Mar 5, 2014 Music

It starts incredibly. “Rattlesnake” powers up like a neutron bomb, and twitches along like a virtual Talking Heads for three minutes and thirty four seconds with an outrageous kinetic energy while Annie Clark sings about being out in the desert, naked, sweating, feeling like the only person left in the world. What a picture.

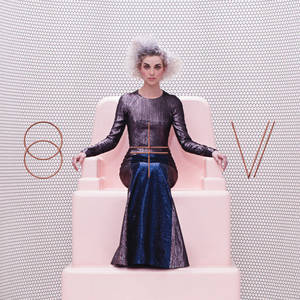

It would be churlish, unreasonable, to expect the rest to maintain the momentum, and it doesn’t. But Clark’s fourth solo album as St. Vincent is an incredible exposition of unfettered creativity, a powerhouse of focused madness that parallels Prince and Kate Bush at their respective peaks; except that hers is an explicitly, inherently digital universe.

Having collaborated with Talking Heads’ David Byrne on the rather special Love This Giant (2012), it’s not surprising to find remnants of that seminal band’s circuitous, slightly psychotic grooves snaking through some of the songs on St Vincent. But to her credit, Clark’s personality is so strong that after it’s all over, you’re overcome with the sense that St. Vincent is its own genre: it just doesn’t quite fit anywhere.

Trawl through YouTube and Clark’s singer-songwriter roots are revealed, especially in early live performances, but the songs here aren’t just winsome lines and pat melodies with overdubbed accoutrements. Her lyrics are smarter than they are deep, but that’s okay. She enjoys word play, and it’s much more fun to hear lines about snorting pieces of the Berlin wall (“Prince Johnny”) and taking out the garbage and masturbating (“Birth In Reverse”) than the usual humdrum lovesick stuff.

But back to St. Vincent’s supra-digital world: what makes St Vincent so alien on first encounter is that it features Clark performing on guitar, and various musicians contributing drums, synthesisers, piano, harpsichord and horns, and yet with the exception of her vocals, it all sounds as though the performances have been fed into a computer, then spat out in mutant form. She’s an admired guitarist, but there’s nothing here resembling the tones or textures of a conventional guitar, acoustic or electric: everything is heavily processed. The result is a kind of radical alt-rock vs. prog rock, the synthesisers buzzing and swooping like 1970s Rick Wakeman, while Clark’s Broadway vocal inflections add yet another layer of weirdness. The first time I heard it, I hated it. I’m glad I went back for seconds.

It may not be the sound of now, exactly, but St Vincent is the sound of St. Vincent’s now, and it’s with respect that I say she’s not like anybody else, out on her own, making itchy, scratchy, provocative, and jerkily funky head music for the body. Or is that body music for the head? Make that a combo.