Nov 11, 2016 etc

Back in the 50s, teenaged concert promoter Phil Warren breathed new life into Mt Eden’s Crystal Palace Theatre. Now his nephew is among a group of young musicians behind the art deco building’s second revival.

Buses fly by, people walk their dogs, but few Aucklanders are probably aware that a historic gem sits right there. Despite its modest entrance, the Crystal Palace Theatre still stands proud, and it’s a building that deserves a nod of recognition, not only because it’s a relatively untouched piece of the city’s heritage, but also because it’s now having a second life as a keystone of Auckland’s creative community.

Over the past two years, those art deco glasswork doors have opened out across the tiled floor once more, and slowly but surely have begun to usher in a new generation of music lovers.

She’s a little tattered and torn in places — as you walk down the aisles you may notice the odd creaky red seat, a cracked light fitting, or shabby carpet — and there’s a few cobwebs way up high, as well as an intimidating trove of reels of film, old microphone stands, and movie posters stored backstage.

But the Crystal Palace has proved to be the perfectly eccentric yet wondrously grand place to host some of Auckland’s most memorable live music gigs in recent memory. When Liam Finn, Lawrence Arabia and Connan Mockasin performed there in April with special guest Mick Fleetwood, who was here on holiday, much crowd euphoria and wild dancing ensued.

There was a similarly celebratory air at Arabia’s album-release party in July, punters dancing in the aisles as plastic cups gently rolled down the auditorium and people marvelled at the intricately moulded ceiling, complete with sea shells.

Marlon Williams’ old-world voice and sharp-suited style were particularly well matched to the scalloped curtain backdrop and art deco flourishes. But it was Hollie Fullbrook, aka Tiny Ruins, who kicked off the re-awakening of the Crystal Palace with her show in June 2014.

“It’s like Berlin, where there are lots of abandoned spaces and places, and they’re where all the coolest stuff happens,” she says. “There’s something about a slightly derelict space that gives you more freedom and vision.”

There’s a certain amount of gravitas attached to playing there, too. It’s a seated theatre, with its own beauty — albeit somewhat faded — which draws attention. And it’s one of the only theatres in this city which remains economically accessible to most of the local music community.

It’s also a place with much nostalgia attached to it, which looms large in the memories of many Aucklanders, and is in use once more because of a particular confluence of circumstances.

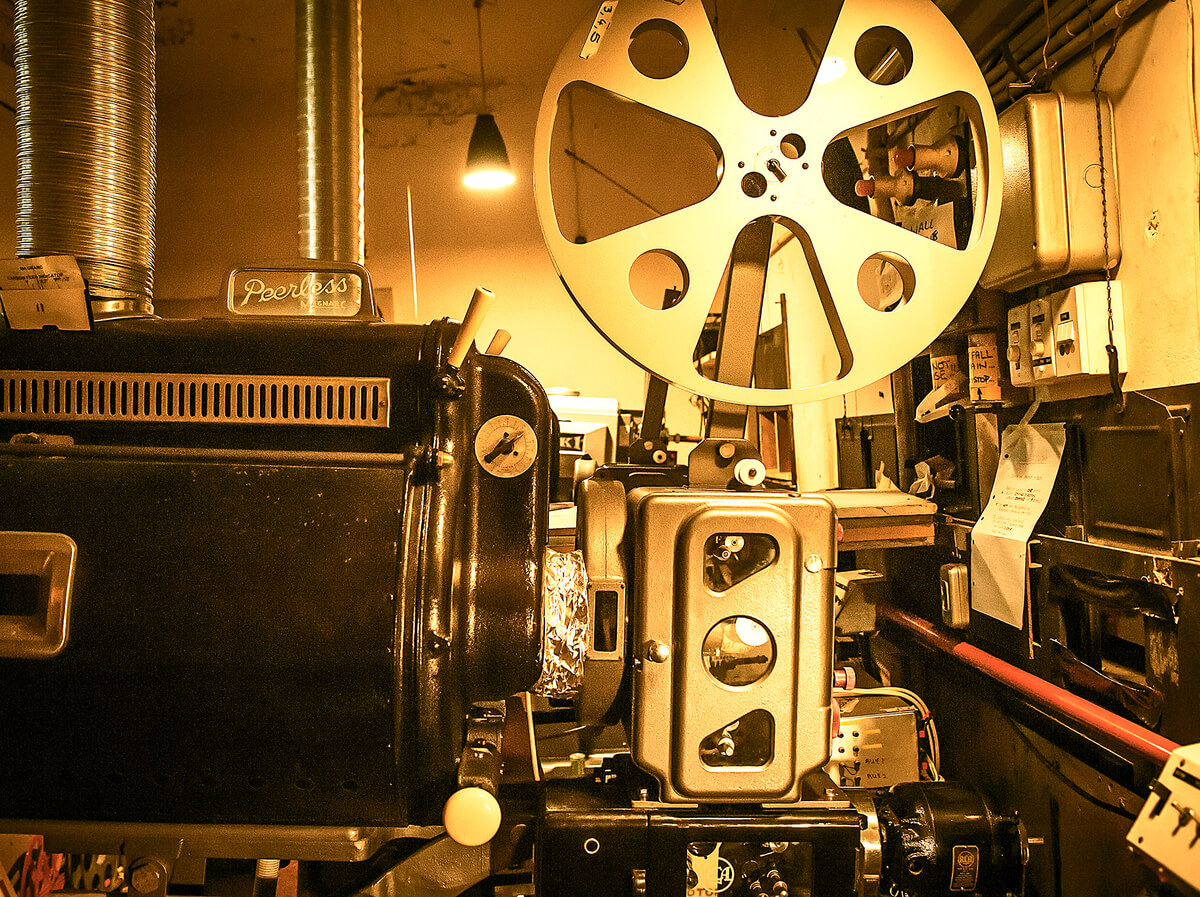

Opened in 1928, the Crystal Palace Theatre’s first movie screening — accompanied by a full orchestra and a celebratory light show — managed to short the local power station. Soon after, the orchestra pit was closed up, as it became the first suburban theatre to screen movies with sound, using the Western Electric Universal system, projected across the 765 seats by two very large wooden horns (now gathering dust behind the stage).

Underneath the theatre’s sloping floor was a large ballroom, a place made seductive in the 30s and 40s by the irrepressible Maori-Lebanese crooner Epi Shalfoon and his Melody Boys, who would spin a web of romance and good times with their dance-hall favourites.

They performed there every Saturday night for 19 years, until Shalfoon collapsed while dancing cheek-to-cheek across the kauri floor with his daughter Reo, and died.

Opened in 1928, the Crystal Palace Theatre’s first movie screening accompanied by a full orchestra and a celebratory light show managed to short the local power station.

The ballroom didn’t have a bar, but patrons found ways to make their Saturday nights slightly more hedonistic, with special coffees and secretly mixed “orange drink”.

“You used to be able to smoke in the ballroom,” says Taylor MacGregor. “And I’ve spoken to one guy who said when you stood at the top of that stairwell [leading down to the ballroom], there would be this red glowing light and all this smoke floating up from down below, as if you were staring into the pits of hell.”

MacGregor is one half of an outfit known as Monster Valley. The other half is Karl Sheridan. The pair took over managing the Crystal Palace at the start of this year in a custodial sort of arrangement, hoping to help keep the place alive.

They got involved after working on a short documentary about the Crystal Palace with a friend, director Robin Gee. “Through the process, learning more about it, and connecting with people who had memories of coming to the ballroom and meeting their spouse on the dance floor, or coming to films, we realised it’s been a really memorable place for a lot of people,” says MacGregor. “People are kind of attached to it, and have a lot of love for it. And in the end we decided we wanted to try and bring it back to life a bit.”

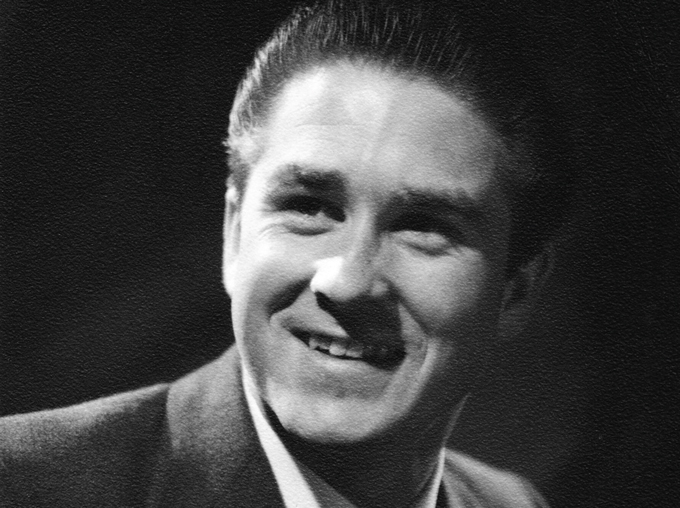

Along the way, MacGregor discovered it was his late uncle, Phil Warren, who reinvigorated the theatre in 1958, five years after Shalfoon’s death. Warren later became a well-known concert promoter, then deputy mayor of Auckland.

After telling his family about the documentary over dinner one night, MacGregor discovered his parents and aunts and uncles used to work at the Crystal Palace.

“They’d be taking tickets, coats, running money and so on. It turned out my uncle Phil restarted the ballroom downstairs when he was 19. So there’s a bit of blood, a bit of family history in it for me, too.”

Warren brought Merv Thomas and His Dixielanders to the Crystal Palace, making them the resident band, and slowly introduced jazz and also more theatrical stunt-like elements, along with coloured lights and mirror balls to the performances. He notably tried to turn it into a cabaret and bar in the 60s.

“We found all this documentation from when he tried to apply for a liquor licence, I think because it was something like the first suburban liquor licence application,” says MacGregor. “There were minutes from local board meetings and so on, and they were fascinating, with people alleging there would be orgies in the street. There were some very scared people who really had some amazing ideas about what would happen if they were allowed to serve alcohol here.”

The fact Warren was denied a liquor licence became the catalyst for a series of events that led to where the Crystal Palace is today. Though no one seems absolutely clear what happened between the late 60s and early 70s, we might hazard a guess that in accordance with changing times, the idea of a ballroom went out of fashion, and as television snared public attention, cinema-going declined. The Crystal Palace wasn’t the highly profitable enterprise it had once been.

Mercifully, no one tried to bowl the place over, and in 1977, the Chhiba family took ownership. They still own it today.

Raman Chhiba was a member of the fundraising committee for the Auckland Indian Association when he first came across the building, his daughter Rashmi says. “They were looking for another venue, because they’d outgrown the one in Victoria St, and the Crystal Palace was one place they were looking at. Then I think the Indian Association backed out or decided on somewhere else, and dad ended up saying, ‘Well, if you’re not going to do it, I will.’ And he ended up buying it.”

The family have fond memories of those early days, screening mainstream movies after their first release, and catering to the Indian community with Bollywood films.

“We were all quite young at the time, but like any Indian family business, we were roped in to help out, and so we’d take our school books along to do our homework after school, and we’d help out with the ticket sales or be behind the lolly bar and so on.”

As word spread the theatre was running as a cinema once more, it became a home for special events such as surfing movie festivals and midnight-to-dawn screenings. Film buffs were drawn in by the 35mm projector, one of the few left in New Zealand, and still used today.

“There’s a few other old film projectors in there — my brother Kiran would collect them from people or theatres who were getting rid of their old projectors,” says Rashmi. “Kiran was really the one who looked after the theatre for the family, who was most involved. He kept all the posters, and he loved watching the movies.” Later, the theatre also became known for “interactive” monthly screenings of The Room, a woeful 2003 American film that gained cult status thanks to its bizarre plot and unintentional humour. Audience members dressed up as their favourite characters, yelled insults and threw plastic spoons in reference to an odd framed photo of a spoon in the film.

“That was the first time I ever came to the Crystal Palace,” MacGregor recalls. “I came along to a Room screening, and that was quite an experience. All the throwing spoons and yelling at the screen, watching Ray [Chhiba] get the leaf blower out and blow all the spoons down the aisle.”

While use of the theatre tailed off over the years — today, films are screened only sporadically — the ballroom below has become a buzzing creative hive over the past two decades.

“I’m not sure how my father met Bill exactly, but I think he’d heard about Bill’s studio in Symonds St and got in touch after the previous tenants moved out. I think dad liked having musicians in there. He had trained as a classical musician, he played a lot of different Indian instruments, and he sang, and he would sometimes perform at fundraising events and so on. He taught the sitar to a few people.”

Though he had little to do with The Lab on a day-to-day basis, Raman Chhiba’s empathy towards fellow musicians, and his initial inkling the ballroom might make a reasonable recording studio, gave rise to something of a musical hotbed, which has continued to grow and flourish since his passing.

The community that has sprung up around The Lab is due to both Lattimer and engineer and producer Olly Harmer, who arrived from Christchurch in 2001 as a casual engineer. He became The Lab’s house engineer in 2003, and has pretty much run the place ever since.

Harmer has managed to create a highly respected studio filled with top-notch gear which remains affordable to a wide range of musicians. Along the way, he has won multiple New Zealand Music Awards, including Tuis for Best Engineer on Passive Me, Aggressive You by The Naked and Famous, and Drylands by Mel Parsons.

“There would be this red glowing light and smoke floating up from below, as if you were staring into the pits of hell.”

Welcoming is the perfect word to describe The Lab — there’s nothing precious or exclusive about it, and there’s an air of productive casualness about the place. Aside from the main studio and control room, helmed by Harmer, there are five studios, which are home to artists and producers Jol Mulholland, Tom Healy, Jeremy Toy, Alistair Deverick and Matthias Jordan.

The communal atmosphere wasn’t something Harmer set out to create, but it gives The Lab a unique quality among Auckland music studios. “It was something I kind of drifted into, really,” he says. “Different musicians over the years had come in and asked to use some part of the space for rehearsals or what have you. Matt [Harvey] from Concord Dawn and Dylan Wood were the first, I think, and then Paul Matthews was the one who turned the mezzanine into a room. Then Elemeno P wanted to create a sort of studio where they could do things themselves, and then Deja Voodoo did their third album in that back space as well. It was about the time when ProTools and things started to become mainstream, in the mid-2000s, and people were getting into DIY set-ups.”

Artists have come and gone through the years, though the current line-up is now quite stable, with both Mulholland and Healy busy producing albums for everyone from Anika Moa to Clap Clap Riot. The list of artists who have recorded at The Lab in recent years reads like a roster of some of New Zealand’s most progressive talent: Andrew Keoghan; Bespin; Delaney Davidson; Dictaphone Blues; Carnivorous Plant Society; Dimmer; Die Die Die; Don McGlashan; Hopetoun Brown; Lawrence Arabia; Maisey Rika; PNC; The Bads; The Checks; Rob Ruha; Tiny Ruins; She’s So Rad.

If that kind of list doesn’t shout “rare and important asset for our artistic community” at you, then nothing will. So often musicians, artists, innovators and creators will find a space or a building that’s a little worse for wear and make it their haven, turning it into an inspiring, lively community asset. But that attracts more people to the area, which becomes prime real estate, and those same creative people often find themselves priced out of their haven and shuffled off.

The brilliant thing about the Crystal Palace is that hasn’t happened. “The whole situation is incredibly lucky, really, having a heritage building owned by people who aren’t fixated on making as much money out of it as they can,” says Harmer. “It’s not a situation you’d often find. The fact they’re not charging us huge amounts of rent is very gracious, and I’m so grateful for that. The fact that this place can run on a shoestring budget means that it remains affordable for musicians, so hopefully we can carry on a while longer.”

The Lab’s existence has also been key to artists rediscovering the theatre upstairs. It was Hollie Fullbrook who really got the ball rolling with her show in 2014, and the idea to perform there came up while she was recording with Tom Healy downstairs.

“One day, an ad was being filmed inside the theatre, and so the front door was open, and I was walking past to go down to The Lab. I poked my head in, and that was the first time I’d ever seen inside. When I saw it, I just went, ‘Holy shit!’ I had no idea how beautiful and how incredible it was. And that was when I actually started wondering if it was possible.”

Healy mustered his diplomacy skills and approached the often-shy Kiran to ask if the family would consider opening the theatre for a live music event.

“We were all surprised when he said, ‘Yeah, yeah I’ll let you do that,’” Fullbrook says.

There was a lot of work involved in getting the venue ready for a live gig — setting up lights and sound gear, decorations, organising a bar, ticketing, eftpos machines, cleaning — but Fullbrook and her band, along with a group of friends, made it happen. Because Kiran hadn’t charged them much for venue hire, they were able to make it a surprisingly profitable gig while still keeping ticket prices low.

“We didn’t realise it at the time but that show was incredibly important for us financially,” says Fullbrook. “We were about to go on a lengthy world tour, and suddenly we had to book all these flights and pay all these expenses, and if we hadn’t done that show, we would’ve been screwed financially.

“Some of the big venues in Auckland, the amount is crazy, and it means you have to put the ticket price up so high. [We] always want our shows to be accessible, which was something we could achieve at the Crystal Palace.”

It was a special event for the audience, too — a night out which felt full of anticipation and elation, the sense of a joyous shared experience. The grand proscenium arch, the perfectly sloping wooden floor and even the slightly rickety seats added to the air of occasion.

“Even in a slightly decrepit state, it’s still really beautiful, particularly in respect of representing a time gone by,” says Fullbrook. “There was this feeling that it was this special place we wanted to bring some life to again. A sense of wanting to do the building justice, I guess.”

Fullbrook is grateful to the Chhiba family for agreeing to her gig to begin with — “It would’ve been very easy for them to say no” — and for continuing to help with preparations after Kiran’s unexpected death three weeks before the show.

“There was this feeling that it was this special place we wanted to bring some life to again. A sense of wanting to do the building justice.”

“It was really, really sad, because he’d been great to us and he was such a sweet person. Obviously his family were in a state of grief and yet they said the show will go on. It was quite emotional. I think Kiran would’ve loved to see the space in use, and see all these people in awe of it.”

While no one involved wants to see the theatre overrun, or the building used in an unsustainable way (gently and kindly are two words that come up frequently), with Monster Valley now taking the reins, things are certainly looking a little more lively. They’re hoping to fire up that 35mm film projector and are talking with the national film archive about running a series of events. In October, rising stars Leisure are performing, and Don McGlashan and Shayne Carter will take the stage together as part of their national tour.

“The great thing about this place,” says MacGregor, “is that everyone who comes here, because of the size and the special kind of quality it has as a venue, the artists want to do more. They’ve got to do something to try and make it bigger and more of an event. It pushes people to create a great show, and with diminishing venues in Auckland, for people like me and Karl who love music, we feel like we should make the most of this amazing venue and the opportunity it offers.”

It’s heartening a building that once reverberated with music is still here, and humming again, nearly a century on.

This article originally appeared in the October issue of Metro