Jun 22, 2021 Music

Twenty years after its release, Che Fu’s album Navigator remains at the high water mark of Aotearoa Futurism.

It’s 2001 and a guy who looks a bit like me and shares the same interest in Star Wars and kung fu has the full attention of a crowd in Auckland Town Hall. His name is Che Ness, a.k.a. Che Fu, and he grew up a few streets over in Ponsonby. It’s 2015 and the unlikely fusion of Star Wars and rap music has brought me to Radio New Zealand to work on a documentary about Aotearoa Futurism with my haumi Sophie Wilson. The first person we want to talk to is Ponsonby Che, the Māori-Niuean science fiction pioneer. It’s 2021, and Che Fu is returning to perform in Auckland Town Hall with his now-adult son, holding the crowd’s attention once again.

Every great tale has a return arc, everyone who Iliads their way out should Odyssey their way back, so when Che Fu & The Kratez play at the Auckland Arts Festival (on from 4-21 March), they bring a suitably large story to a close. The occasion marks the 20th anniversary of Navigator, a landmark album that was certified triple-platinum, won five national music awards and had a cultural impact that rings out into the present day. A story as large as Navigator’s will have many retellings and interpretations, but we focus our own on the impact it had in cementing a movement we call Aotearoa Futurism, the undercurrent of Māori and Pacific culture that addresses, deconstructs and plays with notions of space and time.

Back to 2001: Che Fu is already a leading figure in the Aotearoa hip-hop scene and committed to a renaissance of long-time veterans and emerging talents. Graffiti, breakdancing, DJ culture and rap had rebirthed themselves in full aesthetic scope as the millennium raced towards its end, but the culture still sat at the margins of mainstream acceptance. When Navigator is released, however, it shoots straight to number one on the charts and stays there, breaking an invisible barrier that fans and fellow artists will pass through at speed.

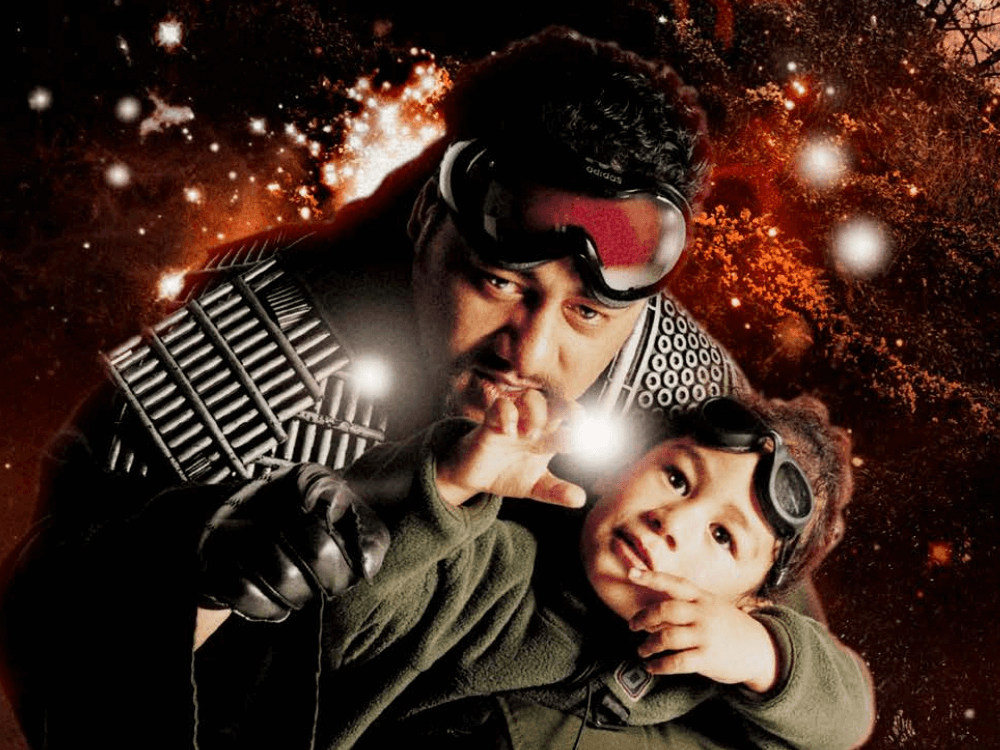

The cover art for Navigator might be the nerdiest artefact of our collective cultural past. Che is pictured in a full rebel alliance outfit holding a holographic projector in his hand and carrying his young son Loxmyn on his back, a homage to Daigoro and Ogami Ittō from the seminal Lone Wolf and Cub manga. In subsequent interviews, Che revealed that the night-time forest setting is based on images of Chewbacca’s home planet (Kashyyyk, for the curious). These details are thrilling for the comic-geek set, but for the tens of thousands of people who bought Navigator, the image reads simply and sincerely — family, technology, nature — all of which are woven into the composition and lyrics of the album.

“Misty Frequencies” is a soul-styled narrative that leads the album and tells the story of a young boy, hunched over a radio receiver, discovering music that moves him. A second verse relates the story of a young woman, head-strong and steady, setting out into the world. Without ever stating the fact, it’s clear this is a biography of Che and his partner, set years before their meeting but already connected by a shared purpose. The familial theme is doubled on the soulful “Catch One”, describing the coupling of Che’s own parents during the 1970s activism movements. Whakapapa is declared, secured and celebrated.

“Share the Info” is a boom-bap critique of the information landscape in 2001, when the Labour government had recently obscured facts about genetic-modification trials and a burgeoning internet had already begun destabilising factual consensus. In continuation and contrast, “The Abyss” has Che in full control of the modern as he bounces battle raps over one of the few allsampled, all-programmed productions on the album. The lyrics leak details of Technics, 3D rendering, document downloads and dissemination while P-Money winds a showcase turntablist break. Technology is a reformist tool, a vector of control for those with control over it.

Che shares a spotlight with long-time bros Phatmospheric, Hazaduz and Ras Daan on “The Mish (2)” a sequel song about the raruraru (difficulty) involved in securing a sesh. Apart from travelling across the whole city for a fifty, the tribe of MCs have to put up with over-policing and harassment. “Supplied by the earth, denied by the law, I can think of more criminals they should be looking for.” Navigator draws a link between nature and its subjugation by law, a colonial control written onto the earth itself.

Whakapapa, technology and nature are heady enough topics as it is, but Navigator covers even more latitude on its journey across te reo (“Kotahi”), Rastafari (“Roots Man”), government (“Top Floor”) and straight flexing (“The Natural”). On a hiphop album where only half the tracks contain rap or turntable scratching, Navigator also draws a path across a disparate array of stylistic influences in reggae, neo-soul, Japanese manga, Chinese kung fu, space travel and political protest. The connection between disparate, seemingly unrelated elements is the key to Pacific navigation both as metaphor as well as a genuine historical practice — it’s how we found our way across the expanse of time and space and its ongoing importance to our many cultures cannot be overstated.

Te Moana Nui a Kiwa, the great ocean of the Pacific, is so large that you could fit every landmass on planet Earth within its bounds — every single mountain, every desert, every forest, every tundra, every swamp, the whole of the Outback, every inch of China, all of Europe, both Americas, the River Nile, the Amazon rainforests — the entire above-water surface of the planet. What we find in that enormous ocean instead is a small smattering of islands, separated by a shifting and living abyss of sea and wind. If we need an image for comparison, wait for a dark night and look upwards at a series of bright and tiny points separated by the mass of space. For thousands of years, our many peoples travelled from one tiny point in the Pacific to the next tiny point, developing the cognitive tools necessary to relate each destination and vector into a coherent whole. If we need an image for comparison, we can look at a map of astral constellations drawing invisible lines between random stars, revealing their connectedness to one another.

As it was for our navigating tūpuna, so it is for navigating Che. Reggae from distant Jamaica bears a strong relation to our Māori and Pacific lives — born from a tropical island nation under the rule of the British Empire, it speaks the story of its people and their resilience in the face of colonisation and its fallout. Che himself was raised in the Rastafari community of Auckland where the echoes of Haile Selassie harmonised with the prophets of Parihaka, of Ringatū and Rua Kēnana. The martial-arts films of Hong Kong introduced Che to the real-life folk hero Wong FeiHung, the great doctor and martial artist who stood against the colonisation of China, his kung fu the spiritual brother to our mau rākau. In hip-hop we find the language for dealing with an urbanised existence, where technologies are used to break music into small samples, rearranged from small parts into a cohesive and expressive whole. What we realise on reflection is that navigation itself is an identity, that the traversal and connections made are the work itself and ably performed on Navigator.

Back to 2021: we live in a present where a Māori cyberpunk video game is available on Nintendo, where rockets are launched from the southern tip of Māhia, and Taika Waititi will write and direct his own Star Wars film. We have world leaders in the field of indigenous data sovereignty exercising tino rangatiratanga over digital information and its applications. A renaissance in Māori arts has culminated in the massive Toi Tū Toi Ora exhibition at Auckland Art Gallery and the only twitter worth following is Poly twitter. We also have the persistent and indelible menaces of over-policing and cannabis criminalisation, which, from some dint of idiocy, remains a racist policy, while land remains in the greedy hands of the criminally undeserving. But whānau persists, whakapapa persists, and the cultural resilience and innovation expressed by Che Fu & The Kratez continue their journey from the past well into a future we’re yet to see.

Two decades is an eternity by one measure of time and the blink of an eye by another. As time resolves its orbit around this anniversary event, as Che Fu & The Kratez perform at Auckland Town Hall once more, we have the time and the tools to chart our movements into the future, given to us by an expert navigator.