Nov 17, 2015 etc

Author, poet and playwright Courtney Sina Meredith has a vision of “Urbanesia”.

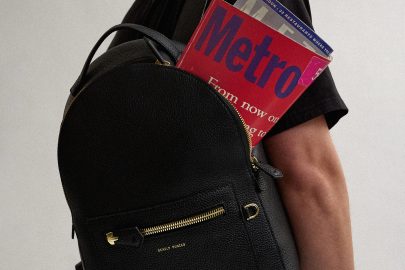

This article was first published in the November issue of Metro. Photos: Jane Ussher.

Friday evening: the city takes a breath between work and weekend. In the corner-store HQ of Beatnik Publishing, Eden Terrace, a small crowd gathers to hear Courtney Sina Meredith read from her work in progress: a collection of short stories, Tail of the Taniwha.

Meredith, 29, is of Samoan, Irish and Mangaian (Cook Island Maori) descent. Known best for her poetry, she has a book of poems, Brown Girls in Bright Red Lipstick, and is an accomplished performance poet. She’s also written a play, Rushing Dolls, which is included in two anthologies, and was workshopped by Silo Theatre in 2015.

With a Creative New Zealand grant for Taniwha — her first serious foray into short stories — she’s feeling some pressure to prove herself. This evening, her mum and manager, arts publicist Kim Meredith Melhuish, is MCing; her stepfather (whom she calls Dad), jazz musician Kingsley Melhuish, opens with a live solo performance.

The extracts she reads are densely lyrical. Her words hustle and sing and scrap; her delivery is electrifying. A loved-up character allows himself a romantic delusion: “I’ll be safe to swim out towards her, just a little, and be the dolphin by the cruise ship that brings joy.” Another character runs late, “making it to the boardroom in a detailed heap”.

During a music break, Meredith tells me: “I love these, they’re my babies. If I read them I’d think, this is what I want to write. If a friend wrote them, I’d be super-jelly.”

The next story is about a young Samoan Aucklander who visits the Tate gallery in London and is disturbed by a Matisse portrait of an unnamed nude brown woman. It’s told through an internal dialogue she has with Nafanua, the Samoan goddess of war. Later, she realises she’s being observed as if she’s up on a wall. “They put us up on the walls because we are works of art. But they’ve got it the wrong way round: they’re not looking at us.”

Meredith looks up. “I’ve felt like that a lot in my life, that I’m being observed: ‘Look, she’s so articulate; what will her next move be?’ ‘Oh, she read books when she was a child; quick, take a picture!’”

Two things about Meredith are obvious tonight. One, she’s not flying solo — her career is a family affair. Two, she has this crackling quality, a blend of effusive confidence, magnetism and spiky defiance.

“When my book comes out,” she tells me later, “I imagine there’ll be a lot of people who’ll say it’s too poetic, that parts are really indulgent because you can tell this is something the writer is really passionate about. It’s celebrated if you want to be an artist or musician to follow your heart, but with writing, people are saying, ‘Put your heart into a jar beside your laptop until you’re finished.’ I don’t want to spend four pages on slowly rowing a boat. If you want distant, distilled prose, you can go to a lot of other New Zealand writers.”

Courtney Meredith and Ole Maiava perform at the Bibliothekszentrum in 2012.

A micro-pause. “I also think there are privileged white males who’ve always been written for, and they can’t understand they’re not the ones I’m writing for. People say the problem about writing in your twenties is it’s so me-me-me. I just think you can’t handle a world that wasn’t designed for you. That criticism’s something I’ll have to get used to because I don’t see my voice changing, I see it strengthening. And I think there are people hungry for this kind of voice.”

Don’t trust a Samoan girl

she’ll eat your heart while you sleep

until you are silt in the corners of pink state houses

— “Don’t Trust a Samoan Girl”

Her answers to my questions fluctuate between warm, free-flowing intimacies, a marketer’s peppy, on-message self-promotion, and the heartfelt polemic of someone who feels the weight of representation.

She lives at her mother and Melhuish’s home in Newton with their sons Cyrus, 12, and Pele, 10, and the family dog, a pampered greyhound named Miles. She works part-time as partnerships manager — a role created for her — at the Manukau Institute of Technology’s arts faculty. She’s well connected, after several years working for the Auckland Council in arts adviser roles. And she’s ambitious for the faculty: in August, she arranged for two German artists to come and paint “EARTH” in giant red letters on the roof as part of a five-continent project (see remotewords.net).

Poet Robert Sullivan heads the faculty’s creative writing school, housed in what was once the Bluebird chips factory in Otara, with a teaching staff that includes Eleanor Catton, Anne Kennedy, Catherine Chidgey and Tusiata Avia. Sullivan, who wrote the introduction to Brown Girls, met Meredith on the performance-poetry circuit. “She’s got this calm energy that she shares when she’s on the stage,” he says. “It’s kind of volcanic, but without the eruption.”

The pair held writing workshops and poetry performances to spark interest in the creative writing school before it opened. Meredith has lectured there and informally mentors young writers. Sullivan recalls her sitting down with some nervous poets before an event and eliciting the best performance he’d seen from them. “It wasn’t what she said, it was the way she said it. She calmed us all down, she took all the risk from it she could, just telling them to be themselves … She’s a generous spirit. When she’s there, she’s really there, whether with beginning or established artists.” Her successes, he believes, flow from the strength of her family. “That feeds the generosity that works through everything she does, including the poetry.”

It isn’t like an Island nipple nup

no breezing trees and caramel sand

no coconut truths spilling over woven fans

no plans of making love to the land.

— “No Motorbikes, No Golf”

Meredith’s childhood was marked by closeness to her mother, and by loss. Kim had Courtney at 20. For 15 years, until Kim got together with Melhuish, it was the two of them against the world. Meredith’s father, a sailor, didn’t stick around, though he’d take her to a movie when he was in town, and his mother, who lived in Herne Bay, helped Kim with childcare. As an adult, Meredith visited her dad’s family in Rarotonga.

“Mum’s never said a bad word against him, always encouraged me to have a relationship with him… She has so much integrity,” Meredith says. “I don’t think I’ll ever stop being angry with him. He was around, but he did the bare minimum.” Her pain is unmistakable but, somewhat jarringly, she says this brightly. (A line from one of her short stories is: “My dad is a seaman; he fucks off for a living.”)

Kim brought baby Courtney home to her parents’ small state house on Taniwha St, Glen Innes. Kim’s brother, his wife and their baby, Danielle (Dani), and Kim’s sister and another brother were also living there. Meredith remembers a happy, loving childhood. The title of her short-story collection recalls hours spent sitting on the front steps imagining that “the tail of the taniwha was right there in front of me, silver and gold scaled under the front lawn. I dreamed about it thrashing around, waiting for me to grab hold and climb its body… I figured the head was in New York, or Paris, or London.”

At six, she experienced the loss of her grandma, Rita, who’d quit her factory job to look after Meredith and Dani so their parents could work (Kim as a journalist). “It was the worst time of my life. I had nightmares for a long time, I could see things moving through the air, I heard voices, I was convinced that Grandma wasn’t dead and that we had to go and let her out of her coffin.”

The second chapter of her childhood was set in the bohemia of 1990s Ponsonby. Kim did a story on Ponsonby Primary School and decided she wanted Courtney to go there, so mother and daughter went flatting in Ponsonby. They lived with many creatives over the years, recalls Meredith: “Most of the bro’ Town guys, Shortland Street actors, Pacific artists. Things got intense at times. It was fun, but crazy! It was never a question of am I going to be an artist, but what kind?”

She started writing poems around age five, inspired by her mum writing a poem after school one day. “Mum’s poetry was the first thing I loved as a little kid. You live a moment, you take all the glitter or residue from that moment, you put it on the page and you can revisit it any time. It’s like time travel.”

When Meredith was seven, Kim started university. She took her daughter along to lectures in the school holidays, and Meredith would scrawl stories and verses, or feedback that she delivered to the lecturers at the end of class.

When Melhuish joined the family, Meredith was at Western Springs College and doing a lot of songwriting. “Mum and Dad really grounded me,” she says. “They were also hard on me, always looking for improvement. I won best lyricist and vocalist at Smokefree Rockquest. Everyone else’s parents were like, ‘You did great, you were wonderful!’ My parents were like, ‘Okay, but your phrasing was out on that.’”

Meredith brought her first girlfriend home at age 12. “I was dating girls and boys in the sixth, seventh form. I had teachers who were into the Queer movement and so supportive.”

“Mum and Dad really grounded me. They were also hard on me, always looking for improvement.”

Early on, her mother recognised that Meredith’s blend of charm, earnest intensity and grit was dynamite. “We often say if she wasn’t doing this she’d be a cult leader,” says Kim. “Courtney from a very young age was driven and tenacious and focused on what she wanted. When we saw how persuasive she was and she got a bit older and started to ham it up, I took her aside and said, ‘You need to use your powers for good, to better yourself and others.’”

I miss being back at Law

only because

you used to kiss me in the toilets at Rakinos

and say I aimed sky-high sitting on roots in Albert

park

— “Jam Sandwich on the Lawn”

After high school, Meredith had plans to own a bar with her cousin Dani, whom she calls her “spiritual Siamese twin”. Her mother intervened, enrolling her in the New Start programme at Auckland University, and her high grades prompted the law school to invite her to an evening for prospective Pasifika students. She started a law and arts conjoint degree, but law was never her calling and she dropped it in her third year. Her mother was worried she’d become a quitter. “I had to convince her that I knew what I was doing, and I promised to throw myself into my arts degree, looking to become a writer,” Meredith says.

“I totally fell in love with the Victorian poets. Elizabeth Barrett Browning came into my life at just the right moment, and between her and Christina Rossetti and Aphra Behn, I started to understand the yearning that I felt to speak up, to be heard, to have a voice. We were surrounded by an ideology of brown women as submissive, quiet, conservative and limited… I started writing lots about family, sexuality, kindredness, parties and gods — I wanted my words to jump off the page and challenge the reader, or the listener.”

She got into the Auckland slam poetry scene (competitive performance poetry). Meanwhile, some of her poems were published in an anthology of Pacific and Maori writing. Renowned choreographer and dancer Lemi Ponifasio, a family friend, saw her perform at the anthology’s launch, and promised to try to piece together a writer’s residency for her in Europe.

Sure enough, he spoke to the head of the Internationales Literaturfestival Berlin (ILB), who invited Meredith to the 2011 festival, even though she hadn’t yet published a book. Ponifasio hooked her up with a six-week residency at a hotel, and invited her to write a poem in response to a show his dance group Mau was premiering while she was there. She performed it before an audience of 1000, including the German president.

Melhuish spent the first two weeks with her; her mum joined her for the final two. The couple had secretly hoped for a small-fish-big-pond experience. “But it was terrible,” says Kim. “Everybody kept telling her how amazing it was. I thought, she’s not going to be able to come inside because her head won’t fit through the door!”

In 2012, she was back in Germany for Brown Girls’ launch at the Frankfurt Book Fair. That same year, she toured in the Indonesian International Poetry Festival, participated at events in London’s Cultural Olympiad and addressed members of the House of Lords. She recalls phoning her mother: “I’ve been invited to the House of Lords. They acknowledge me as a global voice. There are world leaders who want to meet me!”

These experiences were surely thrilling and formative, and no doubt she earned her place. But the significance she attaches here suggests a blind spot about the nature of the literary junket circuit. Perhaps this comes from her hunger to be affirmed as extraordinary and extraordinarily influential — not simply to feed her ego (though, hell, who doesn’t want to be told they’re amazing?) but to be taken seriously as a voice for brown women everywhere.

I want to be an activist but my country is sleeping

I thought I’d be an actress but my ethnicity’s hungry

me versus the monkeys on how to beat the junkies

I’m not a ‘luck’ advocate but I’m sick of fate

or — faith in the new world with its old name.

I’m a girl in a girl in a girl in a girl

I’m a Rushing Doll.

— From the play Rushing Dolls

Central to Meredith’s play, Rushing Dolls, is her vision of Urbanesia: cosmopolitan Pasifika worldwide. In her character Cleopatra’s words: “My unique Pacific perspective, it’s intrinsic to who I am, which is ambitious, educated, deftly passionate, urbanesian, a new breed.”

Meredith was 24 when she wrote the play, which follows Cleo and Sialei, two cousins in their 20s, modelled on her and her cousin Dani. It’s intellectual, sexy, sweary and urban. The cousins frequent galleries, parties, restaurants and strip clubs, and regularly burst into verse. Cleo delivers a go-forth-and-conquer speech to school leavers in South Auckland: “Fearless and babyless. No jail time, no handouts. And no fucking excuses.”

Writer-director Toa Fraser (No. 2) helped develop Rushing Dolls, which has won three awards, but hasn’t yet been staged, though it was one of three works by emerging women playwrights chosen for workshopping by Silo Theatre this year.

Meredith bristles at early criticisms: too highbrow, unbelievable. “People say to me, ‘Women like this don’t exist,’ and I say, ‘I don’t think it’s the place of art to represent just what exists now.’ I also disagree: I know lots of women like this. People have been a lot harder on those characters than they’ve been on other experimental works.”

She says the play “directly opposes” a lineage of Pacific literature that’s “very male-dominated, happy for women to be support acts”. Established Pacific female playwrights “tend to be from a generation above me and concerned with a longing for the Islands, for traditional identity, a sense of being stuck between two worlds. And then to have these two young women who are comfortable with where they are and embrace the city and want to have sex and travel…!”

Here’s that blindspot again: poets such as Tusiata Avia and Selina Tusitala Marsh have also written about sexy, powerful, urban brown women. The sticking point for Meredith seems to be two-fold: a sense of belonging to a different generation and the theme of afakasi identity.

“I have problems with that word ‘half-caste’,” she says. “I like to look at people as unrepeatable beams of light; I’m aways stunned and frightened by people trying to fraction themselves. A lot of half-caste writers have said to me, ‘You’re lucky because your mum is brown.’ They’ve had white mums and that makes them feel a step back from their culture. But it’s a tough one, because my father was never around — I say, ‘Isn’t it just cool that you had both parents around? It doesn’t matter if they’re white or brown.’”

Meredith hates cultural gatekeeping. “The idea you have to perform being someone all the time is so exhausting and it holds us back from being change agents, masters of our own destiny.

“You get so caught up in that web of trying to prove you’re authentic. We’re so hard on each other. We get so enmeshed in who’s giving most money to the church, how many pigs did you have at your wedding? How are we addressing poverty, drug abuse? Is there a dance that can address rheumatic fever?

“It breaks my heart that we have so many Pasifika youth suicides now, and research suggests that 80 per cent of them are based on not feeling connected. I want so much for people to feel it is their birthright that they are who they are, that culture isn’t about regulating something that’s been before, it’s about looking after everybody.”

Crucially, she wants to create work “inspired by, motivated by, and tailor-made for brown women the world over”, without that work being reduced to identity politics. “If I write about my childhood and who I am, it is considered identity [literature], but if you have a white male writing about his childhood, then that’s New Zealand literature.”

At least a few privileged white male writers rate Meredith, including Lloyd Jones, a manuscript adviser for Tail of the Taniwha. “So much of the writing in New Zealand and elsewhere has a sameness,” he tells me. “At times, I feel that all it seeks for itself is to be described as ‘well written’. Courtney’s writing is summoned from a different place — not exclusively literature, but from music… When she gets it right, that rawness lands on the page.”

Brown girls in bright red lipstick

have you seen them

with their nice white girlfriends

reading Pablo Neruda

on fire the crotch of suburbia”

— Brown Girls in Bright Red Lipstick

At times, I sense a great effort beneath Meredith’s upbeat, on-message, enthusiasm (that beautiful crackle). She tries so hard; wants to be taken seriously, to reach people, so badly. And it feels like she uses this happy spin partly to offset her personal suffering. It’s her mother who first mentions Meredith’s severe endometritis, a painful, chronic condition for which she had surgery at 23.

She’s also suffered in love. In her mid-20s, she met and fell hard for a woman who worked as an art gallery curator. They got engaged. Meredith followed her to Rome, only for her fiancée to dump her on her second day there. “She said that things felt different but that she couldn’t explain why, and what followed were months of grieving and starving in London, foolishly hoping that things might miraculously work out.”

Her family urged her to come home, but she hung in for a year. The blow excavated another buried grief, for her half-brother born after Cyrus, named Kingsley, who lived only an hour.

When Meredith emails me with the details of her broken engagement, I can’t believe her frankness: I mention this to her mum, who surprises me again by saying Meredith showed her the email first.

“A lot of the things that are her strengths are also her weaknesses, vulnerabilities,” Kim replies thoughtfully. “She’d meet people and open herself up completely, straight away, and we said that’s just not sustainable. But having those deep connections are really important to her. She’s having to relearn how to be with people. Hers is a hard road because she has a lot of people who are drawn to her because of her art, but then there’s also Courtney the person. Who is just this really sweet girl.” ?