Apr 23, 2023 Books

Those of us who grew up in Tāmaki Makaurau generally have some relationship with or memory of the Auckland City Mission Te Tāpui Atawhai. Paused in Hobson St traffic on chilled Sunday evenings in the back seat of my parents’ car, I recall observing lines of people outside the sagging teal exterior of the Mission building, a 19th-century pub in a former life. The lines, literal breadlines, brought to my mind scenes largely derived from newspapers and television — the fall of the Soviet Union, New York City shelters and soup kitchens. Poverty, of all kinds, sits within a tension between enforced invisibility and plainly exposed humiliation, each corrosive for those suffering its effects.

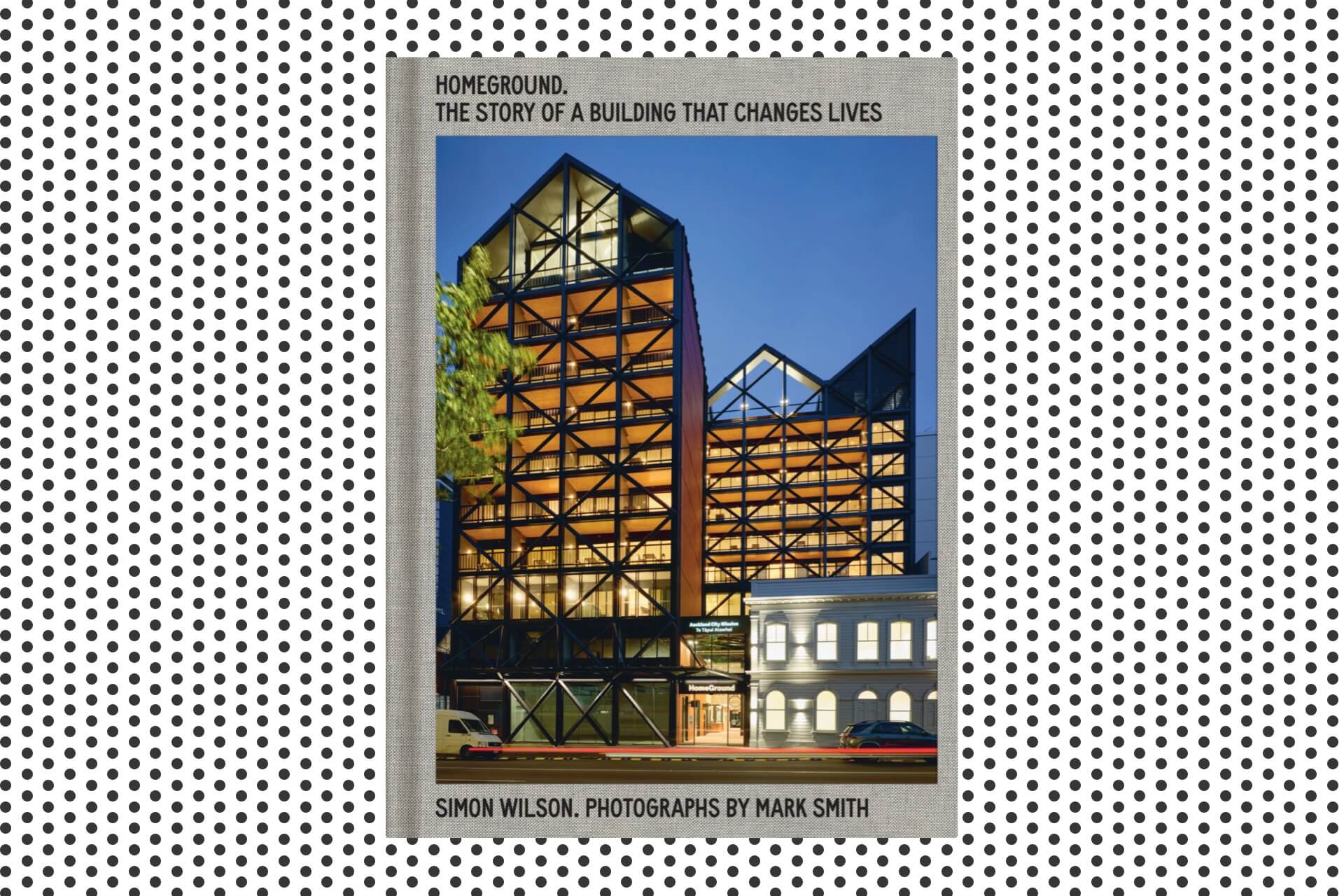

For over a century, the Mission has provided social services and support to those within inner-city Auckland. It was established in 1920 by the Rev Jasper Calder, prompted by the deleterious social effects of World War I and the Spanish flu epidemic. Now, Home- Ground, the redesigned Auckland City Mission by Stevens Lawson Architects, rises from the one-way artery of Hobson St, pressed between looming grey apartment blocks. Unassuming and elegant, the building sits adjacent to and behind its former incarnation, the Prince of Wales Hotel, built in 1882. The old building, now painted white, acts as a marker of the Mission’s origins. In stark contrast and not absent of metaphor, Home- Ground, fashioned in glass, terra-cotta brick, timber and black steel, ascends like a bird, its gabled roof resembling a wing lifting in flight.

What does a building owe its occupants and to what does a building owe its making? And how might a building exceed the limits of its own intentions? These are questions of justice and belief, and they are the loci around which journalist (and former Metro editor) Simon Wilson’s assured new book HomeGround: The Story of a Building That Changes Lives, is shaped.

After more than two decades of contemplation, research, planning, design, fundraising and construction, HomeGround opened its doors this year. The large-scale complex encompasses a singularly innovative approach to permanent residential accommodation and on-site wraparound social services. Wilson’s account of the build, from concept to inception, provides a sprawling and collective record of an institution that, essentially, resides at and represents the heart of this city.

The book charts the life of an idea: the redesign of the Mission to offer permanent housing (studio apartments that are home to 80 tenants); medical and social detox floors, including state-of-the-art addiction withdrawal facilities that amount to a secure hospital unit; various living spaces; and a cafe. A self-contained village, in other words. In words and photographs, the book functions as a living history of an institution alive to its own contradictions. The Mission is not its structural envelope — no inert building bound to orthodoxies nor helmed by those who see their work as done. It is the opposite, in fact: work of this nature is never complete, and it is the residents, occupants and all other people involved in its mission who ensure the institution remains alert to the needs of those under its shelter.

The choice to open the book with three introductory pieces underlines that HomeGround, the book and the wider Mission are all the work of many. A mihi by Mission kaumātua the Rev Otene Reweti (Ngāti Whātua, Ngāpuhi) references Jesus’s command in the Book of John: “If you love me, feed my sheep”. In his own foreword, chair of the HomeGround campaign Richard Didsbury lays out the “despair” of the city’s vulnerable and describes the Mission as the city’s “conscience, heart and hands”. Aucklanders have relied upon the Mission to care for our fellow citizens, he writes, “dealing with issues no one else wants to deal with”. The labour and results of the Mission have largely been unseen, he notes, but this new build represents a “visible manifestation of the Mission’s work”. It’s an interesting tension: religious orthodoxy does suggest charitable work ought not to reveal itself too loudly — it is a biblical command to give in secret — and helping in modest ways aligns with the national temperament to shroud one’s successes lest one be cut down to size. Yet work that goes under the radar also permits us to look away and leave others to ‘deal with the issues’. Wilson’s book seeks to counter these provisions of invisibility, positioning the Mission as a leading model, and one that deserves salutation, for combining ethics and aesthetics, government and corporate finance, community support and civic religion.

The Mission cannot be divorced from its Anglican origins and imperatives, and the new building therefore comes out of a particular theological context. Wilson’s own introduction takes its title, ‘Love is Patient, Love is Kind’, from Paul the Apostle. Paul’s letter to the Corinthians sought to answer and correct what he viewed as erroneous beliefs within the early church. As a convert to and disseminator of the teachings of Christ, Paul regarded love as self-sacrifice, as Jesus of Nazareth himself did. Saying that love is patient and kind these days risks a rather anaemic reception; but love is a verb, a doing word, and rectitude is a central tenet of what love does. “There can be no love without justice”, bell hooks writes in her 2000 book All About Love: New Visions. Hooks there undertakes to explore love, finding a meaningful definition in psychiatrist M Scott Peck’s classic self-help book, The Road Less Traveled. Peck interprets love as “the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth… love is an act of will — namely, both an intention and an action. Will also implies choice. We do not have to love. We choose to love.” It is a profound point when applied to the many loving people who made a choice prompting an action and together ensured the HomeGround building would come to pass.

Paul was incontrovertibly a militant, and in certain circles is understood as something of a proto-socialist in decrees and deportment. The disciple Luke recounts in his gospel that the early church — the body of believers assembled following Christ’s death — “were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had… from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need.” Centuries later, Karl Marx would elaborate on this by popularising the phrase central to progressive politics, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need”.

Similarly, Paul stated in 1 Corinthians that “just as a body, though one, has many parts, but all its many parts form one body, so it is with Christ”. This envisioning of the church as one body, unified in heart and mind, remains central to theological praxis. Following Pauline logic, then, a building may be a body but the people are its organs and so it is with HomeGround. It is sited close to and formally references the church of St Matthew-in-the-City, as well as embodying, as architect Nicholas Stevens identifies in the book, “the idea of the wharenui on the marae”.

The point here is twofold: the Mission is striving for an authentic Christianity and, irrespective of how the Anglican Church may feel about it (or socialists, for that matter), the services provided belong to the socialist tradition. Another tension the book and indeed the Mission reckons with is the history of colonisation, its continuing effects and the possibility of redress. According to a 2018 survey, a plurality (43%) of those living without shelter in Auckland are Māori. Te Tiriti o Waitangi is therefore an important force in HomeGround, as Wilson recounts the Mission’s objective to centralise, honour and effect Treaty partnership in intent and action. An apology issued by the chair paid some recourse to that history, as did the adoption of the name Te Tāpui Atawhai in 2021. Joanne Reidy (Ngāti Tamaterā, Ngāti Hako, Ngāti Raukawa), the manutea manager of Māori services, suggests about half of those who use the services are Māori, “and of them, over 50% don’t know their iwi. If you’re talking about people going home to reconnect, which is a good option for a lot of people, it might not be an option for them.” The stark discrepancies between Māori and Pākehā are clear in the book, offering a productive friction that is discomfiting to read at times — which is good; which is the point. In the context of colonisation and Treaty partnership, to consider love — central to both Christianity and the Mission’s project — is to consider power.

Wilson addresses this consideration by giving voice to many, decentralising his own perspective. Graham Tipene of Ngāti Whatua is one such voice. Tipene is a tā moko artist, designer and consultant to Stevens Lawson Architects and the man who sought out the mauri stone buried within HomeGround. Tipene describes apply- ing Te Aranga Māori design principles to the thinking behind the building and also drawing on Te Whare Tapa Whā, a model devised by Tā Mason Durie specifying that wellbeing has physical, spiritual, mental/emotional and familial/social aspects, as well as requiring the groundedness of whenua connections. Tipene says applying this model can mean “working with the wairua of a person, their spiritual sense… Sometimes people look at Māori values and assume they’re all warm and fuzzy”.

Not so much, Wilson adds. “Manaakitanga is about having hard conversations to get to easy ones.”

The book, like the build, reflects this manaakitanga: a collaborative effort over some 250 pages, replete with stunning photographs of the building and portraits of its pioneers, makers, staff and occupants by Mark Smith. In documenting the two-decades-long process of effecting a groundbreaking scheme, Wilson surveys not only the build itself but the impressive cast who ensured the project would manifest — some no longer at the Mission, some no longer living, each visionary in their own right. Their stories make for moving reading. Frequent leaps across time within chapters are occasionally disorienting but this helps to express the non-linear and complex task facing those early visionaries and, later, the team of architects, builders and project managers who, looking into the difficult and risky nature of the enterprise, continued on against stark odds.

It was previous missioner Sir Chris Farrelly who had wanted to better effect te Tiriti partnership and principles at the Mission. A former Catholic priest, Farrelly was recruited for the role of Auckland city missioner in 2015, and held the position until 2021. He describes the late Bishop Jim White, chair of the board from 2008 to 2020, as an “extraordinary man” who “broke the mould of what a bishop is perceived to be”. A photo in the book, taken from an odd angle suggesting a casual snap, reveals a modest Bishop Jim signing the $18 million contract with the government that enabled HomeGround to proceed. The build received bipartisan support and funding from successive governments which, Wilson writes, “demonstrates the value of a non-partisan approach to fundamental social issues … HomeGround is a beacon of humanism”.

The initiative is the first of its kind globally, Farrelly says, clarifying that the development was “part of an attempt to eliminate homelessness, rather than just manage it”. In its array of on-site facilities, HomeGround goes further than the Mission’s previous work. “We’re doing something special here, for the people among us greatest in need,” Farrelly tells Wilson. “The special thing the Mission has is its relationship with the people,” he continues. “They’re not just clients, or a statistic.” The planning team keenly understood “the influence and impact of the environment on behaviour”, and Farrelly now describes HomeGround as “beautiful and homely and not ostentatious”.

He had inherited the ambitious project from the previous missioner, Dame Diane Robertson, who, during her time from 1998 to 2015, instituted ‘A Mission in the City’ which took its cue from Common Ground (now Breaking Ground) in New York. Common Ground used the Housing First model to address chronic homelessness, advancing the idea that housing was the primary means to address addiction and other social issues leading to homelessness. Previously, you had to be clean to qualify for housing; changing this requirement led, eventually, to the wraparound services at HomeGround today. In 2006–07, a design competition for the venture was held, won by Stevens Lawson Architects in collaboration with fellow architect Rewi Thompson (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Raukawa) and mana whenua Ngāti Whātua. Wilson details the plans that were marked out, the funding in motion and then the halt that the global financial crisis put on proceedings.

In the intervening years, as new funding had to be found, the redesigned project became more and more innovative. Board members travelled to Common Ground facilities in Melbourne for research purposes. Farrelly worked with other social service providers including Lifewise and VisionWest, both of which were engaging with Housing First principles. A 2015 study by the University of Queensland which reviewed the efficacy of Brisbane Common Ground is credited with sharpening the Auckland group’s resolve. Comparative analysis revealed that the cost of leaving a person on the street for a year, taking into account judicial and medical services, totalled, on average, A$13,000 — more than it cost to house that person for the same duration of time. A similar report commissioned by the Committee for Auckland in 2008 had yielded similar findings.

As Wilson explains, the Mission plans were firming up at the same time Minister of Finance Bill English was pursuing his targeted ‘social investment’ approach to welfare. English was enthusiastic about what the Mission was proposing. Citing Celia Caughey, Mission deputy chair from 2011 to 2022, Wilson writes that English had been influenced by a 2013–14 research project by Robertson, ‘Family 100’, which interviewed regular users of the Mission food bank to examine what it was to live in poverty. “English used to carry around the ‘Family 100’ report in his pocket,” Wilson quotes Robertson as saying. “Celia Caughey says he was so impressed he wanted to know why Treasury wasn’t doing research like it.”

The sums required to achieve the project were enormous, and the means by which they were attained hugely complicated. Wilson entwines all these complex particulars to give a full, fascinating account of the funding. Foundation North, formerly ASB Community Trust, offered the largest single grant it had ever issued, $10 million. Successive governments supported the initiative with equal zeal, if not quite equal dollars. First, the National-led government contributed $18 million, 25% of the pie, under the watch of then Minister of Social Development Paula Bennett. In 2017, the incoming Labour-led government committed to the project and, with Labour’s 2017 election campaign oriented around alleviating poverty, Wilson writes, “the view that projects like HomeGround should be a state responsibility gathered force”. At the petitioning of the committee, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced in 2018 an extra $16.7 million for the detox floor, financed through the Proceeds of Crime Fund.

Wilson details the intricacies and sensitivities of procuring capital in a chapter titled ‘The Politics of Giving’. There, Richard Didsbury notes that giving to the Mission is different to philanthropy offered to organisations like Auckland Art Gallery where a donor’s name might appear appealingly on the wall. HomeGround eschews this practice; it is “true philanthropy”, Didsbury says. “The donors are anonymous and there’s no honour roll.” As chair of the campaign group, and himself a philanthropist, property investor and developer, Didsbury delivers shrewd business acumen with levity. No stranger to the high-end, high-net-worth constituency, he shares candid insights into the politics of network- ing. Some rejections surprised Didsbury, Wilson writes. One “very high net worth” individual, “very generous

to other charities”, told Didsbury it was not the private sector’s obligation, that he wouldn’t contribute for the fact it made a “compelling case for central government”. Didsbury also recounted the change in tax policy in 2018 that targeted high earners: “I’m rattling the bloody tin and all my mates are saying, ‘Hey, Richard, you don’t need me, the prime minister is going to write the cheque for you’.” Didsbury didn’t, Wilson adds, entirely disagree. When Covid-19 hit, the building costs ballooned but the campaign was able to draw on the ‘shovel-ready’ infrastructure fund, ratified in mid-2020. All up, the government contributed around $58.8 million to HomeGround and the private sector $56.2 million, including $8 million in Mission-donated funds.

In response to this support from all sectors of society, Helen Robinson, the current manutaki missioner, describes the organisation not as the Auckland City Mission, but “Auckland’s City Mission”. Caughey tells Wilson they approached funders from the perspective that “we each have a responsibility to create the sort of society we want to live in”, and HomeGround the book functions as both a tribute to this past work of creation and an illuminant for the future. Its stated objective is to increase the number of similar builds across the country.

The heart and centrepiece of the book is the chapter entitled ‘Ngā Tangata, the Tenants’. Wilson here records an organic and dynamic conversation between Ivan Tepu (Ngāti Rereahu) and Lisa-Marie Peerdemen (Ngāpuhi), two of the tenants residing within the apartment complex. Wilson mostly removes his own voice from this section, centring the pair and their respective stories. These are a damning mirror held up to a society — our society — that permits inimical deprivation, poverty, abuse and lives afflicted by an unmitigated and overwhelming sense of lack. The stories would be familiar as a news item — childhoods marked by poverty, upheaval and disconnection from their whenua and language — yet Tepu and Peerdemen are not reduced to cursory statistics, and they do not suffer that most deleterious result of injustice, poverty of spirit. To the contrary, the pair seem to have the disposition unique to those who have suffered greatly, oscillating between a half-eyed wariness and unequivocal yielding to the truth of how things were and are; a blunt acceptance of the past and the people they have become. They share this acceptance unreservedly. “You know what?” Peerde- men remarks, closing the chapter, “You just got to love yourself. And forgive what’s happened, eh?”

Also warm is the conversation between architects that unfolds over a chapter. Nicholas Stevens and Gary Lawson of Stevens Lawson describe their ambitious push to secure the job and the transformations the original concept took in the years that followed. The ground-level laneway that runs between Hobson and Federal Sts is described as the “organising spine” of the building, coupling interior with exterior. The evolving relationships depicted in this book are a different type of spine. While drawing out individual contributors to the project, Wilson finds a common theme: a purposefully humanist commitment, one that wanted dignity for those who would find home within HomeGround’s walls. Stevens refers to himself as “a bit of an old socialist”, and while Stevens Lawson is known for its high-end and high-priced designs, the architects here were keen to engage in civic-oriented work. HomeGround is, Stevens says, “what architecture should be doing… There didn’t seem like there was a project as crucial as this, in terms of what you can do for people.” Lawson adds that those on the margins are “on the fringes in every way. The laneway is an attempt to unpack that.” The pair understood the scale and sense of the Mission’s vision, Celia Caughey says. “The fact that we wanted a home, not a commercial building.”

This position echoes a distinction made by the late Moana Jackson (Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Porou) between the unhoused and the unhomed. In ‘Mountains, Dreams, Earth and Love’, an essay in the just-released book Kāinga Tahi, Kāinga Rua: Māori Housing Realities and Aspirations, Jackson evaluates “the violence of colonisation internalised within the vio- lence of neoliberalism” and presents home as a “concept of place, a concept of belonging, a concept of being… one of the difficulties we have in the area of homeless- ness in this country is that we haven’t yet clarified what it means to be at home in this land”. Similar themes appear in the aspirations of Matike Mai Aotearoa, the independent working group on constitutional transformation for which Jackson was convenor, which sought a “Treaty-based society” and constitutional order for New Zealand. The Treaty, Jackson believed, offers “a shared sense of home… [where] not only will everyone be housed, they will be homed in this place”.

HomeGround is bookended by a dense and thoughtful essay that offers an analytical and philosophical account of the building, ‘An Architecture of Place’, by Professor Deidre Brown (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu) and Pacific academic Dr Karamia Müller of the University of Auckland’s School of Architecture. Their appraisal takes the reader through the building by considering both

its materiality and metaphysics. The text is rigorous, melodious and methodically rendered, reflecting the calming wairua of the complex. Addressing homelessness through architecture, they write, “requires thinking beyond housing as shelter; it is instead the creation of spaces intertwined with concepts of belonging that fosters connectedness and a community grounded in place”. The ambition for HomeGround, they submit, is one of “systematic change and transformational change for those experiencing homelessness… accomplished by imagining the building as an integrated ecosystem… not just in the large number of residential units or the wide scope of the wraparound services — but also in expansive thinking”.

Closing the book with this essay further emphasises that the building and therefore the book belong to many, and are polyphonic in genesis and in form. There are, however, minor criticisms that could be made of the book. Wilson at times blurs reportage with editorialising, or paraphrases what has been said by a subject as though translating for the reader. He offers well-constructed scenes that do the job intended, and these do not always need the sentence or two tacked on to guide (if not direct) the reader about how to feel about them. This extra guidance has the effect of corralling one’s already empathetic response into sentiment, when no such persuasion is required. An edge of sentimentality does appear at points throughout the book — certainly a risk when addressing issues of people’s welfare.

Living unhoused is foremost a materialist concern, so how then to adjudicate the role of aesthetics? The way this issue is tackled in the book is analogous to visiting the complex and finding oneself next to a Martino Gamper Arnold Circus Stool — a ubiquitous signifier of class (if not one of a certain heuristic for taste) that graces bourgeois homes. Or wandering up to the rooftop garden (a remarkable feature of HomeGround, with equally remarkable views) and wondering whether you have arrived at a boutique hotel. This is a central tension for the book itself. Who is it aimed at? It is a beautifully designed coffee-table book, a somewhat hefty tome, and therefore may function as a conversation prompt in the living rooms of Grey Lynn. A more charitable reading would say it is a book designed with the beauty and care its subjects deserve. Indeed, the ethos of HomeGround is expressed in the design of the book through its materials — the rough fabric cladding of the cover, inset with a glossy photograph of the complex, hints at a leitmotif of the book: “shaping hardness with gentleness”.

The tension is dissipated, however, by the honest, forceful, unmediated voices of those who worked for decades to make this building. Through them, Wilson crafts an analysis of love as a material force for justice in the world, saving it from cynicism or naive idealism. Among the many other impressive figures through-out — terrific exemplars of the precept that to teach is to demonstrate — Farrelly emerges as a particularly admirable leader. See, for example, his decision to retire in April 2021, ceding the manutaki role to Helen Robinson. Farrelly told Wilson that he wanted his replacement to inaugurate the building: “Not me. I didn’t want the old way of doing things — you stay and cut the ribbon.” Robinson herself says that the building “should not have happened. There was not the money, not the time, any which way you look at it.”

If, as Robinson believes, the Mission belongs to Auckland, then the book’s greatest achievement may be its unremitting reminder of our communal obligation to one another. It is certainly a remarkable accomplishment for Wilson. He has woven a decades-long and intricate story into an adroit narrative, relating the social, political, environmental and architectural issues with much elegance. And his ear for a distinct line and the flavours of speech elevates each interview, offering immediacy and making the reader feel like they’re present to the conversation at hand.

The sheer scale of the project, and the devotion and commitment each figure maintained over the decades, make a lasting impression on the reader. The book depicts a project riddled with discontinuities, afflicted by circuitous events and plagued by circumstances beyond the Mission’s control. All these roller-coasters and cliff-hangers beget emotional investment in the reader. It is assuredly important to have a public record of what the people of this city helped to build, and even more so to have a document pointing us towards further action on the horizon of possibility. Wilson believes that HomeGround is a building that transforms lives. HomeGround the book may very well foster such change in the reader, too.

HomeGround: The Story of a Building That Changes Lives

by Simon Wilson, photography by Mark Smith

Massey University Press

$65

–