Dec 8, 2015 Books

Sexual dysfunction haunts Maurice Gee’s work.

Essay by Sue Orr

This article was first published in the September 2015 issue of Metro.

The weather wasn’t ideal for lurking; sleet needles, a vicious southerly shunting commuters homeward. An event at Wellington’s Unity Books usually attracts curious passers-by. They hover in the doorway, peek through the windows to see what’s cooking. Not on this night. You were either in or out.

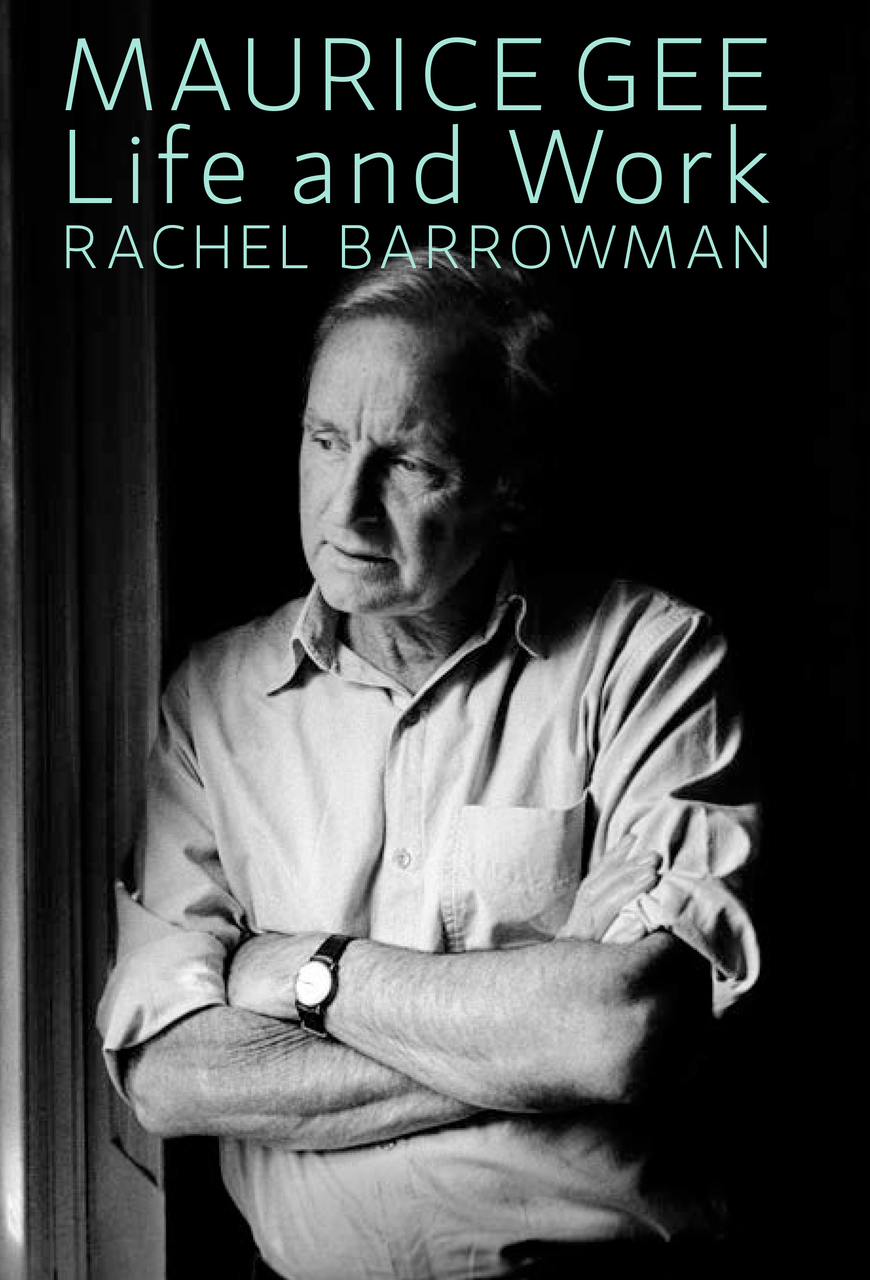

Everybody who was any-literary-body was in. It was July 9, the event was the launch of historian Rachel Barrowman’s long-awaited biography on New Zealand’s pre-eminent lurking, watching, listening writer, Maurice Gee. Nearly 10 years in the writing, the book promised to turn the tables on its subject, tell all his secrets.

Maurice Gee: Life and Work is a rarity — an authorised biography with no subject-strings attached. Gee simply told Barrowman to go and write it, before others less talented — less authorised — took it upon themselves to do so. Barrowman was already the author of an award-winning biography of Auckland poet and playwright R.A.K. Mason, and Gee trusted her. He gave her access to all his personal correspondence and papers; she had his permission to talk to whomever she wished. He even gave her a letter, which she could show to anyone who might be reluctant to break a confidence. It’s okay, the letter said, to say whatever you want. Put everything on the table.

And they did. The result — 543 handsomely produced pages — is an astonishing weaving of a prolific writing life with an intensely personal one. We blush at the awkward intimacy of what we’re reading. We blush, too, as it dawns on us that we’re being seduced. Barrowman does here what Gee does so famously in his adult novels: turns her readers into voyeurs, gorging on gossip, unable to look politely away.

It’s only when a biographer tackles the enormous, painstaking task of assembling the megadata — a lifetime of achievements, failures, thoughts and deeds — that we realise how much or how little we already know about the subject in question. In Gee’s case, it turns out to be the former. Barrowman’s finest achievement is the creation of a compelling narrative out of an already well-documented life.

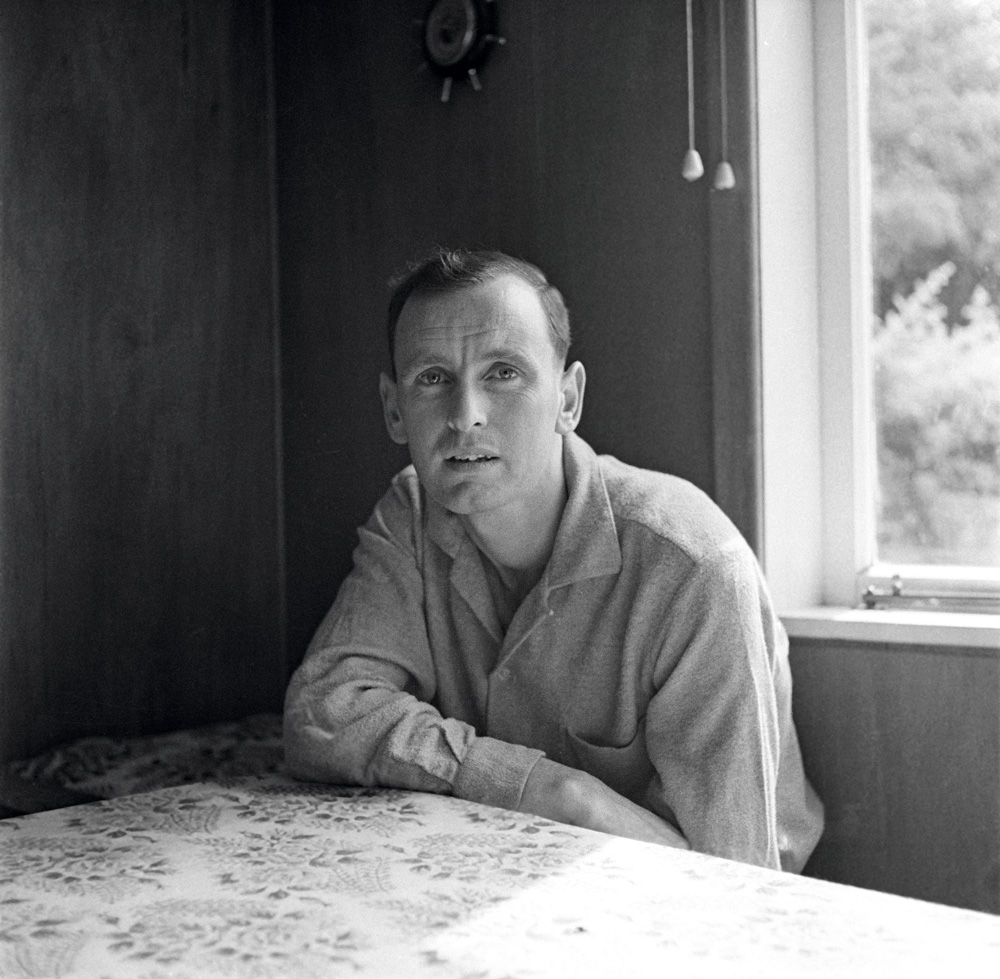

Gee’s reputation is one of shyness and a desire for privacy; a man in a grey cardie living a self-imposed quiet life. It’s true that he eschews public appearances. But, as Barrowman records, he has been generous over the decades in sharing his life story. The lengthy referencing of her source materials attests to that.

And then there are Gee’s own published writings, little pocketbooks and essays of clear-eyed, humble reflection on his relationship with family, community and the world. We know Gee’s Henderson creeks and their eels, the diving pool where, as a boy, he watched a man drown. The orchards and the kitchens where his beloved mother, Lyndahl, nurtured her three sons and quietly tried her own hand at writing.

Gee’s father, Len, the tough yet kind carpenter and ex-boxer, we know him too. And of course we know granddad, James Chapple, whose life inspired Gee’s most celebrated novel, Plumb.

It’s all there in the book, all in one place, finally. But Gee had more to share.

He wanted, he told Barrow-man at one of their meetings, to talk about sexual dysfunction. It had plagued his adolescence and young adulthood and, in a conversation that ended with Gee being “slightly weepy”, she says, he expressed relief that the matter was finally out in the open.

Critics and readers alike have puzzled and theorised over Gee’s frequent summoning of repressed sexuality and voyeurism in his fiction. Russell Haley, in a 1976 review of Games of Choice, described it as “obsessive interest”. In a 1990 interview with academic Colleen Reilly, Gee unpacked the voyeur motif to a certain extent, describing voyeurism as a “twin star” to self-exploration: self-exploring looking inward, voyeurism looking outwards, the process throwing up distortions that feed creativity.

But there was more to it than that. Gee hinted so in a North & South interview with Cate Brett in 1995, and again in a Listener interview with Steve Braunias in 2004. “I’ve got so many memories of my childhood, but when I get to my adolescence I switch off,” he told Braunias.

Now Gee has revealed to Barrowman that rampant childhood puritanism — fed by his mother’s refusal to discuss sexuality in any practical, useful way — left him in a state of almost constant sexual torment throughout his “swampy” adolescence.

As Barrowman worked through the archival material, she discovered that the problem didn’t disappear until Gee was in his thirties. He used medication and sought psychiatric help in a bid to alleviate sexual dysfunction, and he blamed the condition for derailing relationships and leaving him miserable. At one point, he received treatment at London’s Maudsley Hospital, where Janet Frame had been treated years earlier.

Barrowman is tactful in her descriptions of the impact on Gee, but echoes his own belief that it’s in the reading public’s interest to know about it. It influenced the person he became, and the nature of his writing, and — as Barrowman has pointed out — once you’re aware of it, you’ll find its shadow in many Gee characters. The trauma of sexual dysfunction is hiding in plain sight, right through Gee’s work.

One of the relationships tainted by the crippling puritanism legacy was formed in the 1950s with the late Hera Smith. She was to become the mother of Gee’s first child, Nigel, born in September 1959.

Gee was fiercely private about both Hera and the seven-year relationship, until Barrowman came along. He had been livid — mostly with himself — for disclosing information about it in a radio interview in 1995. Nine years later, in the Braunias interview, he would say only that the relationship “was a pretty bad time, for most of that time. Partly my fault, partly hers. I’m not prepared to say why or how.”

Barrowman says why, and how, and it’s a heartbreaking story. Both Gee and Smith had wanted a child, but there were no firm plans to stay together after the birth. It was, however, a relationship in which Smith called all the shots. This included where they would live (moving around the country) and giving Nigel up for adoption, a distressing decision on which Smith changed her mind, to Gee’s relief, at the last minute.

There was, in the middle of the period, a hoax call from Smith, claiming Nigel was dead. Most devastating, however, was Smith’s dis-appearance with the child in the mid-60s — it took Gee the rest of that decade to find him.

Gee told Barrowman that this sad time in his life might be squeezed into the biography. But both biographer and subject recognised it for what it was — a poignant yet devastatingly good story in its own right. It also had an eventual happy ending, for Nigel, his father, and Gee’s second family — wife Margareta and children Abigail and Emily.

Barrowman asked Gee to read the biography only once, when the final draft was complete. It must have been an anxious time for them both — she wondering whether he would lose his nerve; he stunned at both the scope and depth of what she had unearthed.

There’d been a whisper, in the lead-up to the launch, that Gee might be present. As the bookshop filled, I looked around for a certain man in a grey cardie. There were many, but not the one I wanted to see.

I’d wanted to watch him, secretly, examine his face, his body language as his life became public property once more. He was too smart for that, of course. But he did send Barrowman a letter, to be read out loud:

Reading Rachel’s book has been a strange experience for me. Seeing my life unroll again, or play as though on a screen, made me want to applaud myself for getting so much done, in work and relationships, and at other times had me squirming with embarrassment at my stupidities and shrinking with shame at cruelties and waste.

It’s all in the book. This is the biography I asked for when Rachel and I first spoke about it nine years ago. “Put in whatever you can find,” I said, not quite understanding that she’d find so much. But I don’t like biographies with holes in them. This one has no holes except for those Rachel has uncovered in her research and looked into with a clear eye. The research has been thorough, unrelenting, illuminating — illuminating even for me.

Did I really do those things? Yes, I did. And I had those two larger-than-life grandfathers, that saintly grandmother, that generous tough-guy father, that happy then sad, beautiful and gifted mother. I lived that energetic childhood and misshapen adolescence and young manhood, before coming to what I call my second life, with Margareta, my wonderful wife, with our daughters and my son — the writing life that they made possible.

Rachel has knitted the parts together with skill and patience. She has shown where the novels came from, surprising me with her insights. She has written it clearly and with style. I’m biased of course but I think this is a biography full of life, and a wonderfully readable book.

Thank you for it, Rachel, and thank you for giving me so much of your own writing life.

— Maurice Gee, July 2015.