Mar 9, 2023 Books

“A bad day at the bus-stop can sometimes feel like a symphony of bullshit,” Te Hoia thinks at the beginning of How To Loiter in a Turf War, the debut novel by multi-hyphenate artist Coco Solid, aka Jessica Hansell (Ngāpuhi/Sāmoa/Germany). Our narrator’s bus still hasn’t come, she is “morbidly late” for her class at uni, and there’s something about the bottomlessness of waiting for a bus that may or may not show that makes gentrification’s slow creep into her neighbourhood feel more like an inundation.

Writing his poem ‘Ode to Auckland’ in 1972, James K Baxter could find no opening line more appropriate than, “Auckland, you great arsehole”, protesting that this town was “made like coffins” and that the sounds of mundane urban life do their best to drown “the song of Tangaroa on a thousand beaches / The sound of the wind among the green volcanoes”. Fifty years later, by Solid’s account, Auckland remains a great, probably even bigger arsehole — no matter how many times or how enthusiastically we might say the word ‘development’.

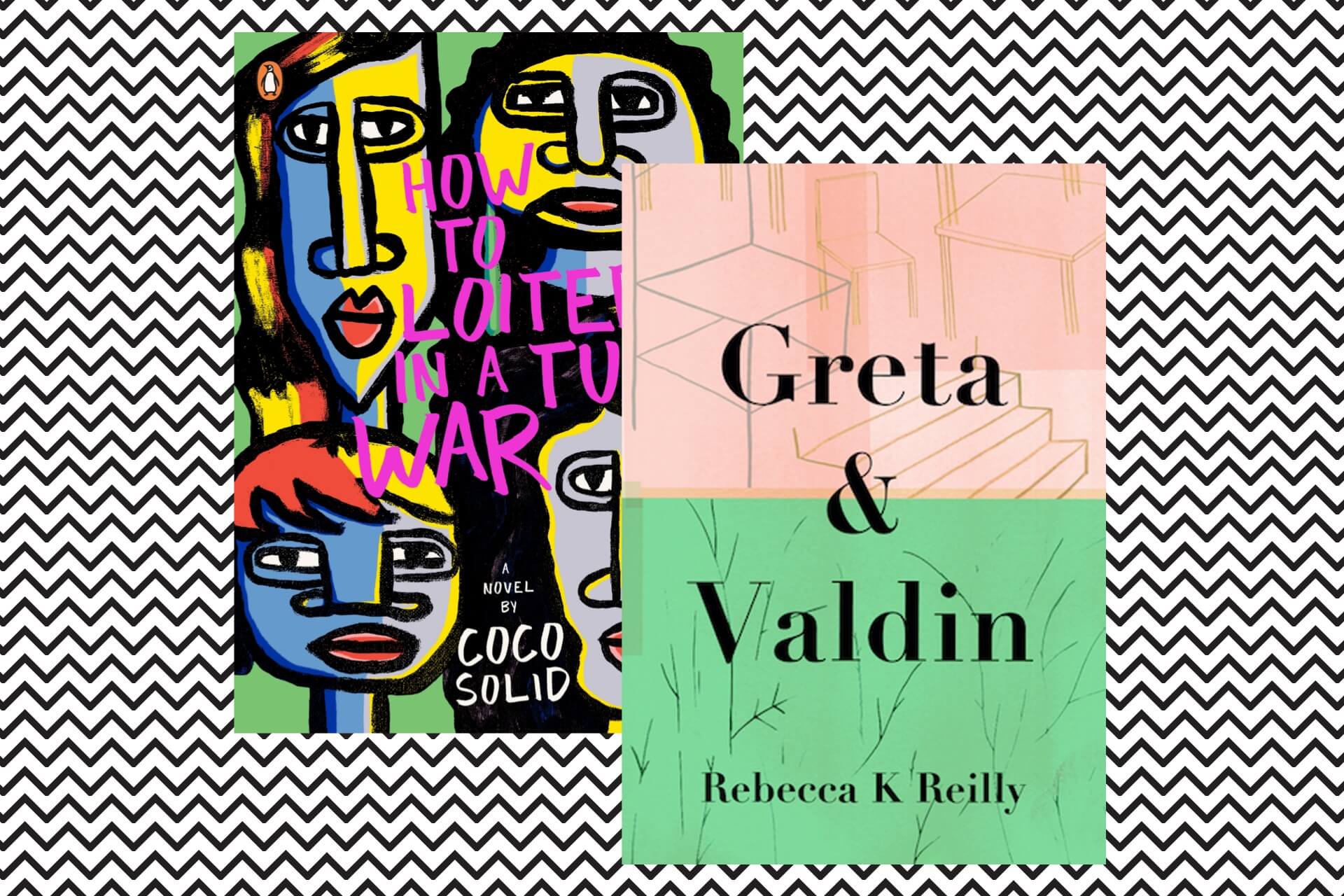

Arseholiness, however, makes a fertile setting for contemporary fiction, from which the best and worst aspects of Aotearoa emerge. Turf War affirms as much, as did Greta & Valdin, the debut novel by Rebecca K Reilly (Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Wai), released in 2021. The city wedges itself through both novels like dandelions through the pavement: in Turf War as the foe of Te Hoia and her two best friends, Q and Rosina; in Greta & Valdin as the sharply observed backdrop to the meandering and mildly painful love stories of two siblings and their extended Māori-Russian-Catalonian family, often as suddenly and cruelly and confoundingly cold as their partners.

“The novel: history sends the reader away and brings him back again”, wrote literary critic Elizabeth Hardwick in the New York Review of Books in 1968, yet these two novels often send us only as far as the end of the street. Like Reilly’s characters, I have used public transport to excuse myself from dates I no longer wanted to be on. Like Solid’s, I have spent half-lifetimes waiting for public transport when I actually do need to use it. Most of these two books I read during the weeks in October 2022 when the Western Line was disrupted by subsidence issues that turned my usual commute from Swanson to the CBD into a three-hour-long, deeply uninteresting odyssey.

Why should we want to read about the places in which we live? Some days, the ones where the bus doesn’t come or the bigot comes to power, just living in them feels like enough, and fictionalising these frustrations seems at best tedious and at worst masochistic. But reading Turf War and Greta & Valdin is neither of these things, even if they are attuned with frankness and intensity to the complexion, infrastructure and patterns of sociality that make up Tāmaki Makaurau (and that often make it insufferable).

Reilly wields adeptly the specificities of place to build a world furnished with familiar details: too many Glengarrys, the Farmers Santa, the smell of raspberry shisha on High St, gelato flavours at the ferry terminal shop and their impatient servers. In one passage, Greta flees home from the university campus in distress, offering a breathless but sharp image of the city as she descends through Albert Park:

I run down the stairwell, out the automatic doors, through the underpass, past the plaque dedicated to the Ghost of Vale, past the Michael Parekōwhai security guard statue, along the wall that may or may not have something to do with the Māori Land Wars, past the library, under the tree that smells like weed, through the muddy entrance to Albert Park, past the fountain where people want to take their graduation photos but it’s never good weather on graduation day, past the newly blooming daffodils and tulips, under the magnolia trees, over the huge knotted tree roots …

And so on “past the shoe shop where people sit in chairs camped out all night for Yeezys” and “the foun- tain where teenagers always hang out” and into her building. Greta hyperventilates the reliable chaos of the city, zooming in and out on its landmarks and minutiae like a malfunctioning camera. The glitchiness of this sensation — lurching between extreme dissociation and extreme presence — is made more palpable for the read- er who has walked this same route themselves, noticing these same things, if never quite so agitatedly. Reading about it, as the uni, the park and the streets take stark but fleeting shape as images, is to experience something not unlike the out-of-body experience that Greta herself is in the grip of.

Reilly cleverly mines the two degrees of claustrophobia that is living in Aotearoa for both comedy and empathy, knowing that her observations will land in the near vicinity of much of her readership, to the effect that, reading on the train, it felt plausible that Greta or Valdin or any of the book’s troupe of characters could be one of the other commuters with me in the carriage. The book has hills in all the right places, and each is offered up by its sharp-witted narrators as an in-joke to the reader who has also walked them. If it is playing on relatability, though, is not in the flat, gratuitous way that invites the reader to site themselves in the text and only that, but as an invitation to place its characters in a common and imperfect world with Auckland as its locus — which in Reilly’s story, as in our own, is a world of precarious employment, of unpredictable mental health, of complex families, identities, and unatoned colonial histories.

How To Loiter in a Turf War, too, crafts a detailed setting and social fabric around which its characters move — or refuse to when it tries to push them out. Sketchy bus timetables are just the latest way in which her city is letting Te Hoia down. Also on that list are the organic markets and their racist salespeople where the Chinese market gardeners and wedding dressmakers used to set up shop; yet another open home marketed as a “diamond in the rough”; and too many of her acquaint- ances appearing suddenly unhoused.

Solid conjures Tāmaki not only as a setting, but as an adversary, against which her characters, Te Hoia, Q and Rosina, are continually embattled. Each walk the characters take through their neighbourhood is a marking of territory, and all waiting is a kind of stake-out against the city’s corporate, bourgeois advance. During Te Hoia’s wait at the bus stop, nearby roadworks splutter out asphalt like “a remixed cannon clap”, announcing another wave of land seizure to her — this time under the banner of ‘urban revitalisation’ instead of the New Zealand Settlements Act. “The racket is the same,” Solid writes, “it just has a more attractive typeface.”

Séance-like, Solid’s prose teems with the remembered smells from beloved takeaway joints, the shadows of closed-down establishments, Land War battles, and with the voices of gossiping gods, poets, scholars, artists, families and shop-owners who have tended the turf before now. Like Patricia Grace’s Pōtiki, published in 1986, these endless, entwining chatterings establish the story at hand as the ‘now-time’ around which all time spirals. “This now-time,” Grace wrote, “simply reaches out in any direction towards the outer circles, these outer circles being named ‘past’ and ‘future’ only for our convenience […] So the ‘now’ is a giving and a receiving between the inner and the outer reaches.” The illustrations, the poetry, the excerpts from Te Hoia’s uni readings that Solid weaves through her narrative are all tethers between her characters and a larger social fabric and history, and between the novel and a pantheon of Māori, Moana and anti-colonial thinkers and activists who have ‘loitered’ in literature, academia and urban spaces, partaking in the same resistance, feeling the same feelings, as Te Hoia and her friends. The symphony of bullshit spirals outwards, but so does the storytelling.

Turf War ends with a yellow sign taped to the bus shelter:

THIS BUS-STOP WILL BE TEMPORARILY CLOSED OR RELOCATED UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE

DUE TO DISRUPTION AND CAPACITY ISSUES, THE 23, 001 AND OVERPASS EXPRESS ROUTES WILL NO LONGER STOP HERE. PLEASE NOTE THE 365 BUS HAS BEEN DISCONTINUED

Is this the eponymous turf war over? Hardly. That’s not how a spiral works. Te Hoia may not “recognise her neighbourhood anymore … But there’s one thing [she] refuses to feel on her own land, and that’s lost”, she declares, before walking clumsily into the sun over the book’s horizon, off to find her own way through her city.

Auckland Transport might write you off the map, but literature remains a way to write yourself back in. It is also, Solid and Reilly remind us, a way to write against the grey, ministerial face that cities often offer up of themselves, communicating with their rigid language of timetables, parking tickets and eviction notices. The novel, by contrast, is a prism, one that not only casts its readers back and forth through time, yo-yo-like as Hardwick described, but refracts them at unexpected, distorting, illuminating angles. This all helps us to know our cities otherwise: their smells, falls of light, which sounds rise to the top of the racket, and the many lives that unfold next door to our own.

How To Loiter in a Turf War: A Novel

Coco Solid, PENGUIN $28

Greta & Valdin

Rebecca K Reilly, THWUP $35

–