Dec 6, 2017 Books

The kids were all right, whether thinning turnips or creating turmoil by going topless at Waiheke.

In Teenagers: The Rise of Youth Culture in New Zealand, he offers a corrective, charting the gradual emergence of a cohesive tribe. Many young people, he eloquently argues in the expansive and inclusive history, strained at the reins long before the 1950s — when they became an identifiable thing, with their milkshakes, motorbikes, and back-seat-at-the-movies heavy petting. “This was a century-long process of discipline and resistance,” he writes.

Take 13-year-old Mary Stephen as proof positive. In 1909, a 24-year-old sailor was caught fondling Mary somewhere in Wellington and was arrested. The unrepentant girl told the police: “I visit any warship I can get on … I go in a lot for physical culture and am well developed and I can box.” Jean McLeod of Wairarapa was equally as sassy, recording her response to her mother’s request to strip her bed in her diary in 1939: “Bake me.”

Brickell, an associate professor in gender studies at Otago University, largely turns his book over to his subjects. His sources are extensive and nicely pruned: there are newspaper articles, memoirs, oral histories, letters and photographs (“A colonial girl, Ruby Wilkinson Ophir, poses with her catch from the rabbit-infested Central Otago countryside one day in 1895”).

The book offers a chronological and highly sympathetic repositioning. Brickell commences with early settlers, taking in contact between Maori and Pakeha. In 1862, the Briton Charlie Brookes, aged 14, and his brothers were in the Kaipara: “At last we have got our land, and a beautiful place it is,” he wrote in a letter. “There are no less than a hundred varieties of ferns … it is a jolly life, an emigrant’s, to go through the beautiful woods and valley and we can say — ‘this is my own’.” Meanwhile, in Dunedin, at the Vauxhall Gardens, life seemed less innocent: adolescents played games called Whipping the Goose, Groping for Silver, and Catching the Cock.

Brickell tracks to the 1870s, when school, work, urbanisation and an expanding middle-class began to complicate the lives of young people, who began to divide along lines of subculture and class. There was the “masher”, an educated boy who worked as an office clerk, described by the Otago Witness as “an aesthete whose whole force goes to the worship of beauty, grace, and delicacy”. Then there was the working-class “larrikin” (if male) and “larrikiness” (if female) “yelling like fiends, and generally making themselves merry”, according to Wellington’s Evening Post.

The flappers arrived in the 1920s, all loose clothes and flirtation: “We are evolving into a race of tumultuous, tornado-like girls, whose hearts rebel against housewifery,” a young girl wrote to the Star newspaper.

Meanwhile, 13-year-old Hugh McMaster worked on his parents’ farm near Dunedin, recording in his diary: “Fine but cloudy. Went to creamery. Thinned turnips till dinnertime. Cut hay and ricked some today. Father and I set a dozen traps tonight and looked [at] them till about 9 o’clock. Caught two rabbits.”

The term “teenager” had already appeared in America during the Great Depression. It was a little slower to catch on in New Zealand, where at the time Margaret Stevenson was working in Wellington, having moved from Taumarunui: “What with the hard work and poor pay I still loved the city. It was so very different from what I had been used to. The crowds of people, the shops full of such beautiful things even if all I could do was feast my eyes on them. Riding on the tram-cars, having the conductors make eyes at you, wolf whistles from young carpenters on building sites … I was really living. I was growing up.”

World War II was in progress when a girl called Jean flashed on a mullet boat off Waiheke Island, as remembered by someone who egged her on: “And so it was that a dare was proposed. Yes! Jean would do it! … Under fore sail the gaff rigged yacht ghosted into Matiatia. The ferry had not long docked; yachts were at their moorings. People were boarding buses and a few cars. There, shock, horror, one of the girls was bare from the waist up! Fellow yachties cheered, old men gaped; children were enclosed in summer dresses lest their innocent eyes witness such depravity. The bay was in turmoil.”

Down in New Plymouth, 15-year-old Valda Tyson joined the ANA (Army, Navy and Airforce) club, which hosted servicemen on leave: “Us girls had a wonderful time as we had a fresh batch of keen young men every few months.” In Wellington, Mihipeka Edwards was likewise pretty happy: “The Yanks are beautiful dancers.”

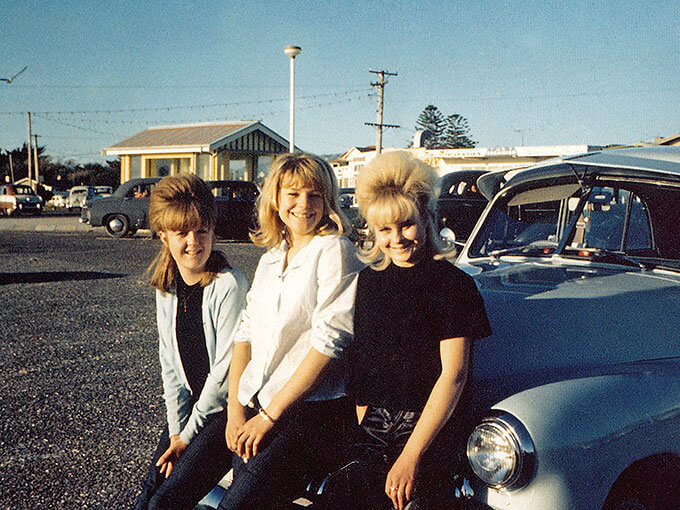

By the 50s and 60s, accelerated growth and prosperity fuelled teenage sub-cultures, and bodgies, milk-bar cowboys, widgies and Teddy boys were variously scaring the adults. Rosalind Warburton, a Whanganui fifth-former, wrote about a “tingling sensation that fills me when I drive the car — pride that I am alone the master of a forty horsepower engine”. And teenagers in Auckland went in droves to the Maori Community Centre in Freemans Bay, one frequenter remembering: “Maybe pick up a boyfriend, I dunno, all depends. But, that was far from my mind, we used to dance. Always had a live band [and] you could pick up a feed for 2/6 or 5 shillings. A boil up and a big cup of tea.”

Teenagers sign off proper in 1969, Brickell writing a brief chapter up to the present day. It’s a great read, but for those of us whose teenage years are long gone, also an elegiac one. Who wouldn’t want to be Sophie Tindall, in the 1950s, in Wellington, “riding on the back of a motorbike … doing 90 miles from the Basin Reserve right up Adelaide Road … sitting on the back, no helmet on or anything — saying ‘go faster, go faster’”.

Teenagers: The Rise of Youth Culture in New Zealand

Chris Brickell (Auckland University Press, $49.99)

This is published in the September- October 2017 issue of Metro.