Nov 16, 2017 Film & TV

The Killing of a Sacred Deer

Directed by Yorgos Lanthimos

????1/2?

Something is wrong. You will be a good way into the second English-language feature from Greek writer/director Yorgos Lanthimos before you know what, or why, or what will come of it, but the sense of something palpably amiss is pervasive and enveloping.

Calling this a horror film would be accurate in a technical sense, but also misleading. It lives out on the far cinephile fringe of horror, where creeping unease replaces the jump-scare. I’m divided between wanting everyone I know to see it — it’s a grand and memorable piece of art — and wanting to post warning notices at the door.

The first thing we see is a close-up of glistening raw flesh. It’s discomforting; for the squeamish it will be worse than that, but even for those desensitised by slasher films and hyper-realist medical dramas, the lack of context gives your mind too many places to go. The explicitness of the image is not typical of the film, which is far more interested in mental discomfort than body horror, but that brief moment of visual disorientation — are you seeing open heart surgery? An act of torture? The ritual killing of the title? — counts as fair warning.

We cut to two doctors walking down a hospital corridor. One of them is Colin Farrell, and their conversation has a distinctive tang which will be familiar to anyone who’s seen Farrell’s previous collaboration with Lanthimos, The Lobster. The earnest over-sharing of that film’s dialogue is back, but here it has a very different effect, and Farrell is playing a very different character: not a sweet no-hoper placed in a ghastly predicament by a satirically dystopian society, but a wealthy professional with a picture-postcard life in a society that seems identical to ours.

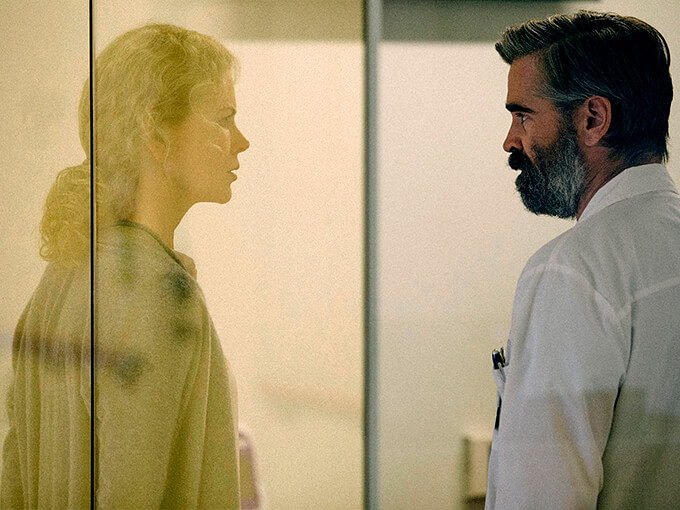

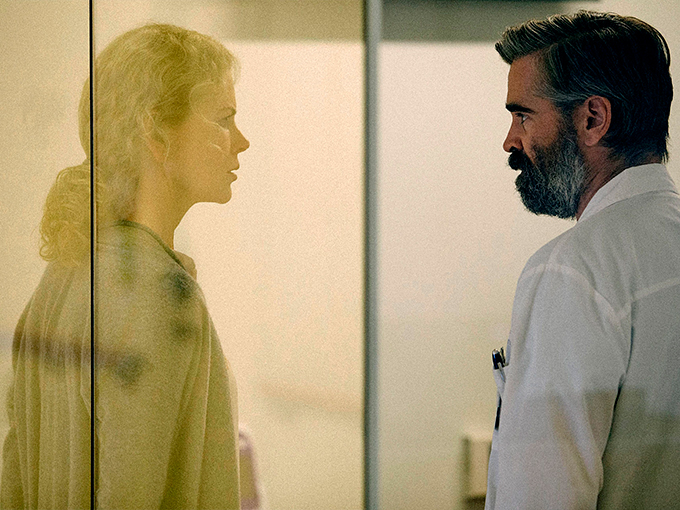

We get hints quite quickly that there’s something off about his relationship with his wife (Nicole Kidman) and something forced about his mentorship of a needy teenage boy (Barry Keoghan), but the stylised dialogue means that every conversation in this film feels a little wrong.

It could just be Lanthimos playing language games; it could be that these are ordinary people speaking a heightened cinematic dialect. Or it could be that the artificial vernacular is a form of double bluff. Maybe every relationship in the film really is subtly poisoned.

The soundtrack and the cinematography combine to reinforce the effect of the language, with jarring music cues and camera angles that defamiliarise and discomfort without quite rising to the level of overt manipulation.

The performances are equally well judged and equally ambiguous. It should not be surprising to anyone at this late date that Nicole Kidman can convey a complex inner life with one twitch of an eyebrow, though I’m still getting used to the idea that Farrell can match her. But the real surprise in the cast is Keoghan, last seen as a young fishing-boat worker in Dunkirk, and here a remarkably strong presence. Exactly where his character sits in the story takes a while to become clear, and the revelation is not a happy one. This is not, in fact, a happy film. But it reinforces my sense that Lanthimos is one of the most original voices in today’s cinema.

Opens November 16

This is published in the November- December 2017 issue of Metro.