Feb 28, 2022 Books

In October, I was a part of a “gender” panel at the New Zealand Young Writers Festival. It was one of those panels where I went into it slightly uncertain about what the audience and I might get out of it. Is there anything left to say about gender? In hindsight, of course there is, and one moment from that panel that sticks with me is when co-panellist Kerry Lane described gender as “an ongoing conversation”. For me, all expressions of gender, sexuality, queerness and belonging can encompass the idea that these different expressions are part of an ongoing conversation with the self. It is a way of layering or unfurling the skin or of creating an opacity, where we can both reveal and conceal the parts we share about ourselves.

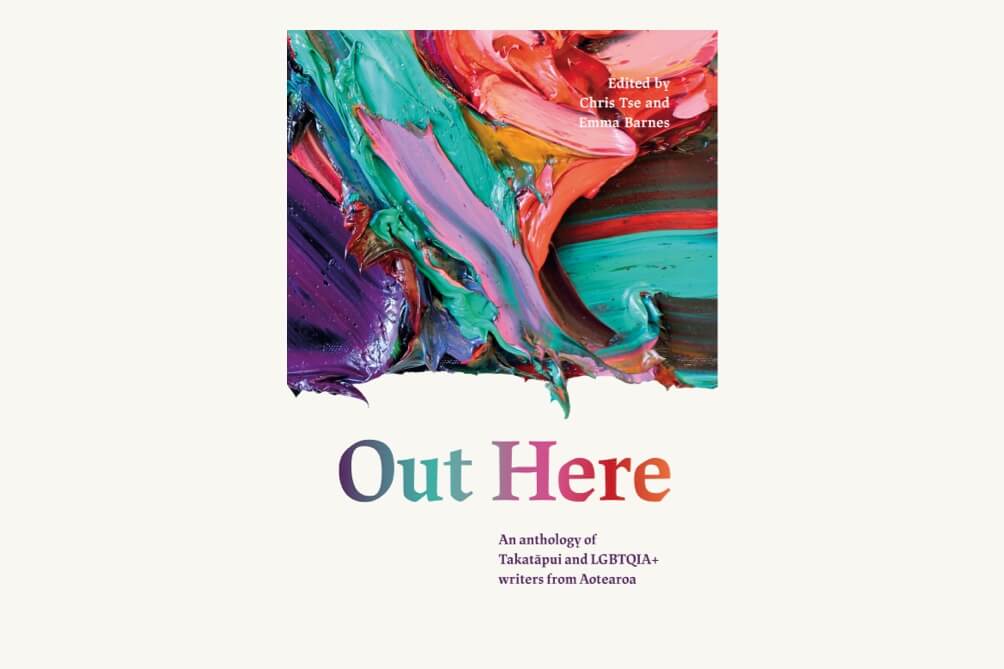

In the introduction of Out Here: An Anthology of Takatāpui and LGBTQIA+ Writers from Aotearoa, editors Chris Tse and Emma Barnes expand upon their hopes around what these kinds of conversations can lead to. In Out Here, we see the ways in which many LGBTQIA+ writers push beyond the expectations of what queer writing can be and in doing so illuminate queer writing within Aotearoa’s literary history. Out Here includes brilliant writing traversing age and career stage, from Witi Ihimaera and Renée to Hera Lindsay Bird and Ruby Solly. It includes poetry, short stories, essays, comics and more. The book’s cover is wrapped in a thick skin of vividly coloured paint taken from artist Jack Trolove’s The Thick skin of a Pronoun (2019), which serves as a reminder that the body can be constantly made and remade. There is no one tone that can shade the way we see the world, nor how we constitute our understanding of bodies, memories and desires.

Often, queer spaces are dominated by Western understandings of gender binaries and sexual practices that are wholly celebratory and uncritical. Many of these spaces fixate on certain bodies, usually the white, cis, male ideal. We often see this in “rainbow” participation by, say, banks sponsoring the Pride Parade, or police marching in it, or the Israeli government’s public relations campaign of LGBTQIA+ friendliness while simultaneously committing human rights abuses in Palestine. This kind of pink washing often excludes the many peoples who make up the LGBTQIA+ community, silencing any examination of the more painful parts of belonging. Throughout Out Here are many stories rejecting these narratives and providing an expansive space for sharing that often centres around the struggle to belong, rejection, shame, heartache and self-harm. A work that stands out is Sam Orchard’s “Pride and Belonging”, where a character asks:

‘How can we heal when we’re only allowed to celebrate?’

‘And how can we celebrate when we’re still being hurt and still hurting others’.

Many queer epistemologies account for sadness, longing or collective suffering brought on not simply by virtue of the difficulty in living your life on your own terms, but also in living under what Judith Butler describes as “rigid forms of gender and sexual identification, whether homosexual or heterosexual” which “spawn forms of melancholy.” Butler goes on to note that in order to work through this melancholy it’s useful to refuse these kinds of classifications and maintain a tactical optimism allowing you to be open to learning or unlearning. For instance, as a teenager I thought I was gay — probably the most optimistic option for a teenager at that time — before later realising, after much learning and reflection, that I was both queer and non-binary. This speaks to two parallel ideas: first, the Italian communist Antonio Gramsci’s idea of the pessimism of the intellect and optimism of will; and second, queer theorist Lauren Berlant’s ideas in her book Cruel Optimism. In Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, he describes optimism as a necessary part of political action, but one that must be kept in check by the intellect (that is, a sense of realism). Berlant’s idea of cruel optimism is based around an assertion that we all have attachments to objects or desires or dreams that are inherently optimistic, but don’t always work out or satisfy us. In these cases optimism is cruel.

Out Here

Yet not every form of optimism is cruel. Optimism often makes our life bearable. Many of the writers in Out Here speak to that cruelty and melancholy of optimism, but also how it can gently begin to heal wounds and open up vulnerabilities. In Jackson Nieuwland’s “I am a version of you from the future”, we see the tension between optimism and melancholy, which is punctuated by a nostalgic, but realistic comprehension of their past. Certain lines are painful to read, some have the gift of hindsight, while others fill you with hope and care.

It will be the worst year of your life…

Your best basket memory won’t be representing your country it will be playing with your friends… You’re doing so well I’m so proud of you…

Each stanza repeats the line “I am a version of you from the future” and in doing so recalls Nieuwland’s debut book of poetry, I am a human being, which won the Jessie Mackay Prize for a first book of poetry at the 2021 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. The repetition in “I am a version of you from the future”, not unlike that in I am a human being, reads like a chant oscillating between emotions, memory and a conversation with yourself. Nieuwland makes their wounds legible in order to embrace a tactical optimism, while not being bound to hierarchy.

I am a version of you from the future.

This is just the beginning

Across Indigenous communities, diverse genders and sexual practices weren’t necessarily seen as a deviation from the norm. Jessica Niurangi Mary Maclean confronts this in “Kāore e wehi tōku kiri ki te taraongaonga; my skin does not fear the nettle”, writing that “Diversity has always existed and therefore existed i ngā wā o mua, in the olden days”. Often the spectrum of Indigenous sexualities does not and cannot fit neatly within Western queer narratives. It is not that they are invisible or untranslatable, but rather have been distorted through the process of colonisation. This was a conscious drive on the part of colonial forces. Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson notes that the imposition of the Western gender binary — male and female — acted as a mechanism to force Indigenous peoples and their identities into manageable norms. Maclean gently probes the potential for fluidity within tikanga Māori, particularly within the pōwhiri process and the gender roles it sets out. They also discuss the interrelationship of all living things to one another and the overarching principle of balance or mana taurite within te ao Māori.

One of the interesting details Maclean outlines is gender neutrality in reo Māori, explaining that there is no “he/she” or “his/hers” in the Māori language. Instead the gender-neutral “ia” and “tāna/tōna” act as personal pronouns. This use of gender-neutral language — “ia” refers to “them”, so a collective referral — illuminates how Māori understand the world in terms of whakapapa, not individual gender. Maclean uses this example to advocate for a new collectivity that includes all of takatāpui kin, through the act of manaakitanga: “discussions mustn’t happen without takatāpui being central to these processes, and we must uphold manaakitanga at all times”. Maclean reminds us that in order to envision and build strong Indigenous nations based around the celebration of diversity, a fluidity around gender, individual self-determination and the Indigenous philosophies that allowed tūpuna to do that, then we must hold space for everyone.

Pelenakeke Brown’s “A Travelling Practice” is a provocation in which we see a multidisciplinary way to imagine the body moving through space and time. Brown thinks through the keyboard as a space that has pre-existing relationships, which are in many ways a universal language, but reinscribes it as a space that also reflects the propelling forward through time tā (time) and vā (space). Brown identifies certain keys as being not dissimilar to Samoan tatau, especially malu, which is traditionally worn by women.

The continual striking of tā in my movements in this liminal vā the continual pressing of return (or is it enter?)

“A Travelling Practice” echoes Leanne Betasamosake Simpson who describes Indigenous bodies as existing in relation to “complex, nonlinear constructions of time, space and place that are continually rebirthed through… the recognition of obligations and responsibilities within a nest of diversity, freedom, consent, noninterference and a generated, proportional, emergent reciprocity”.

Editors Barnes and Tse have successfully collected together a web of beautiful and difficult stories, experiences and voices that make the book pivotal in the history of queer writing. Both should feel incredibly proud for filling an obvious gap and making these stories visible in all their nuance and complication. The strength of this book is in its collectivity. I am reminded of the words of Black abolitionist Angela Davis, who wrote that, “It is in collectivities that we find reservoirs of hope and optimism.”