Sep 19, 2016 Theatre

Stand-up comedy, song and sketch are all vehicles through which Hayley Sproull explores what is means to be a white, disconnected Maori descendant, in her new show Vanilla Miraka. Ahead of opening night, Sproull describes the inspiration for the work via her family photo album.

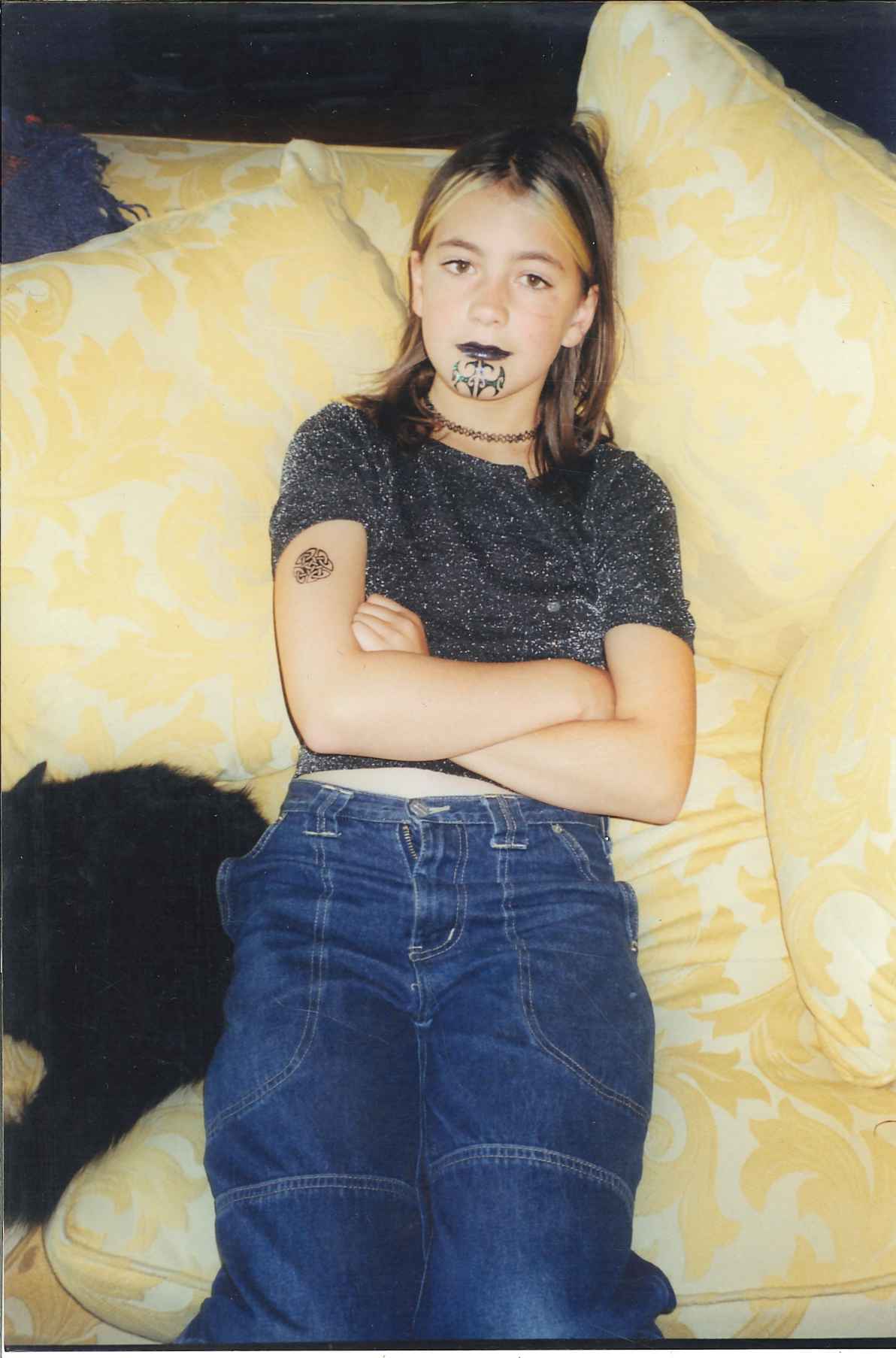

This is me in 1999 (left). I’d just been down at the local Eastbourne fair, where they were doing temporary Ta Moko. This particular moko was covered in glitter and I felt pretty good sporting it. You can tell how bad-ass I feel by the way I’m folding my arms, and by the way the fly on my skater jeans is down and I don’t even give a shit.

This is me in 1999 (left). I’d just been down at the local Eastbourne fair, where they were doing temporary Ta Moko. This particular moko was covered in glitter and I felt pretty good sporting it. You can tell how bad-ass I feel by the way I’m folding my arms, and by the way the fly on my skater jeans is down and I don’t even give a shit.

I’ve been claiming my Maori heritage since I was young. ‘I’m one-quarter Maori,’ I would boast as a kid, not knowing really what it meant, where it came from or why I thought it was important. But I knew I was proud of it, and I knew it was something special.

When I was 10, the primary school I went to was going to visit a marae on a school visit and they asked me to be the kaikaranga. I didn’t know what it meant, but basically I was the loud girl at school, and they needed someone loud. Merely a bonus that I was part-Maori. I happily accepted.

I worked hard with my Mum to learn it; practiced it for hours at home and even recorded it so I could critique my own 10-year-old voice calling a language I didn’t know back at me. I knew that thing inside out; I think I can even remember it now.

The day came for my moment of Maori glory. We stood outside the marae and I was ushered to the front. The words of my karanga were looping in my head when suddenly a powerful voice started screaming my way. Haere mai…haere mai…

Suddenly I was overcome. I burst into tears and ran for the bus, where I stayed for the rest of the visit. I don’t know who called back, I don’t know how they got on; all I know is that I didn’t want a bar of it. My dreams of marae stardom were shot and I would NEVER try again.

Suddenly I was overcome. I burst into tears and ran for the bus, where I stayed for the rest of the visit. I don’t know who called back, I don’t know how they got on; all I know is that I didn’t want a bar of it. My dreams of marae stardom were shot and I would NEVER try again.

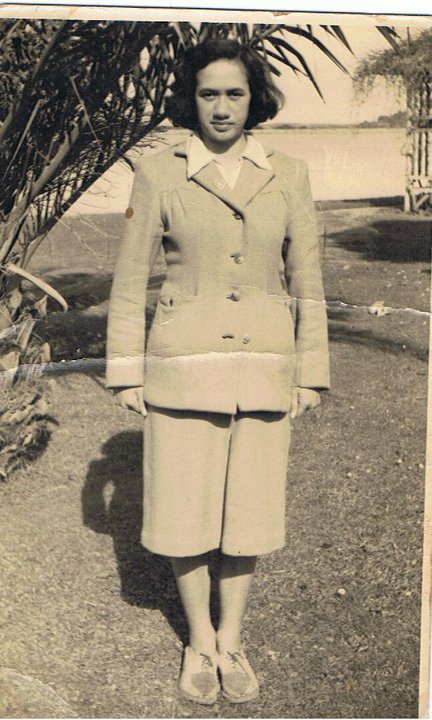

That pretty much sums up my relationship with my Maori heritage as a kid; my Nana (right) wasn’t particularly connected in her later years, so my family had just sort of…let it slip. It wasn’t until I was an adult that my curiosity began to crawl back, and I began to question what ‘being Maori’ actually meant.

Then my Nana died and it felt like that whole part of my heritage was even further from my reach. She was my strongest connection to that world, and when she died I felt that the connection was gone. I floundered my way through her tangi and when it was over I wanted to run. My displacement when encountering Maoridom grew; I had so many questions but felt that my ignorance, my anxiety and the milky hue of my skin meant I couldn’t ask.

The conclusion I came to in order to address this was to make a theatre show about it. Naturally.

Vanilla Miraka is a playful depiction of how I have struggled to feel allowed to be Maori. Told from the front line of my Nana’s tangi, it uses stand-up, song and sketch to explore the question of where I fit in my own culture. It sounds very serious. It really isn’t. I’ve always turned to comedy as a means of expressing what is really important to me, or what is hard to say. Vanilla Miraka aims to allow people to laugh at themselves through laughing at me, as I stumble, sweat, and sing my way through my whakapapa, with the simple goal of trying to get a little bit closer to who I am.

Vanilla Miraka: presented as a solo double bill with Banging Cymbal, Clanging Gong (which you can read about here); 20-24 September, Basement Theatre. basementtheatre.co.nz