Jul 24, 2017 Film & TV

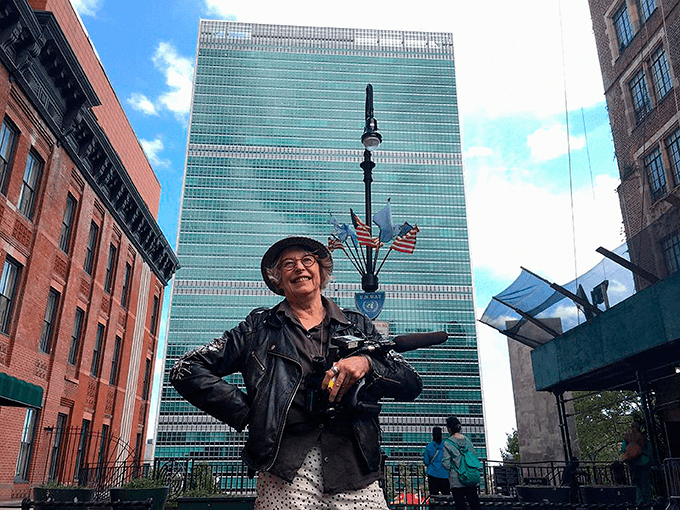

Tracking Helen Clark’s tilt for the top job at the United Nations, Gaylene Preston documented the creatures of the diplomatic world.

One remarkable thing about making her latest film, My Year with Helen, was that her subject could hardly have been more relaxed about letting her into the room… and yet the leprosy factor was still there, because for a lot of the filming, the room was owned by the United Nations.

“After Hope and Wire [Preston’s 2014 TV miniseries about Christchurch in the wake of the quakes], I think I had swallowed too much liquefaction dust and I got a lung problem. And that always makes you a bit depressed, you know? And it just seemed to me that everything was getting worse — the planet was melting, the world was in a terrible state. And at some point around then the thought struck me — why is Helen Clark so chirpy?”

As the head of the United Nations Development Programme, Clark was surely in a position to appreciate how terrible the state of the world was. And yet… she seemed to enjoy her job. In fact, she had just signed on for a second term. “I thought, she really must think she can make a difference. I’m interested in finding out how that goes. And so I rang her and asked her if I could make a film about the work she was doing.” Usually this would trigger a lengthy bout of negotiations, or a flat no. “But she just said yes. And I said, well, I’d want creative control. And she said, you’ve got it.”

So Preston went to Botswana, to watch Clark at work. “The Film Commission have got this great approach at the moment where you can test out a film idea by doing a little bit of work. So they funded a little crew of three of us to go to Botswana, where Helen had a visit scheduled, just to find out whether there was a film here. You know: What does the head of the UNDP actually do? Is it so invisible you can’t film it? Is it just people sitting around in meetings?”

It turned out to be considerably more filmable than that, though meetings were certainly involved; footage from that trip is in the finished film. Preston came back and set about securing funding for a full-length documentary. “We got money from the Film Commission on this complicated new plan where they give you half, and then you have to raise another quarter, and they’ll match that quarter. But when you get your initial half, you have to agree that you’re going to deliver the film regardless.”

Preston has been making independent films in New Zealand for nearly 40 years. “Basically, the work that I do, and have done since 1978, starts between my ears, and then I go out and work with others to raise the money to get the project onto the screen.” She found private investors and secured her budget, and set off to start making the film. There was just one little thing she didn’t know. “I think Helen knew from the beginning! But I didn’t. So yeah, it turned out the year we were following her around was the year she was running for [UN] secretary-general. Actually, Helen let us in at a very vulnerable moment. How would you like to be filmed doing a really big, drawn-out, semi-public job interview?”

“Semi-public”, Preston found out quickly, was a term whose meaning had to be negotiated day by day when it came to filming inside the UN buildings. “Once we got to New York, access was difficult. Because, A, these people are really busy. And, B, they’re really busy in rooms that it’s impossible to get a camera into, because of all the security restrictions.” These barriers were somewhat reduced for the initial debates among the candidates for secretary-general. “That first 2016 debate was a historic event. It’s the first time there have ever been cameras in the room for the General Assembly. Normally the way the secretary-general is appointed has been a secret shoulder-tap thing. The process is papal, basically. And, basically, it still was, despite everything they did to make it seem like the public was being allowed in. There was a Danish documentary being filmed that year at the UN as well… as the only two crews who have ever been in there making documentaries over a long period, we would sometimes get together on a Sunday, the Danes and the Kiwis, and complain about how hard it was.”

The debates made it seem the candidates who performed best at them — in particular, Clark — had a realistic chance of becoming secretary-general. As the year went on, this notion faded. “And when Helen didn’t get the job, everyone went, oh dear, I guess you haven’t got a film there.” But Preston and her crew had also been tracking campaigners lobbying to have a woman to lead the UN and filmed the press corps trying to work out what was going on in the contest.

“I see this film, and really I always did, as an ethnographic documentary. So the UN is the watering hole and the animals come through to drink, you know? There’s ones that arrive in the morning and ones that are there at night. The big animals come past… there’s the diplomats, the lobby groups, and there’s the press and the observers. Those are the principal tribes, and there’s a whole bureaucracy around keeping them separate. And when we went there, we were filming the gaps. We’re the unofficial version.”

This is published in the July- August 2017 issue of Metro.