Jul 6, 2022 Art

Something monumental is happening up north. I’m referring to the grandiose monument (or architectural eyesore — opinions vary) that has popped up in Whangārei’s Town Basin: the Hundertwasser Art Centre. It’s been in the pipeline for nigh on a decade.

Sharing the space, and to many eclipsing the fanfare around the Hundertwasser memorial, is Wairau Māori Art Gallery — a space which, as of its soft opening on 20 February, credits itself as being the nation’s first public gallery of Māori art. The gallery itself, tucked into the centre on the ground floor beneath a permanent exhibition of Hundertwasser works, is admittedly a modest space. Yet despite its size, Wairau involves heavy-hitting players and has a strong vision, poised for maximum impact.

Curating Wairau’s first show is Nigel Borell, who is well known to many after the incredibly successful Toi Tū Toi Ora at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki — the show that gathered an extensive and landmark collection of contemporary Māori art together for the first time in decades.

“All of these moments are about timing,” Borell tells me. “The Hundertwasser Art Centre and Wairau Māori Art Gallery have been in the thinking, the planning and the fundraising since 2011 or even earlier. It’s also had various support from a range of donors — local and national government support, philanthropic support and private sector support — to get off the ground. Its potential is really exciting for Whangārei, for the north and for its community.”

For those who don’t know, the spectre of Austrian-born painter Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928– 2000) has haunted the north for many reasons. Hundertwasser lived much of the latter part of his life in Kaurinui: making art, extending himself beyond the alienations of his visitor status, and going out of his way to connect with local iwi at a time when no such ritualised engagement with Māori was normal or even expected, let alone from an Austrian deep-ecology advocate with a knack for surreal composition. Hundertwasser’s idiosyncratic relationship with the northern region of New Zealand may have appeared during his life to be an artistic eccentricity, but in its legacy it seems like an example of reciprocity and exchange with Indigenous communities, an alternative to the settler paradigms we know and loathe.

Before declaring Hundertwasser a Nobel laureate let me be clear: I cannot say if Hundertwasser’s hold on the north, and the very present legacy of his brand, is objectively good or bad for Māori. I am, however, pained to interrogate whether his imprint conflicts with the aspirations of Māori in the region today — and if so, whether Wairau’s existing so intimately with the finished Hundertwasser site presents an obstacle or an opportunity.

The Building. Photo by Greg Hay

“It’s the Hundertwasser Art Centre and the Wairau Māori Art Gallery,” says Borell. It’s the collaboration between the two that he is most excited about. “It’s actually a partnership between the Wairau Māori Art Gallery, the Hundertwasser Art Centre, and the Hātea Art Precinct. But most definitely Wairau gets to have its own space, has its own trust, and is governed by that trust in terms of having its own aspirations while working with those other partners towards a wider offering for arts in Whangārei and the north, and for us nationally.”

There is reason aplenty to celebrate a public space looking to platform contemporary Māori art. But the gallery calling itself “the first public gallery of contemporary Māori art” brought its own complications. “It got a bit tricky online a couple of months ago where people were being quite critical, saying, ‘It’s not the first Māori art gallery’ — and it most definitely isn’t the first Māori art gallery — but it’s the first publicly funded Māori art gallery. Its remit is for Māori artists and Māori curators being allowed to lead the way in terms of their own storytelling and the ways in which Māori art and aspirations are made visible. That’s how it’s distinguishing itself as a gallery.”

The fact it’s taken so long for something like Wairau to be funded and green-lit comes as no surprise. The cynical might agree that though we seem to be in a climate where galleries are buttressing their funding applications with token gestures of diversity and ‘affirmative action’, the deafening absence of permanent national spaces for Māori art (outside the peddling of touristic exhibits) should speak for itself. But this inhospitable ambience doesn’t deter those involved with the Wairau project from continuing despite this problem, with Wairau a significant stepping stone — perhaps not in spite of, but in partnership with, the Hundertwasser Trust.

The question of Hundertwasser’s legacy, his intentions for the north, and where Māori exist within that framing — which for the Hundertwasser Trust succeeds as a viable business model — leaves a grey area that’s as murky with doubt as it is promise. Doubt, because no matter how nice it might be to conceive of a world in which Wairau or a gallery like it could happen independently, we are just not there; promise, because being able to seize opportune moments amid settler bureaucracies is an age-old strategy, one which can be successful not just for Māori but for any marginalised group with an eye to survival. Perhaps Hundertwasser understood this more than we give him credit for. He insisted, for instance, that the project’s Māori component was key and should be autonomous.

“I sometimes wonder if it’s easier for a migrant to do something like that,” says artist Ngahuia Harrison, Wairau’s youngest board member. “You have a separate attachment to the legacy of colonisation, so perhaps there’s none of that inherent guilt or anger when you come in fresh. You’re afforded an objectivity that perhaps Pākehā don’t have.”

“Even on Hundertwasser’s original design he always wanted a Māori space in there,” says Andrea Hopkins, Māori artist and Northland local. “Hundertwasser wanted a space that was of both national and international standard, that was devoted to contemporary Māori art. He didn’t want to overrule or have rein on what went in there, just that it was a Māori art space. That was the conception of Wairau — separate but integral.”

Hopkins doesn’t just come from the perspective of a Māori artist, but of a local concerned with the systematic denigration of the arts in her region. Efforts to correct this could help her career, but also tap into the neglected reserves of talent around her. Historically, Ngāpuhi and regional communities broadly have been treated to a strategic starvation of institutional and infrastructural support which on global measures we’d recognise as active ghettoising. Arts infrastructure is no exception. “The creative community isn’t valued here,” Hopkins says. “They just ripped out all of the mainstream arts programmes at NorthTec [polytechnic]. Those people who ran for council when the centre was first getting built, using ‘Say No to the Hundertwasser’ — imagine basing your entire political campaign around saying no to a public arts project. Come on, Whangārei! That mentality is why a lot of people leave.”

The opposition Hopkins references has been an ongoing saga. For those readying the way for Wairau, it’s been a sharp and prolonged headache — headwinds that slowed what could’ve already been an up-and-running national asset with international leverage. The voluble naysaying saw a strategic playing-off of Wairau against a neighbouring cultural centre, Hihiaua. Despite the two having separate (arguably complementary) agendas, they were pitted as oppositional.

Though arts-adjacent, the Hihiaua Cultural Centre focuses on community more broadly, drawing from outside the conventional networks of the art world — an approach which has seen it garner almost unanimous community support.

“It’s a very dynamic space,” says Janet Hetaraka, secretary of the Hihiaua Trust. “What we do here is provide a few resources, the place and environment for people to be able to bring and share — our working ethos is to reclaim what’s ours, restore what’s broken, renew what needs to be renewed. Reclaim, restore, renew. That’s very meaningful to us when we break it down, because a lot of people have lost their ability to be deeply rooted in their culture — and for us, that’s been the most beautiful thing, seeing people reclaim, restore and renew for themselves.”

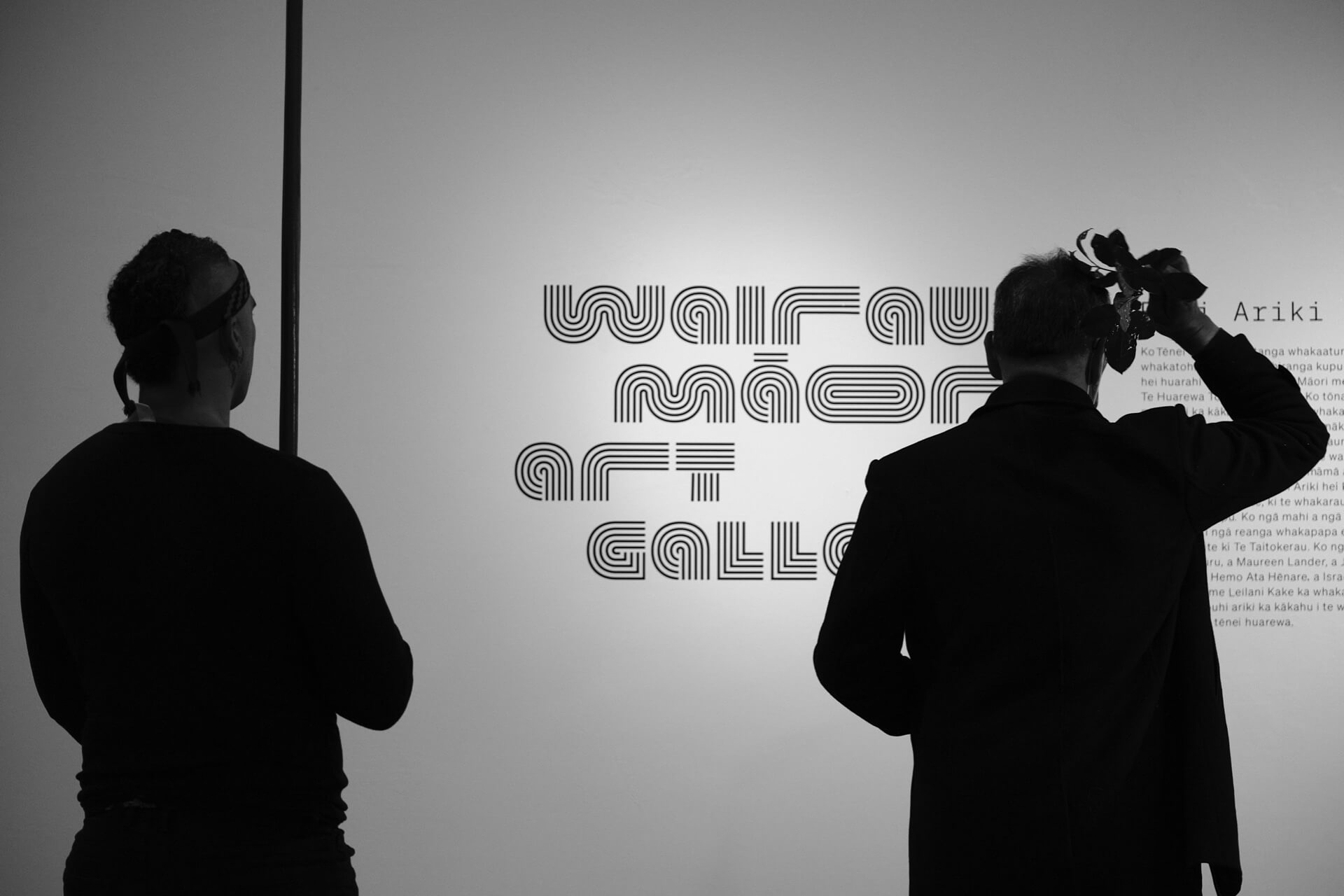

Installation photo from the opening show.

The Hihiaua Cultural Centre sits less than a kilometre down the same riverbank as the Hundertwasser building, with the Whangārei Art Museum making a convenient midpoint — essentially they form a unique triumvirate. Though each has its own agenda, these are anything but opposed. “We have a team that’s spread across both spaces,” says Simon Bowerbank, current head of curatorial and engagement at Whangārei Art Museum (WAM). This is unsurprising considering their physical proximity. But it’s more than a camaraderie: due to the political difficulties of funding, it’s a necessity. What makes the area’s emergence as a crowded arts precinct more exciting is how historically standalone WAM has been. “Until now, the Whangārei Art Museum has been the only public art gallery in the whole of Northland, which is a huge region for such a small gallery to service.”

For both Hihiaua and Wairau (and the wider precinct) the fiction of their animosity has been a disappointing hurdle, twice damning considering that they share a whakapapa. A massive opportunity was tarnished by deliberate misinformation — as of this political moment, nothing new — and the short-sightedness of a community which can only benefit from something like Wairau. A lot of the misinformation had to do with funding, coming to a head during the 2015 referendum that ultimately approved the Hundertwasser project. Claims were made that the bulk of the funding for the Hundertwasser building was to come from ratepayers, when in reality this amount was fractional. Regardless of what sectors (or individuals) these claims were coming from, they raise the question — in what universe would a space committing itself to the platforming of Māori artists, while giving Māori complete autonomy in that space, ever be a detriment?

In clearing up misgivings locals might have about Wairau and its trust (previously a Māori advisory panel), they need look no further than Elizabeth Hauraki and Elizabeth Ellis, both members of the Wairau board. Ellis is chair; Hauraki is treasurer. “The concept arose in 1988 when Hundertwasser first approached the Whangārei council,” says Hauraki (affectionately called Liz-Ann by board members to stave off confusion between the Elizabeths). “It didn’t go anywhere then, but it was resurrected in 2012 based on Whangārei District Council wanting to build the Hundertwasser. I had just finished the Auckland Art Gallery development project when they approached me for the Māori advisory panel with Elizabeth Ellis as the chair — so we as a team have been on this project since 2012.”

Ellis and Hauraki have seen the evolution of the advisory panel to the Wairau Trust as one of refining Māori agency; of taking the project’s focus on Māori and Māori art and finding an independent position — and the options which that independence affords — within a global network of institutions. (The main Hundertwasser base is in Vienna.) Beyond this, they envision an opportunity to connect with global Indigenous histories and communities. “Māori artists across the country have got relationships with other nations,” says Ellis, “including relationships with other Indigenous cultures, particularly strong through Canada and the US. For example, there are exchange residencies where Māori go to Evergreen State College in Washington state and make significant art there with Indigenous people. Through that relationship we could show their work in our gallery, of Māori and Indigenous artists from around the world. It’s a really exciting prospect. There’s a parallel universe — one is mainstream, and the other is made up of Indigenous people, our cultures, our histories, our stories — and that’s a link we’d like to make.”

Hundertwasser’s location in Whangārei is made more significant by the fact that Northland is essentially the birthplace of Māori modernist painting. “There was a whole movement in the 50s, from the marae arts which all Māori work was based on, to the contemporary,” says Ellis. “Art historian Jonathan Mane-Wheoki wrote about it happening in the north. It was actioned through the Māori art advisers, and they were all employed — Ralph Hotere and the like — to go around the schools of the north to encourage the making of Māori art, motivated by concern about what was happening to our culture. So those people made the transition, created the bridge between marae art and the contemporary Western arts happening in the day.”

On the rumoured tension between Hihiaua and Wairau, Ellis is breezily dismissive. “We met with Hihiaua and talked to them and it was wonderful, because we are all related through whakapapa. We consolidated and confirmed our relationship with Māori, reiterating that nothing else matters. It’s our relationship with each other that matters. We’ve sensed the tension between our two groups. That tension is not there any more. We already knew we had this throughline, though it had been fractured for some time.”

It’s something of a relief that Ellis and Hauraki aren’t deterred by a vindictive political strategy, that their vision remains intact. Because, as they describe, they have bigger plans. “The next phase of the project is huge,” says Ellis. “I call it MAMA, the Māori Art Museum of Aotearoa. We’ve got the title, but we haven’t got the funding.” She laughs, but not cynically.

A formal Wairau collection is already in the works, consisting of two Ralph Hotere paintings which will feature in Wairau’s debut show, to be stored at Whangārei Art Museum until plans for MAMA can be realised. Such ambitious, long-term plans show the embattled strength intrinsic to Māori.

For Ellis and Hauraki, Wairau’s potential to connect Māori and Māori artists with Indigenous populations overseas, who have meaningful exchanges to make concerning their shared experience surviving empire, is exciting — a worthwhile endeavour. Especially at a time when Western precepts seem exhausted, heading towards extinction and requiring renewal beyond the strictures of a global pandemic.

Even with Covid-related urgencies, the Wairau focus is one of hope — a hope to transcend its regional limitations and bolster the position of Māori, even beyond the arts. Arguably, this is the value of art when any governing body prioritises it — a stronger national identity by which to navigate an increasingly global world. Covid, for example, is a global problem with local symptoms which needs an imaginary comprised of both global and local mechanics for an effective solution. Similarly, climate change is a world-scale problem but which will be felt with harrowing intimacy (and in many parts of the world already has been) at a neighbourhood level. The solution is not a fetishised localism but a contingently broad strategy which can marry normally closed disciplines and coordinate beyond their insularity. It is the arts that are capable of taking

this god’s-eye view, able to fuse elements which wouldn’t normally leave their semantic boxes.

For Wairau’s thankfully petit naysaying cross-section, this should be food for thought.