May 26, 2016 Music

The Colour in Anything

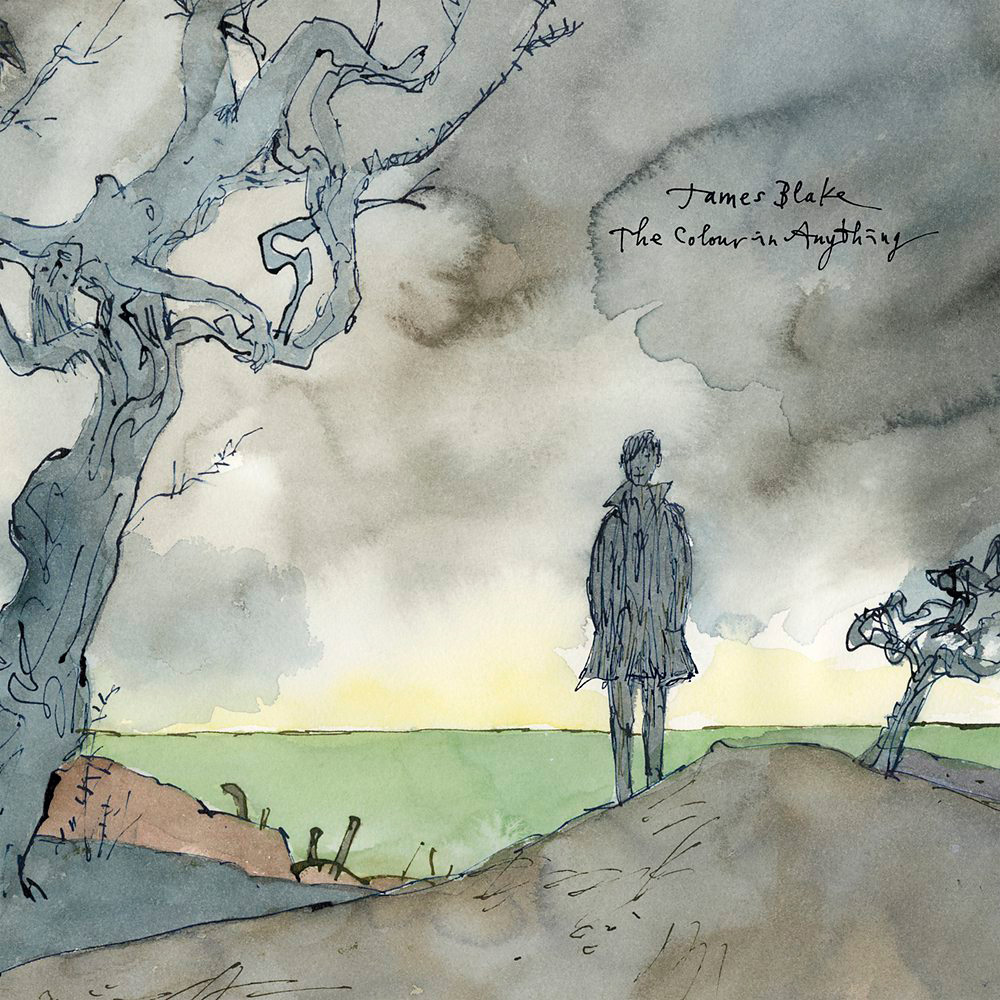

The Colour in Anything

James Blake

(Universal)

While far from a household name, James Blake has had enormous influence over a new generation of song stylists. His often emotionally desolate balladeering isn’t exactly chart friendly, and yet stars as big as Beyoncé have taken him to their bosom.

The question is: in the three years since his second album, Overgrown, caused ructions in the space-time musical continuum, has his art suffered through exposure to the withering effect of celebrity endorsement?

It seems not. The magnum opus that is The Colour in Anything fails to come up with the suggested Kanye collaboration (excellent news) or any rap-guest turns (even better) and there are no helium-voiced divas (phew!), just the cracked, simultaneously emotionally piercing yet fragile sound of Blake’s own modified voice and piano, and a judicious use of electronic armoury.

The idea of the singer-songwriter is so tied to tradition, so ossified by our expectation of some guy and a guitar, or some guy sitting on a piano stool, that when James Blake came out with his first set of 12-inch EPs in 2009, it turned tables. His self-titled album in 2011 made it clear that this wasn’t just some electronic music producer dabbling at song, but a young guy with a new approach to the construction of the ballad.

His home-baked reconstruction of song via the influence of dubstep, the bass-heavy dance genre, made him profoundly different from the rest. Taking just the electronic elements he wanted —the sense of vast space, the occasional drop into window-rattling sonics — Blake’s music was at once high-tech and bedroom-created, resulting in the kind of glossy but intensely personal sound to match his edge-of-psychosis balladry.

His home-baked reconstruction of song via the influence of dubstep, the bass-heavy dance genre, made him profoundly different from the rest. Taking just the electronic elements he wanted —the sense of vast space, the occasional drop into window-rattling sonics — Blake’s music was at once high-tech and bedroom-created, resulting in the kind of glossy but intensely personal sound to match his edge-of-psychosis balladry.

While the musical backdrop he constructed was capable of an impersonal, steely, machine-tooled groove, his voice was intimate, letting you right into his head.

While the musical backdrop he constructed was capable of an impersonal, steely, machine-tooled groove, or a vaporous void to illustrate the emotional torment, his voice was intimate, letting you right into his head. Voice-modification has become the standard in popular music, but the software is mostly used either to make a bad voice sound good, or for novelty value. Blake used his Vocoder to, ironically, enhance the intimacy and sense of fragility.

Music as a direct articulation, shaving off the dull performance convention of picturing some guy singing and playing an instrument: that’s what James Blake brought to modern song. But now on his third long player (and The Colour in Anything is a very long listen), what is there to add? And with hundreds — if not thousands — of young songwriters now aping his style, could the rhapsody start to bore us with repetition? The answer: not yet.

In a sense, The Colour in Anything is more conventional than those first two albums, but he created the convention. It’s too long, and a few of the simpler voice and piano ballads aren’t quite as riveting as Blake imagines them to be. But taken in 20-minute portions, it’s a killer, and he refuses to prettify his palette, frequently using discord and ugliness when it aids and abets the exploration of his interior world. For all that, it’s a thing of beauty, and deserves to make it into the inevitable “best of 2016” lists at year-end.