Sep 6, 2021 People

Two hours before the biggest solo show of his career, Chris Parker is all alone. “It’s just me,” he says when I meet him in his green room at Q Theatre — a small, stark white room with a lightbulb-framed mirror, an iron and ironing board, a clothes rack, and a couple of bottles of water. There are no flowers, no friends, no family. No producer or agent or manager. “It’s so lonely. It’s soooo lonely. That’s why comedians are so sad. Because look at the job. Look at this!”

Before I arrived, he packed in the show by himself — including a large ‘felting table’ and a small digital video camera that attaches to the mic stand so the audience can see him felt on a big screen behind him. Earlier in the week he’d played five nights in Wellington, lugging his table and a broken suitcase of equipment through the rain to the venue. In a few minutes, he’ll be directing the stage show too, instructing the lighting and sound, troubleshooting technical difficulties. It really is just him.

The solo show, How I Felt, part of Auckland’s NZ International Comedy Festival, sold out and had to be extended. It is ostensibly about Parker’s obsession with felting — the technique of stabbing bits of wool (or other natural fibres) over and over again with a needle until the wool becomes firm and sculptable, when it can be turned into things like, in Parker’s case, little anthropomorphic animals playing sports. Or prominent politicians and public figures. In the show, felting works as a metaphor for our collective helplessness of the last year, a distraction from the infinite doom of online existence and, ultimately, a symbol of the arbitrariness of life. Or something like that.

According to the show, Parker picked up the hobby in March last year, near the start of lockdown, starting with the little animals that come in little sets from Daiso (the Japanese store where nearly everything is $3), but soon moving on to the actual people we watched on TV and social media every day in those days — Jacinda Ardern, Ashley Bloomfield, Siouxsie Wiles.

Once he’d amassed a collection of creations, he stitched together a felt hat, attached the little animals and people, and, later, had his portrait taken by Andi Crown looking like a surreal royal with an outsider artist crown. When he posted the portrait to Instagram, the hat (and the portrait) sparked an intense competition between Auckland Museum and Te Papa. “They were both like, ‘We want it’,” he says. “There was kind of a fight over it. And I just went with who asked first because I didn’t know how to settle it.”

Parker ended up sending the hat to Auckland Museum and the portrait to Te Papa. The hat had to be frozen by the museum to ensure it wouldn’t infect the collection. “It doesn’t feel like a huge achievement in the sense that it wasn’t a career goal — to get into a museum — but it’s so crazy,” he says, showing a full-scale replica of the portrait which he uses as a prop on stage. “It’s so like Kiwis to diminish achievements like that, and I’m like, ‘Just put yourself out there’. And the show is about that.”

A couple of weeks earlier, over filter coffee in the lounge of the Eden Terrace flat he shares with his partner, designer Micheal McCabe, and other comedy and/or creative types, he’s more enthusiastic about the whole thing. “It’s so legendary. Like, it’s the best thing,” he says, with a more healthy dose of his characteristic exuberance. The hat, the portrait and two of our country’s most prominent museums fighting for them were public proof that Parker was more than just a ‘comedian’ — that he was, in fact, an artist with a wide palette of skills, one of which (and the most popular and profitable one so far) just happened to be comedy. If he could felt a hat about lockdown and have that be a success, there’s no limit to what he could do.

“I love that it’s a thing that I have done, as an artist. I like that no one can nail me down to one thing. The artists that I have always admired — someone like Miranda July, I’ve always loved that you can’t pin her down but whatever she does, she brings her flair to it, her unique perspective to it and it’s interesting. I really want to keep being like that, keep evolving or adapting. So when I see the museum piece, I’m just like, ‘Perfect! More of that!’ I do want to consider myself as an artist, but not a serious one. Because then you can charge more, because you’re elusive. Whereas a comedian, it always has to be $15.”

Chris Parker

How I Felt’s success (it also sold out — for more than $15 — in Wellington and Dunedin) rides on Parker’s ever-increasing profile during last year’s lockdowns where, in addition to his self-documented felting journey, he posted video after video of himself playing different characters learning how to live in this new, strange world. There were the ones figuring out how to social distance on their daily walks; the ones predicting the outcome of that day’s “big announcement”; the ones buying useless shit online just to pass the time and then getting angry because it wasn’t arriving promptly; those experiencing the ecstasy of that first sip of cafe-made coffee in Level 3.

Parker’s comedy can be broadly split into two modes. His stage shows tend towards the autobiographical, telling stories from his life and leaning heavily into his sexuality for material. On stage he’s an imposing physical presence — over six feet tall, with extravagant movements that vaunt his childhood ballet training. He plays up his campness; his comic effect comes as much from his wild limbs and the tone of his voice as the words that he’s written. This sensibility informs much of his TV work, too. In a recurring segment for Jono and Ben called Chris Out of Water, he tries out typical Kiwi man things for the first time — playing rugby, backing a trailer, surfing, sinking piss with the boys — and doing his best to fit in while staying completely himself (or, at least, the fictionalised version of himself on TV). He’s a camp anthropologist, exploring New Zealand masculine stereotypes with the fresh perspective of some- one who’s never lived in that world before.

After watching How I Felt, Aaron Hawkins, Dunedin’s mayor, told Parker that he was “deconstructing masculinity while constructing craft” — a formulation which Parker likes, while stipulating that masculinity isn’t all his work is about. His comedy is more often concerned with “how we classify ourselves and how we repress ourselves”, Parker says. “Expression is a big part of who I am. Being big, being bold, being emotive, being colourful, courageous and authentic. Those things, in relation to New Zealand, are sometimes at odds with one another.”

His character-driven comedy, now more at home on Instagram than on local TV shows which tend toward chatting and pranks and quizzes, is like the result of that anthropological work into expression. Parker plays people who are both super-specific and somewhat blank, kind stereotypes filled with sharply observed detail that make people say things like, “OMG, so me!”, “LOL, seen” or “@ [friend’s name], this is us!”

“People always laugh about what is recognisable inside of themselves,” Parker explains.

His great skill (other than observation, improvisation and character acting) is being someone very specific (a tall, flamboyant gay man who tells jokes for a living) and yet able to expertly embody contemporary cliches of the white creative-class millennial. Unlike his onstage physical presence, on Parker’s Instagram videos you can never tell if he’s tall or short, big or small. He does little to change his appearance when playing different characters (glasses come on and off, there’s the odd wig, he combs his hair in a different direction), so they all essentially look like Chris Parker, but he plays them and shoots them as figures that viewers can project themselves on to.

In the same way that in the 1980s and 90s the Topp Twins were the opposite of a typical New Zealander yet were able to embody the rural Kiwiness of the time, Parker channels and disrupts white suburban New Zealand of the early 2020s. “I always go back to the Topp Twins,” he says. “They’re a miracle. They give me so much hope, that they happened when they happened. Like, there were these gay twins in New Zealand who lived in Huntly who yodelled and did characters and were activists. And New Zealanders loved them! So it’s a good reminder that actually I’m not breaking down any walls. There’s two holes that have already been pushed through the wall and they’re shaped like Lynda and Jools Topp.”

Parker’s lockdown videos came from his inherent need to be expressing himself, even when confined to his house for weeks on end. “Because it was one big shared experience, you had to go really micro into what it was that day that was really specific,” he says. “I was always blown away by the relatability of it. I thought it was amazing that people were like ‘Yes, 100% me!’ What a buzzy thing that we were all isolated yet were emotionally going through the same thing.”

The characters spring from people he’s experienced in real life, or behaviours he’s observed in those around him. Parker is good friends with Tom Sainsbury — who works in a similar idiom of Instagram character sketches, but with more pointed satire and (often) more existential darkness — and the pair often text each other with observations, especially when one of them meets someone who knows the other. “Pulling them apart,” he says. “Tom and I have always loved the mundane — tiny micro-observations of people. Everyone’s hilarious to me. Everyone’s interesting.”

Like Sainsbury, Parker also plays women, which he does with affection while taking care to avoid falling into the type of misogyny in which gay men sometimes think their homosexuality gives them licence to portray women or relate to women’s experiences in an overly intimate or familiar way. “My audience is mainly women, so I think they get it,” Parker says, pointing out that 86% of his Instagram audience is female. “The 14% male is probably gay men,” he says. “Tom’s is similar as well. Women and their mums.”

But there are some things he won’t touch, some characters he won’t play, especially when it comes to portraying cultures or ethnicities that aren’t his own. “There’s a line and it’s something I’m always conscious of. You just think, what am I doing here? Am I trying to laugh at someone who is actually struggling or am I stereotyping here? Is this sexist? Is this racist? It will always go through my filter process before I upload it and probably in five years’ time someone’s going to be like, ‘This is all fucked’, in which case RIP me, I tried. I tried to make people laugh… I hope that people don’t feel judged by it. There’s nothing worse than feeling like you’re being talked down to.

“I’m never going to put on a hoodie and pretend I’m from Onehunga and do that kind of character. But I don’t need to do that anyway — thank fuck! — because there’re so many people online who are doing that way better. Nor do I have anything to access from that. I always joke about my experience and that allows me to defend what I’m doing because I’ve gone through it. Otherwise, what would I draw on? Assumptions.”

Chris Parker has been performing as long as he can remember. “I think I was born as an entertainer,” he says. He was, in fact, born with Poland syndrome, meaning he was missing his right pectoral muscle. At four, his mother Gay enrolled him in ballet classes, ostensibly to help get him stronger and teach him some coordination, but also, Parker thinks, in recognition of his early effeminacy. “I think Mum was like, ‘Look at my gay little son, what do I do with him?’”

He remembers ballet fondly, even though he was jealous of the girls’ costumes. “All I wanted to do was wear a tutu but I wasn’t allowed to,” he recalls. “Of all the people here, give the gay boy on his own the chance! It’s going to mean the most to him. But I was always in the tights with a sash being a duke, with all these girls sitting on my knee and being like, ‘Who will he marry?’ It was so unfair — all these gorgeous dresses and the boy just had a blouse and tights.”

From ballet, Parker’s interest in performing grew. He started an after-school theatre programme, acting in at least three productions a year from the age of seven. Then there was theatre sports, Shakespeare and high school theatre. He did all of it, lapping up the attention that came with being on stage. “We would do theatre sports before assembly, before the teachers came in, and we would mock the teachers. You’d be a legend for 15 minutes, like ‘That was pretty funny’ and then a minute later they’d go, ‘You fucking gay cunt’, which kind of prepares you for comedy in New Zealand.”

He’s since gone back to his old school — Christchurch Boys’ High School, a very traditional high school in a city in which the place you went to school means a lot. Parker returned for a leaver’s dinner to find that the school was not replacing its arts centre after the 2010–11 earthquakes. So he emailed the headmaster. “There’s got to be arts in this school,” he recalls saying in his email. “Arts are vital in terms of coded safe space for the queer kids, essentially. They always end up there and if you’re not providing that space for them, they’re fucked.”

He wrote an open letter to the Old Boys’ Association advocating not just for arts but for an end to the toxic culture at the school, where he says bullying and homophobia are prevalent. He made a speech at a formal dinner, crying in front of a room of the school’s most influential people. They were stunned, but afterwards gradually came up to talk to him about it. “I knew that was the best way to get in there,” he says. “While I want to write material about it, I feel like I have to advocate for what I’m doing in that space as well… When I was at that school no one talked about being gay, which is why I think it took me so long to come out. Because there was no way you’d survive. There was no evidence in Christchurch that you could be 25, openly gay and in love.”

After high school, he moved to Wellington to attend Toi Whakaari, the national drama school with such a rigorous and competitive selection process that it was the subject of a 2005 reality TV show, Tough Act. For his audition, which required two monologues, one classic and one contemporary, Parker did Edward II, a Christopher Marlowe play which he thought would stand out because it wasn’t Shakespeare, and The Mercy Seat by Neil LaBute about a 35-year-old cheating on his wife on 9/11.

His entire life revolved around drama school, but after three years in Wellington, and despite many people’s assumptions about his sexuality, he still hadn’t come out. “I was a mess, I didn’t know who I was,” he recalls. “I was just not in my authenticity, but then trying to express myself in these other ways. It’s very queer to me — you can see who you want to be but you’re scared of that so you’re trying to be everyone else… All the drama school teachers would try to make me come out but I would always withhold. I had a full mental breakdown one day. Classic stuff: ‘I don’t know who I am!’ I looked in the mirror and didn’t recognise myself. I was obsessed with being an actor, so I put all my energy into that. I was trying to avoid my sexuality.”

At the end of drama school, attendees perform monologues for ‘Industry Day’ — “a couple of casting directors, some people from Circa and some talent agents,” he explains. Parker did a monologue from The Eros Trilogy by Nicky Silver “about a guy having his first sexual experience and it going terribly and jerking off in the toilets afterwards”.

“I remember nailing it,” he says with no sense of false modesty — Parker, an extra extravert, often speaks of ‘nailing it’ or ‘killing it’, defying our country’s penchant for stern self-deprecation. “I think I was good, but it was hard because I wasn’t out. And I’m very aware that I access camp qualities and hit on my sexuality a lot in comedy so I wonder what I was pulling from. But I knew I could get laughs and I knew that was very satisfying for me. It gave me a sense of self-worth. Because you might not necessarily like yourself, but I knew that others thought I was good and funny. And I was like, ‘Great, I can hate myself but be really good at comedy and like that others like that I’m good at comedy’. I’ve since been to therapy about this so I’m getting really good at unpacking this: Being good at being on stage allowed me to feel good about myself at a time I didn’t necessarily feel good about myself.”

The Industry Day was a success. Parker was cast in Toys, the BATS Theatre Christmas fundraiser, which gave him the opportunity to do a comedy monologue in front of “all the cool kids of Wellington theatre”. “I remember nailing that one as well,” he says. “I knew from that point on that I could do comedy theatre stuff and not be that serious actor.”

Parker relocated to Auckland in 2013, encouraged by his friend Leon Wadham, who had landed a role in the final season of Go Girls. He moved up with Eddy Dever, whom Parker had been improvising with since their teens in Christchurch, and the two arrived just in time to be part of the founding team of Snort, an improv comedy troupe which fostered almost an entire generation of New Zealand comedy: Rose Matafeo, Tom Sainsbury, Alice Snedden, Guy Montgomery, Laura Daniel, Joseph Moore, Rose Eli Matthewson, Donna Brookbanks, James Roque, Nic Sampson, Alice Canton, and so on. A year later, Nic Sampson got a job writing for Jono and Ben, and the following year Parker did too. “I just kind of slipped in,” he says. “Then Hudson & Halls happened.”

In 2015, Parker was cast in Hudson & Halls Live!, a stage show about the New Zealand TV cooks Peter Hudson and David Halls. Hudson and Halls were a gay couple who, despite not being professional chefs (though their dinner parties were legendary), became huge stars in 1976 when they graduated from a ten-minute slot on an afternoon show to their own hour-long cooking show, Hudson & Halls. Parker starred as Halls and Todd Emerson as Hudson. The show was a huge hit, produced by the Silo Theatre but playing around the country over the next two years, bringing Parker to a national audience. The artistic director at Silo gave Parker him a key piece of advice. “To be on stage is a privilege and you’ve got to respect the opportunity being granted to you to have that time in front of that crowd,” he remembers. “I hate when people waste an opportunity. I will never give up on a show. Ever. I will never give up on an audience. I did 250 shows of Hudson & Halls. And killed every one! Because it was so important to me. I was never like ‘Let’s just get through this’. That’s the same for my other work as well.”

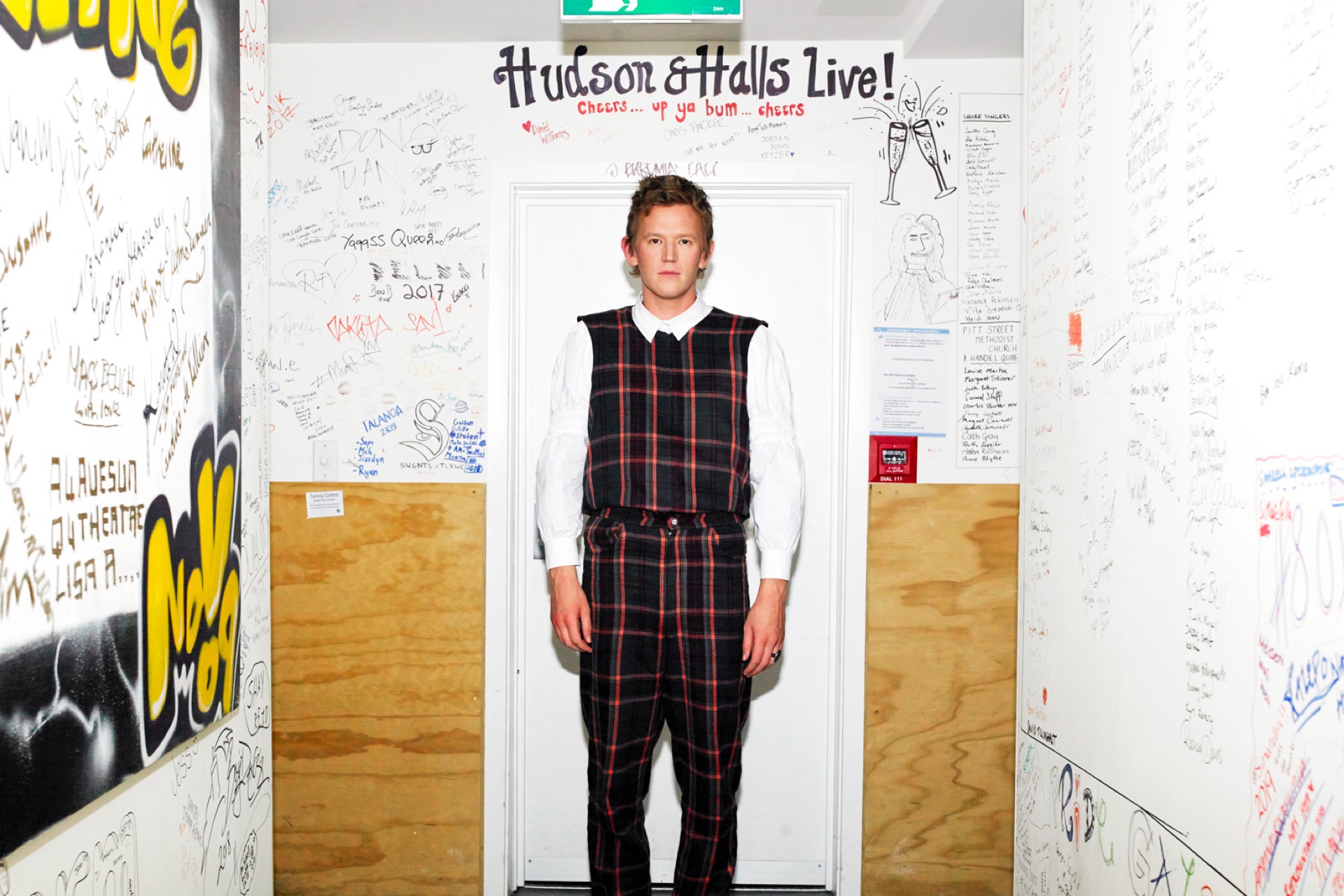

Parker in the green room at Q Theatre

Backstage after the show, I meet Parker again briefly. He’s still alone. Some friends are hanging out in the Q Theatre bar waiting for him, but he’s still got to pack the show down, fold up his table and lug it to his car.

“That was a fun show, eh?” he says, more like someone who’d just seen a show rather than performed it. “Loved it! Thrilling shit!”

“Feel good?” I ask him.

“Oh my god, I just love being at that scale,” he says, still riding the performance high. “Like, get that table out and get me out there. Next year, I’ll be going haaaard.”

Parker wants to play The Civic, though he’s scared of losing control of the detail when working at that scale. But he wants to do more than just The Civic, more than just comedy. He wants to continue to grow and change and adapt. He’s working on a feature film script inspired by growing up in Christchurch, going to high school there and returning as an adult; about the safe space the arts can provide for kids who don’t fit in. He wrote the first draft during lockdown, in between felting sessions and making videos. Working title: Drama Fags.

“I really want to make movies,” he’d told me earlier, that morning in his lounge. “It’s the next step, the next challenge, the next outlet. The next form. I’m in a museum. I’ve done TV, theatre, comedy. I haven’t done a book. I haven’t done a perfume line.”

We say goodbye as he walks back toward the theatre, to go back on stage to pack up his table and load it into his car, alone.

—

This story was published in Metro 431 – Available here in print and pdf.