Oct 31, 2019 Music

New Zealand didn’t have a record-pressing plant for more than 30 years, until a criminal lawyer and a property developer quit their jobs and opened Holiday Records.

As visionary business ideas go, it’s hardly in the same league as Facebook or the iPhone, but the need for one is so obvious that you can’t help wondering: why the hell didn’t anyone think of it before?

There hasn’t been a record-pressing plant in New Zealand since the dawning of the era of the compact disc in the late 1980s, when EMI — rumour has it — dumped their machine in the sea to rust away like an old shipwreck.

And despite the incredible revival of the vinyl record industry, until now enterprising musicians and record labels have had to send off their audio files to Australia, or further, if they wanted to have their musical vibrations etched in grooves on black plastic.

Ironically, it took two complete novices to open New Zealand’s first record- pressing plant in over 30 years. Joel Woods and Ben Wallace — both 28 and pals from university days — had careers mapped out in criminal law and property development respectively, and both were a bit fed up with their jobs when the idea came to them. As a musician, Wallace had become aware of the complete absence of local pressing facilities.

It turns out that there’s no shell-encrusted pressing machine in Wellington Harbour after all; it was actually shipped overseas. But the fact remains that despite the rapidly growing demand for vinyl first precipitated by the 12-inch DJ phenomenon of the late 90s, and the long wait times and prohibitive shipping costs for anyone ordering from overseas, nobody seems to have seriously considered the possibility of a local pressing plant. Until now.

“Ben wanted to get some vinyl pressed for his band, and that’s how the opportunity arose,” says Woods. “He realised he couldn’t do it here, and that’s when the research started, and he got me on board. We realised there was a huge gap in New Zealand, with only one pressing plant in Australia and huge waiting times.”

Holiday Records is a thousand light years from traditional images of old-time record-pressing plants full of crusty men in lab coats bending over vinyl masters, and middle-aged women wearing horn-rimmed spectacles sliding records into sleeves. Their base in Wellesley St West is a minimalist-designed record store from which customers can view the machinery at work through a large window. If you’re lucky, you might even catch the “chefs” at work.

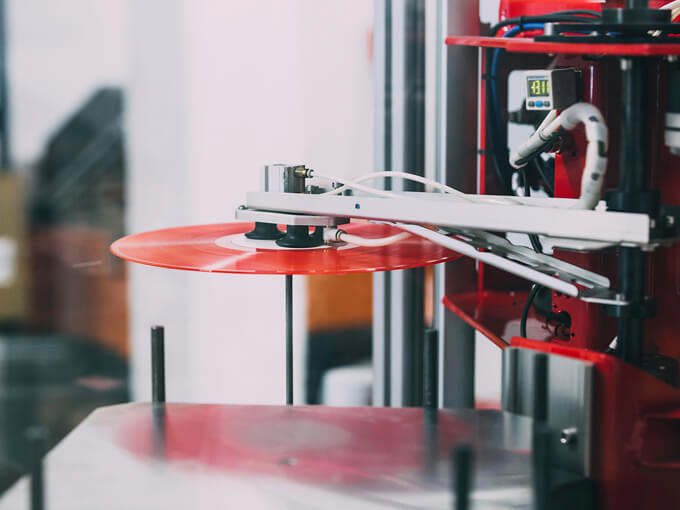

Woods and Wallace briefly considered tracking down and piecing together an antique pressing plant, but they quickly came across an obvious solution: Canada’s Viryl Technologies have created a very 21st-century take on the record-pressing plant that reduces it to one relatively compact, automated machine. It’s a marvel of technology that’s analogue in all the ways that matter but utilises digital read-outs and monitoring.

“It’s fully automated and they do lots of training and give you assistance throughout the year as well, so it’s the perfect fit, really,” says Woods. “There’s an informal community of people that are pressing with them, so we help each other out as well.”

It all got under way two years ago when Woods and Wallace took several research trips to North America, where they ended up buying the pressing plant and undergoing training. “We did a tour around the States having a look at pressing plants, and then about a month’s training with them on-site in Canada, because obviously we’re new to the whole pressing side of things,” says Woods. “But the machine’s pretty good and it’s well designed and you can learn how to press a record pretty easily. It took a bit of time but I think I’ve mastered it now!”

The obvious benefit for local bands and musicians is that rather than grinding away in some industrial suburb, Holiday Records is right there in Auckland’s CBD and designed to be highly accessible. While Woods and Wallace still have to contend with the cost of shipping the raw materials to New Zealand, the combination of cost-savings, convenience and care — along with the ability to oversee the process — makes getting it done locally quite compelling.

But what of the environmental cost of a so-called vinyl record? PVC is actually a type of plastic, so in some ways the “vinyl sounds better” movement seems counterintuitive.

Woods acknowledges the format’s inherent problem. “This machine is by far the most environmentally friendly pressing machine, but that doesn’t take away from the fact that we are pressing on PVC plastic, and plastic isn’t the best for the environment, and there is no alternative to that at the moment. PVC is simply the best-sounding.”

On the other hand: “There are offcuts and wasted records but we do have a grinder in the corner so we grind it back down, so there isn’t really any wastage. And obviously, records are made to last a while, so it isn’t like they’re going to the dump.”

He’s got a point. Vinyl records can last a lifetime if stored well and treated carefully, and even the mountains of Rolf Harris and Nana Mouskouri records sitting unloved in opshops and cheapie bins seem to defy the dumpster.

As for quality, Holiday Records currently source their PVC from Italy, which has a reputation for click and “pop”-free vinyl, and the processes required by the machinery should lead to better quality control than the steam-punk machinery of the past.

“This machine makes it easier to control, because you have to dial every job in with temperatures and times and pressures,” says Woods, “so by the time you press ‘go’, you expect it to be pressing some good records. We do have a big emphasis on quality, especially because we’re brand new and if we get a reputation for doing anything poorly, I don’t think anyone’s going to be bothered working with us.”

The Viryl Technologies machine can turn out a vinyl record every 35 seconds — about 800 each working day — which means that substantial print-runs are easily achievable, but typically, independent local bands are cash-strapped and looking at small numbers. Woods warns against going for the minimum 150 units, however.

“Anything less than that becomes inefficient for them and us, and it’s only going to be another 50 to 100 dollars to do 50 more, so it’s like, ‘why not?’ It makes sense to do a lot more, because there are set-up costs involved for any job whether you press 100 or 1000, and vinyl is a good income source for any artist as well.”

He’s right. With minimal returns for most bands from the digital arena, going on tour with a box of vinyl to sell at gigs can make the difference, and when they’re down to their last units of a pressing, they can always flog it off on Discogs, especially if it’s a beautiful-looking thing.

And yes, a range of coloured vinyl is available.

This piece originally appeared in the September-October 2019 issue of Metro magazine, with the headline “Round like a record, baby”.