Mar 29, 2023 Film & TV

In May, the Māori Television Service — or, in its current form, ‘Whakaata Māori’ — celebrates 20 years since its founding. As we approach that two-decade anniversary, it’s worth reflecting on the impact Whakaata Māori has had on New Zealand’s television and its public life, and asking what its future is in a media landscape that’s moving beyond linear television to multi-platform content.

In 2003, handing Māori control of our own television station was a bold experiment. It would not only be a medium for te reo Māori to enjoy greater use, but an opportunity for Māori to exercise control over all aspects of the production of news and other programmes, offering a truly Māori perspective on the world. It’s hard to imagine today, with Whakaata Māori now an established part of the New Zealand media, but in 2003, this was revolutionary.

The first iwi radio stations commenced broadcasting in the late 1980s. But they were — with the later exception of Radio Waatea — strictly regional, often with inadequate government or commercial funding. Te Reo Irirangi o Te Upoko o Te Ika, a Wellington-based station, broadcast its first show in 1987, yet had to wait another three years until New Zealand On Air agreed to offer funding. The Māori Television Service, then, was the first attempt at a fully funded national broadcaster.

Twenty years on, it seems natural and uncontroversial that there would be a te ao Māori-focused broadcaster, just as there are numerous broadcasters based in te ao Pākehā. But it nearly didn’t happen. The legislation to create Whakaata Māori passed by a thin margin. Conservative politicians opposed it, with the opposition National Party’s Katherine Rich telling Parliament, “I do not think this channel will have any role in preserving the language.” Rich’s colleague Murray McCully told the House it would be “held up to public ridicule”, while Act’s Stephen Franks simply called it “racist”, reflecting the sad worldview that media embedded in te ao Pākehā is natural and universal while te ao Māori is not.

But, despite the official opposition, the channel was warmly received from the outset, with viewership growing from 300,000 a month when the first broadcast went live in 2004 to 1.5 million by 2009. Five years in, the public had embraced Whakaata Māori, with 84% of New Zealanders saying it should remain a permanent broadcaster and 73% of Māori saying it made them feel proud of their country. It might be hard for non-Māori to imagine the impact that having a Māori television channel had — what a big deal it was and is for our people to hear Māori voices, see Māori faces and culture centred and treated as normal rather than as an afterthought or something ‘external’ to be seen through the Pākehā gaze.

The importance, too, of a broadcaster that uses te reo rangatira by default can’t be overstated. Language is the water that nourishes and keeps culture alive. As pioneering Māori broadcaster Dr Sir Haare Williams puts it: “We are a culture with a reverence for the finest art of all in the spoken word. The spoken word is sacred, as it defines mana.”

But it is not just Māori who enjoy Whakaata Māori’s programming. Today, 1.1 million New Zealanders watch Whakaata Māori each month, with 400,000 using its website. Audience engagement grew 11% last year. That is doing an immeasurable amount to grow understanding of te reo and te ao Māori — not just among Māori but among all New Zealanders.

Whakaata Māori has also been a training ground for many talented young Māori to learn their craft, both in front of and behind the camera. As Sir Haare put it to me: “Māori journalists see themselves as Māori first and journalists second, with a responsibility to respect and uphold culturally sanctioned practices like manaakitanga and kaitiakitanga. Unlike commercial and state-owned media, reo-Māori media are primarily agents of language revitalisation. In that world, reporters have to observe tikanga and the disciplines of journalism.

“The goal of Māori journalists must always be the pursuit of excellence, maintaining the integrity of re reo, and retelling our nation’s bicultural narratives. We are taking positive steps to tell and own our stories. Whakaata Māori is a key contributing factor in normalising the use of te reo and removing stigma associated with the language, therein supporting the linguistic identity of te reo speakers and those for whom te reo is a language of tribal heritage.”

That pool of extraordinary presenters, writers, producers and others has spread as they take their skills to other broadcasters and bring with them a confidence in telling stories in te reo and through a te ao Māori lens. One example is Annabelle Lee-Mather, who began her television career presenting the Māori-language news show Te Kāea when Whakaata Māori launched. She went on to create The Casketeers, the hit show following the team at Tipene Funerals. The Casketeers was revolutionary for combining the reality-TV format with te reo Māori, opening the door for Pākehā and international audiences (via Netflix) to Māori tikanga — especially in the context of tangihanga.

Lee-Mather says being able to tell stories on Whakaata Māori is different from her experiences at other platforms. “In mainstream, when you’re creating content, be it journalism or factual programming, you have to bear in mind that your audience may not be familiar with the issues, the ideas, the concepts, the kaupapa, the tikanga, the places that your story is about — you’re not just telling a story that is happening today, you’re giving a history lesson. The beauty of Whakaata Māori is you’re about to create much more nuanced stories and content, and have more space to delve into the issues. Imagine if you were a news reporter and [with] every story you have to explain the rules and history of the game — it would limit how deep you can dive into the actual story. Whakaata Māori allows us to go deeper from a storytelling perspective.”

Having a media voice that Māori know and trust is important for spreading knowledge and vital information as well as opinions and perspectives. As Minister for Broadcasting and Media Willie Jackson told me: “Māori media entities are highly trusted by Māori communities and are able to disseminate authentic Māori stories to audiences where trust and confidence in government and other authorities can be lower. Whakaata Māori played a critical role in serving Māori communities during the Covid-19 pandemic — including broadcasting the Super Saturday Vaxathon on its platforms, which saw an increase in Māori vaccinations. Similarly, we have seen the ability of Māori media to reach communities through the response to recent climate events in the North Island.”

Tellingly, 20 years after its contentious creation, no serious politician is talking about scrapping Whakaata Māori today.

But the future is looking complicated. One, for Whakaata Māori, and two, for all traditional television broadcasters. Each year, fewer and fewer people are sitting down and watching television ‘live’ as it’s broadcast. So-called ‘linear’ television is being displaced by a myriad of streaming services, video platforms and social media. The change from the old name of Māori Television to Whakaata Māori reflects that changing environment. The word ‘whakaata’, meaning to reflect or display, goes to the heart of the organisation’s purpose of displaying te reo and te ao Māori while removing the previous name’s link to just one type of media.

How will Whakaata Māori continue to reach audiences in this increasingly fractured media landscape? As Lee-Mather says, “You can’t get the rangatahi to come to you. You have to go to them.” It’s no longer about a single platform, but about reaching out across platforms, with tools like Te Ao Māori News, a news website mixing English and te reo, and the MĀORI+ app, allowing viewers to watch Whakaata Māori programmes at any time.

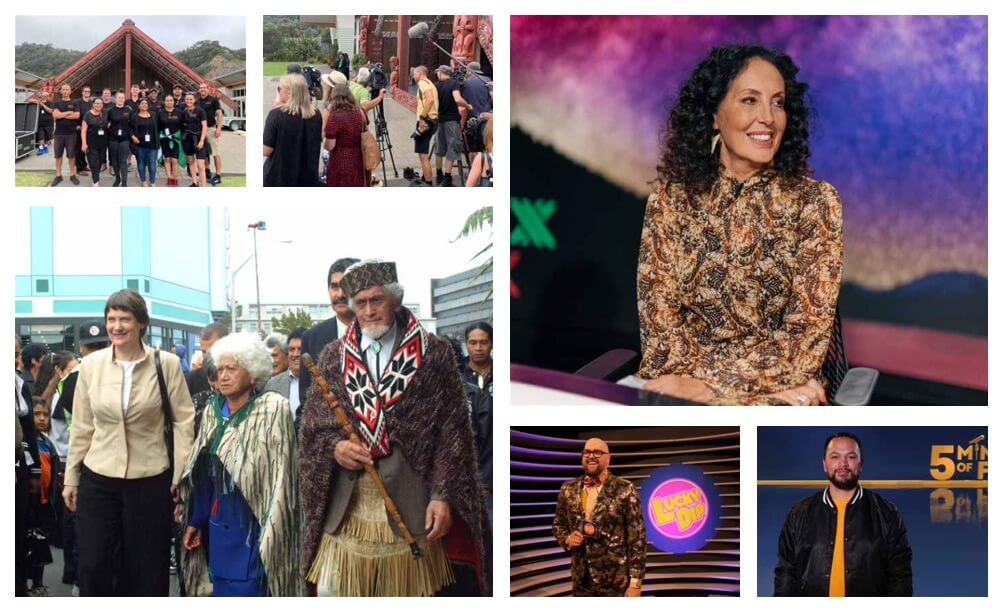

Images from the first 20 years of Whakaata Māori

Some commentators argue the internet age will be the death of traditional media organisations. But for Whakaata Māori, it could be a new birth, creating more ways of telling Māori stories and perpetuating Māori culture, both for Māori and all New Zealanders. One of my favourite Whakaata Māori shows is Te Ao with Moana, which covers national and international stories through a Māori lens. It’s broadcast at 8pm on Mondays and the live, linear audience probably isn’t huge these days, but its largest audience is via Facebook, where it has 124,000 followers and some of its stories have been watched by over a million people.

The problem is, Facebook views don’t pay the bills. There’s a danger that Whakaata Māori, which has been able to back so much innovative programming and employ young talent to bring them up the ranks, won’t be able to do so under the new media models.

Minister Jackson told me the government is looking at ways to ensure the financial viability of Whakaata Māori in this new age, and giving it the flexibility to adapt the content it provides to evolving media platforms: “The government is exploring a move to directly fund Whakaata Māori for content production, which will reduce complexity and provide greater surety of funding for Whakaata Māori”.

To understand the change that would be, you need to understand the history. From the 1970s to the 1990s, successive governments dramatically restructured the state broadcasting sector, carving off TVNZ and RNZ from the old New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation and redistributing a part of that entity’s programming funding. Under the new system, any broadcaster or programme-maker could apply to New Zealand On Air (and later Te Māngai Pāho) to fund the production and distribution of their shows. Theoretically, that meant private-sector broadcasters could compete on an equal footing with public broadcasters. Many of the shows that Whakaata Māori runs are not directly funded through the station, but rather via Te Māngai Pāho or New Zealand On Air. Jackson’s exploration of direct funding would upend that 30-year-old funding model.

The government also hopes, Jackson told me, to “modernise” the legislation governing Whakaata Māori which “currently risks limiting audience growth and the delivery of innovative content, as well as hindering cooperation with other media entities”. In 2016, the then Minister of Māori Development, Te Ururoa Flavell, amended the Māori Television Service (Te Aratuku Whakaata Irirangi Māori) Act empowering Te Mātāwai, the statutory entity responsible for promoting the health and wellbeing of te reo Māori, to appoint four of the station’s seven directors. Ministers appoint the final three directors, giving Te Mātāwai the more important stake in governance. This structural change, some critics argue, means the station relegates programming in English in favour of programming aimed solely at language revitalisation.

“Whakaata Māori has always operated in a challenging environment that requires it to meet obligations to Māori language and culture while also adapting to changing technology and audience preferences in a competitive media system,” Jackson says. “Whakaata Māori has grown from a broadcaster of a single television channel to a multi-channel and multi-platform provider of content that audiences can access anywhere, any time, on any device.”

Anyone who tells you they know the future of media platforms is fooling themselves. Look how much things have changed in the past 20 years, and how existing media outlets have been able to adapt and change with new technology. People once envisaged digital media as being like a newspaper but on a computer screen, not the social media platforms compiling stories from many outlets and serving up individualised offerings according to what algorithms think are our interests.

We don’t know where technology will take us next — how it will actually be utilised and how it might change our lives is too hard to predict. Who knows what the next 20 years will bring for Whakaata Māori? But we know Whakaata Māori is a taonga worth preserving and growing. It has been a pillar of the revitalisation of Māori language and culture, and introduced Pākehā to the richness te ao Māori has to offer.

In testament to this work, Sir Haare gives me a poem, ‘Kōtuku Rerenga Tahi’:

Ngā kōtuku rerenga kōrero e iri nei

Kua tuituia ki te korowai o te kōrero

E kore ona wai unuroa e mimiti noa

E takatū nei te hunga kua mahue

Kia tere te karohirohi mō te katoa

Like the kōtuku of a single flight

Stitched together the power of the word

Nor will their spring waters diminish

For those thirsting to sip its nectar

To lift off and soar

As he explains, “The sacred white heron is seen once only in a lifetime and, like angels and our children, we don’t know they’ve been until they’re gone. And when they’re gone, they leave a lasting legacy for those that follow. This poem is a tribute to those with the courage, fortitude and resolution to establish a voice for Māori in the media.”

Twenty years ago, I watched as critics accused a Māori television station of being a pet project — a money pit that no one would watch. They didn’t see the huge latent demand among Māori for programmes that spoke to them. They didn’t see the richness that would be added to New Zealand’s culture and language by having a station that is devoted to the Māori worldview and serves as a training ground for young Māori to enter into broadcasting. They didn’t see that many Pākehā would embrace Māori-based programmes with a Māori perspective. As we look forward to what’s next for Māori broadcasting, following the soaring flight of the white heron that came before, we can do so with the confidence and experience that Whakaata Māori has given us.

–

This story was published in Metro N°438.

Available here.