Aug 22, 2019 Music

After staring death in the face, Nathan Haines is ready to embrace his past and map a fresh future.

When I turn up at his Greenlane bungalow, Nathan Haines is making the most of the early winter sun by hanging out the washing.

We adjourn to the dappled light of the living room, where he reveals himself to be a turbulent conversationalist. His thoughts turn into sentences that dart around like a saxophone interrogating the nooks and eddies of a solo, but can also riff along on an extended narrative, or surprise with pre-determined structure. He’s always in control, and today, has got a lot to say, even if he hasn’t quite got the voice to say it with.

We choose to meet in the quiet of his home, because the nine-hour operation to remove a large tumour from his throat in December 2017 has reduced the sound of his vocal chords to a soft, mentholated blur. Haines now understands why his hero, jazz titan Miles Davis, never spoke to his audience: a throat operation had left him with a voice that sounded like a sewer trap.

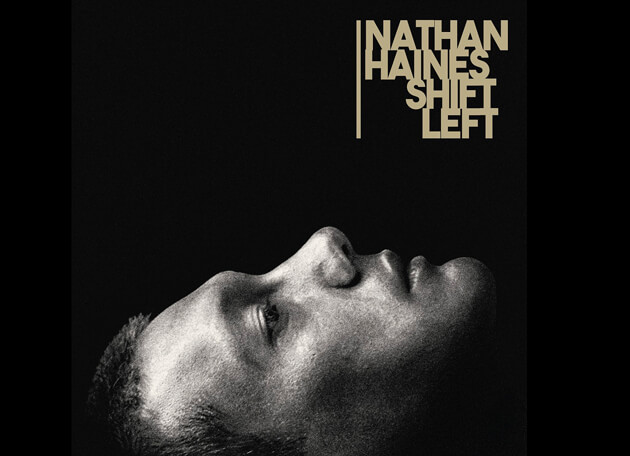

Our own jazz-fusion legend is optimistic that a further operation will reanimate his voice. The vocal apparatus isn’t damaged, he explains, it’s just scarring from the operation that’s inhibiting its full functioning. The voice: it’s just one of the indicators of the seismic shift in Nathan Haines’ life since that shock cancer diagnosis, but it’s better than death. And circuitously, it led right back to the incredible, unrepeatable beginning of his storied career: the iconic 1995 debut album, Shift Left.

After a year of intense radiotherapy and multiple follow-up operations, Haines was recently given the all-clear. It’s been an 18-month trip that’s irrevocably changed his life, and opened up emotional scars that need their own healing, but it also provided a kind of pause that finally gave him permission to revisit that important first step, an album that the former child prodigy released when he was just 22.

Whether we know it or not, we’ve all heard Shift Left, because it’s beamed out of hundreds of cafes, bars and hair salons over the past 25 years. It was a game-changing fusion of acid jazz and hip-hop with a small but potent infusion of Pacific influences that made it an instant classic. And on August 24, Haines takes to Auckland’s Town Hall with the original line-up — including Manuel Bundy on the decks and Haines’ all-time favourite drummer, Mickey Ututaonga — to perform Shift Left in its entirety, in a follow-up to its recent, lavish vinyl reissue.

Having mastered the flute at six, by 14 Haines was playing traditional jazz in his father’s band on his favoured instrument, the saxophone. Winning the AGC Young Achievers Award at the age of 19, he headed off to New York to study the art form, but his epiphany was experiencing the “conscious” hip-hop of groups like A Tribe Called Quest and the Jungle Brothers. It changed the course of his own music. “I had the great advantage of getting to New York and living and surviving as a musician in downtown Manhattan,” says Haines. “That was when hip-hop was still underground but massive, and it was a very special time. I brought that music back to New Zealand and mixed it with what I was playing. But of course, I didn’t want to make a record with samples, I wanted to do it live.”

Surprisingly, the songs weren’t composed on saxophone, and there was very little improvisation. “I had a little sequential circuit six-track keyboard, and I wrote a lot of the tunes on that. I’m not a keyboard player, but I would just write stuff down and sequence it. I had a very clear idea of what I wanted.”

The album sessions were laborious and when it was done, there was an intense period of post-production where the whole thing was reprocessed by a Fairlight emulator. “I wanted to get the fuck back to New York, where I was living at the time, and I remember my father waiting in the car with my bag and I was in the studio and so over it by then. I put so much time and energy into the record, and then spent four more months on post-production. When I got the CD, I was like ‘What the fuck? It’s got Pauly [Fuemana of OMC] rapping on it.’” He hadn’t been told about the spoken-word additions.

While Shift Left created seismic waves in New Zealand, by 1997 Nathan Haines had moved on. He was living in London and making 12-inch singles for the legendary Metalheadz drum-and-bass label when he got a call from Fuemana. A song Fuemana recorded with Alan Jansen, “How Bizarre”, had gone ballistic and he needed backing musicians.

During a couple of years in which he put his own career on hold, Nathan suffered the insane indignity of having to mime trumpet on a European promo tour, where Pauly-mania was so intense that he got mobbed. The American tour was like an unfunny Spinal Tap. “I spent a year of my life touring there, and it was really disturbing seeing the machinations of the record industry first hand. We just felt like we were being pushed onto this boat, onto this sea of sharks. It was really awful and I don’t think I ever really recovered from the experience.” And neither did Fuemana: “I saw him go from having money to having nothing. The last time I saw him, he was sitting outside the Milford Police Station barefoot. He was a mess. And the next thing I know, he’s dead.”

Haines had his own demons. Over the next decade, he remained in London, where he became a respected figure in the vanguard of acid jazz/nu-jazz/call-it-what-you-will, and got to work with the respected jazz singer Marlena Shaw, who he considers a mentor. Back at home, albums were met with enthusiastic approval and awards. But the high life had its downside. By the late 1990s, he was hooked on heroin, and when he shook off that habit, alcohol became his crutch. Raised to adore everything about jazz culture — including the lifestyle — and enmeshed in the club scene, the temptations were too numerous, even as they masked a deep malaise.

“Jazz musicians invented drug taking as a culture, and so many things which we take for granted today,” says Haines. “They were the original outsiders. They were the original punk musicians, except that they could play their instruments. That’s how I saw myself when I was young, that’s why I went down that path I did, because I wanted to shake up people’s perceptions. Unfortunately, the romance of the journey, the drinking and the drugs, has led to a lot of mental anguish and anxiety for a lot of musicians. Look at Chris Cornell, who’d been straight, who’d been in recovery for a long time, but it still got him in the end. I’m very aware of that myself.”

By the time Haines returned to New Zealand in 2013, his international accomplishments were undeniable. He’d performed at legendary jazz club Ronnie Scott’s, had an agent and a bunch of albums he was proud of, together with a press pack full of glowing reviews. “I was also drinking heavily, and had incredible anxiety. I’d wake up after a huge night and I’d walk out into the kitchen and I’d think my life was at an end. So what did I do? I drank more.”

Knocking off the booze helped, but it raised a raft of other issues. Having had a son, Zoot, with wife Jaimie Webster Haines in 2014, the full force of adult responsibilities hit home. Economic survival gnawed away at his self-belief. He was abandoned by his record company, which was going digital-only. Getting the funding together to make an album or launch a tour was a major impediment. “I came back to New Zealand, I couldn’t get a record out. Very frustrating. Then I get cancer. It was the perfect storm. Looking back, it was like a mid-life crisis life-changer, and it was probably inevitable.

“At a spiritual level, something needed to happen in my life, so I’m turning this around to positivity and creativity and taking this as the start of my life, not the end. I’m grieving for my old life, but I’m also taking it as a new start. I don’t have a choice. If I go back into my old life I will die, and I want to be here for my son’s 21st, and to be present as a human being. That’s now more important to me than my career.”

This piece originally appeared in the July-August 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline ‘There and Back’

Nathan Haines plays at the Civic on Saturday, August 24. Tickets and more information here.