Nov 1, 2016 Music

I have decent recall of a week ago but my distant past remains out of focus, fuzzy. Sometimes the screen is blank but, oddly, the soundtrack comes through clearly. I know exactly when I first heard Auckland’s all-girl band Fair Sect Plus One (the “one” being the male drummer) coming out of my Sanyo transistor. Their version of “I Love How You Love Me” was arresting. It was probably the bagpipes. Not a lot of pop songs in the 60s — or indeed any era before or since — deployed bagpipes.

I remember the Keil Isles, the Chicks opening for Australian pop star Normie Rowe at the Crystal Palace, Ray Columbus and the Invaders on tour with the Stones, Mr Lee Grant on television. My first New Zealand music experience was my older sister’s Johnny Devlin EP Hit Tunes from the late 50s. The song that grabbed me was “Matador Baby”, one he’d written about the fashion of high-waisted matador pants for women.

Even today, the record’s cover — Johnny holding a Coke bottle, the sponsor’s product — brings back memories: the family radiogram, the print of the raging sea above the fireplace.

I suspect many people are like me: A few bars of a song almost forgotten or a battered record in a second-hand store can be a Proustian prompt to memory. Music is like that, it sneaks into the subconscious or — because a song was something we fell in, or out, of love to — we impose personal meaning on it. Songs are the soundtrack of our autobiographies and musicians often articulate intimate, social, political or cultural concerns in a way others can’t.

Which is why the exhibition Volume: Making Music in Aotearoa at Auckland Museum will occasion many “Oh, I had one of those” moments — especially in the reconstruction of an 80s record store with almost 200 album covers complete with band credits and recording details.

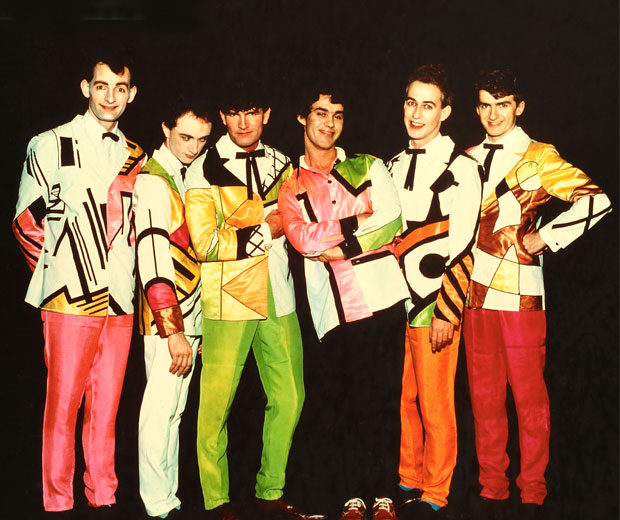

But there are objects about which no one could make that claim. Gold discs, artists’ private notebooks and hand-written lyrics, stage costumes (including some of Noel Crombie’s handmade Split Enz outfits), musicians’ memorabilia, rare instruments and artworks (among them Chris Knox’s massive dot-painting cover for his 1991 album, Croaker), archival video clips. Lorde has been very generous and, yes, there are 10 guitars. But not just any 10.

Through more than 200 objects from more than 60 lenders and more than 450 images and photos, Volume embraces New Zealand popular music from Johnny Cooper’s enjoyably inept version of “Rock Around the Clock” in 1955 (this country’s first rock’n’roll recording) to beautifully shot films of newer artists such as Louis Baker, Georgia Campbell and Raiza Biza performing in museum locations.

Through more than 200 objects from more than 60 lenders and more than 450 images and photos, Volume embraces New Zealand popular music from Johnny Cooper’s enjoyably inept version of “Rock Around the Clock” in 1955 (this country’s first rock’n’roll recording) to beautifully shot films of newer artists such as Louis Baker, Georgia Campbell and Raiza Biza performing in museum locations.

The exhibition presents what might be the shock of the new alongside the frisson of the familiar. And because Volume — a neatly ambiguous title — covers such a long timeline, in reverse chronology from the present back to our rock’n’roll rebels of the 50s, it has been years in the making.

For Mark Roach of Recorded Music NZ — an umbrella organisation which, among other things, collates the weekly sales charts, organises the annual music awards and launched the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame award in 2007 — the path to Volume began in November 2012 when he started researching and conceptualising the idea for a physical Hall of Fame, because no actual “hall” currently exists.

A year later, Roach — who heads marketing and special projects for Recorded Music NZ and is a spokesman for the NZ Music Hall of Fame Trust — pitched the idea of an exhibition of New Zealand popular music to the museum.

Musicians often articulate intimate, social, political or cultural concerns in a way others can’t.

“In that interim period, it became apparent that to do a music museum you needed to start smaller and test the waters, so an exhibition was an obvious choice,” he says. “Basically I just cold-called the museum in September 2013, met with them in November and they agreed to it in principle almost straight away.”

Museum exhibition developer Esther Tobin says she knew “it was going to be huge and the scope would be incredibly wide. It was suitably overwhelming, but I knew how big the story needed to be.”

It was also a journey of discovery for her and others involved: “There were pockets of things that, through your age and when you grew up, I felt comfortable with. . . like the hip-hop story, which felt very familiar. But then there were other areas which were completely new.”

Tobin is now a massive Sharon O’Neill fan after discovering her music through the project.

I came on board in early 2015 as the exhibition’s content adviser. What that content might be was thrashed out by a dozen or so people intimately connected with New Zealand music. It was important Volume not just be objects in cases but have components which offered hands-on engagement and allowed visitors to get some sense of what it was like to be “there”. Wherever that “there” was.

So yes, there are display cases of memorabilia, video montages encapsulating decades, compiled by Paul Casserly and his team, and plenty of memory-jolting eye candy. But visitors can also get behind the mixing desk of a mocked-up recording studio, play the DJ, learn an iconic Kiwi song in a 1970s pub venue, or dance on a replica set of the 60s television show C’mon.

And with so few actual record shops around these days, browsing in the store may elicit that Proustian response: “Oh, I had one of those.” In the countdown to opening night, Tobin says if she had to choose one area to take guests to get the feel of the show it would be the pub.

“Obviously there are the four major interactive elements but for me the most important is in the 1970s and the live band set-up. Because visitors have a chance to get their hands on a bass guitar, electric guitar, drums or synth — sometimes for the first time.

“It’s not an easy choice for the museum to set up a live-band situation but it’s where people can have a go.”

And her selfie spot? “The C’mon studio, because it has a projection of actual dancers in full colour, bright orange, bobbing away. That’s a striking part of the show.”

Volume also has an agenda beyond the pleasure principle. It is designed to acknowledge and honour the breadth and depth of New Zealand music, especially inductees into the New Zealand Hall of Fame and those whose songs and stories have spoken to and from us in Aotearoa New Zealand.

That is a huge constituency over 60 years and although we adopted a policy of inclusion — the second of my guiding documents was a whopping 30,000 words detailing artists, the social and political context of the decades, timelines and themes — Volume is also constrained by the exhibition space, albeit cleverly designed by Lesley Fowler with visual allusions to records, CDs and speakers.

That is a huge constituency over 60 years and although we adopted a policy of inclusion — the second of my guiding documents was a whopping 30,000 words detailing artists, the social and political context of the decades, timelines and themes — Volume is also constrained by the exhibition space, albeit cleverly designed by Lesley Fowler with visual allusions to records, CDs and speakers.

The potential volume of Volume meant considerable distilling and culling. Much as I might have liked, perversely, to include Southland’s Pretty Wicked Head and the Desperate Men, that was never going to happen.

“The willingness of people in the industry to share their objects and images with such grace and wholeheartedness was amazing,” says Tobin.

Some musicians were surprised and flattered to be included, she says. For others, it acknowledged they are still out there working. Some saw it as exposure, and for a few there was “a deep-seated frustration with how they hadn’t been accepted over the years — this was a chance to get it right”.

Much as I might have liked, perversely, to include Southland’s Pretty Wicked Head, that was never going to happen.

The long game, after Volume closes, is a permanent exhibition space worthy of these creative artists, just as we have galleries for our visual and plastic arts. Volume isn’t an end, but rather a possible beginning.

Roach — who, like me, has been through many international museums of music — says he’s already thinking “how to maximise the momentum Volume will bring, so there isn’t a lag between this finishing, but the impetus and goodwill generated will allow us to move ahead”.

Roach envisions an inclusive museum charting the history of popular music, including space for a dedicated Hall of Fame, with something akin to Volume as its bedrock.

“It could be a whole new institution where you could run an exhibition about purely Maori showbands, for instance, and have space dedicated to a specific story in more depth than we currently have in this exhibition.”

Such an institution could also bring in touring exhibitions like the recent David Bowie Is, which made it to Melbourne but not here. “No one has said, ‘That’s a really dozy idea,’ and when I talk big-picture stuff, I envision it with a recording studio, rehearsal space, a business incubator, a performance space… a general HQ of New Zealand music.”

That’s a lofty but not unrealistic vision, and one worthy of the hundreds of artists whose work has helped define us as a people, given us pleasure and memories, and created a nation with a unique musical identity and history.

Like a song released into the world, Volume is the culmination of ideas and effort… but the audience will make of it what it will.

Volume: Making Music in Aotearoa, Auckland Museum, October 28 to May 21.

This article is from the November 2016 issue of Metro