Mar 21, 2024 Arts

When it comes to stolen treasures, Grand Theft Auto has nothing on museums. All over the world, in the past few hundred years, archaeologists have dug up ancient artefacts, rediscovered buried cities and plundered treasures that belonged to ancient civilisations and, indeed, the current locals. They made off with this loot in carts, trucks and sailing ships and it almost never went back.

After both world wars, soldiers returned home with suitcases full of stolen treasures. They didn’t care where the artefacts came from — they were souvenirs of the trade and the day, spoils of warfare. The movement of troops across the world let loose a thousand amateur Indiana Joneses, dashing graverobbers cosplaying as archaeologists.

And these stolen items, once ‘acquired’ and hoarded by museums, are often stolen again. In August, it was reported that an estimated 2000 artefacts — largely gold jewellery and gems from antiquity — were missing from the collection of the British Museum. The museum had ignored at least one warning from a dealer who’d contacted it years earlier, saying they’d been offered (and in some cases actually bought) pieces that they suspected had been stolen. It was revealed that although the museum had been in possession of these priceless heritage items for 200 years, they had never been formally catalogued.

Easy come, easy go, I guess.

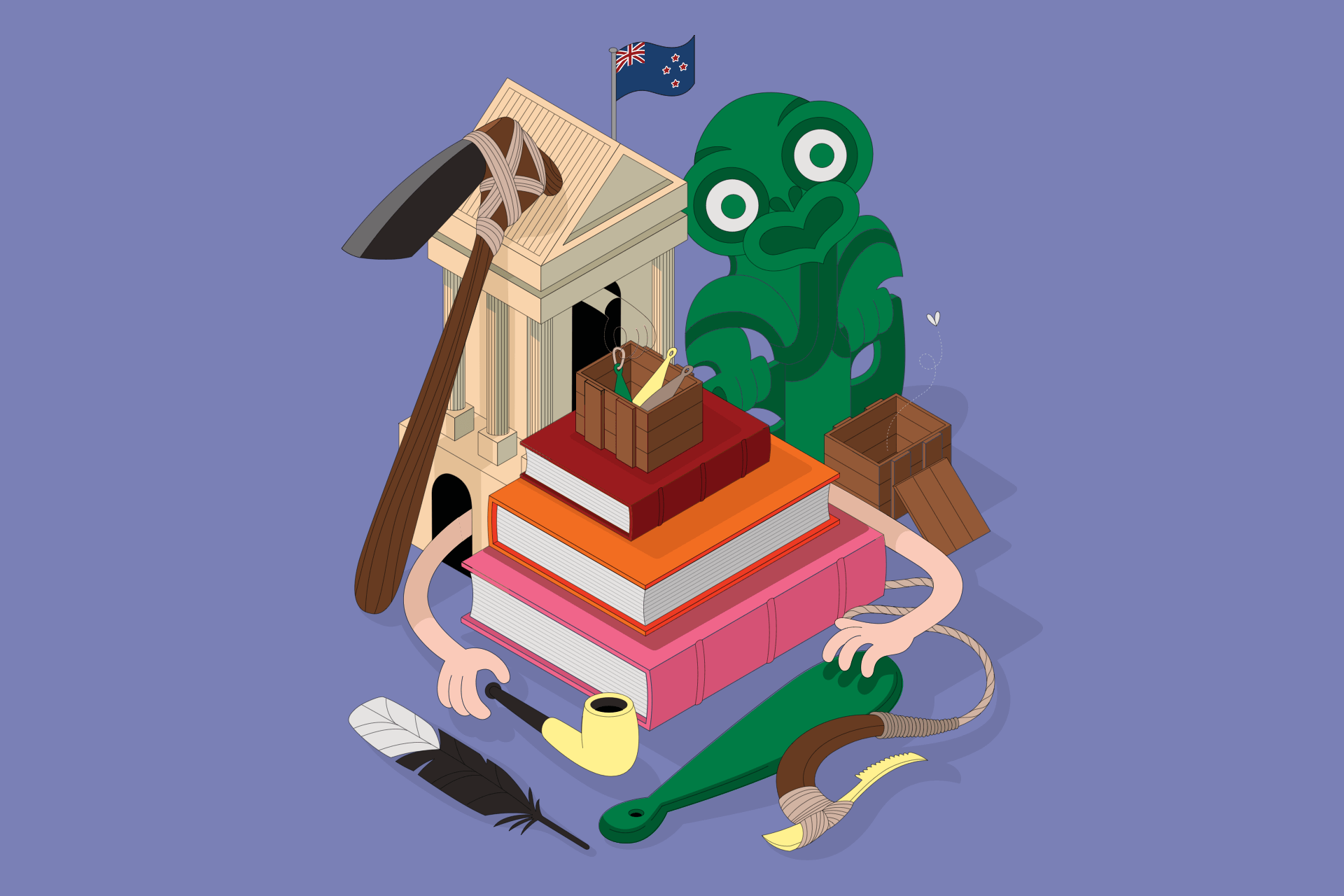

The first incarnation of Auckland Museum was established in 1852 by merchant John Alexander Smith in a small cottage in Grafton Rd. Announcing the museum’s opening to the public, Smith as honorary secretary stated:

The object of this Museum is to collect Specimens illustrative of the Natural History of New Zealand — particularly its Geology, Mineralogy, Entomology, and Ornithology. Also, Weapons, Clothing, Implements, &c., &c, of New Zealand, and the Islands of the Pacific. Any Memento of Captain Cook, or his Voyages will be thankfully accepted. Also, Coins and Medals (Ancient and Modern.)

Smith was successful in wheedling donations and loans from upstanding residents of the colony, recording them carefully in a journal. After an ambitious start, Smith moved to Napier in 1857 and the museum fell into abeyance. A decade later, the fledgling institution was adopted by the Auckland Institute, which found it a purpose-built home on Princes St, opposite the first Government House, in 1876. From there, as the Auckland Institute and Museum, it developed one of the great collections in New Zealand, including specimens of scientific significance, Victorian artworks, a small library of books and a huge number of Māori taonga.

A jubilee book from 1917, The First Fifty Years of the Auckland Institute and Museum and its Future Aims, records these fascinating years of growth. The members of the institute were mostly wealthy, well-connected Auckland businessmen, and in 1872, they helped secure two important collections of Māori carvings, the Spencer Collection and one made by the Marist Brothers. These were catalogued but unfortunately the artefacts weren’t strictly supervised; over the next 10 years, major parts of the collection slipped quietly away.

Still, the Auckland Institute and Museum continued to acquire. Four decades after opening on Princes St, the small museum was bursting at the seams with taonga, scientific works, statues, plaster casts, Japanese porcelain, ivories and bronzes, and boasted 100,000 visitors a year, even as Auckland at the time had a population of only about 130,000 inhabitants. The scholars of the 19th century were obsessed with the new sciences of medicine and the natural world, and collected prolifically. Amateur ethnologists were even hotter on Māori artefacts, using dubious methods to acquire them. The now-impressive collection of Māori adzes, cloaks and greenstone and stone implements was stored in wooden boxes, offsite and out of mind.

It was the largest museum in New Zealand, but had outgrown its home and was about to get even larger. The search for a new premises was intense, helped by a bequest of £1000 from Sir John Campbell after he died in 1912. The original idea to create a massive new building along Eden Cres and Princes St was finally abandoned in 1918 in favour of a site on the tuff ring of the old Pukekawa volcano — ‘the hill of bitter memories’ — in Auckland Domain. The new Auckland War Memorial Museum, opened in 1929, was a monument to the fallen of World War I, but in its size and grandiosity felt almost like a tribute to or glorification of war.

The site, then known as Observatory Hill, was within two miles of the central Auckland Post Office — it was intended that taking a tram from Queen St to the museum would be a nine-minute trip. The expanded museum now had space for more of its collection; many numbered pieces, recorded in massive ledgers, were retrieved from their storage and put on display.

In his excellent book A Good Place to Be: Auckland Museum People, 1929–89, Ian Thwaites diligently records the dedicated directors and knowledgeable curators who managed the collections, events and lectures that made up one of New Zealand’s finest scientific and cultural institutions. The museum was a cornerstone of New Zealand culture, with extensive, well-beloved displays and the remainder of its collection housed offsite. Many Aucklanders can nominate a favourite object or two, images of which became seared into their memories after many repeat visits. And from reading the careful, authoritative labels affixed next to the exhibits, those Aucklanders probably thought the objects off display were being looked after by the ‘museum people’ with equally authoritative care.

In the mid-1980s, New Zealand Steel commissioned world-famous New Zealand-born photographer Brian Brake to photograph Auckland Museum’s collection of korowai for a glorious calendar and book in conjunction with the exhibition Te Aho Tapu (‘the sacred thread’). Brake, who was known to the museum and had photographed the sensational Te Maori exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1984, set up his camera in the basement of Auckland Museum. Renowned for his sensitive lighting of objects, Brake had no problem getting permission to photograph the famed collection of cloaks and take his time over it.

I had the advertising account with New Zealand Steel at the time, so I attended some of the sessions with Brake. He was pleased that the museum had given him access to hundreds and hundreds of boxes, carefully labelled as to contents and source. But Brake was also amazed that so many of the boxes were empty. Opening a crate, he would often find just a few drifting feathers, or nothing at all. Patu and cloaks, priceless objects, were missing from boxes that were specifically labelled as such. Where had they gone?

More than three decades later, I arrive at Auckland Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira to ask the new tumu whakaere chief executive, David Reeves (who first joined the museum in 2011), about the missing items. Reeves acknowledges that taonga disappearing was an issue in the past. He doesn’t, however, believe the problem was widespread — telling me he understands that in the 1980s, some cloaks had been found to be missing, but that the number was fewer than 10.

In 2018, Reeves says, the museum’s full collection was catalogued and recorded — a major undertaking (and something the British Museum has yet to do). He says he’s proud of the job and that there’s now a full, accountable record. The recent news about the British Museum’s losses, Reeves tells me, stunned the museum world. It turned out to be the work of an insider, a long-time curator who was fired earlier this year and is now under investigation by the Metropolitan Police. The curator even recently visited Auckland, supervising the hugely successful Ancient Greeks: Athletes, Warriors and Heroes exhibition in 2022.

Though the museum world might claim to be stunned, and the affair led to the resignation of British Museum director Hartwig Fischer, how unusual was the behaviour of this curator and the failure of the museum systems to catch notice the thefts?

In 1997, I was in New York visiting the United Nations and took some time off to see the city. On 2nd Ave, I stopped at an upmarket gallery selling African art and antiques, all very expensive, of course. Working away on a massive work table was the renowned American photographer Peter Beard, who was preparing a series of large prints taken in Africa for a forthcoming exhibition in Paris. In true Beard style, he was smearing the black-and-white prints with both his own and animal blood.

More unusually, Beard was bandaged and clearly in pain. Not long before, he had barely escaped death, he told me, when he’d been charged and crushed by a rogue elephant. We fell into a conversation about Africa and the exploits of Ed Hillary. He asked me to go buy him a couple of bottles of vodka from a nearby store. When I returned with them, he worked, I talked, and we both got slowly drunk. Around six o’clock, the gallery owner came in to close up, and asked me to join him and Beard for dinner. When I told him I was from New Zealand, he said he had a few rare things out the back I might be interested in.

In the storeroom, he opened three large boxes. Inside each box was a very fine Māori korowai, in perfect condition. Two of them he’d had for at least five years and he’d lined up buyers for them — not American, but “international”. And the tags on the old flax shoulder ties, with perfect inked handwriting, were the same brown labels I remembered from Auckland Museum. I instantly remembered the Brake shoot, but said nothing.

There are more stories. Jim Foley, a jazz pianist who was well known in the Auckland rag trade in the 1950s, had a collection of Māori carvings in his home at Waiatarua. His wonderful architectural house looked east towards Auckland city. Inside, it housed two large pou whakairo: one had been dug up by local enthusiasts from the Te Henga swamp; the other, Foley said, he’d been ‘gifted’ by Auckland Museum. He had taken his swamp carving to the museum for restoration and been told they couldn’t help, but they did have a similar one he could have to match. Sadly, Foley’s huge collection of artefacts and records, including the two carvings, was later destroyed in a fire.

In the 1960s and 70s, I was acquainted with a well-known Aucklander who had worked at the museum as an assistant in his student days. He had acquired a sizeable collection of adzes, which he’d ‘found’ in large numbers in cartons in the basement. I inferred he’d simply pocketed them on his tea breaks.

One Auckland businessman in the 1970s kept in a glass case in his office a superb collection of ancient oil lamps and colonial pipes. Their provenance? Auckland Museum, which seemed to be a supplier of note and purveyor of favours to its friends and connections. I recall being concerned about these ancient treasures — surely they belonged to somebody, somewhere — but there was no guilt or remorse forthcoming from their current private holders. The idea, I gathered, was that the museum was simply unable to store and care for its more than 100,000 items. Some went west informally to relieve pressure on storage space; over others, insufficient guardianship was being taken and opportunists popped up to take advantage.

A few weeks ago, I had coffee with Gordon Maitland, former curator of the pictorial collection at Auckland War Memorial Museum. He came to the museum library in 1975 and held a number of positions thereafter; I always found him the most helpful photographic librarian I had ever dealt with. A photographic archivist, Maitland, by the time he retired in December 2013, was one of the museum’s longest-serving staff members and a great favourite with the public. His knowledge was encyclopaedic, and he gave regular lectures on the museum’s photographic collections.

I asked Maitland about his memories of theft from the museum. With a wry smile, he told me about the time a well-known professor bequeathed his huge library to the museum. At first, Maitland was delighted when all the boxes arrived, then dismayed as he realised that many of the books were already stamped as “Property of Auckland War Memorial Museum Library”.

A little later, my investigations into the ‘lost’ items of Auckland Museum took me to Puketutu Island, the home of Te Warena Taua, a kaumātua of Te Kawerau ā Maki. Taua was the first Māori ethnologist at the museum, starting there in 1984 and staying for 12 years. He was more than pleased to give me some context about the issue I was looking into.

During his time at the museum, Taua was kaitiaki for the 51,000 items in the Māori and Pacific collections, and remembers the wood and fibre artefacts with great respect. He explained to me the three ways the museum acquires taonga: by deposit, gift and purchase. Depositing might be by an individual or a family; much like money in a bank, objects can be withdrawn at any stage by direct descendants of the whānau. Gifting comes free, without any obligations on the museum, which will then record the artefact, catalogue it and own it. Finally, purchase is where taonga are bought by the museum for a price. Taua says he attended many auctions on behalf of the museum, and always had a clear budget with which he could bid for works.

He is clear that as well as this flow of objects into the museum, existing collections were borrowed from. Without doubt, he says, there was a flow of objects out — as ‘gifts’, their removal overseen by a well-known staff member — that exceeded all bounds of appropriateness. This person held a high position in Māori and Pacific collections, and took it upon themselves to decide that cloaks, mere and carved wooden taonga could be ‘gifted’ away from the museum. They did so without fear of detection or censure.

Taua is still upset, angry, about what he sees as theft from a public entity, but back then he says he had no one to turn to. The collections at Auckland Museum are of huge importance to future generations, and curators had a clear duty of care over them — even more so given the ruthlessness and ethically dubious methods by which some items within them were acquired in the first place. Yet they were being significantly raided by an insider. This person may have felt at times that they were doing the right thing — returning an object to a rightful owner — but many of the gifted objects were given as favours, rewards, to leaders in the community whom he felt had been kindly inclined to Māori and Pacific causes.

I spoke with Taua about the histories of other taonga gone out of reach — such as the artefacts taken by various governors-general of New Zealand. Some of these office-holders returned to England with not only thousands of bottles from the Government House wine store but also Māori treasures gifted to previous governors-general on tribal visits or to mark major Māori events. The cloaks of honour that were put around their shoulders were not returned, or offered to museums, but taken as souvenirs of the day. Many of these priceless treasures now sit in dusty cupboards in historic mansions in Britain — their mana and mauri disrespected, their connections to Aotearoa severed. George Vere Arundell Monckton-Arundell Galway, the 8th viscount, who left New Zealand in 1941, or Charles John Lyttelton, 10th Viscount Cobham, in office from 1957 to 1962, come to mind as governors-general who were well rewarded with souvenirs of significance. Some of their descendants, thankfully, are returning these gifts, but many treasures are lost forever. Taua said he is proud to have overseen the return of taonga to their original iwi and hapū owners and continues to do so whenever he sees the opportunity. But such returns and repatriation must be handled openly and correctly, or further injustice risks being done.

Across town, I turn my attention to the Museum of Transport and Technology, MOTAT. I seek out Judith Tizard, who at one time in the mid-2000s concurrently held the roles of Minister for Auckland, Minister Responsible for Archives New Zealand and for the National Library, and Associate Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage. Tizard is a tireless advocate for MOTAT and enthuses to me about its success as a tourist destination, the recipient of thousands of machines and locomotives.

The museum was set up at Western Springs in 1960, around the historical Western Springs Pumphouse, and opened in 1964. Its establishment was driven by a combination of groups, with a core of amateur engineers, transport enthusiasts and garage restorers; it became a type of public workingman’s shed. According to Tizard, within two years MOTAT had 4000 volunteers. Half of Auckland seemed to have emptied their garages and sheds and donated the contents — lawnmowers, vintage cars, washing machines and piss pots — to the new museum. Quickly MOTAT acquired more than 100,000 items and its volunteers were overwhelmed. The museum had nine staff at the time, who went through the enormous amount of donated material. Every week, they seemed to acquire half a tonne of machinery, often in pieces and in serious need of repair. The site became littered with rust, decay and chaos.

Initially run by an incorporated society, MOTAT gained some funding from Auckland City Council in 1984 — Judith’s mother Cath Tizard, another great supporter of the transport museum, was mayor at the time — and formalised its structure under a director and board of trustees. Later, Judith Tizard was integral in pushing for the Museum of Transport and Technology Act 2000, which saw the institution become regionally funded through a ratepayer levy across the whole of the Auckland region. Today, we still help to pay for MOTAT and Auckland Museum via our rates.

Tizard and I talked about how the junk piles became the basis of the successful entrepreneurial museum of today — but also about how, along the way, the MOTAT collections became at times a sort of ‘swap meet’ for the volunteers. Someone who specialised in Model Ts, for example, or ancient milking machines and wanted a part might seek out a volunteer skilled in and passionate about such a device. They’d help you find the correct shed and pick out your part — for the greater good of repairs, of course. It was not sustainable. Legend has it that volunteers enthusiastically gave away a whole donated fire engine to an enthusiast; it took two years to find the appliance again, and when recovered, it was in 400 pieces.

In 1994, the original Mr Fix-it, Grant Kirby, arrived to sort out MOTAT, as its new director. He had been with Auckland City Council since 1968, finishing up in 1993 in charge of a wide range of city services, and had been an enthusiastic visitor to the museum since the 1970s. Kirby made progress at getting the blokes in sheds organised, and focused on restoring the trams, buses and cars that were mounting up (they just kept coming as their owners aged and died). He brought a degree of professionalism to the institution while retaining its volunteer charm.

But even this former MOTAT insider knows the pain of donating an exhibit only to see it disappear from the collection. Kirby told me that when he retired, in 2000, he gifted his beautifully restored Morris Minor and glorious Fleetwood Cadillac to the museum. A year later, he saw the Cadillac in a Webb’s catalogue, up for auction. Obviously MOTAT can’t keep everything, but it’s hard to see a cherished object liquidated for cash. It’s been hard, too, for Kirby to observe the full changing of the guard at MOTAT — from volunteers to professional museum workers — but one hopes that these curators now keep a tight eye on the precious mechanical objects that remain.

A few levels down from Auckland Museum and MOTAT, there are many other small local museums, enthusiastically run by local volunteers. Researching this story, I toured many and asked the museum workers if they ever lost items. Nearly all agreed they had. Maybe they’ve just been borrowed by the odd collector, they said, thinking of crockery and small ornaments. But they also all told me: We have taken our Māori artefacts such as adzes and wooden carvings off display; otherwise, they simply vanish.

I could sympathise with their losses. Some time ago I gave my own small collection of traditional Māori fishing implements — picked up here and there at auctions, or given to me as gifts — to a certain museum which will remain nameless here. I thought I was doing the right thing by passing them to the museum to care for and for others to see (when objects are untethered from their original rohe and owners, it’s hard to see which iwi or hapū they should rightly be returned to). But while writing this story, I decided to check in on them and discovered that, like so many other taonga I learned about for this story, my gifted items had vanished — gone with the wind.