Nov 23, 2015 Books

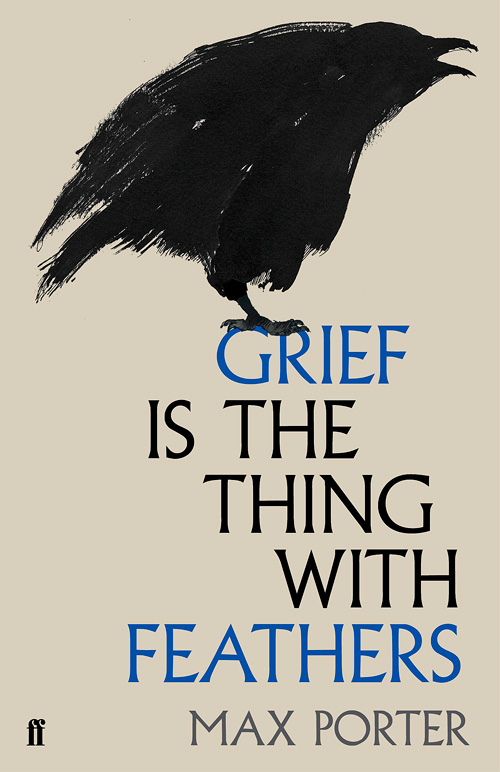

Grief Is the Thing With Feathers

Max Porter

(Faber, $39.95)

This article was first published in the November 2015 issue of Metro.

You could read this book in an evening and it would fuel you up for days. It has throat-catching sentences and achingly funny scenes. It is part fabulation, part novella, part grief treatise.

In a London flat, two boys face the unbearable sadness of their mother’s death and are visited by a crow, who decides to take up residence until he is no longer needed. The book charts the aftermath of the tragedy, except to use the word tragedy entirely misrepresents the brilliant and subversive nature of writing that is wise to fridge-magnet euphemisms and cliché.

Grief shifts and flutters, unhappiness ebbs and flows, and Max Porter writes beautiful compact sentences — words to fill your mouth, to size up the situation, that fit the scene, that lock everything into place.

Using short diaristic episodes from the lives of the boys, their dad, and the crow, the story circles the different stages of grief, how time moves on, how nobody moves on.

Porter has captured boyhood, fatherhood, grief, love and something like faith, in a compressed form.

The voice of Crow is a brilliant Russell Hoban-like invention; part-nanny, part-confessor, he relishes his role as “friend, excuse, deus ex machina, joke, symptom, figment, spectre, crutch, toy, phantom, gag, analyst and babysitter”. He is proud of his ability to “eat sorrow, un-birth secrets and have theatrical battles with language and God”.

When the book opens, the boys are young, with remote-controlled cars and ink stamp sets. They react to the news of their mother’s death with the perfect reasoning of their years: “Where are the fire engines? Where is the noise and clamour of an event like this? Where are the strangers going out of their way to help, screaming, flinging bits of emergency equipment to try and settle us and save us?” And then, “holiday and school became the same”.

Their biologically driven greed for life is set against the maudlin inaction of the sorrowing dad, a Ted Hughes scholar, whose work rubs off in the novel and who is “caught baffled by the perplexing slow release of sadness”.

Porter has captured boyhood, fatherhood, grief, love and something like faith, in a compressed form. Stories unspool from one-off sentences. It’s a slight book in length but, boy, does it give the heart a workout.