Sep 22, 2014 Books

The problem with historic rape allegations is that they are hard to prove. There’s no physical evidence. He-said, she-said. Made more difficult, you’ll agree, when the victim says she screamed in her head and not aloud. And that she was pulled by force of personality and profession and not dragged kicking and screaming.

That is the situation the jury in the Louise Nicholas case faced as they decided the fate of then Assistant Police Commissioner Clint Rickards and former cops Brad Shipton and Bob Schollum.

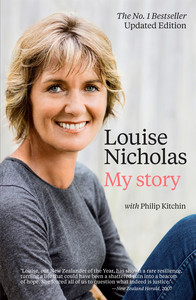

In her book Louise Nicholas: My Story, co-authored with journalist Philip Kitchin, Nicholas raises many of the issues that must have weighed on the jury. She didn’t scream, run away or fight back. And these men were police.

Not guilty on all 20 charges. The forewoman went through the list charge by charge. Nicholas felt like slapping her. The verdicts startled activists who had been distributing leaflets in defiance of court suppression orders. “Look!” they said, stabbing their fingers at their sheets of paper. The bastards have done it before. Indeed, Shipton and Schollum were already behind bars for the kidnapping and brutal rape of a young woman.

That made not guilty or guilty matter little, in many ways. There was something here that was bigger than the jury could see, but what exactly was it?

After the trial, the book recounts, the streets filled with protesters. Here was the real jury, the broad angry masses ignorant of all of the facts put before the jury, ignorant of the importance of not allowing previous convictions to be put before the court, but righteous in wanting these men punished and righteous for wanting a better system for dealing with sexual crime cases.

Something was wrong, but so were most of the solutions. Policy formation is not a suitable occupation for the baying masses and nor, in significant part, does it sit well in this book.

When policy ideas require us to discard principles of justice that have served us since the Enlightenment, they should be treated with caution. Encompassing Beccaria and Blackstone in the 1700s, it’s called the Enlightenment for a reason. It was the period when we went from intellectual barbarism to intellectual thought. A foundation of Western democracy and a slap in the face for religious faith.

Notwithstanding the thoughts of an upset crowd on Queen St, the fundamentals stemming from this period should not be discarded easily. Not that the Labour Party agrees. Justice spokesman Andrew Little has announced that the burden of proof should switch from innocent until proven guilty in sex-offence cases. In other words, the accused will have to prove consent. One might well ask how the hell you do that?

And in the deafening silence that follows, we find evidence that a moribund political campaign is as dangerous as the baying masses.

That’s not to say everything is right. It is far from right for victims of sexual violence, and this is where the book is important.

The statistics are startling. Research shows that perhaps as little as seven percent of sexual violence cases are reported to police, and only a fraction of those are brought to successful prosecution. Any person who doesn’t feel sorry about that is not thinking clearly, and the book personalises those statistics.

One of its strengths is that it weaves the whole story together so well. A fear that two authors (different chapters have either Nicholas’ or Kitchin’s perspectives) may make things disjointed is not realised. Presumably Kitchin played a big role here. The book reads seamlessly and the chapters link together like a novel. And for our baser instincts, the detail is disturbingly gripping.

If we are to believe the jury, the then 18-year-old Nicholas was not raped. But she was certainly abused — taken advantage of and bullied by older men who used her as a plaything. Rickards would later say they were things he “was not proud of”.

Nicholas’ descriptions of these events are vivid, conjuring images of heavyset men smiling, pounding, fawning, jostling to watch the baton painfully inserted in and out. Then discarding her: Get washed up, luv, you look a mess.

It’s easy to forget you are reading about the police. Our police.

But it was isolated to this rogue case, right? Wrong.

A commission of inquiry headed by Dame Margaret Bazley was established in the wake of allegations made by Nicholas and others. Bazley’s tiny physical stature holds the intellect of a textbook and the fearsomeness of a dogfight. Where Nicholas failed to scream, Bazley penned a report that bellowed. Loud enough to bring the walls down on a small but disturbing element of police culture.

The Bazley Report reviewed 313 complaints of sexual assault against 222 police officers between 1979 and 2005, of which 141 contained sufficient evidence to lay criminal charges or some other disciplinary action. Endemic? No, but numbers enough to make one uncomfortable. And not enough, according to Bazley, was being done.

The stories of Nicholas are harrowing. Her abuse, she writes, began when she was raped and sexually tormented by police officers in the small town of Murupara, from the age of 13.

While the veracity of these claims cannot be ascertained, a clearer and important function of My Story is to remind us that this is not simply a saga of sexual assaults. It is also one of police corruption.

The only person ever convicted in relation to any of the allegations made by Nicholas was John Dewar, the former detective chief inspector in charge of the Rotorua criminal investigation branch (CIB), who was found guilty of four charges of attempting to obstruct or defeat the course of justice. He was sentenced to four and a half years in prison.

Without the instincts and sleuthing of Kitchin, whose efforts cannot be overstated, Dewar would have gotten away with it too. And Rickards would almost certainly have become Commissioner of Police. It’s disturbing to ponder the impact his appointment might have had on police culture.

There was speculation that Rickards was going to take civil action again Nicholas. Perhaps realising that it was better to keep a shamed head down lest it might get taken clean off, Rickards instead pleaded publicly for a second chance. Everyone, he said, deserves one.

Nicholas has also moved on. Named New Zealander of the Year by the New Zealand Herald in 2007, she has since campaigned tirelessly on issues relating to sexual offending and the lot of victims.

We have much to thank her and Kitchin for. They gave us the Bazley investigation, all the while raising our consciousness around the issue of rape. A victim no more, Nicholas has the ear of, well, the entire country.

The police, too, have changed and undertaken numerous reforms to better handle sexual complaints. This will not be the last scandal they face, though. From time to time, people in any organisation will behave badly. We cannot expect our police to be perfect but we can demand that they react well when things do go wrong. In this case they did not, although Nicholas tells us that element of police culture is being fixed.

Things are changing, then, yet they are far from perfect. My Story has its own imperfections: in many parts you want both sides, just as the jury got. But this is not a book of balance; it’s one of outrage. An important outrage.

Louise Nicholas: My Story by Louise Nicholas with Philip Kitchin. Published by Random House, $39.95.