Aug 23, 2023 Theatre

When Greg McGee’s stunningly original play Foreskin’s Lament — set in a suburban rugby changing room — opened the Circa Theatre in Wellington in 1981, it sent shockwaves through the country. Its brutal crisp raw dialogue, its nakedness, and its truth resonated with New Zealand theatre goers and it quickly was earmarked as a milestone for its observation of who we are and what we do and think. It attacked and revealed our true identity and would become a must see and for schools and universities a textbook reference for years to come.

It echoed the Springbok tour which had torn New Zealand apart dividing and separating who we are. It changed the face of rugby and masculinity in New Zealand forever. In October 1981, Metro talked to the young playwright Greg McGee an All Black triallist about his work and the outrage it had caused, the opening and its future. I think that neither realised how successful and important it would be on the New Zealand landscape.

Bob Harvey, The Archivist

–

It’s not quite a year since Greg McGee’s ”Foreskin’s Lament” was first performed at Auckland’s ‘Theatre Corporate. But in that time the play has excited more admiration -and abuse than perhaps any other indigenous work. Readers of ‘The new Zealand Times have been following a spirited debate between the writer, fellow playwright Bruce Mason and “community standards” campaigner Patricia Bartlett. Trish Gribben talks to Greg McGee ‘

Foreskin’s Lament

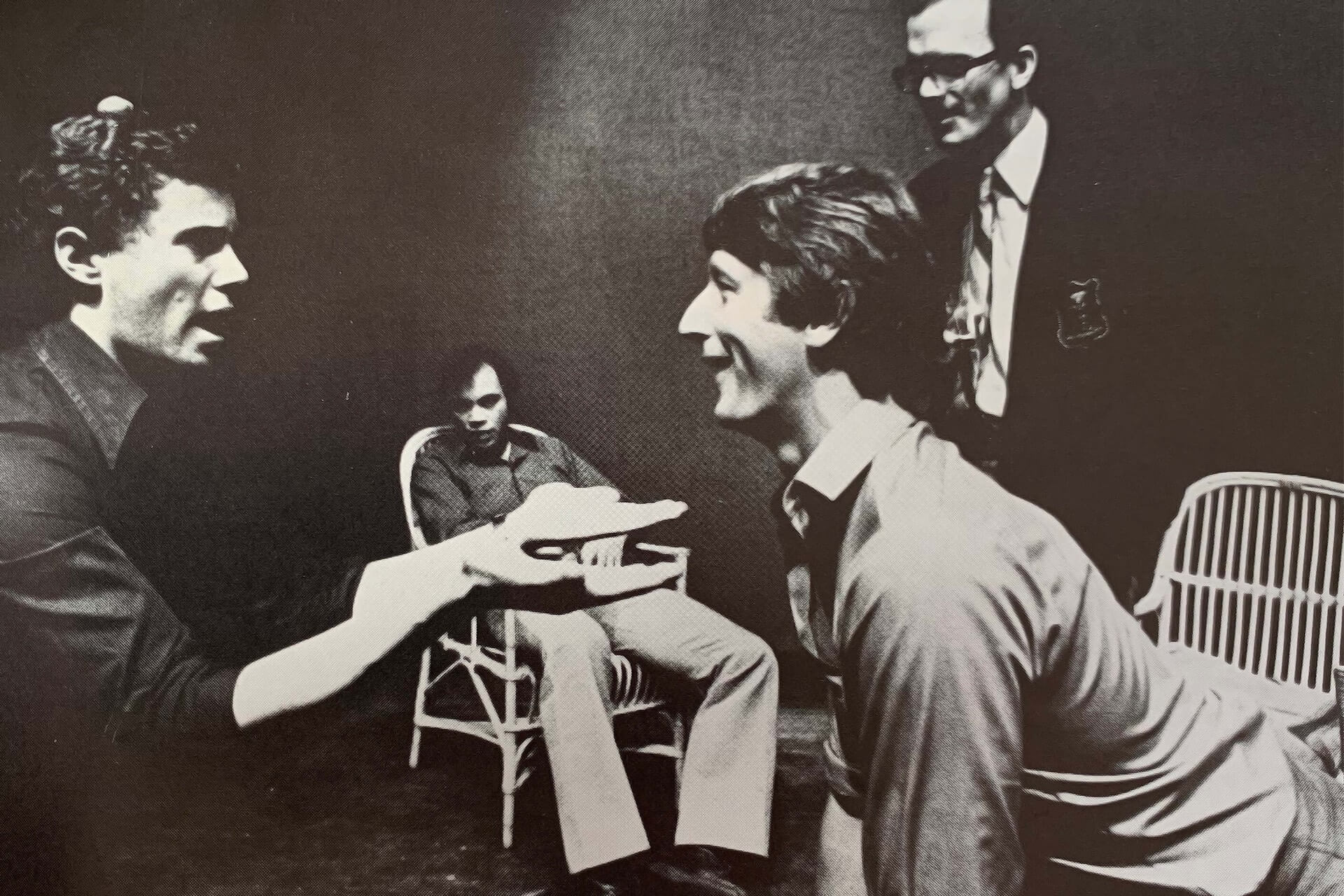

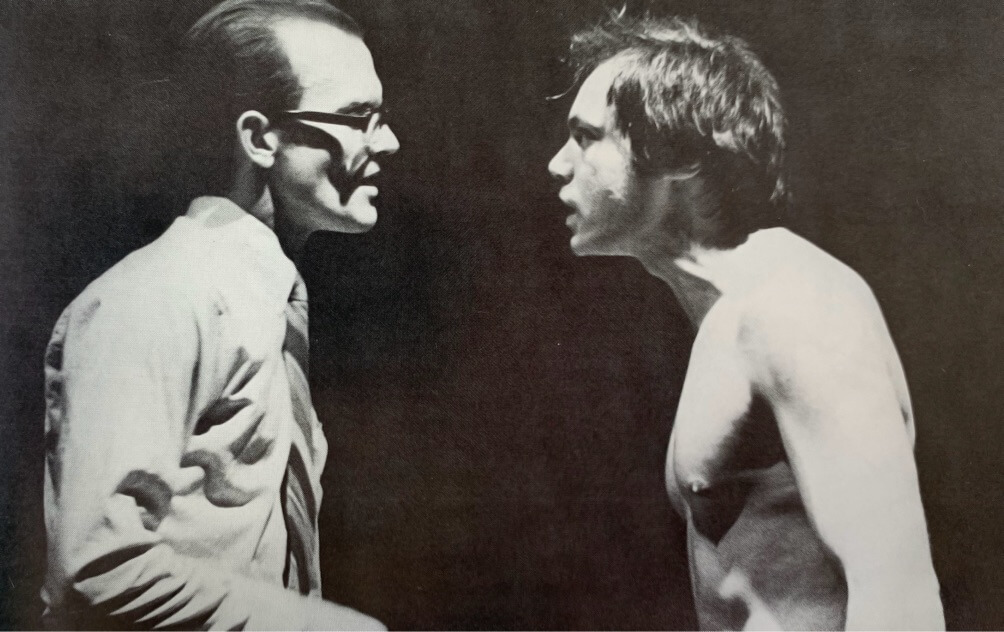

The audience sat stunned and silent in the blackout that fell on the first impassioned outpouring of Foreskin’s lament before the hush surged into wildly-cheering applause. That was at a session at the Playwright’s Workshop, held in Wellington in May last year. The word quickly went out: Here it is: Our Play. The first public performance of Lament was on October 30, 1980, with Chris White in the title role, directed by Corporate’s Roger McGill. Any doubts of over-reaction from those devoted to theatre at the Workshop were dispelled on opening night. There was the stunned hush, then a stamping, standing ovation that has become almost standard reaction throughout the country. There have since been sell-out and extended seasons at Palmerston North’s Centrepoint Theatre, Wellington’s Circa ( a production which later moved to the Opera house for a record-breaking run) and at Dunedin’s Fortune Theatre. The play opens in Christchurch this 88 Auckland Metro month. Court Theatre there is taking it straight to the bigger Theatre Royal for its season. Critic and dramatist Bruce Mason, reviewing the Centrepoint production, eulogised “the seething vitality, the prodigious virtuosity of the text itself, that quality by which all great drama instantly declares itself.” Mason went on: “It has been obvious to some of us for thirty years or so that ‘the great New Zealand play’, to call in that old chimera, would be about rugby football. This is it.”

Of course the play has touched raw nerves. Not all the uproar has been in admiration. Patricia Bartlett wanted to write to the Queen about its filth, foulness and nakedness. She was anxious that the Queen’s representative should not demean her title by seeing the play and hearing the obscene four-letter word which, Bartlett counted, appears in the text 53 times. (The Queen’s representative, Sir David Beattie, had only one word for the production he saw: “Brilliant”.) In Dunedin an irate and articulate citizen stopped the performance in its dressing room tracks with an outburst of his own, a diatribe on the slump of standards in that city that was of such a standard the audience wondered if it was a ploy in the dramatist’s plot. When the splenetic fury abated, the audience was asked if they wanted the play to continue. Applause rang out the answer.

Foreskin’s Lament is a play rooted in the mud and mores of Rugby in the Land of the Big Black Boot, but a play that reaches out way beyond the side-lines and goalposts to the rucks and scrums, sidesteps and rules that involve us all: As Michael Neil of Auckland University’s English Department says in the foreword to the published text; “What Greg McGee’s play has to show us is that it was never possible to keep politics out of rugby, because in New Zealand ( as in South Africa) rugby has been an expression of the polis “this is a team game son and the town is the team. It’s the town’s honour at stake when the team plays, God knows there’s not much else around here”. The humour of “Foreskin” is witty, dark and belly-shaking. The title (McGee has resisted pressures to change it to make it more palatable to the tweed jacket and twinset brigade) comes from the long literary lament with which Foreskin ends the play. It is a lament for those “who know their history by itineraries”.

It begins as a howl for a captain dead from a foul kick from his own side, moves into nostalgia for the dear departed days of wintry Saturdays (“for a whole generation God was only twice as high as the posts”) and mourns the inadequacy of heroes encountered in Foreskin’s other world – literary academia Neil writes: “The final litany of mourning sets the catechism of rugby against the rival creed of Foreskin’s education. Neither is enough; if one set of myths is discredited, the other seems borrowed and fraudulent.”

Ironically, the academics whose cerebral approach to life is one of the dilemmas Foreskin tussles with, have embraced the play and welcomed it without delay into their curricula. Students of Stage I English at Auckland, Victoria and Canterbury universities are studying “Foreskin” this year.

For a play that examines the myths and legends of Rugby to be first staged the year before the coming of the Springboks and the “Days of Rage” is extraordinary timing. How did it happen? More through a personal readiness to write than by deliberate clever intent. McGee doesn’t know why the idea for Foreskin came to him when it did.

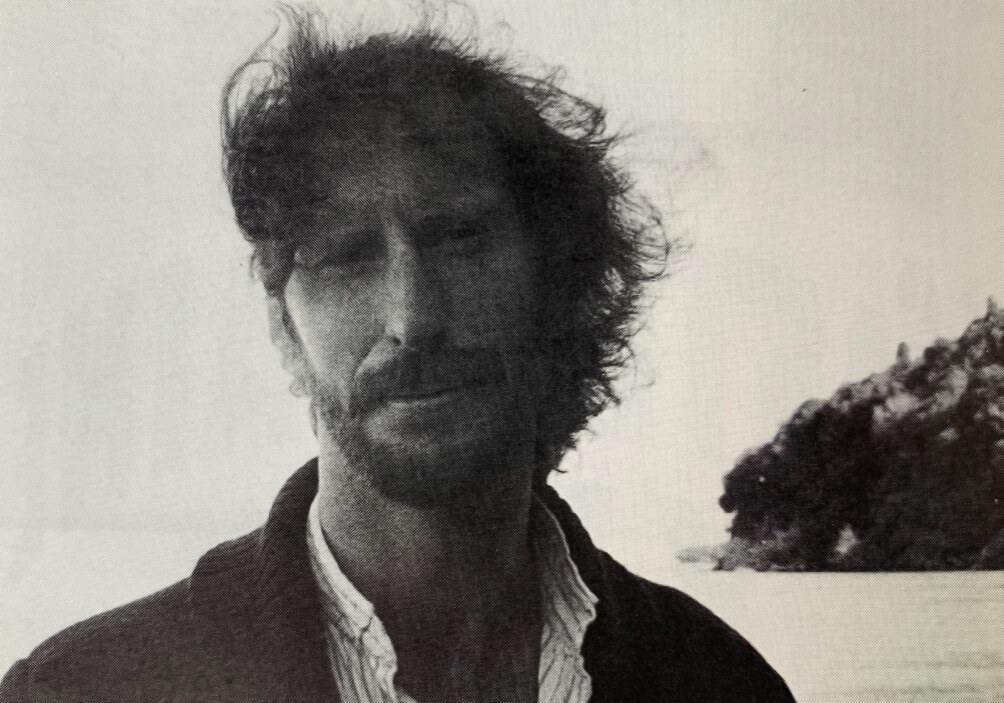

It was in June 1978. McGee had been away from New Zealand since 1975 a journey undertaken to extricate himself from the inevitable course of graduate student to law career. He was holed up on the North West coast of Sardinia where he comfortably fraternised the local fishermen, transplants from Venice since the days of Mussolini. After living in that canalled city, McGee could sing gondolero songs with the best of them. With the distance that gives a frame of perspective, McGee started poring over his past. “I’d tossed away a novel in London. Then on the beach set in a rocky coastline at Fertilia, I don’t know why, the idea for Foreskin came to me. I wrote the first scene and never changed it. I worked on old computer print-out sheets, salvaged from a job I’d had in London, wide enough to write the offstage directions down one side, the onstage dialogue on the other.”

Greg McGee by Shirley Gruar

That first scene opens in a rugby dressing room, strong evocative smell of liniment, mud, old socks, jockstraps, boots, balls, beer bottles and all. Offstage, Coach Tupper (“just an old fart left over from the Second World War”) shouts the first of his “kick-shit-out-of-everything” instructions to his team preparing them for the big match to be played on Saturday. “Let’s finish with a bit of guts – whaddarya anyway?” That is indeed the question and in Act Two, set at the beery after-match party Foreskin picks it up and shakes it until his despairing cry ends the play.

McGee kept notes through three months travelling through the States and arrived home for Christmas, 1978. Having manipulated my life to make time to write, it wasn’t in fact till I returned to New Zealand four years later that the work really took shape.” Three drafts were written during 1979 and late that year the play was submitted to Judy Russell of Playmarket for the Playwright’s Workshop. It was accepted, and its reception created ripples that are still widening.

Schooled by coping with a success of another social order as a 19-year-old Rugby player for Otago, McGee is reluctant to talk about himself. Aware of the gap between image and subject. He prefers attention focussed on the play, on his published, acted words and their message rather than on what might flow to be fixed in print for a media conversation. The biographical bones are skeletoned on the cover of the text of “Foreskin”, even in bare outline revealing the too-obvious-to-be-true similarities with the title character: “Greg McGee was born in Oamaru in 1950, and educated at Waitaki Boys’ High School and Otago University (LLB. 1973 ). He writes with special authority about rugby: He played for Otago; for South Island in 1970; for New Zealand Universities in 1971 and 1973; as a Junior All Black on the 1972 tour of Australia; and he was an All Black trialist in 1972-73.” He now works three days a week as a lawyer in Auckland leaving himself time to write.

And how did he happen on that name, “Foreskin”? Gee is reticent about all its origins. It was, in fact, a teammate’s nickname, chosen and retained for the aptness of many facets of its meaning. Seymour is called Foreskin, not only as a symbol of sensibilities cut off through choice by parents and custom early in life, but also because, as a physically and intellectually talented individual, he’s waiting for the chop – for the clobbering machine that reduces such upstanding figures to average size. Foreskin and his team mates, names as Bruce Mason points out, like the characters in a mediaeval morality play – Mean, clean, Tupper, Irish – have extended the reading out begun by Roger Hall’s Glide Time bureaucrats to drag whole Rugby teams into the theatres. As Roger McGill of Theatre Corporate says: “We had more of a cross section audience reacting to Foreskin than ever before. We had an audience of Rugby players we’ve never seen before or since.”

Foreskin is not an anti-rugby play; nor is it the “obvious salve to liberal conscience” that one reviewer found it. McGee comments on the reception of the play as, in many cases, missing the point; an overreaction from both those who go to relive the dirty ditties and boozy mateship of Rugby, and those brutalised by the “kick-shit-out-of-everything” approach so ardently advocated by Tupper the coach. “The Rugby audiences have belly laughed without recognising Foreskin’s mourning of the game as he once knew it. But there’ve also been those who too easily accept and cheer the knocking of Rugby, without seeing that Foreskin discredits liberal academia just the same,” says McGee. The people who’ve squirmed in their seats and sent “ban it” letters to editors have focussed on the dressing-room nudity and latched on to the language to express disgust in the filth and foul playing. “But I suspect they’ve been unable to pinpoint what disturbs them about the deeper dilemmas Foreskin faces,” says McGee.

Greg McGee’s first published work was a short story in the literary quarterly, Islands, and it too has a quintessential New Zealand setting. “Out in the Cold” is a tale set in the freezing works when “mist is lying to the second rung of the slaughter yards” and men dread the moment of stepping into the great iron doors of the freezing chambers, “round like portholes, and as they open a cloud of frozen air escapes from inside, breath from a dragon with bowels of ice.” It is a fruity story of farts and false teeth lost and found by Strawberry (McGee is a master of the colourful name) and recounted through the early morning shift while the gang loads frozen ewes from chutes off the chilling floor. The 65 dollars McGee earned for that in late 1979 paid for the typing of “Foreskin “. The next chance we’ll have to see McGee’s work will now be on television. He has written a half hour drama for a one-off series called “Free Enterprise”. It is set in Dot’s Terminal cafe but that’s all McGee is saying about it (smiling fondly at memories of Dot) Just now. He’s cagey too about his major work in progress, another play for theatre.

After all the fuss for foreskin, what is McGee most proud of? “A woman came up to me in Dunedin and said ‘I can’t help feeling sympathetic to Clean, am I supposed to?’ “Clean had bought the whole idea of social mobility, but who could blame him? “That she recognised the compassion shown to all the characters in ‘Foreskin’ that I’m most pleased about.”

–