Feb 2, 2024 Books

‘A Bloody Difficult Subject’, a new book by Bain Attwood about Ruth Ross, te Tiriti o Waitangi and history’s role in shaping Aotearoa New Zealand, intends an intervention: to wean us off our addiction to mythic pseudo-history. We might believe the Treaty’s purpose was to found our nation, but the truth is no one involved intended it to be the basis for our law or politics. And, though historians can help uncover what the Treaty originally meant, that meaning matters no more than all the other meanings and myths made about it ever since. Attwood encourages us to understand history is a messy business, not a morality play, and has a limited ability to sustain our democracy. I found ‘A Bloody Difficult Subject’ by turns fascinating, illuminating, impressive — and infuriating.

Calling on historians “to declare the moral and political investments they have in their subject matter”, Attwood reminds us that while born and raised here, he has based his distinguished academic career in Australia, one of too few — after savage cuts to the humanities there as here — still enjoying what he calls “the cloistered life of history”. So Attwood comes to his book “with a degree of distance”, as you can tell when hearing his Australian twang, which makes Waitangi, well, tangy.

His writing is salty too: Attwood is known for biting assessments, and has evident contempt for run-of-the-mill New Zealand historians. Other than fellow expatriates like John Pocock and Paul McHugh, or fellow iconoclasts Lyndsay Head or Mark Hickford, we appear insular, ignorant, provincial in our outlook and oblivious to the ways our history parallels that of so many other places. Across the wider world of empire, hundreds of treaties were signed between the British and indigenous peoples, and none of them are contended to have been meant to found nations. Many of our scholars, however, have been writing “mythic histories of the Treaty [that] have provided simple and one-dimensional accounts that have distorted the past”. Like so many New Zealanders looking back from overseas, Attwood seems keen to tell us how small-minded we seem to the wider world.

Those associated with the Waitangi Tribunal come in for especial disdain, so I should say at the outset that I, a Pākehā historian, have worked at the Tribunal, and at the Office of Treaty Settlements, later Te Arawhiti the Office for Māori Crown Relations. I was also involved in the Tribunal’s 2014 report He Whakaputanga me te Tiriti — The Declaration and The Treaty which found Māori had not intended to cede sovereignty to the British Crown. This is a text Attwood does not deign to mention. Unsurprising, then, that I found this a difficult book. But not, as might be assumed, because I disagreed with much of it. On the contrary, where Attwood writes as an historian, I agreed with almost all he has to say, if not always how he says it.

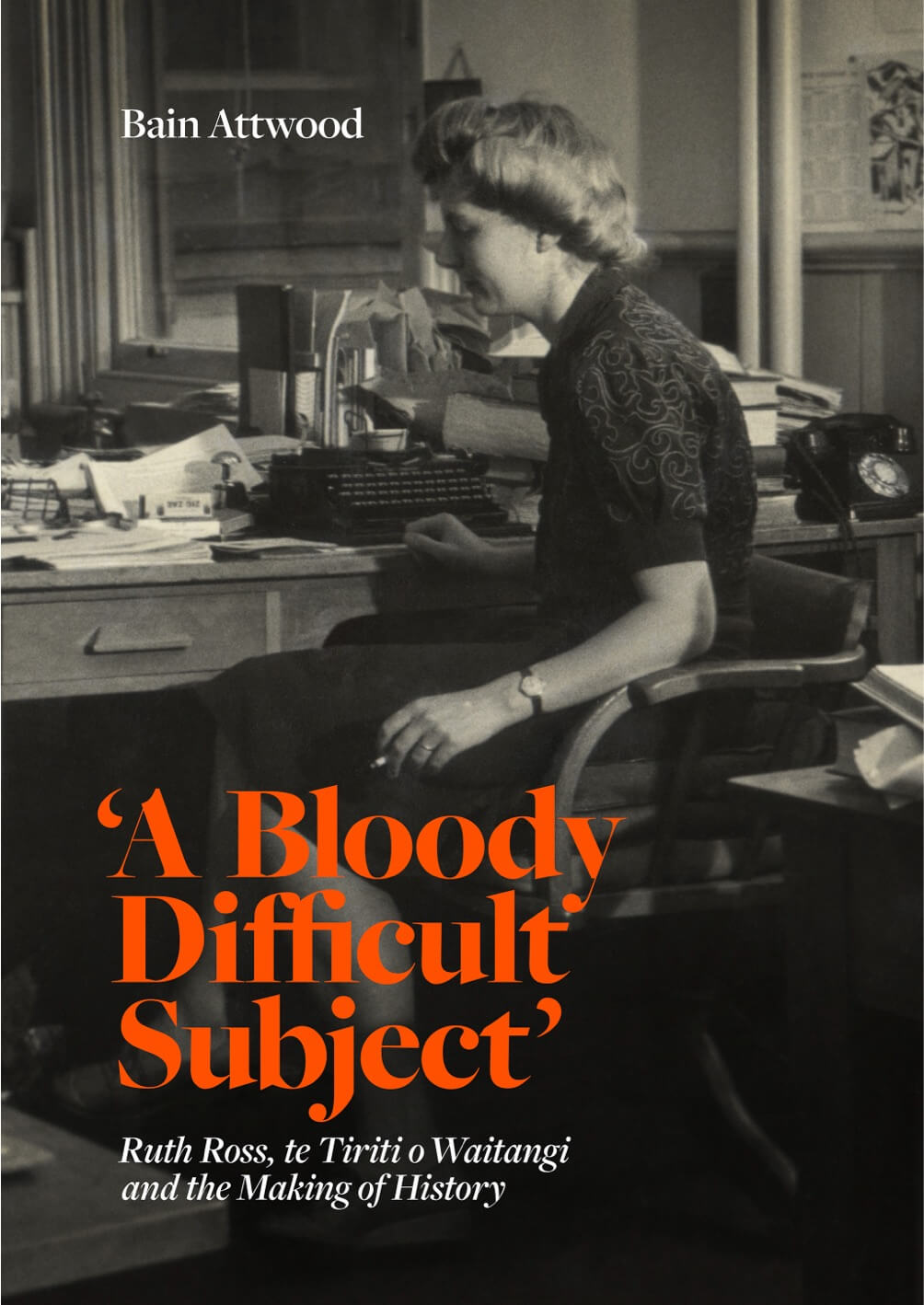

Attwood’s book opens with an excellent study of Ruth Ross and her writing on te Tiriti o Waitangi — as she insisted it should be named. Little known outside of a small circle of New Zealand historians and lawyers, her 1972 article in the New Zealand Journal of History is, in Attwood’s assessment, “one of the most influential pieces of work a New Zealand historian has ever written”. Attwood reveals it as the culmination of much of her life’s work, both in the archive, in earlier writing on te Tiriti and after years of dwelling in the Hokianga, where she came to know something of Ngāpuhi, whose tūpuna signed te Tiriti both at Waitangi and then at Mangungu, just down the road from where Ross lived a century later. Attwood’s sensitive and insightful portrait of Ross depicts her as a wife, widow and mother struggling to maintain a writing practice, crippled by self-doubt and insecurity, but also exacting, proud, determined to craft something of lasting worth.

Ross’s study of te Tiriti was stimulated by a commission from John Beaglehole in 1953 to write an introduction for the government’s publication of the Facsimiles of the Declaration of Independence and the Treaty of Waitangi. In her extensive archival work, she made two key discoveries. The first was the complete absence of an authoritative English version of te Tiriti — the official English version we have today is a late draft, possibly not even the last draft. The second was some of Hobson’s proclamations of sovereignty; that over the South Island was first made on the basis of discovery, before being amended after the Treaty signings.

The initial reception of Ross’s work in the mid-1950s was so scornful she retreated in dismay, giving up Beaglehole’s commission. Her article only emerged, years later, after the encouragement of Keith Sinclair, who succeeded Beaglehole as the country’s leading historian. Though Ross died in 1982, she lived to see her work becoming influential, but, Attwood argues, she would have been astonished by the ways her work was later reinterpreted.

In Attwood’s view, Ross’s major argument was that the Treaty signatories were “uncertain and divided in their understanding” of the meaning of te Tiriti. They could not be otherwise, given it was “hastily and inexpertly drawn up, ambiguous and contradictory in content, chaotic in its execution”. As a result, Ross argued, “[t]o persist in postulating that this was a ‘sacred compact’ is sheer hypocrisy”. In short, as she wrote to Keith Sinclair, “my only theory is that the whole exercise was a hopeless shambles”.

Under Eddie Durie’s charismatic leadership, the Waitangi Tribunal instead picked up her minor and auxiliary argument: that the only authoritative version of the Treaty was the Māori text, te Tiriti, since that was what Māori signed. For it was Ross who first emphasised the differences between the texts: among other things, between the cession of sovereignty, the agreement to kāwanatanga, and the guarantee of ‘te tino rangatiratanga’ to Māori against that of possession of their properties. These points are familiar to many New Zealanders now — though judging by their responses to the pop quizzes by the press at Waitangi, our politicians would benefit from studying the new history curriculum. When Ross was writing, they were fresh, new and compelling ideas.

A Bloody Difficult Subject

In Attwood’s telling, the Tribunal, historians such as Keith Sorrenson and Claudia Orange, and after them the courts, made a new myth of Ross’s argument: that te Tiriti was the Treaty, resurrecting it once more as “a solemn compact” that “signified a partnership between races”. Attwood argues that the “public life of history” here — the ways our past is debated in the public realm — has become unmoored from historical reality through constructing such “foundational histories”. Orange, he says, abandoned her principles as a historian: having revealed the Treaty had been seen very differently over time among and between Māori and Pākehā, she came to emphasise continuity instead, in order to present the Treaty as a legal agreement establishing rights. Similarly, Attwood’s review of Ned Fletcher’s recent tome The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi indicts it as “foundational history par excellence”, mythic rather than scholarly, providing an “egregiously incomplete account of the past” in a “remarkably turgid work”. While Fletcher’s book won this year’s Ockham prize for general non-fiction, to Bain even its publication was puzzling. In perhaps a sign of how far his editors have had to tone him down throughout, Attwood contents himself here with saying Fletcher has “broken no new ground”.

Attwood cannot always be saved from being cruel. At one point, he lashes the likes of Orange and Fletcher for being “astonishingly deaf to rhetoric”, by which he means historians ought always attend to how people use language to persuade, rather than taking their words at face value. Touché. However, his own shock therapy is not an especially persuasive way to intervene and shape debate. This prompts the question of who this book is for. Attwood complains key predecessors such as Lyndsay Head have been unfairly ignored (which is true). Should he suffer the same fate that would also be a great pity, but he has made it tempting to simply mock back, as Joanna Kidman has already done in a review titled ‘A bloody difficult historian’.

Attwood is on safer ground tracing how his favoured historians have already taken issue with this portrayal of the Treaty, and of the methods by which it was constructed. He provides incisive summaries of the work of Alan Ward, Andrew Sharp, Paul McHugh, Bill Oliver, John Pocock, Lyndsay Head, Michael Belgrave, Stuart Banner and Mark Hickford. Attwood acknowledges his debt to this illustrious roll call (notably all white and almost all men) in advocating “post-foundational history”. I think this an ugly term for sound historical method. Using it, as Attwood did in his 2020 book Empire and the Making of Native Title, predictably recapitulates much of what Ross had to say, finding the Treaty has only sometimes been significant, has always been contested, and has had contradictory and ambiguous meanings attributed to it even in its drafting, reception and signings.

Attwood’s provocative arguments deserve to be heard and widely debated. “The Treaty of Waitangi”, Ross wrote, “says whatever we want it to say”. Attwood reminds us this is not a bug, but a feature: it’s just the nature of how humans live in time. There may be only one past, but there are as many histories of it as people who care enough to tell and read them.

What, then, is the point of history? Attwood is happy to defend the position that “post-foundational histories can provide accounts of the Treaty that are truer to the past than any other histories” — but knows such histories may not be especially helpful to the life of our country and its community. How does history help us reckon with our past and shape our future? In his final chapter — perhaps the point of the book — Attwood turns to this question. Attwood’s acknowledgements that the Treaty involves matters beyond history, including ethics and justice, and that perhaps a nation needs a measure of myth, are welcome. However, precisely at this point, a historian steps outside their expertise; and while Attwood’s discussion is thoughtful and earnest, I found some notes off-putting.

Whenever Attwood writes about Māori, but especially in his final chapters, he does so only in ways that contrast them against Pākehā. In a book about the Treaty, perhaps it is unfair to expect interrogation of the ways hapū and iwi differ and disagree. All the same, I became uneasy that for Attwood ‘Māori’ are mainly an anthropological category. In his view, Māori are unwilling to be subject to historians’ methods, and instead “have been representing the past in ways that are dominated by subjective points of view and perspectives. They have been deliberately telling stories that often rest on a blend of history, the common law, oral tradition, myth and mātauranga Māori.” Attwood names no names here; indeed, virtually no Māori historians appear in this book, so no Māori scholars can defend themselves.

I thought straight away, though, of Sir Tipene O’Regan, Te Maire Tau, Atholl Anderson and Michael Stevens — four Ngāi Tahu scholars who are also (but not only) historians, and determined to protect the integrity of their traditions and culture, as when critiquing their spurious use in recent suggestions southern Māori reached Antarctica. Far from rejecting ‘Western’ history (or any of the sciences), they see their ultimate duty as being “to protect a rigorous and culturally inclusive scholarship”. They embrace history; they expect Pākehā to engage with whakapapa.

The debates at play between Māori and Pākehā about the meaning and role of history are as much contested within and across iwi too. Attwood concludes his book advocating for “sharing histories” rather than attempting to resolve them in one “shared history”; this seems to me resemble how Māori have long operated on the marae ātea: where visitors are welcomed, and the histories of hosts and guests, tangata whenua and manuhiri, debated without ever expecting an end.

This is a book that was written largely under Covid lockdown, meaning (among other things) Attwood could not do his own research here. Perhaps these circumstances added to Attwood’s distance, in more than one way. Attwood says he is not suggesting his perspective is superior, but I am not sure he really believes this. He certainly considers himself more objective, and his way of doing history truest to the past. But he cannot hear how foreign he now sounds to our ears.

‘A Bloody Difficult Subject’: Ruth Ross, te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Making of History

by Bain Attwood

Auckland University Press, $59.99