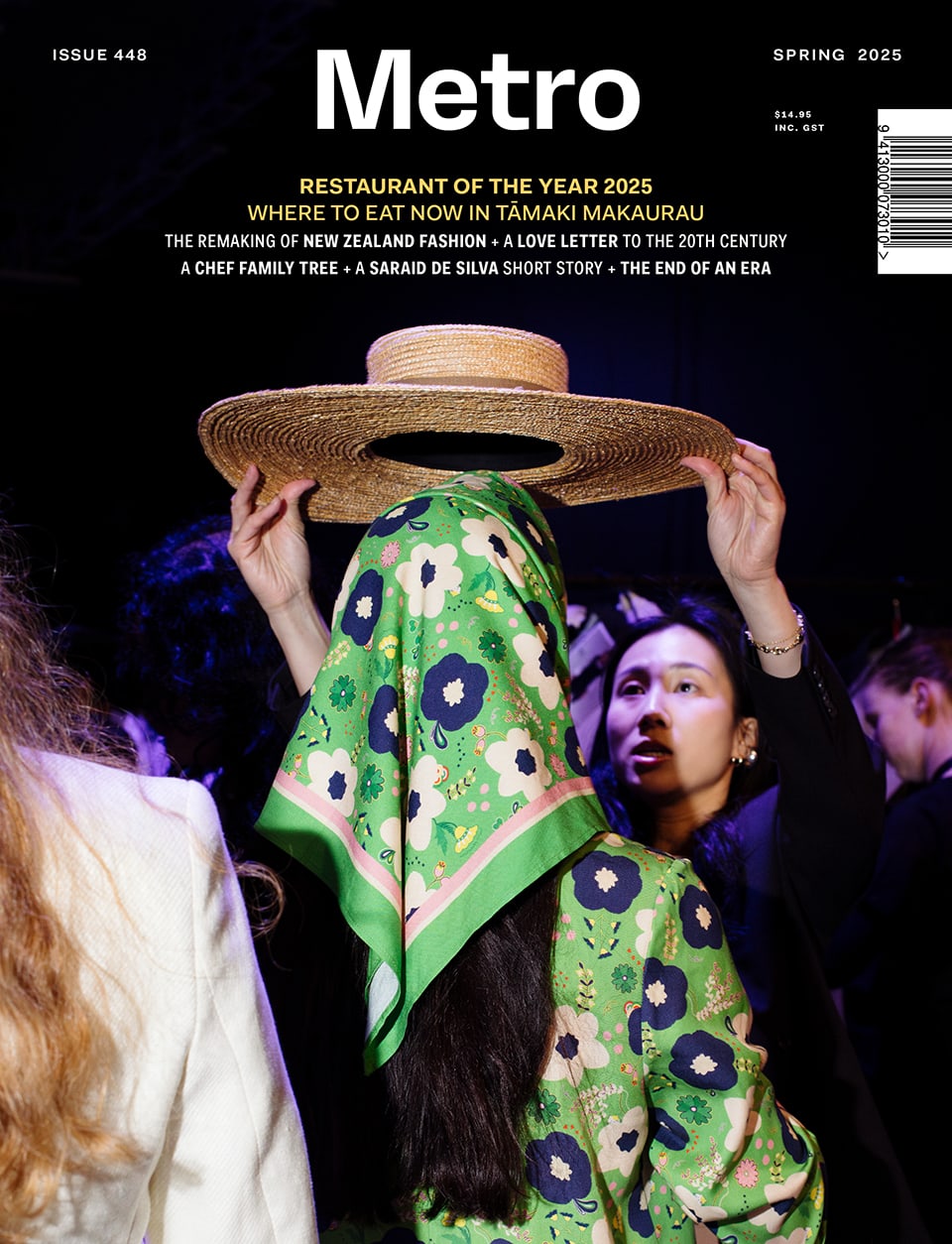

Mar 7, 2013 etc

Forget what they say in Wellington, the creative capital of New Zealand is Auckland. Simon Wilson wonders why it’s taking us so long to wake up to the fact.

Photographs by Charles Howells and Jeremy Toth. First published in Metro, March 2009.

“Oh the shark has pretty teeth, dear, and he shows them pearly white…”

If you know the song “Mack the Knife” from Louis Armstrong or the mid-century Broadway recordings, you know the comfy version. The singalong one. But if you know it from the production staged in Auckland last year by Silo and the Large Company, you know something far more dark and dangerous.

Silo presented Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s classic The Threepenny Opera using a 1990s adaptation, written in the wake of the first Gulf War. Gangsters were not romanticised. Politics was nasty. Brutality, insisted the play, infects everything it touches.

It was gritty, classy, provocative, thrilling. And almost operatically large-scale: director Michael Hurst had 27 people crowding the Maidment stage. Right now — this is a personal view — there are only two theatre companies in New Zealand capable of staging a work that big, that challenging, that assured. Silo is one. The Auckland Theatre Company (ATC) is the other.

In fact, Wellington’s Downstage Theatre presented the play way back in 1988, using the earlier, senti-mentalised script but in an edgy, stylish production. The director was Colin McColl. These days, sadly, Downstage is in such disarray it is in serious danger of losing its Arts Council funding. And McColl is now an Aucklander: he’s the artistic director of the ATC.

The arts are not dead in Wellington. Of course not. But their epicentre is Auckland. Most of the leading work is here. Most of the leading practitioners, if they were not born here, have made the move.

In 2005, Auckland City had 13,616 people working in the creative sector. Wellington had 4540. The Auckland total represented 5.1 per cent of the city’s population; in Wellington it was 4.1 per cent. The cities with the next highest percentages were Manukau and then North Shore (the figures are from an Auckland City Council report called “Snapshot”).

Auckland also has more cultural institutions than Wellington, more events and much bigger audiences. Most cultural industries are based here; most of the work is here. And the gap between the two cities, on every one of these measures, grows wider every year. It’s all over, bar the shouting.

But there is such a lot of shouting. Wellington, says Auckland Art Gallery director Chris Saines, is very good at being the “leader in brand recognition, leadership and public relations”. They know how to talk about themselves. As Christchurch is the Garden City and Taihape is the Gumboot Capital of the World, so Wellington is supposedly the Culture Capital — even though Auckland has more culture and, for that matter, more gardens, and probably more gumboots too.

If you say it often enough, you can make it so, and Wellington Mayor Kerry Prendergast, like every one of her predecessors in the past 30 years, never misses a chance. Saines: “By brand, I don’t mean a friggin’ logo. I mean a reputation.” Prendergast knows that reputat- ions rely on the rap.

It’s easy to reduce the argument about reputation to clichés: Auckland does tits and teeth; Wellington is all beards and berets. And yes, there are more, um, teeth on show here; and yes, when you walk down Wellington’s Cuba St, you have to fight your way through a forest of facial hair. Samuel Flynn Scott and Luke Buda will have to answer for that one day.

But we have Liam Finn and they had Carmen, so the reputations of both cities are a little misleading. More pertinent is the real reason Prendergast talks the talk: Wellington would absolutely positively die if she did not.

Take the World of Wearable Arts (WOW), which shifted from Nelson to Wellington four years ago. Was that the big bully stealing lollies from a smaller child? Not at all. Wellington desperately needed WOW. Despite its reputation it has almost no unique major arts events.

One thing Wellington does have is individual cultural giants: Peter Jackson and Richard Taylor in film, Ian Athfield in architecture, creative writing professor Bill Manhire, the irrepressible dancer Jon Trimmer and the country’s pre-eminent art dealer, Peter McLeavey. But compared with Auckland, the ranks behind them tend to be much thinner.

What it also has are an excellent arts festival and many national organisations, mostly funded by central Government: the Symphony Orchestra (NZSO), Creative New Zealand (CNZ) and New Zealand on Air, the Film Commission, the Book Council and the Booksellers Association, Choirs Aotearoa New Zealand, the New Zealand Ballet. It even has Toi Maori, which funds Maori visual arts nationally, most of which, of course, are north of Taupo.

In the past 20 years, though, most other cultural organisations — the ones more openly exposed to the winds of commerce — have made the shift. Very few publishers (books, newspapers and magazines) remain in Wellington; the advertising industry has shifted north; so has television; and so, despite Jackson and Taylor, has much of the film world. The major celebrations of Asian culture, from the Lantern Festival to Asian hip-hop clubs, have emerged here. As for popular music, the visual arts, literature, architecture, design, dance, crafts, fashion and everything Maori and Pacific, they were always strong here. And the latest nail in the coffin for Wellington? Auckland is now the centre of theatre as well (see page 34).

Actor and director Cameron Rhodes is from Wellington but he lives here now. “Wellington was claustrophobic. This is where the work is, and the pay is probably a bit better too.”

Auckland-born actor and singer Madeleine Sami — star of our cover shoot — says: “Some of my friends, they go back to Wellington and they reckon there’s no one there any more.” Writer Stephanie Johnson, a sixth-generation Aucklander, sees the flipside of that. In Auckland, she says, she is often the only locally born person in the room.

It’s not just the artists: Auckland attracts the administrators too. David Inns has just resigned as long-standing CEO of the Wellington Arts Festival to become CEO of the Auckland Festival. The Auckland Museum lured its all-important “head of delivery” Tim Walker from the NewDowse in Lower Hutt, and the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra (APO) got its CEO, Barbara Glaser, from the best orchestra in Australasia, in Melbourne. The general director of New Zealand Opera, Aidan Lang, turned his back on Glyndebourne and a successful European career to live in Auckland.

Sooner or later, almost everyone comes to Auckland. Colin McColl, who is now New Zealand’s pre-eminent stage director, probably speaks for many: “I don’t know if I could ever live back in Wellington. But I love visiting.”

So why does Auckland have such trouble accepting its cultural status? “Auckland has an inferiority complex,” says Nick Bollinger, a musician and Radio New Zealand rock critic who moved here from Wellington three years ago. An inferiority complex, in such a brazen town? Really?

The thing is, in the past Auckland has been so adept at Philistine behaviour, one might think it was deliberate. Some of that continues; much of it does not. But it’s been instrumental in making Aucklanders think so little of their creative selves. That inferiority complex begs many questions…

Does the weather cause bad habits?

“In this city,” says Rosanne Meo, chair of the APO, “if you make your $100,000 and you’ve got your three Bs — you know, boat, bach and Beemer — you’re happy to leave things be.”

Indeed, for the rest of us as well, at home on a sunny evening with the other three Bs — backyard, barbecue and beer — we might think, “I could go to a show tonight”, but we’re not likely to do anything about it. The day’s still warm, the beer is cool, and the traffic’s a menace: why would you go out?

Actually, adds Meo, “it’s a poor excuse”.

That’s true. Spain is not a country of Philistines, but they have hot weather and beaches. In Tuscany and Provence, they do not allow the delights of the Garden of Eden in which they reside to keep them from the opera. And though Europe has hundreds of years of good cultural habits to call on, Brisbane doesn’t. It has spent the past 10 years turning itself into a creative city, despite the heat.

McColl: “Brisbane used to be awful, but they’ve got it together now. They’ve developed the whole South Bank area, there are art galleries, cafes, theatres. It’s just pumping.”

Greg Innes, CEO at The Edge, also points out that Melbourne was almost a culture-free zone 20 years ago.

It’s not easy to change bad habits, but it’s happening — particularly through the schools. The ATC has “ambassadors” in every high school in Auckland, and its regular school nights last year were sold out for the whole year within four days of being announced.

“Theatre is not bizarre for young people,” says Cameron Rhodes, “because they study it. The kids at the ATC forums have a huge knowledge of theatre.”

The APO has a programme for low-decile schools in Manukau, based at the TelstraClear Pacific Events Centre. It sold out within five hours. “We have another programme called Remix,” says Meo. “We take 20 kids for a week. Most of them have never seen an instrument before. They just love it.”

Madeleine Sami, who went to Onehunga High, says schools are “full of amazing music and drama teachers”. That’s where she learned her stage skills, along with Theatresports and the Maidment Youth Theatre.

Last year, Silo Theatre moved out of its premises to play in bigger venues. It was wildly successful, says Silo board member Jennifer Ward-Lealand, and the biggest audience growth was in the 18-35 age range.

With generation change, they all believe, the Philistines are on the run.

Is it the history?

Little-known fact: Auckland had an arts festival from 1948 until 1982. David Malacari, the artistic director of the Auckland Festival, has all the old programmes. The last one is instructive: it’s a cheaply produced affair resembling the efforts of a 1950s English repertory company to congratulate its luvvies for being so lovely.

But the arts in Auckland at that time were not rotting in a backwater. This was four years after Limbs turned dance on its head and one year after Greg McGee released Foreskin’s Lament into the world. Both were from Auckland, but as that programme revealed, the excitement they generated was lost on the festival planners. No wonder it folded.

Four years later, Wellington stepped forward with its own New Zealand International Arts Festival. Note the name. If you say it, that makes it true.

Worse was to follow. In 1986, Theatre Corporate folded, and Mercury Theatre followed a few years later. The Watershed sprang to replace them, but when the Viaduct rebuilding programme began, it too had to close.

Meanwhile, all over the Western world, the 1980s signalled the start of a great period of urban renewal, and not just in the arts: cities put up sports stadiums, made over their waterfronts, built new museums and performance centres and recreational venues. Baltimore, Vancouver, Melbourne, Singapore, London, Glasgow, Wellington… but not Auckland.

Michael Hurst, then on the Watershed board, says they pleaded with the Auckland City Council to put a performance venue into the Viaduct, and were told not to worry, the whole area was going to become an entertainment precinct. “What a laugh that was.”

Which is why Auckland has the reputation of a Philistine city, and why Wellington was able to assume cultural leadership.

But there was also a counter-history. Artists didn’t stop doing their thing, and in late 1999 the city’s cultural outlook became a whole lot brighter: the Civic, magnificently saved from the wrecker’s ball, reopened.

It’s true the St James remains derelict; true also that in the same period Wellington managed to restore not just one historic venue, but three (its own St James, the State Opera House and the Embassy Theatre). But new life for the Civic proved, despite all, that Auckland was a city where things were possible.

It already had its own annual Writers and Readers Festival and more was to follow. Neil Finn brought Johnny Marr and friends to Auckland in 2001; the Walters Prize was inaugurated in 2002; and the arts festival was relaunched in 2003, with core funding from the same city council that once believed bars and restaurants constitute an entertainment precinct. The future of the APO was secured in 2004, the Vector Arena opened in 2007 and Q Theatre gained funding approval in 2008.

Madeleine Sami has her own way of charting the changes. “I started in 1998 at Silo, in Toa Fraser’s play Bare. I wasn’t really paid.” Now she makes a living from her work.

Is it the talent drain?

Auckland is not New York. If you’re an artist, Auckland is probably not the centre of your world.

“I’ve been to six farewells this summer,” says Cameron Rhodes, “young actors heading off. If you’re good enough you go.” Jennifer Ward-Lealand says the problem is largely confined to young single male actors, but that’s just in theatre. Film directors also head overseas, often as soon as they’ve made one movie. Rock bands give it their best shot all the time.

This definitely is a problem for Auckland, and it’s a permanent one: who would want to hold an artist back from seeking fame and fortune or even just inspiration in the world?

But if Auckland is a staging post, it can still do what staging posts used to do in other spheres: be a bustling, challenging, risky, frontier town. Have a festival and touring shows that astonish their audiences. Expect the local performers to be adventurous and highly skilled, to test their mettle before heading into the unknown. Make the place so stimulating that those who go will remember it, and yearn for it, and one day come back.

At the Basement, Charlie McDermott and his team understand this, with a popular programme of innovative and experimental work last year in the old Silo premises.

Greg Innes at The Edge also understands it. He runs the council-owned venture that includes the Aotea Centre, Aotea Square, the Town Hall and the Civic, and he’s busily trying to turn it into the leading performance centre in Australasia.

To this end he’s bringing in world-class shows like the April tours of The Cherry Orchard and The Winter’s Tale that no one else in Australasia will get. He’s also setting up regional tours, like the 2007 visit of the Royal Shakespeare Company. “We put together that tour for Asia and Australasia.”

Last year, Priscilla, Queen of the Desert played better here than anywhere in Australia, in the process proving its worth for a European tour and helping European promoters see the value of the Auckland market. The Auckland City Council, says Innes, is very supportive. “They underwrote Priscilla, you know. Didn’t cost them a cent, but we took 100 per cent of the risk of bringing that show here.” It’s much the same with the forthcoming My Fair Lady.

The grand plan is to initiate shows that tour. If that happens, standards will fly — and a lot of money will flow. “Sooner rather than later,” he promises.

Are we the wrong size? The wrong shape?

Chris Saines thinks of Wellington as being like a small Italian town. “The hills descend to a main piazza, it’s like an amphitheatre, and it’s very cohesive. Easy to get around. It’s like Sienna.”

Nick Bollinger says that in Wellington it doesn’t matter where your home is, “you do your living in the city. Here, it’s bigger, and you live in your local village.” Bollinger is in Pt Chev; if he goes to a movie, it’s probably at St Lukes. In Wellington, he used to head for Courtenay Place.

This is a common view. But Auckland is the same size as Brisbane, Vancouver and other cities that have become cultural centres, and it has the same potential for creating a cultural heart. It’s not the insuperable problems of transport or geography that keep people in their local Auckland villages, simply the perception that there are not enough reasons to leave them. People who want the Viaduct the way it is, after all, don’t have any trouble getting there.

Are we ignored?

It is odd that New Zealand On Air, with its crucial funding roles for two industries that are almost entirely based in Auckland (television and popular music), is still located in Wellington. Odd also that so much of Radio New Zealand still emanates from Wellington. And many people are convinced that funding for the arts is disproportionately weighted in favour of artists the funders can see right in front of their faces.

But essentially this argument is a red herring. So we don’t have most of the arts bureaucrats living among us? Well, maybe we’ll take that one.

Where are the champions?

Kerry Prendergast is a great champion for the arts in Wellington. So is Peter Jackson.

In Auckland, it’s harder to pick the public champions. Bob Harvey in Waitakere does well, but Waitakere is a sideshow. The artists — Neil Finn, Douglas Wright, Colin McColl — keep their heads down. Writer and commentator Gordon McLauchlan gets antsy on behalf of the city, but is a lonely voice.

It’s a problem. If you say something often enough, you can make it so. But who is going to do the saying? The new improved version of John Banks supports the arts, but with the best will in the world he is never going to be their natural champion, and nor is his cultural committee chairman, the soldier Greg Moyle. Somebody else will have to step up.

Related to this, there’s another thing Wellington does very well: it celebrates its champions. The likes of Jon Trimmer and writer Fiona Kidman are cherished. It’s not clear that our own arts champions — Finn, Wright, C.K. Stead — are similarly treated here.

Does business care?

There’s a bunch of business people and philanthropists in Auckland who keep the city’s arts afloat. Some of the names are well known: Jenny Gibbs, James Wallace and Robin and Erica Congreve are leading patrons; Rosanne Meo at the APO and Kit Toogood at the ATC lend their time and expertise to running boards.

One mark of their significance, and of Auckland’s leadership, is apparent in the mess Downstage has got itself into in Wellington. It’s obviously a breakdown in working relations between the theatre’s board and Creative New Zealand, and it’s the sort of thing that these days is almost inconceivable for a leading arts organisation in Auckland. Meo and Toogood simply would not let it happen.

But there are other problems. The first is that the number of patrons is small. Greg Innes at The Edge: “We don’t have the tradition of arts philanthropy you get in America or even Australia.” He puts it down, in part, to the fact we did not inherit the European tradition of cultural support. “Maybe it’s because we got the Protestants,” he says, “while they got the Catholics and the Jews.”

New Zealand Opera’s Aidan Lang points out that recent tax changes make it easier to give money to the arts. They’re rolling out a new fundraising campaign.

The second problem is that the number of business leaders who sit on the boards of arts institutions is also small. Meo: “About the only time you see prominent business leaders is when they are invited to opening night.”

More seriously, she says, the philanthropists and board stalwarts are not getting any younger and the next generation seems even less interested. These things point to problems ahead.

Do we have a heart?

In a way, this is what it all boils down to. In Wellington, you stand at the water’s edge by Te Papa, looking across to the spires of the wooden Para Matchitt bridge, reading the poetry set into the wharf. Around you, as well as the national art museum, there are several open-air amphitheatres, a theatre, the city art gallery, many public sculptures, the main public library and a boutique multiplex. Whichever way you walk, in just a minute or two you can find yourself a decent cup of coffee. You are in the middle of something, and you know it.

It’s worth noting: they showed political bravery to get all this. They moved the museum out of its much-loved Georgian building on a hill and resited it on the waterfront. They dug up a park and turfed the library out of its home — also a much-loved building. They connected the waterfront to the city with a footbridge so idiosyncratic, it never would have passed contrarian public scrutiny if Wellingtonians had been asked about it beforehand. They had the vision thing.

Though not wholly. In a remarkable piece of irony, the committee in charge of Te Papa, chaired by former prime minister and unabashed Philistine Bill Rowling, rejected the designs jointly proposed by Wellingtonian Ian Athfield and the world’s best museum architect, Frank Gehry. That decision cost Wellington the chance for a world-class building on its waterfront, and instead gave it a monolithic eyesore designed by Jasmax — an Auckland firm.

And yet it turns out hardly to have mattered: the crowds came anyway and continue to do so to this day. (In a further irony, Te Papa was signed off by the Cabinet in 1992, and John Banks, then Minister of Police and now Auckland mayor, says proudly he was the only dissenter. Not because he wanted a better architect; he didn’t want to spend the money at all.)

So what about Auckland? The APO held a function recently on the Spirit of New Zealand, which cruised the inner harbour and the Viaduct. “We had four trombonists on board, playing up in the bow,” says Rosanne Meo. “Can you imagine how wonderful that is, pulling in at the bars and restaurants? That’s the sort of stuff that will make Aucklanders passionate.” She wants an arts quarter established on the waterfront.

Greg Innes completely disagrees. “Auckland already has an arts quarter. Now we need to make the most of it.” He’s talking about the Aotea Precinct, a concept that includes SkyCity Theatre, all of The Edge, the proposed site of Q Theatre behind the Town Hall, the library, the art gallery, the design school at AUT and the Maidment at the University of Auckland.

Meo: “I’m worried about how you would make Aotea work, because Aucklanders’ whole preoccupation is with the foreshore. I suspect we need to go to the next phase.”

No, says Innes. “To re-establish what we’ve got here on the waterfront would cost at least $2 billion. How will that ever happen?”

Stephanie Johnson and Nick Bollinger tend to Meo’s view. Johnson reckons Queen St, including the Aotea Precinct, is “enough to make an Aucklander cry”. Bollinger adds that if they really want to make an arts quarter around Aotea, the atmosphere will require some attention. “They’ll need to find a way to slide K’ Road down the hill.”

But Chris Saines, who advocated successfully to rebuild the Auckland Art Gallery on its existing site rather than move to the waterfront, says he is “really excited” about the current redevelopment of Aotea Square. He’s also looking forward to the renovation of streets in the precinct. “I’d like to think that people might spend the afternoon at the gallery, head into Lorne St or close by afterwards and have a drink and a meal, and then catch a show at one of The Edge venues. That sounds like a good night to me.”

Aidan Lang looks out his office window on Mayoral Drive, across the Aotea Square building site to the SkyCity cinema complex, and isn’t nearly so confident. “Having the cinemas there is fine, but we’re looking at the back end of the building. They don’t even open onto the square. It’s the same with the Town Hall. And look at the Aotea Centre itself. Its façade is its Achilles’ heel. There are no cafes, no bars or restaurants.

“There is nothing here that makes me think the Aotea Square is the heart of something, that this area is an events centre.”

The current council is aligned with Greg Innes’s vision, sort of. But it scrapped former mayor Dick Hubbard’s big plan to realise an arts quarter in the area, and the current makeover of the square does not address any of the issues Lang is talking about.

This is a tragic debate. Both sides are right, and both will have to be accommodated. It’s preposterous to suggest abandoning the Aotea Centre, the Town Hall, the Civic and the refurbished art gallery. And yet as long as there is a waterfront, people will want to be on it. It’s equally preposterous to suggest the foreshore should not be enlivened by creative activity.

So Auckland will probably never have a unified arts quarter, like Brisbane, like Vancouver, like Wellington. But the two areas can both be made to work. The requirements have been itemised in many a submission: Auckland Theatre Company needs a home with a 600-seat theatre; mid-size touring acts (including music) need a 1000-seat venue; the APO needs rehearsal rooms and the city could do with a contemporary exhibition space that complements the art gallery, the way the Tate Modern complements the Tate in London. And don’t forget the Auckland Museum: they need to find a way to get themselves into the life of the city, too.

Yes, it’s a shopping list. But they have to start somewhere. Step one: someone has to impose a vision. That someone has to be the new council, however it is configured, which arises from the forthcoming report of the Royal Commission on Auckland Governance.

Here’s the need, in a nutshell: At the end of May last year, three big shows opened in Auckland: La Bohème at the Aotea Centre, Priscilla at the Civic and The Threepenny Opera at the Maidment. All three were critical and commercial hits. Night after night, the “arts quarter” was filled with thousands of people excited about their big night out. But did they feel part of something bigger? Probably not. Did they eat in the area first or have a drink there afterwards? Almost certainly not.

On the bright side, Rosanne Meo says more councillors than ever before now go to APO concerts. From both political sides? “Yes.”

When will we believe?

Why does one city believe it is a creative centre while another does not? Aidan Lang believes there is “no logic to it”. You just have to get on.

David Malacari at the Auckland Festival has a long-term view. “The most exciting thing about Auckland is its growing multiculturalism. I think the fruits of that are still some years away.”

Jennifer Ward-Lealand says times have been tough. “We lost our theatres, we took all these body blows, and it’s taken us ages to recover.” But, she adds, “I do feel Auckland is a city of culture. I think Aucklanders believe it too. I think it’s a myth that we’re not.”

The people who don’t believe it, according to Rosanne Meo, are the business community. And that’s a problem in more ways than one.

Greg Innes at The Edge: “We sold more Priscilla tickets to visitors from Hawkes Bay than Waitakere. Sold more in Dunedin than Waitakere, for that matter. They came in busloads from all over the country.” And they stayed in hotels, ate in restaurants, shopped in the CBD and Newmarket and took in the tourist sites.

That’s why it was stupid not to put a performance venue in the Viaduct when they built all the bars and restaurants. The arts are good for business.

There is also the Nokia question, which is: if Finland can create a company as globally successful as Nokia, how can we do it too? The answer was spelled out in 2002 by American writer Richard Florida, who argued that cities need a strong creative sector in order to be strong economically. If you want the best people to come and work for you, he wrote, you have to offer them the best — the most stimulating — environment in which to live.

Adventure tourism, beaches, bars and restaurants, good transport and, crucially, lots of stimulating arts. In Brisbane and Melbourne, business appears to understand this. In Auckland, it seems, not yet.

This may change. Aidan Lang met a man from Brisbane, in town with his wife to decide if he would accept a job offer here. They went to the opera: Lucia di Lammermoor, which contains all sorts of coloratura trills. It’s the sort of opera that, if done badly, makes the audience laugh at the soprano. But the visitors from Brisbane loved it. They decided that a town capable of putting on opera this good was probably a town worth living in, and the man took the job — as an executive in the transport sector. That’s right, “infrastructure” also needs the arts.

Maybe all the people in Auckland who get to make the big decisions on these things should troop on up to Illicit on K’ Rd and get a nice artistic tattoo on their foreheads, mirror-image so they see it often through the day. It would read: i live in the creative capital. the arts are good for business.•