people in Britain to publicly disclose their HIV status. In queer and avant-garde circles, it was this disclosure that had practically canonised him, seen as a fitting turn for his fearlessness as an artist. “I’ve always hated secrets,” said Jarman, “the canker that destroys.”

In looking across Jarman’s film collaborations, his painting, his writing and finally his gardening, you might isolate the unifier (besides sodomy) as the idea of wilderness. Certainly, Prospect Cottage is a shrine to this, in which a portrait of teeming life in largely healthful disarray abuts the perceived chaos of the contemporary. As an antidote to the jadedness and cynicism that come with dark global currents and a media intent on amplifying spectacles of doom, Jarman offered the idea that difference is not an insurmountable road stop. Rather, difference is the key to a thriving ecology, so long as it finds a gear of complement — as opposed to defensive strategies of kill or be killed. In Jarman’s grasp of traditionalism through an avant-garde lens and his anachronistic marriage of baroque symbolism to modern camp, the idea of complementary wilderness is very much alive. His whole agenda can be seen to come into focus on his death: in the years leading up to it, he sought to enclose sickness and death in soil shared with sex, botanical beauty, the will to art and complexity of history. Jarman’s life-as-art and art-as-life deconstruct (or try to) the very nature of a problem, bidding patience in the face of the problem until it reveals its hidden blooms.

Jarman also acknowledged threats to happy biodiversity. As he wrote in his first published diary, Dancing Ledge (1984): “As the decade wore on, the ‘straight’ world, I realized, was a giant vegetable nightmare from which I’d miraculously escaped. Like everything mundane, it made every effort to keep young men and women in its muddy waters.” This, then, is a remaining and suitably conflicted Jarman-key: that normative lifestyles are the anti-wilderness, the anti-botanical; that manoeuvres of queering shouldn’t clip their own wings and settle for the patronising securities of the real estate portfolio, the marriage, bovine reproduction, etc. Especially if these fabled securities hold people to ransom against ‘authentic’ living or stop them from sharing their views on the barbarities of our world, like, I don’t know, genocides (just off the top of my head). Jarman’s ultimate insight could be that enchantment follows risk. That he could hold to that flare, even after succumbing to a virus during a pandemic, should give us a sort of hardy hope in the tangled wake of our own.